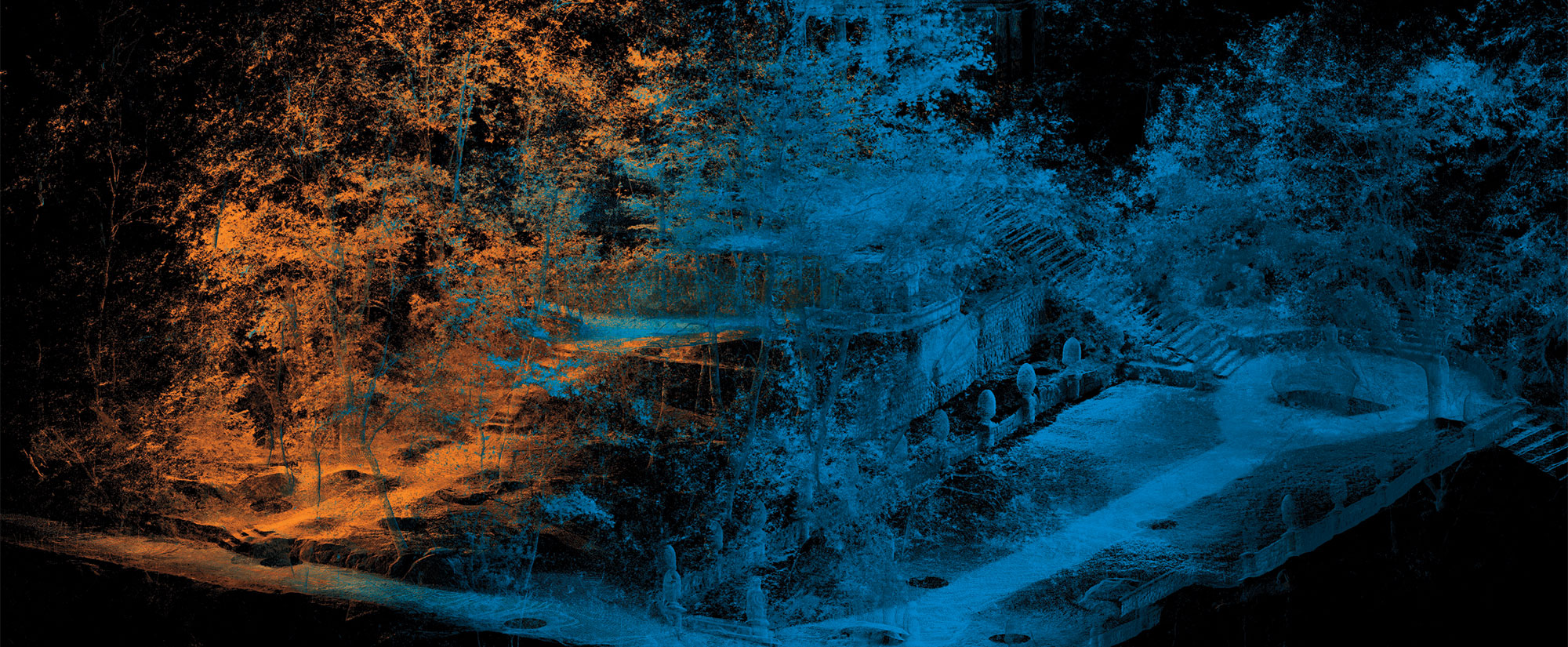

(Courtesy Jean Clottes, Chauvet Cave Project)

Dating

After the cave paintings were discovered in December 1994, the first question archaeologists faced was, how old are they? At first glance, the paintings' technical sophistication made them seem relatively recent, perhaps 10,000 to 15,000 years old. Radiocarbon dating of the charcoal in the black pigments, however, showed that the earliest paintings in the cave were made 35,000 years ago. The date overturned the idea that Europe's earliest cave paintings were crude and simple and that artistic techniques had to be refined over thousands of years before the finest cave art could be made. More than 80 radiocarbon dates have been taken from the torch marks and paintings on the walls, as well as the animal bones and charcoal that litter the floor, providing a detailed chronology of the cave. The dates show that the artwork was made in two separate periods, one 35,000 and one 30,000 years ago.

Cave Bears

The way that people used Chauvet Cave was shaped by their interactions with the cave's primary residents, the now-extinct cave bear. Humans do not appear to have lived in the cave and it is likely that the paintings were made in the spring or summer when the bears would not have been hibernating. The bears themselves seem to have held a special significance for the artists who worked in the cave, in addition to being subjects of the artwork. A bear skull was placed on top of a large, flat rock in an area called the Skull Chamber. There is evidence a fire was lit before it was set there, raising the possibility that it had some kind of ritual function. More than 190 bear skulls have been found in the cave, giving paleontologists an enormous amount of information about a species that disappeared 20,000 to 25,000 years ago and used caves in ways that were similar to how humans used them. The bears organized the space within the cave by digging shallow depressions in the cave floor, possibly as sleeping areas. They also made their own marks on the cave walls by repeatedly raking their claws across the limestone, incising sets of four parallel lines. In some cases the paintings in Chauvet Cave are a kind of collaboration between humans and bears. Human artists incorporated claw marks into some of their paintings. In others, cave bears made their marks on top of the paintings, adding a new element to the images that cave art expert Jean Clottes calls "the magic of the bears."

Tracings

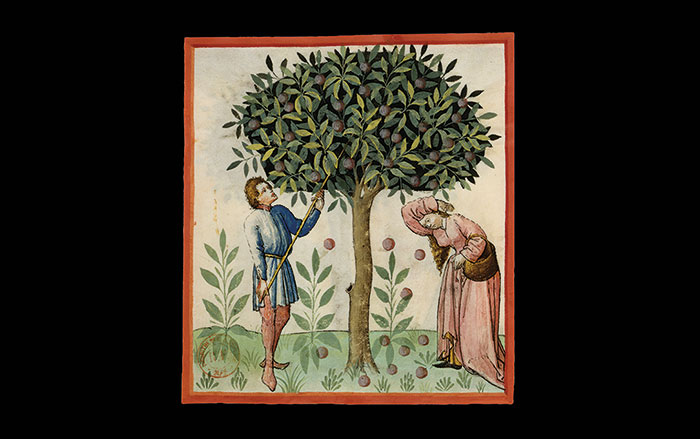

Studying the paintings is an intensive process that begins by going into the cave to photograph an image. The digital photograph is enlarged in the laboratory. Then a researcher places a sheet of transparent plastic over the photo and traces the image in as much detail as possible. The tracing is then brought inside the cave to check it against the original painting. At this stage the researchers also move a light at different angles around the painting to reveal any hidden details of the image. The process forces the researchers to put themselves in the place of the painters and understand the variety of techniques that were used to make the artwork. Some of the images were made after scraping away a layer of dark brown clay that covers the cream-colored limestone walls. Most were made by drawing with a piece of charcoal, or painting with a brush or finger covered in red pigment, or by spitting pigment against the wall. As the tracing is created, the research team learns how the images were composed and the order in which the lines were drawn. "People ask me, 'Why don't you use photos?'" says Clottes. "Well, a photo is not a study...the human mind is still the better computer."