In Talbot County, Eastern Shore, State of Maryland, near Easton, the county town, there is a small district of country, thinly populated, and remarkable for nothing that I know of more than for the worn-out, sandy, desert-like appearance of its soil, the general dilapidation of its farms and fences, the indigent and spiritless character of its inhabitants, and the prevalence of ague and fever. It was in this dull, flat, and unthrifty district or neighborhood, bordered by the Choptank river, among the laziest and muddiest of streams surrounded by a white population of the lowest order, indolent and drunken to a proverb, and among slaves who, in point of ignorance and indolence, were fully in accord with their surroundings, that I, without any fault of my own, was born, and spent the first years of my childhood. —FREDERICK DOUGLASS, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881)

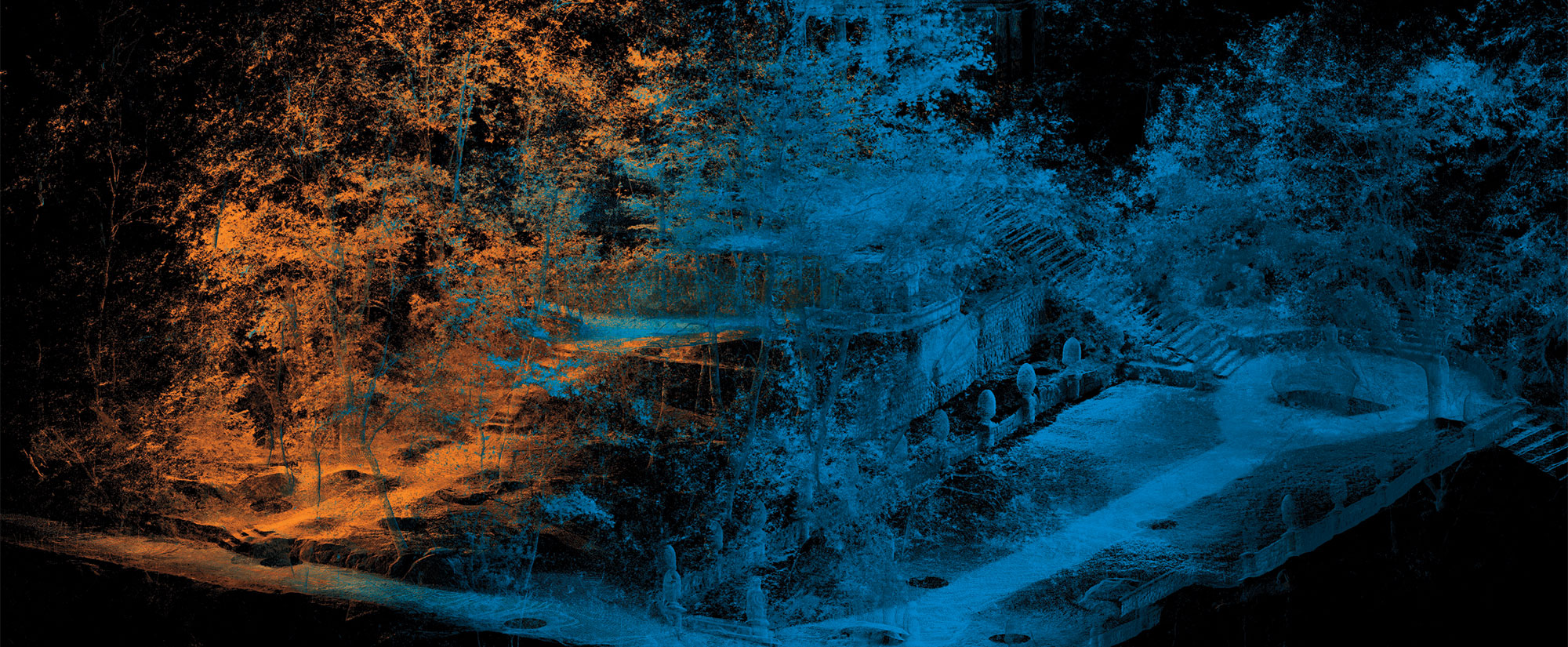

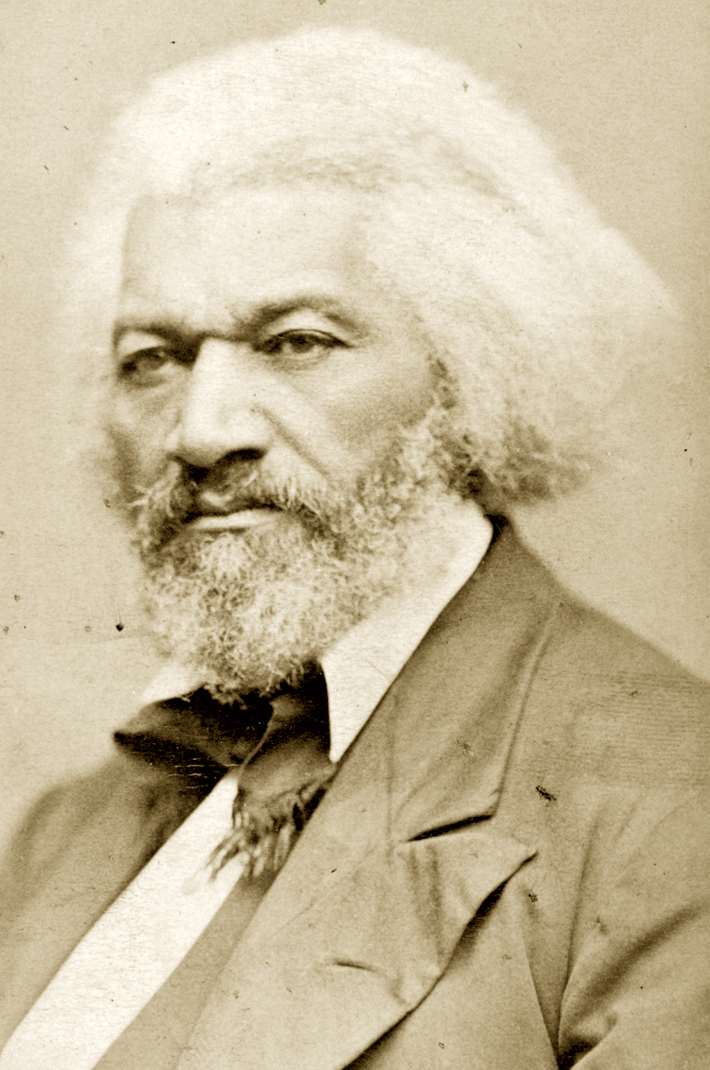

Under the boughs of a huge tulip poplar, buried among clumps of roots and piles of oyster shells, is the brick foundation of a building, a remnant of a once-thriving slave community. For 18 months in the early nineteenth century, it was home to a young Frederick Douglass, the future African-American statesman, diplomat, orator, and author. Here, at the age of seven or eight, a shoeless, pantless, precocious Douglass first saw whippings and petty cruelties. Here, he first realized he was a slave. “A lot of the horror that comes through his autobiographies is grounded in those months that he was there,” says James Oakes, a historian at the City University of New York who is working on a book about Douglass’s relationship with Abraham Lincoln. The modest excavation at Wye House Farm, a 350-year-old estate on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, has yielded sherds, buttons, pipe stems, beads, and precious knowledge about everyday slave life, and is allowing the descendants of that slave community, many of whom live in the nearby rural African-American town of Unionville, to reclaim a lost cultural hertiage.

