Some 2,000 years ago, Maya leaders in the city of San Bartolo entered a temple chamber with vibrant murals depicting supernatural beings and mythical humans painted on its walls. Then they destroyed them.

Although the murals—painted exclusively with black, red, yellow, and white pigments—had been executed by three master artists, some cycle of time known only to the city’s priests had ended, and so too had the murals’ life span. The artwork had probably been commissioned by the city’s rulers and had been on display for 50 to 100 years, but the time had come to build a new temple over the old one. This renovation meant tearing down part of the mural chamber, which was located at the base of the temple, known today as the Pyramid of Paintings.

Many of the figures painted on the chamber’s south and east walls were broken by hammer blows, and the plaster fragments containing their faces were removed. The walls were then knocked down. The chamber, which was just above ground level and opened onto a public plaza, was sealed off by a new wall. Builders faced the entire pyramid in a new layer of stone, and a new structure was built. Most of the chamber, which had been created during the sixth such renovation of the pyramid, was left relatively intact. But its remaining murals were hidden from view until 2001, when University of Boston archaeologist William Saturno discovered the chamber during a survey in Guatemala’s Petén rain forest. Until then, the site had been known only to the local Maya community.

Close study of the intact San Bartolo murals revealed that the narrative they told is an ancient version of the creation story Maya people were still recounting when the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century. This story was recorded in an eighteenth-century text known as the Popol Vuh. These murals are among the earliest known Maya wall paintings, but their style and iconography seem to researchers to reach even further back in time. “One of the beautiful things about the discovery of San Bartolo is that it’s a distillation of a lot of key concepts of Maya cosmology in one place,” says archaeologist David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin. “We’re looking at a system of iconography that’s already quite developed and quite old by 100 B.C.”

The chamber’s destruction initially obscured the narrative’s beginning and end. According to Skidmore College archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer Heather Hurst, who codirects the San Bartolo Project with her colleague Boris Beltrán, also of Skidmore College, the destruction was not simply part of the building’s renovation. It was also part of a ritual that commemorated the end of one cycle of time and the beginning of another. Since painting the chamber had imbued it with supernatural significance, destroying some of the murals to clear the way for the renewed temple without acknowledging and managing the paintings’ power could have meant angering supernatural beings. “You can’t just bury it,” says Hurst. “As the new temple is built, you are honoring the temple that came before it.”

