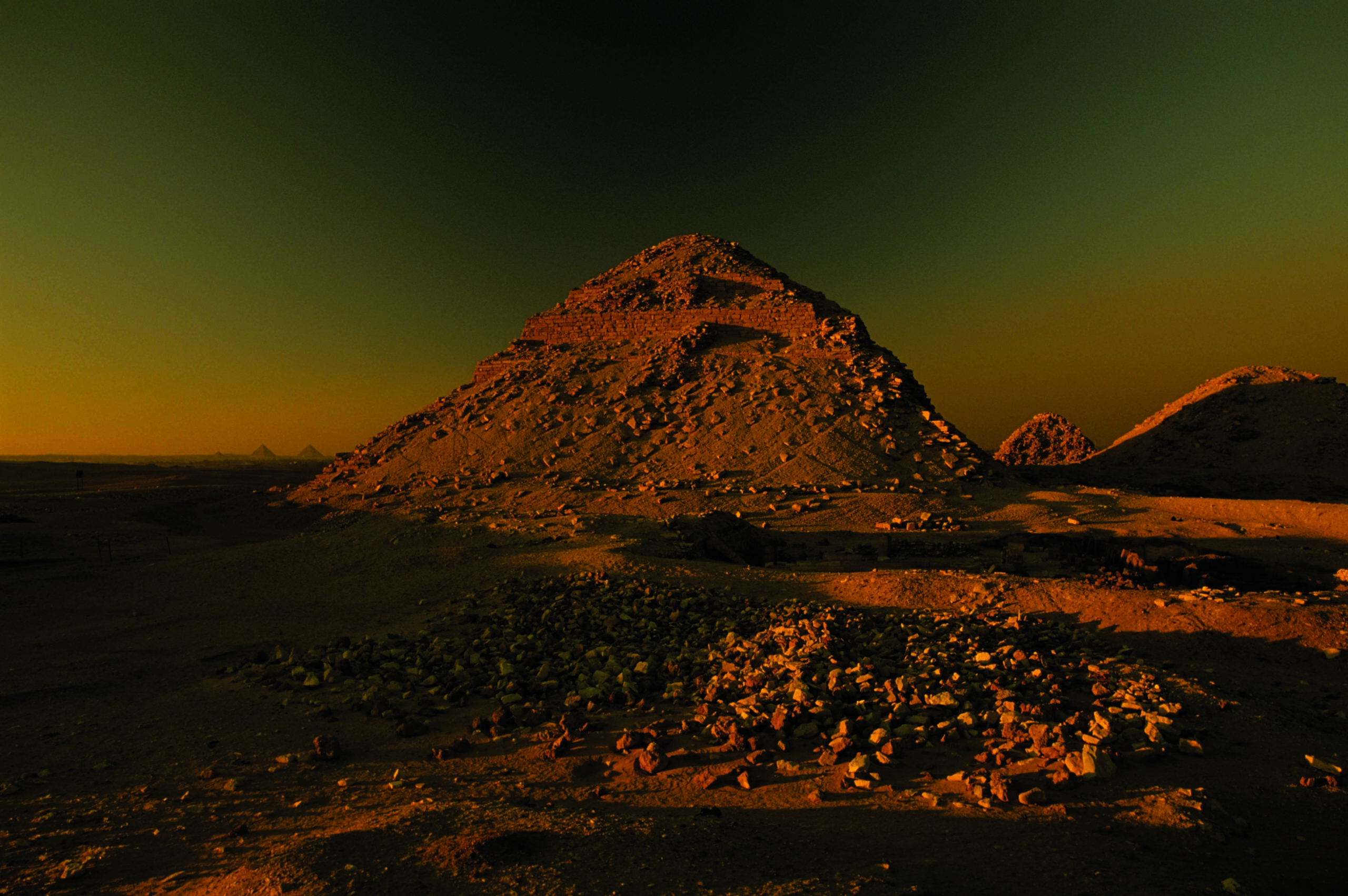

One of Egypt’s great vistas, says archaeologist Miroslav Bárta, is the view from the top of the pyramid of the 5th Dynasty pharaoh Neferirkare in the necropolis of Abusir. On a clear day, you can see all the iconic monuments of Egypt’s Old Kingdom from there. Ten miles to the north are the Great Pyramids of Giza. To the south rise the Bent Pyramid at Dashur and the great pyramid complex of Djoser in the nearby necropolis of Saqqara. This majestic tableau on the Nile’s west bank is the most visible legacy of the Old Kingdom pharaohs of the 3rd through 6th Dynasties, who reigned from about 2649 to 2150 B.C. and were celebrated throughout Egyptian history. The monarchs of the 3rd and 4th Dynasties oversaw the creation of the country’s most massive pyramids and loomed large in the Egyptian historical imagination. But Bárta, head of the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Abusir Mission, says that the true legacy of the Old Kingdom lies in the momentous social changes that occurred during the reign of the 5th Dynasty pharaohs. Their relatively modest pyramids in the necropolis of Abusir may be somewhat overlooked by tour groups today, but the discoveries made by Czech teams there since the 1960s have shown how radical changes instituted during the 5th Dynasty irrevocably impacted the trajectory of Egyptian history. “Abusir tells the story of a time when Egypt changed utterly,” says Bárta.

First built during the 3rd Dynasty near the newly established capital of Memphis, pyramids were symbols of the pharaohs’ unrivaled ability to command vast resources and labor. At least initially, the pyramid-building projects also seem to have contributed to an increasingly sophisticated bureaucracy and the spread of resources throughout the kingdom. “During the construction of the Great Pyramid, I would say that perhaps a quarter of the whole population profited from this single project,” says Bárta. By the end of the 4th Dynasty, though, these incredibly expensive royal constructions came close to bankrupting Egypt. The pharaohs of the 5th Dynasty not only inherited a precarious financial and political situation from their predecessors, whose profligate tastes in mortuary practices may have soured large segments of the Egyptian populace