A team of archaeologists and students started digging here in 2005 after archaeologist Lisa Kraus proposed the dig, on the basis of Douglass’s descriptions of the site, to Mark Leone, director of the urban archaeology field school at the University of Maryland. Before beginning the excavation, Leone approached St. Stephen’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, the social and religious center of Unionville, to ask what the people of the community wanted to learn from the archaeology. “You should ask the people who think it’s their heritage what they want to know about it,” Leone says. “The answers automatically dissolve the difference between then and now.” This, he adds, is the heart of social archaeology, working with descendant communities and understanding that the past and present inform one another. The people of Unionville wanted to know about slave spirituality, what remained of African life, how the owner of the slaves did or did not support freedom, and how slaves found the strength to survive. They are questions a single dig is unlikely to answer, but they have opened an avenue of dialogue between the archaeologists and the people to whom their work matters most.

A sharp, fetid smell wafts off the nearby cove, where swarms of insects form a halo over still water. Leone, a tall, fair anthropologist who has spent his career studying class and race in the historical landscape of Annapolis, speaks slowly and deliberately. “What we have discovered is there’s archaeology everywhere,” he says, as a team of students profile and photograph the site under the tulip poplar behind him. “We’ve only scratched the surface.” Waving his hand across the rolling landscape bordered by the cove on one side and a farm road on the other, he explains that it was once all part of a slave community buzzing with activity.

Leone and Kraus, a graduate student at the University of Texas, have for the last two field seasons led this dig, which is on the grounds of a grand plantation that has been, and still is, privately owned by one family—the Lloyds, one of the founding families of Maryland. The team so far has uncovered three structures packed with domestic and commercial artifacts of slave life, and they expect to find more next season.

Mary Tilghman, the Lloyd family matriarch and eleventh-generation descendant of Edward Lloyd, who settled the property in the 1660s, receives guests in the well-appointed, hunting-themed south parlor of the estate’s late Georgian mansion, just a hundred yards or so from the dig site. Tilghman, a proper yet lively woman of 87, dressed in a long khaki skirt and collared blouse, has piercing blue eyes and pale skin like creased parchment. She taps her aluminum cane on the hardwood floor as she speaks. “I think it’s fascinating and I think seeing something, rather than assuming something was there, that’s intriguing, This is probably a very foreign culture to a great many people.”

Tilghman, who rides around the estate on a golf cart with bundles of dried flowers tied to the back, doesn’t live in this mansion, but in a smaller building known as the Captain’s house, named for Captain Aaron Anthony, the farm manager who actually owned the young Douglass and is believed to have been his biological father. Tilghman clearly doesn’t condone the slavery practiced by her ancestors and their employees, but she doesn’t feel the need to apologize for it either. Yet even though she is a private woman, she has opened her property to archaeologists, reporters, and descendants of the slaves her family once owned. “She could have refused quite gracefully and no one would have thought any the worse of her,” says Kraus. “[The Lloyds] have contributed hugely to the founding of the country and the ideas that it’s based on, but at the same time there’s this—it’s not even a skeleton in the closet, it’s on the lawn, right there.”

This site is distinguished from other slave community excavations by an embarrassment of primary sources. In addition to Douglass’s detailed descriptions of slave life, in the 1960s architectural historian Henry Chandlee Forman drew maps of the estate himself or traced them from disintegrating maps in the family archives. There are also aerial photographs from the 1930s and 400 boxes of Lloyd family archives, which include both business documents and personal letters and diaries, stored at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore. Most importantly, there is a very rare commodity, the people of Wye House Farm and Unionville and their family lore and memories of childhood. “You play these primary sources off of each other,” says Leone, comparing, for example, the aerial photographs with Forman’s maps and Tilghman’s childhood recollections. At the farm’s height in the mid-1800s, the Lloyds may have owned more than a thousand slaves spread across dozens of corn, tobacco, and livestock farms in the area and beyond. In a single transaction in 1830, according to the archives, they spent $24,000 on 72 slaves.