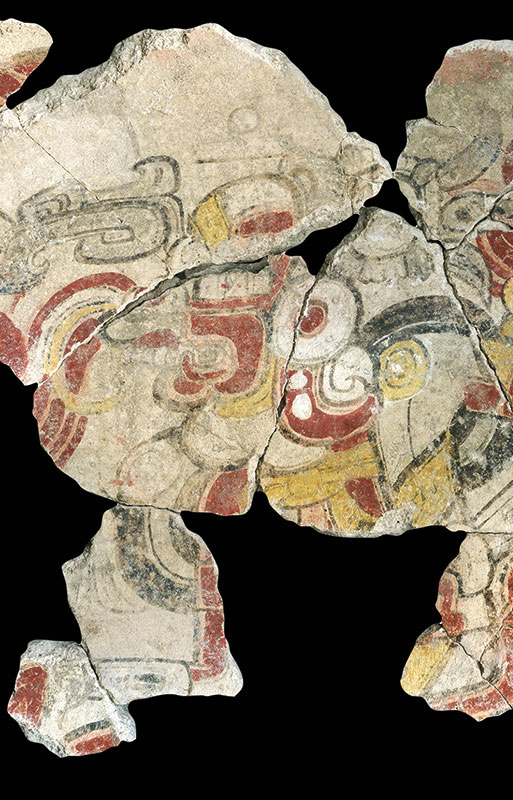

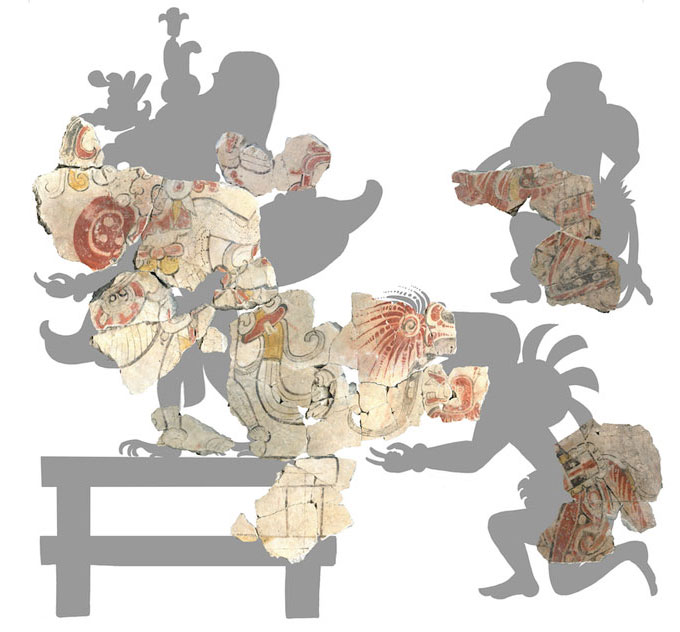

Not all the fragments from the destroyed murals were removed from the chamber during this ritual. About 3,400 of them remained piled on the floor. It took 10 years, beginning in 2002, to excavate and collect them all. It took another six years for the team to reassemble them under the watchful eye of the University of New Mexico’s Angelyn Bass, who has been the project’s principal conservator since the first mural fragments were collected. This painstaking process involved fitting the plaster fragments together like jigsaw puzzle pieces and studying them using X-ray fluorescence, a technique that allows the researchers to identify subtle variations in the amount of the element barium in the plaster. They used this information to match pieces with similar chemical compositions. The reassembled fragments are now on display at the National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Guatemala City.

By the end of the process, the team had reassembled enough painted fragments from the beginning and end of the murals’ narrative to more fully re-create the experience of viewing the murals as they appeared 2,000 years ago. “You would have entered the room and been immersed in a series of stories,” says Hurst. She believes the painted chamber may have been a place where young initiates to the priesthood learned how the cosmos was created.

Stuart sees the murals as a creation story in four acts that not only lays out humanity’s place in the universe, but also establishes the basis for the rulership of the ajaw, or king, and the proper way to make sacrificial offerings to the gods. Reassembling the mural fragments has allowed Stuart, Hurst, and their colleague Karl Taube of the University of California, Riverside, to glimpse a creation narrative that is at once familiar from the Popol Vuh and features previously unknown or obscure Maya deities and religious concepts. These four scenes, each of which seems to be linked to one of the first four days of a ritual calendar, function as a sort of picture book that expresses ancient Maya ideas about community and the role of humanity in the cosmos.

I: CREATION OF THE WORLD

The center of the first scene is a fragmentary image from the demolished east wall that depicts a four-lobed shape representing a cave. As reconstructed by the team, this section of the mural shows two humanlike creator gods seated within the cave and implies that the gods are in the underworld. Between the two gods is a gourd marked with glyphs that say the gourd holds “the blood of humanity.” To the right of the cave is an image of the rain god Chahk sitting on a temple platform and receiving an offering of tamales from a hand that Hurst believes may belong to the maize god’s wife. Tamales were a common Maya offering that evoked maize as one of the foundations of life.

The rest of the scene continues on the intact north wall, where the mural depicts the mountain god known as Witz, whose gaping mouth also represents a cave. Animals, including a jaguar, an iguana, snakes, and birds, emerge between flowers and other plants surrounding Witz’s mouth. This imagery suggests that the cave is an opening into a supernatural paradise known as the Flower Mountain, a sacred place in the cosmology of many cultures throughout Mesoamerica. For the Maya, the Flower Mountain was a place of creation. The sun god emerged from the mountain each morning, while the maize god emerged once a year. It was also where, in a distant time, the ancestors of the Maya originated.

In this scene, four human couples, who may have been the founders of lineages of families who lived in San Bartolo, are shown bringing gifts out of the Flower Mountain and presenting them to the maize god. The god in turn distributes them to the other people in the scene. One of the couples kneels before the god. The woman holds a basket containing tamales, while, in front of her, the kneeling man holds a gourd full of water above his head. On the other side of the maize god, another ancestral couple hold bundles that were taken from the cave, which Taube believes may contain sacred books.

When viewed as a whole, this first scene shows the conditions being created for the birth of humanity and Maya society. The creator gods have made the blood from which humanity will be born, and the ancestors have emerged from the underworld to bring forth maize and water, which form the basis of Maya life and community.

II: BIRTH OF HUMANITY

At the center of the second scene, an image depicts Earth as a turtle floating in primordial waters, reflecting the ancient Maya belief that they lived on the back of a turtle swimming in the ocean. Inside the image of the turtle, the maize god dances and plays a turtle-shell drum.

Immediately to the right of Turtle Earth, a human ruler is shown being enthroned. To the right of the throne, two sets of infant twins burst out of a gourd, which may be the same one that holds the blood of humanity in the first scene. A fifth child emerges from the gourd with arms raised. “With that exploding gourd and the infants, now we’re looking at the birth of humanity,” says Stuart.

To the left of this scene, a series of partially intact images shows the maize god’s enthronement as a mythical ruler, and his birth, death, and rebirth. This image of the god’s enthronement establishes a basis for Maya rulership. The researchers believe the scene would have impressed on ancient Maya viewers that the rulers of San Bartolo received their authority from the maize god.

III: WORSHIPPING THE GODS

The next scene is the best preserved of the narrative. It shows four young men standing and offering sacrifices in front of supernatural trees that anchor Earth at its four cardinal directions. At the top of each tree sits a monstrous bird scholars have named the Principal Bird Deity. According to Taube, the bird deity has a dual nature—it is associated with creation and the sun but also with darkness. The tree closest to the center of the scene has the twisted trunk of a gourd tree. The bird deity is shown descending from heaven to land in it.