on the entire concept of royalty, they also came to power during a period when the climate was becoming increasing unstable. Decreased rainfall seems to have led to droughts, and the subsequent poor harvests threatened both the country’s prosperity and the royal tax revenue, which would have made the pharaohs’ hold on absolute power tenuous. The model that had held sway during earlier dynasties—that of power being invested in a single royal family—was not adequate to the challenges the 5th Dynasty pharaohs faced when they inherited the task of running an increasingly complex government. Suddenly, they found themselves compelled to share authority with a new class of non-royal officials.

The necropolis of Abusir was the domain of most of the 5th Dynasty pyramids, but it is also densely packed with hundreds of other funeral monuments, including large rectangular tombs known as mastabas that held the remains of non-royal elites and testify to the growing social and political clout of this newly influential group, whose ranks included important priests and scribes. “It’s a story familiar to us today,” says Bárta. “A few families grew powerful and began to control more and more resources.” This new breed of official made their standing clear by commissioning lavish tombs close to those of the pharaohs. “There was a race for status,” says Bárta, one that included the pharaohs themselves, who had to find novel ways to compete with their newly potent subjects.

Recent discoveries made by Bárta’s team in Abusir and nearby Saqqara are providing a new look at this period, when a radical shift in political organization transformed the face of the Egyptian monarchy. It was also a time that witnessed an efflorescence of new styles of art and saw the rise of the cult of Osiris, the god of the dead. The 5th Dynasty pharaohs closely identified themselves with the sun god Ra, and controlled worship of the deity. But veneration of Osiris was not overseen by the pharaohs and was available to all who worshipped the god in the proper manner. Osiris ruled over a netherworld that contained not just the pharaoh’s soul, but the souls of all Egyptians. “We can call this a process of ‘democratization’ or widening participation in sacred affairs,” says Bárta. “It was a new way to balance power.”