During the Civil War, some local slaves enlisted in the Union Army, and their owners were compensated $300 each. Upon returning from the war, many of these newly freed men returned to the places that they knew. When 18 soldiers from this area—many of whom are thought to have come from Wye House Farm—returned, an abolitionist Quaker named Cowgill offered them a reasonable lease on land and the town of Unionville was founded. Just down the road from the farm, Unionville today is a poor but tidy rural town of single-family homes. The tightly knit and proud community is centered around St. Stephen’s and its adjoining graveyard, where the 18 soldiers are interred. Some of the names on the gravestones—Roberts, Demby, Bailey (Douglass’s birthname)—appear on the Lloyd’s slave rolls. Douglass even mentioned one, “Uncle” Isaac Copper, by name. Today, as in Douglass’s day, old money and rural poverty, divided along racial lines, sit side-by-side.

Then there were a great many houses, human habitations full of the mysteries of life at every stage of it. There was the little red house up the road, occupied by Mr. Seveir, the overseer; a little nearer to my old master’s stood a long, low, rough building literally alive with slaves of all ages, sexes, conditions, sizes, and colors. This was called the long quarter. Perched upon a hill east of our house, was a tall dilapidated old brick building, the architectural dimensions of which proclaimed its creation for a different purpose, now occupied by slaves, in a similar manner to the long quarters. Besides these, there were numerous other slave houses and huts, scattered around in the neighborhood, every nook and corner of which, were completely occupied. —FREDERICK DOUGLASS

The bustling slave community was located on the estate’s “long green,” an area nearly a mile long and 300 feet across at its widest point, and which runs along a farm road between the mansion and the cove. In Douglass’s time, it accounted for much of the business of the farm, such as carpentry and metalwork conducted by skilled slaves who lived here. The red overseer’s house that Douglass described still stands, even though swaths of the long green have since been tilled and incorporated into fields of soy and corn.

The excavation team, which included three African-American students in the 2006 season, sought to understand how the buildings there were used and the specifics of slave life, such as trade and skilled labor. The crew used shovel tests and maps to identify the likely spot, in an untouched portion of the long green, of a two-story slave quarters described by both Douglass and Forman, only to find that it was already occupied by the tulip poplar—six feet in diameter and fifty feet tall. With insects whapping against their faces and clothes and surprisingly large lizards scuttling underfoot, the team spent the summer cutting through and digging around a dense network of roots to uncover a brick foundation full of domestic artifacts, including sherds of heavy ceramics and porcelains, a spoon, a thimble, beads, a knife blade, and hundreds of bones from domestic animals, including pigs, cows, and chickens, and wild animals, including rabbits, deer, turtles, and fish. The area had never been plowed, so despite the roots the site was largely intact.

“We have a history of African-American life that has this amazing time depth,” says Kraus. “Archaeology really gives us information about their day-to-day practices.” For example, pottery finds suggest that the slaves of Wye House Farm did not have access to a market or make ceramics themselves—most of what they used was passed down from the Lloyds. Other items, such as beads, buttons, and decorations, were probably not passed down and may have come, by night and by canoe, from a secret, prohibited trade network with other slave communities. Even though the slaves were worked almost constantly, and getting caught would have resulted in a beating from an overseer, they took great risks to build lives beyond the fields. “I don’t think that’s really been documented before,” says Kraus. With further analysis of the artifacts and where they were found, she hopes to discover how slave life may have changed over the decades that the site was occupied.

With the maps and further poking around, the team also found a large foundation overgrown with vines and poison ivy next to the water line. Tilghman remembered this structure from her childhood as a corn crib, while Forman described it as a carpenter’s workshop. The structure was likely repurposed many times; it included chunks of sturdy eighteenth-century English brown stoneware alongside animal bones, confirming that it may have been a work building for carpenters and suggesting that skilled slaves here likely lived in the same places that they worked. A third structure, which does not appear on Forman’s map, may have been a makeshift dwelling or lean-to, and yielded hundreds of hand-wrought nails and a posthole. They have also found, throughout the dig sites, broken tools, parts of carriages, and what appears to be a hitching post. Under the tree, the team also found and quickly reburied a more than 2,000-year-old Native American grave, and there are probably more like it.