All four of the young men making sacrifices, says Taube, are depictions of Hunahpu, one of the mythical hero twins who are the protagonists of many Maya stories. In three of the images, Hunahpu is shown carrying animals that he has hunted, which he offers as a sacrifice. The three animals are a fish representing the underworld, a deer representing Earth, and a turkey representing the sky. In the fourth depiction of the hero, Hunahpu has sacrificed aromatic flowers. In each of the four images he is shown impaling his genitals as an act of ritual bloodletting. Hurst says this scene, on the chamber’s west wall, establishes the basis for the Maya’s negotiations with supernatural powers through sacrifice.

IV: ENTERING THE UNDERWORLD

The last scene is from the destroyed south wall and has been entirely reconstructed from fragments. It takes viewers into the underworld and though it is the least complete scene, it has several identifiable figures. The most complete image depicts an aspect of the sun god known as the solar eagle, according to Stuart and Taube. The deity has the glyph for “sun” painted on his cheek. Above the sun god is a depiction of an obscure god named Wak Tok. Stuart believes that Wak Tok is related to the rain god Chahk, but very little is known about the deity. There is only one other reference to Wak Tok, which dates to A.D. 700 and was found on a stone panel at the site of Palenque in southern Mexico. “We are missing much of this mythical religious knowledge,” Stuart says, adding that it was probably kept in books that have not survived. “We just happen to see little pieces of this lost world, and Wak Tok Chahk is a great example of a Maya deity who was important enough to be in the murals, yet there are only two mentions of him anywhere in the Maya region.”

Two figures stand behind the sun god. One is a depiction of an unknown male deity who has star markings on his legs, indicating that he has some connection to the night. The other wears a headdress made of a bloody femur and an eyeball that sprays blood. Taube has identified this grim individual as the god Akan. “He is the god of alcohol and drunkenness,” says Taube. “He’s also a very unpleasant death god.” A long curving forelock of hair, one of the identifying marks of the maize god, also features on Akan’s headdress. Taube believes these different iconographic elements suggest that the figure of Akan also represents the dead maize god, whom the Maya imbibed in the form of maize beer. The maize god is a central cultural hero in Maya stories. He sets the world in order, says Taube, and even in death he provides something. “When you drink fermented maize beer,” he says, “you’re drinking the rotting maize god.”

Stuart says that while the meaning of the fourth scene remains elusive, it seems to abound in images of death. He points out that the fourth day in the ritual calendar is Ak’bal, which means “darkness,” ending the narrative in the same supernatural space where the first scene begins.

The chamber at the base of the Pyramid of the Paintings isn’t the only space in the building that was furnished with such rich visual narratives. During the same construction phase in which the lower chamber was built, another chamber was constructed at the top of the temple. Its interior was once decorated with its own finely painted murals. The archaeologists have named this chamber Ixim, which is one of the Maya’s words for maize.

These murals feature blue-green, dark green, brown, and purple pigments in addition to the lower chamber’s simpler color palette. They also have a large number of hieroglyphic inscriptions. The style of some of the motifs in these murals is identical to that of those in the lower mural chamber, but they are painted with a much finer hand. These paintings were also destroyed in the same ritual during which the murals of the lower chamber were smashed. About 3,200 mural fragments have been recovered from the Ixim chamber, and they are now being pieced together. The overall narrative told in the mural is still unclear, but facets of the story have begun to emerge. According to Taube, some of these murals reference mountains in distant places. One fragment depicts a pine tree, which is not native to the Petén rain forest. Some of the other fragments show the mountain god Witz devouring blood, which Taube says indicates that Maya artists may have been marking the mountains as a place of sacrifice.

The Ixim chamber’s location at the top of the pyramid made it difficult to access. This suggests that the paintings were viewed mainly by a specialized group of royalty and fully initiated priests, unlike the creation mural at ground level, which would have been more easily viewed by initiates or lower-ranking members of society.

“Public art was a way for rulers to promote ideology and community building,” says Hurst. The lower chamber’s creation story likely functioned in this way, as a means for the people of San Bartolo to learn about their shared history and beliefs. By contrast, the Ixim chamber displays private art, which featured stories and ritual knowledge that would have only been passed on to specialized initiates. “The Ixim chamber is where they really did the business,” says Taube. “The most important rituals were not public.” San Bartolo’s high-ranking citizens would have considered the Ixim chamber a house for the gods and would likely have stored sacred regalia and books there.

Comparing the murals of the lower chamber with those of the Ixim chamber will eventually allow researchers to explore the differences in the public and private messages sent by San Bartolo’s rulers. “The Ixim chamber is another set of murals that could have a revolutionary impact on our understanding of Maya religion and politics,” says Hurst. It’s likely that the Ixim chamber murals told stories that the Maya understood on many different levels, much like the narrative in the lower chamber. The people of San Bartolo probably understood that the different stories the murals told were much greater than the sum of their parts. For instance, says Stuart, once viewed all together, the murals of the lower chamber seem to follow a cycle of solar movement. “Sun emergence, zenith, sunset, nadir,” says Stuart. “It’s like they’re grafting a grand narrative onto that cycle. It’s a perpetual story.”