The kings of the 5th Dynasty were not the first to retrench from their predecessors’ extravagant mortuary practices. This pattern had played out during the 2nd Dynasty, too. The pharaohs of the 1st Dynasty were buried in tombs in the necropolis of Abydos along with hundreds of sacrificial burials. But the practice of killing great numbers of citizens evidently became a burden on society, and the 2nd Dynasty pharaohs were buried along with fewer and fewer people. By the dynasty’s end, the number of sacrificial victims accompanying their rulers to the underworld had dwindled to zero. It may have been that in the face of popular resistance, the pharaohs curtailed the practice. Even during the 4th Dynasty, the immense stress pyramid building must have placed on the royal treasury began to show. The last pharaoh of the 4th Dynasty chose not to build a pyramid, but was instead buried in a mastaba in Saqqara. This was a considerable downgrade from the Great Pyramid at Giza, which still towers 455 feet above the Nile Valley. By the time the 5th Dynasty began, around 2465 B.C., there must have been general agreement that such ambitious building projects were beyond the pharaoh’s means. The 5th Dynasty pharaohs built significantly smaller pyramids than their predecessors, first in Saqqara and then in Abusir, which freed up resources to construct increasingly sophisticated and richly decorated mortuary temples adjacent to their royal temples.

The dynasty’s founder, Userkaf (r. ca. 2465–2458 B.C.), also instituted the practice of building solar temples, elaborate complexes centered around obelisks. These were dedicated to Ra and linked the pharaoh’s authority to the sun god’s supremacy. And there is some evidence in later texts that the 5th Dynasty pharaohs had good reason to cement their legitimacy. A Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) document known as the Westcar Papyrus suggests the 5th Dynasty rulers may have come at least in part from non-royal origins, making them keen to prove their bona fides as deities on Earth. The story recounted in this document is that the first two 5th Dynasty pharaohs, Userkaf and Sahure (r. ca. 2458–2446 B.C.) were sons of the god Ra. Because their royal lineage isn’t mentioned, some scholars have inferred they were not of royal stock, which would have made their connection to Ra even more important in asserting their powers as gods on Earth. All the kings of the 5th Dynasty but one took regnal names that linked their power to Ra, testifying to their special connection to the god of the sun.

A total of six solar temples were built during the 5th Dynasty. Offerings for all the royal mortuary complexes were first taken to these temples, where they were “solarized,” or exposed to the sun for a set period of time to absorb its power. The sun temple of the 5th Dynasty pharaoh Niuserre (r. ca. 2420–2389 B.C.) lies just north of the necropolis of Abusir and had extensive storage facilities for these sacred gifts, which could include everything from food to furniture. “Rich and varied offerings flowed from the residence of the king to the solar temples and from there to individual mortuary temples where, after they were symbolically offered on altars, they were used as payments in kind to different ranks of officials,” says Bárta. “In a situation when more and more non-royal officials started to occupy even the highest positions in the state administration, this enabled the king to maintain some control of the country’s resources.”

During the 3rd and 4th Dynasties, political power in Egypt had been centralized in Memphis in the person of the pharaoh and his family members. But from the beginning of the 5th Dynasty, high-, mid-, and even low-level officials seem to have been granted unprecedented levels of authority and income. By the reign of Niuserre, an official named Ty, whose titles included King’s Hairdresser, was buried in a monumental, multiroom, richly decorated complex in Saqqara that was first excavated in the late nineteenth century. Large reliefs in the tomb depict at least 1,800 people, mainly priests, but also farmers, hunters, and other common people going about their daily life and providing services to Ty and his family. The tomb embodies the social changes that were accelerating during Niuserre’s reign. Expensive non-royal tombs and the appearance of family tombs at Abusir during this period show that new networks of power, likened by Bárta to those of nepotistic organized crime families, were beginning to compete with royal authority.