With the three structures, the archaeologists began to piece together the bustling green Douglass described. “Everything, to a detail, appears to be exactly what he said it was,” says Kraus, citing the presence of workshops, smaller unmapped huts or lean-tos, and crowded dwellings occupied over many years, side-by-side and all within sight of the master’s and overseer’s houses.

It was a little nation by itself, having its own language, its own rules, regulations, and customs. The troubles and controversies arising here were not settled by the civil power of the State. The overseer was the important dignitary. He was generally accuser, judge, jury, advocate, and executioner. The criminal was always dumb—and no slave was allowed to testify, other than against his brother slave. —FREDERICK DOUGLASS

To the people of Unionville, the finds at Wye House Farm, while not spectacular, are a tangible link with a past that is much discussed but largely forgotten, one that lingers in unheard African-American voices and the modest homes of Unionville. “It’s an exploration of the history of modern social issues,” says Kraus. “It doesn’t make people comfortable and happy, but they are interested.”

Just days after the dig ended for 2006, the team presented their finds to the people of Unionville at the Roberts family reunion, an annual event that draws hundreds of Unionvillians from here and around the country. According to William Roberts, a self-professed “poor county boy” from Unionville who is now president and CEO of Verizon Maryland, as many as 60 percent of the people at the reunion are likely to have ancestors who worked at Wye House Farm. In the domestic remains of his ancestors, Roberts says, he found strength. “So many people today do so little with so much, and they did so much with so little,” he says. “If we’ve overcome this, there’s no excuse for us not being able to overcome anything today.” His 16-year-old niece, Ariel Roberts-Brown, found beauty. “When you find a little button or a little bead that perhaps was a necklace, you learn that something mattered to them,” she says.

“It was like someone recognizing that we existed then,” says Harriette Lowery, who grew up in Unionville and returned to live there when her grandparents passed away. “It was almost like touching them.”

The people of Unionville may not have found the answers to their questions about Africa and spirituality (although those questions were answered to some extent in Annapolis, where Leone found spirit caches, collections of beads, crystals, and pins buried nears hearths and doorways, but this interaction, says Kraus, is central to the project. “I think archaeology runs on public interest,” she says.

According to Kraus, this social archaeology is about reclaiming a history and carrying on Douglass’s legacy. “Frederick Douglass’s project was to enfranchise the disenfranchised,” she says. “He’s part of a tradition of black scholarship that’s been overlooked by archaeologists doing African-American archaeology.” Even if Douglass at times exaggerated the brutality of slave life in Maryland, as some including Tilghman, Leone, and many scholars surmise, he was providing a voice to the voiceless. Social archaeology can do the same thing. Through a story of slavery and cruelty, Douglass provided a discourse on freedom; archaeology, by bringing free African Americans in direct contact with their enslaved ancestors, can help reclaim the trials of slave life as sources of strength.

“The more it is open to us, the more we can heal from it,” says Lowery.

Later in life, when Douglass was well-known and widely respected, he returned by steamer to Wye House Farm as a free man. As he was entertained by a Lloyd family descendant, he saw, in the same place he knew as a child, a dramatically different world.

******************************************

I found the buildings, which gave it the appearance of a village, nearly all standing, and I was astonished to find that I had carried their appearance and location so accurately in my mind during so many years. . . . From this we were invited to what was called by the slaves the Great House—the mansion of the Lloyds, and were helped to chairs upon its stately veranda, where we could have a full view of its garden, with its broad walks, hedged with box and adorned with fruit trees and flowers of almost every variety. A more tranquil and tranquilizing scene I have seldom met in this or any other country. —FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Originally published in the November/December 2006 issue