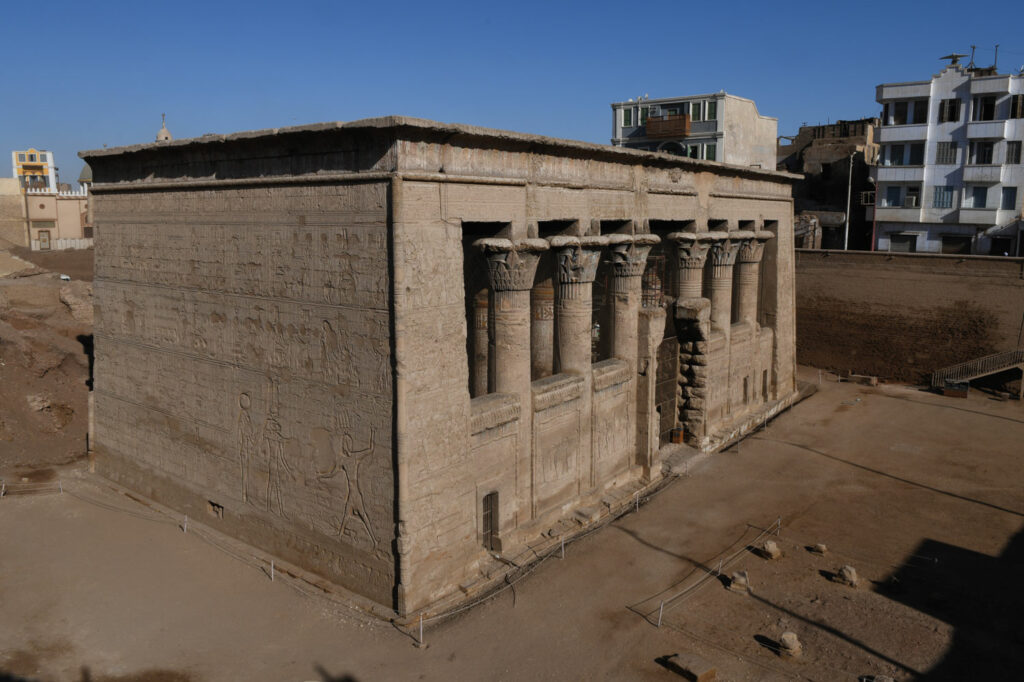

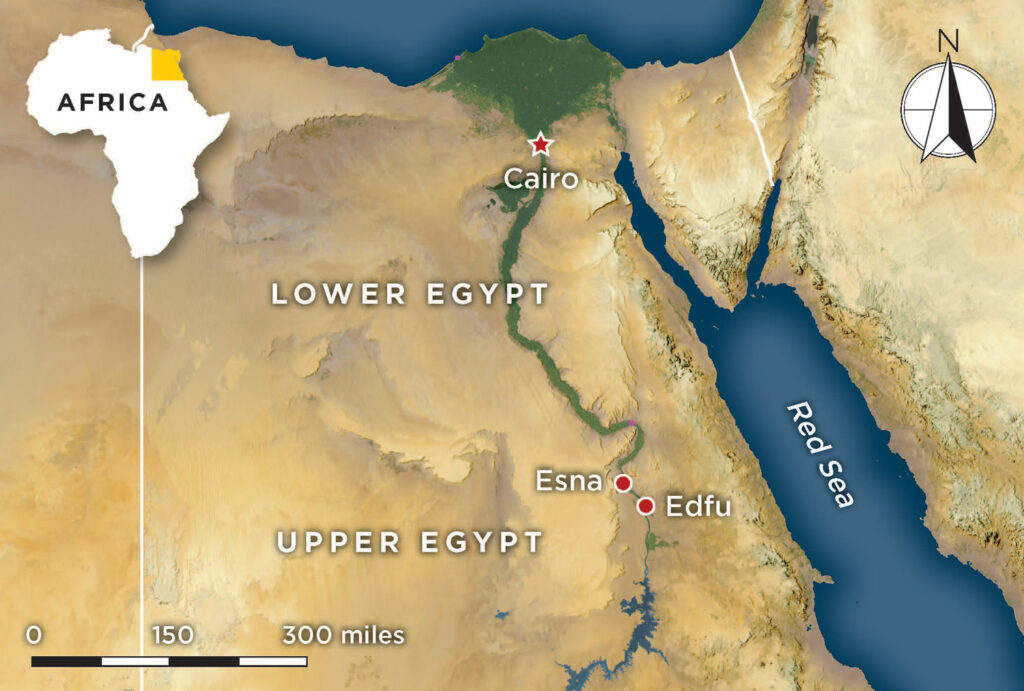

Some 100 major temples towered over the landscape of Roman Egypt, though today only six still stand. One of the best preserved sits in a residential neighborhood in the modern city of Esna on the west bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt. The temple was dedicated to the creator god Khnum, his family, and the goddess Neith. Now 30 feet below street level, the temple’s red sandstone pronaos, or entrance hall, is all that survives of what was once a larger complex. The other remnants of the temple, which stood behind the hall, are now buried beneath the city. In antiquity, the hall, which measures 120 feet long and 65 feet wide and stands 50 feet high, would have dwarfed the rest of the temple. Larger-than-life scenes carved on each of its exterior walls offered ancient worshippers a mere hint of the resplendent painted reliefs that still cover nearly every inch of the hall’s interior.

Construction of the temple’s pronaos began after the emperor Augustus’ conquest of Egypt in 30 b.c., but its decoration required centuries to complete. The entrance hall was constructed directly against the facade of the temple, which had been built during the rule of the pharaoh Ptolemy VI (reigned 180–145 b.c.), one of the kings in a dynasty of Macedonian royals who governed Egypt from 304 to 30 b.c. Throughout the hall, oval cartouches with the names of a long line of Roman emperors attest to the protracted time it took to finish the building and its decoration. Construction of the hall was likely completed in the mid-first century a.d., under the emperor Claudius. It took artisans until the reign of the emperor Decius, 200 years later, to finish carving and painting the building’s elaborate relief decoration.