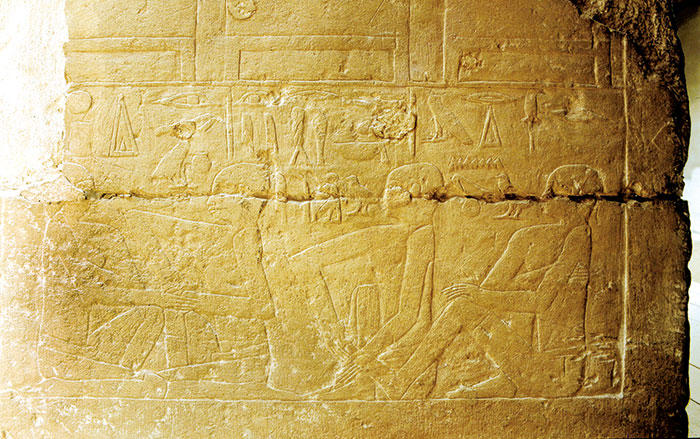

The reign of Niuserre was also the period when Osiris, the lord of the netherworld, was mentioned for the first time. Hieroglyphic inscriptions praising the god have been discovered in the tombs of officials in Abusir and Saqqara. He was first invoked as an important deity in texts discovered in a tomb at Saqqara belonging to an official named Ptahshepses, who served Userkaf and died during the reign of Niuserre. The official’s son, also named Ptahshepses, was Niuserre’s son-in-law. The younger man’s many titles included Privy to the Secret of the House of Morning and Overseer of All Works of the King. He seems to have been the first vizier whose power came close to equaling that of the pharaoh, and his many functions and titles were passed on to his descendants. In fact, his funerary monument in Abusir was more spectacular than the tombs of members of the royal family and rose in pride of place in front of the pyramids of Sahure and Niuserre. No hieroglyphs have been discovered in the tomb of the younger Ptahshepses acclaiming Osiris as the king of the dead, but it is likely that, just as his father had been, he was loyal not only to the pharaoh on Earth, but to the pharaoh in the next world as well.

A host of smaller, but nonetheless dramatic, monuments in Abusir and Saqqara also chart the changes that transformed Egypt during the 5th Dynasty. “These are kind of time capsules,” says Bárta. “They are badly known and poorly explored entities in Abusir and Saqqara that are, however, of significance in filling in our knowledge of this critical era in Egypt’s history.” Bárta’s colleague Veronika Dulikova has conducted extensive analysis of the names and titles of officials buried in the cemeteries. This has enabled her to partially reconstruct a complicated network of family ties that kept the 5th Dynasty government functioning. These families constituted what Bárta only half-jokingly refers to as “the world’s first deep state.”

The Czech Mission has recently excavated tombs belonging to one of these powerful extended families in a cemetery at Abusir founded by the chief royal physician Shepseskafankh, who served the pharaoh Neferirkare. Inscriptions in the cemetery show that in many cases successive generations of the family held the same titles. “We can follow a strong tendency towards nepotism during a period when important offices were controlled by the same families,” says Bárta.

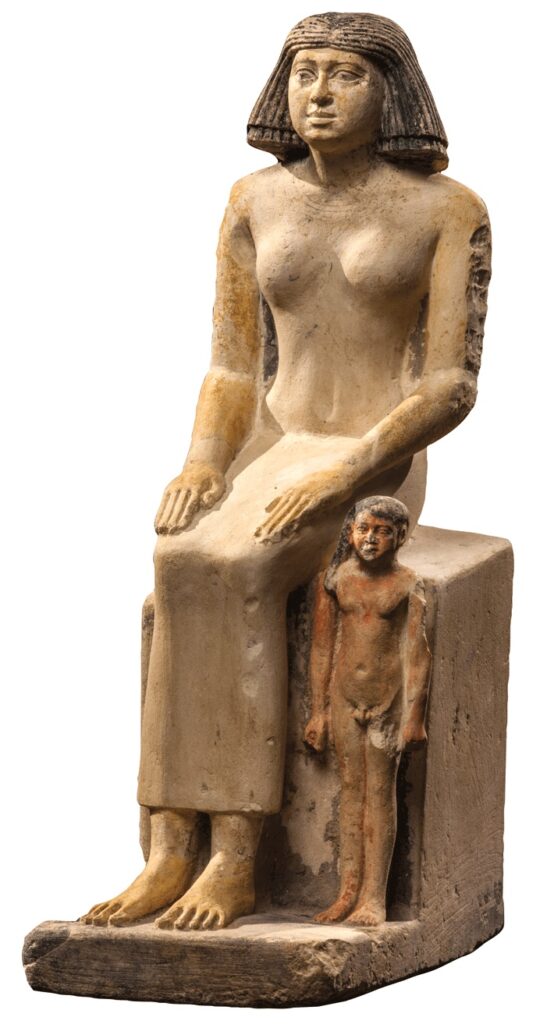

In 2012, his team unearthed the rock-cut tomb complex of Niuserre’s daughter Sheretnebty in the Shepseskafankh cemetery. They were surprised to find the tomb of a princess located so far from her father’s pyramid, where her sisters were buried. Instead, her tomb was built next to that of her husband, an important non-royal official whose name is lost, but who must have been related to the Shepseskafankh family. Inside the tomb, the team discovered limestone statues of Sheretnebty and her husband, along with his elegantly crafted limestone sarcophagus. Bárta notes that despite the man’s evident influence, men of his station rarely married members of the royal family. “This shows that the king used the marriages of his daughters as a means of controlling the rising independence of powerful families,” he says.

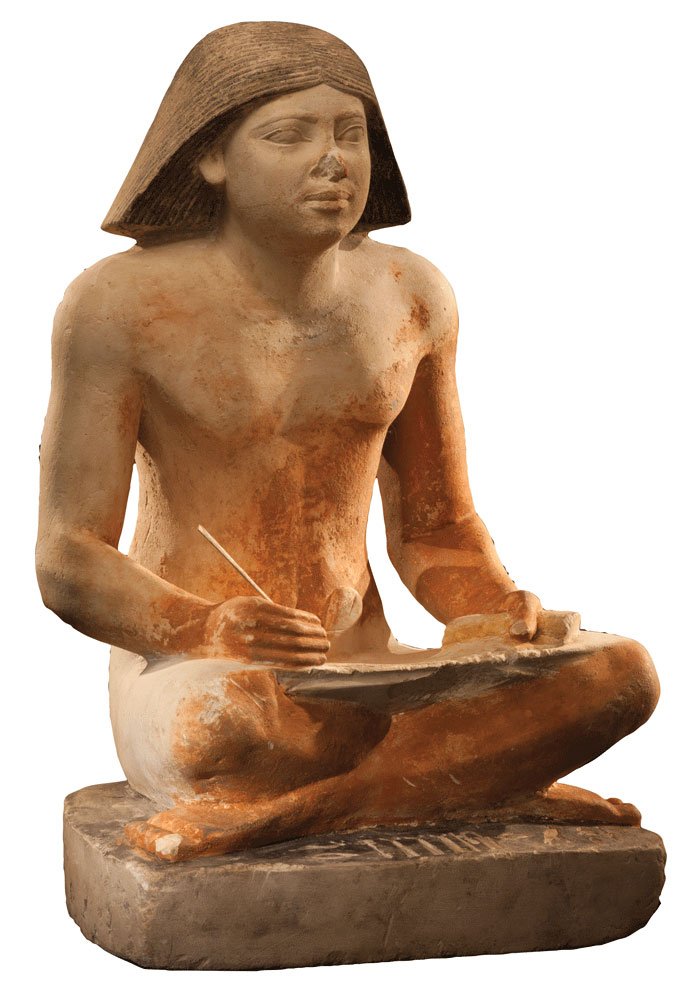

Another large tomb in the cemetery recently unearthed by the Czech team belonged to Kairsu, a powerful scribe who served under Niuserre. His tomb was built just north of Neferirkare’s pyramid and featured dark basalt blocks in its facade and in an adjacent chapel. This particular material was typically used in royal tombs, and Kairsu’s monument is thus far the only instance of an Old Kingdom non-royal tomb outfitted with these blocks. They may have been intended to serve as metaphors for the rich soil in the Nile Delta, where, according to myth, Osiris was miraculously reborn.