In the late third or early fourth century a.d., by which time the temple had presumably been closed, the residents of Esna began to dismantle its main sanctuary and repurpose the building blocks to build canals. They used the pronaos as a shelter for the next 1,500 years, and, in the nineteenth century, it became a warehouse for storing cotton and ammunition. Over that stretch of time, fires lit inside for illumination and warmth gradually coated the bright paintings on the ceilings, columns, and interior walls in thick layers of dirt and soot. Parts of the pronaos were buried beneath sand until the twentieth century.

In the 1950s, Egyptologist Serge Sauneron cleared away the debris obscuring portions of the exterior walls. He then turned to the interior, recording those carved reliefs and hieroglyphic inscriptions that were visible to the naked eye. Although Sauneron gradually published the inscriptions and select drawings of the pronaos’ decorations, his death in 1976 halted this documentation project. Most of the inscriptions he transcribed were never translated.

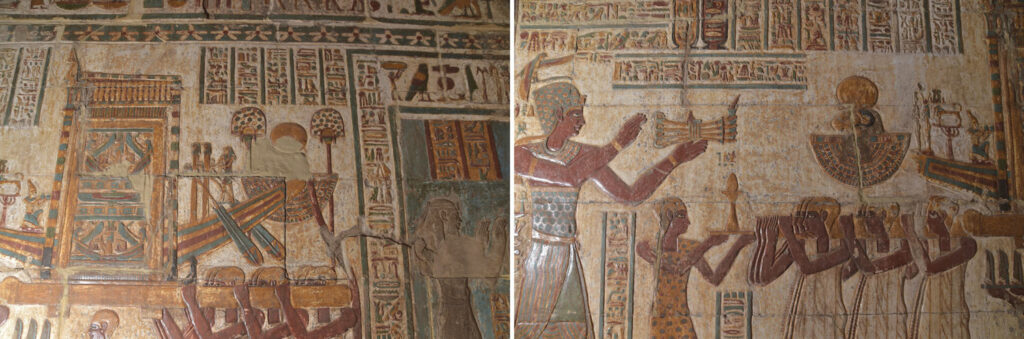

The hall’s reliefs were still completely covered in soot when, in 2018, a joint Egyptian-German team, led by Egyptologist Christian Leitz of the University of Tübingen and Hisham El-Leithy, undersecretary of state for documentation of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA), began to restore the designs’ vibrant colors to their former brilliance. Using primarily distilled water and alcohol, MoTA conservators supervised by Ahmed Emam have now cleaned the hall’s 18 interior columns, all seven of its ceiling bays, and sections of its southern and western walls. In the process, they have revealed hitherto hidden images and nearly 200 painted inscriptions on the ceiling and crossbeams that Sauneron hadn’t been able to see. “Salt crystallization had affected the colors and caused some flaking of the reliefs,” El-Leithy says. “The conservation team cleaned the layers of soot, dust, and dirt, and the bright colors of the paintings and inscriptions can now be appreciated.”