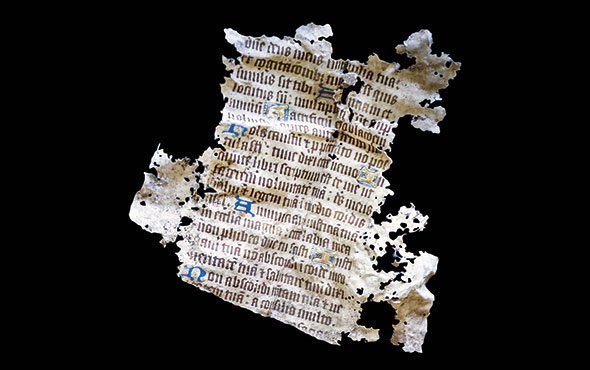

Bárta and his team also unearthed a statue of Kairsu in front of his sarcophagus. This confirmed a long-held, but never proven, assumption that Old Kingdom officials set up statues of themselves in their burial chambers. Inscriptions in the tomb show that one of Kairsu’s titles was Overseer of the House of Life, which seems to have been a new institution tasked with preserving knowledge and safeguarding original manuscripts of religious and mythological texts, as well as mathematical and medical treatises. “It was a kind of Library of Congress,” says Bárta, “only more secret and sacred.” He believes the tomb owner is likely the same Kairsu who later became renowned as a famous sage in Egyptian memory. His reputation was such that his tomb served as the center of a personal cult that flourished long after the end of the 5th Dynasty.

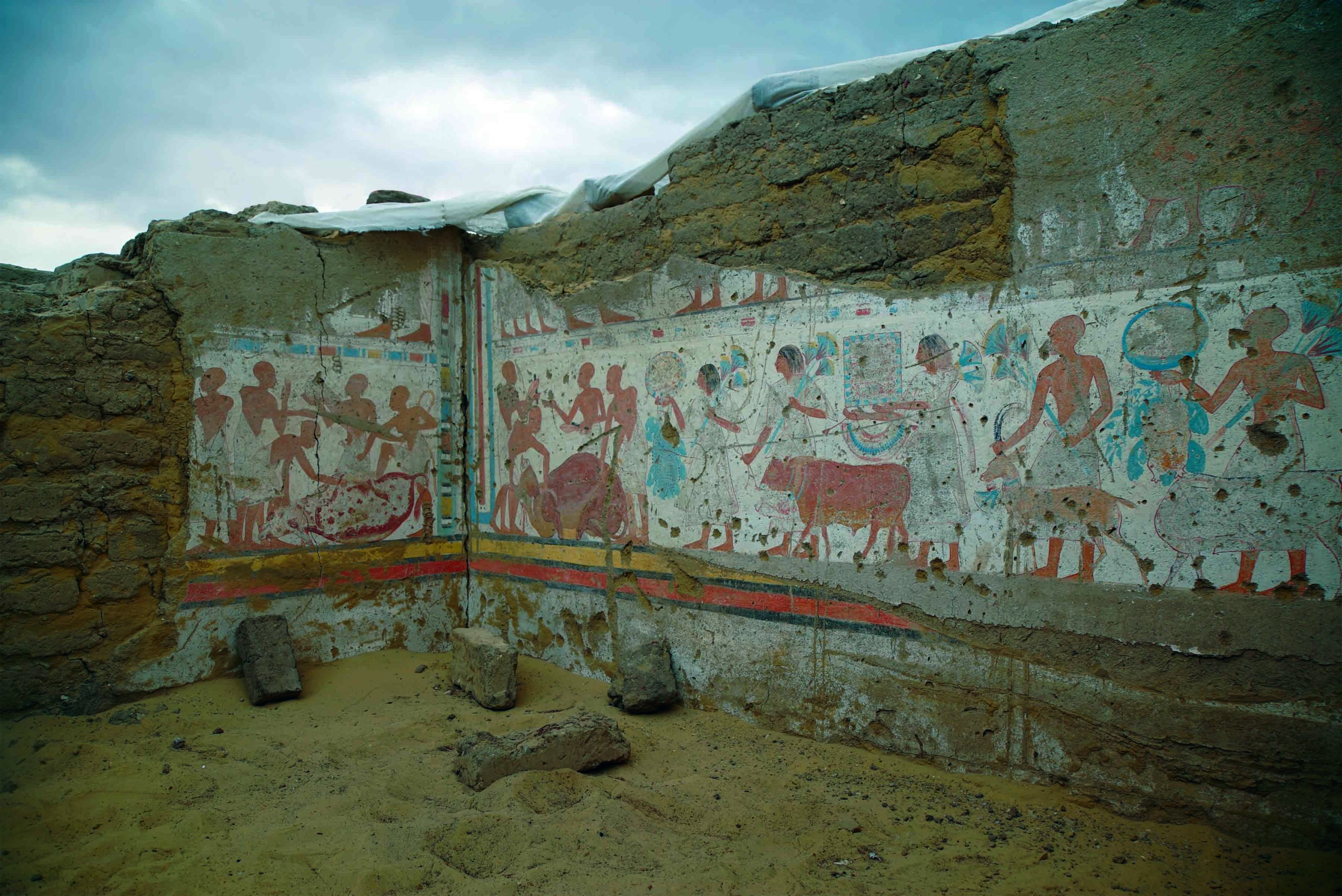

In 2019, Bárta’s colleague Mohamed Megahed unearthed the vividly painted tomb of an official named Khuwy, who served Djedkare Isesi, one of the last 5th Dynasty pharaohs (“Top 10 Discoveries of 2019: Old Kingdom Tomb”). Located near the pyramid of his pharaoh, Khuwy’s tomb features elaborate paintings, including one of Khuwy himself. It also had a substructure modeled on that found in royal pyramids, perhaps another sign of the closing gap in the race for status between royalty and the rising class of non-royal officials.

By the end of the 5th Dynasty, the cult of Osiris was in ascendance. The line’s last two kings did not even build solar temples, and the royal cemetery was moved from Abusir back to Saqqara. The final 5th Dynasty pharaoh, Unis (r. ca. 2353–2323 B.C.), was the only pharaoh of his line not to take a regnal name linked to the god Ra, perhaps further illustrating that Osiris had begun to eclipse the sun god in importance. Unis’ pyramid at Saqqara was also the smallest one ever built during the Old Kingdom, but inside the modest complex was an innovation that would endure for thousands of years. Unis commissioned a series of sacred formulas or spells known as the Pyramid Texts to be carved on the walls of his burial chamber. These include instructions for properly carrying out a funeral and references to the sun that were both codified earlier, perhaps during the 4th Dynasty. But most of the text is devoted to the worship of Osiris. By this time, the god of death had finally become more important than the sun god, upon whose power the earlier 5th Dynasty rulers had relied. Nevertheless, the Pyramid Texts were still intended to reinforce the pharaoh’s legitimacy. “On a symbolic level, the king needed to come up with a new unique form of his extraordinary standing, being a deputy of the gods on Earth,” says Bárta. “The Pyramid Texts were just such a means of achieving this.” Variations of the Pyramid Texts would be included in the tombs of the 6th Dynasty pharaohs, and even in the pyramids of their queens. Within just a few hundred years, the formulas and spells of the Pyramid Texts had spread beyond royal burials, and were inscribed on the coffins of officials throughout Egypt.

As more non-royal families ascended to power in Memphis, the system of local governorships that existed throughout Egypt also grew in importance. These governorships had largely been figureheads during the reigns of earlier pharaohs, but during the 5th Dynasty, it seems that the people who held these offices actually lived in their designated provinces, instead of ruling them from Memphis, as had previously been the norm. As the governors became more autonomous, increasing political and climatic instability after the end of the 6th Dynasty led to the fall of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of a period of political fragmentation known by scholars as the First Intermediate Period (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.). “The seeds of this period of disorder were planted during the 5th Dynasty,” says Bárta. “Any civilization dissolves when its system of values, symbols, and communication disappears. But this collapse did not necessary imply an end.” When pharaohs once again consolidated some centralized power after the First Intermediate Period, non-royal families still wielded great influence and Osiris continued to reign as the god of an underworld where the souls of all Egyptians dwelled. While the mighty pyramids of Giza remained powerful symbols of the Old Kingdom, the fundamental social and religious changes ushered in during the 5th Dynasty would continue to shape Egypt long into the future.

slideshow: Inside an Egyptian Sage's Tomb

At the Egyptian necropolis of Abusir, a team of archaeologists led by the Czech Institute of Egyptology’s Miroslav Bárta recently unearthed the tomb of a 5th Dynasty (ca. 2465-2323 B.C.) official named Kairsu. A powerful scribe and the overseer of an institution known as the House of Life, Kairsu wielded a great deal of authority and was revered as a sage long after he died. All images of the tomb’s excavation in the slideshow are courtesy of the Czech Institute of Egyptology and were taken by P. Košárek.