As work continues, researchers are beginning to discover the many interconnections among scenes and inscriptions, even across parts of the hall where decorations were completed centuries apart. “In our view, there was a general master plan for everything,” says University of Tübingen Egyptologist Daniel von Recklinghausen. “Once the hall was finished by the mid-first century a.d., someone, or perhaps many people, made a master plan for the decoration that incorporated everything—the exterior and interior walls, the columns, and the ceilings, all of it.” The team has uncovered and photographed scenes that reveal how ancient Egyptians depicted and worshipped their gods and how they conceived of the universe through the astronomical objects and astrological signs that they used to adorn the ceiling.

DEITIES

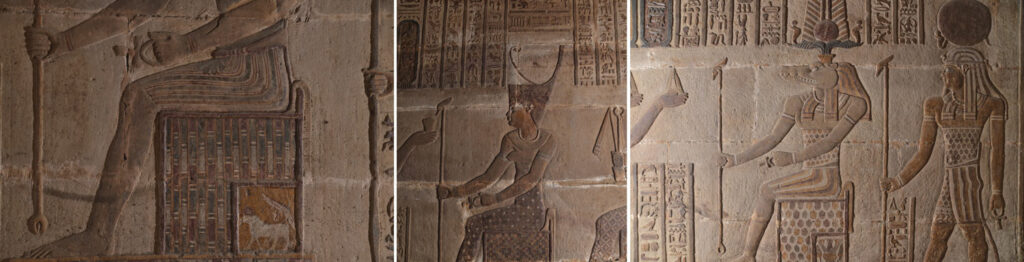

During the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, Egyptians continued to worship their traditional gods even as foreign rulers introduced new deities. Priests oversaw the construction of new temples and cult centers dedicated to major deities of the Egyptian pantheon, who were venerated alongside local gods in cities throughout Upper and Lower Egypt. Although worship of Khnum dates back some 4,000 years, the origins and evolution of his cult at Esna and other religious centers are opaque. Khnum was always connected with creation, fertility, and the Nile. He was usually depicted as a ram, or with a ram’s head, and occasionally as a crocodile. By the time of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 b.c.), Khnum was portrayed as fashioning all living things on a potter’s wheel. At Esna, he was venerated as Khnum-Ra, signifying the addition of the sun god Ra to his divine power. Leitz suggests that the choice of red and yellow, both commonly used to depict the sun, as the dominant colors for the reliefs in the entrance hall might symbolize this connection between Khnum and Ra.

At some point, perhaps during the second century b.c., the cult of Khnum in Esna came to encompass another creator deity, the goddess Neith. Hymns carved on the hall’s columns and walls praise Khnum and Neith as the Lord and Lady of Esna. According to a myth recorded on one of the columns, Neith, who is called “mother of mothers,” gave birth to Ra and other gods by speaking their names. “Both these deities are responsible for the creation of a whole universe,” von Recklinghausen says. “You find this idea of creation everywhere in the temple.”

Each column in the pronaos features ritual scenes on its lower part and is inscribed with 28 vertical panels of hieroglyphs, each 13 feet tall. “These texts describe the cult of the gods of Esna, which we don’t have at this length in any other temple,” says Leitz. “There are hymns and litanies to Khnum, Neith, Khnum’s other consorts—Menhit and Nebtu—and his son Heka.” One column preserves a 143-verse litany to Khnum-Ra praising everything the god has brought into being.

The layout of the inscriptions provides a remarkable example of the ingenious interactions between text and images in the pronaos. The 28 panels on each column are evenly spaced around its circumference. On some panels, Leitz explains, hieroglyphs face directly toward pictorial scenes that illustrate offerings described in the text and, in one case, toward a small door through which offerings were brought into the temple.

RITUALS

At the temple of Khnum in Esna, as at every Egyptian temple, priests performed daily rituals. In the entrance hall, however, activities were likely limited to special celebrations that occurred on many dates throughout the year, chief among them New Year’s Day. A lengthy calendar of festivals beginning on that day is inscribed alongside the hall’s southeast and northeast doors. Next to each date is a brief description of that particular day’s main rites. In all, the festivals listed on the calendar amount to 90 days of celebrations per year. “More or less every second week there would have been a festival taking place,” von Recklinghausen says. “There seem to have been two or three main feasts as well as more frequent smaller feasts.”

Although the entrance hall features a wealth of texts and scenes concerning the feasts, rites, and offerings on festival days, its function as part of these proceedings is unclear. “We’re not really certain what happened inside the pronaos,” says Leitz, “but we do know that the temple’s main entrance was only opened during the big feasts.” Inscriptions specify the conditions worshippers were required to meet to enter the temple precinct on these days. “They had to be clean and to abstain from intercourse for eight days before,” Leitz says. “Women and foreigners had no access at all. They had to wait outside the temple.”

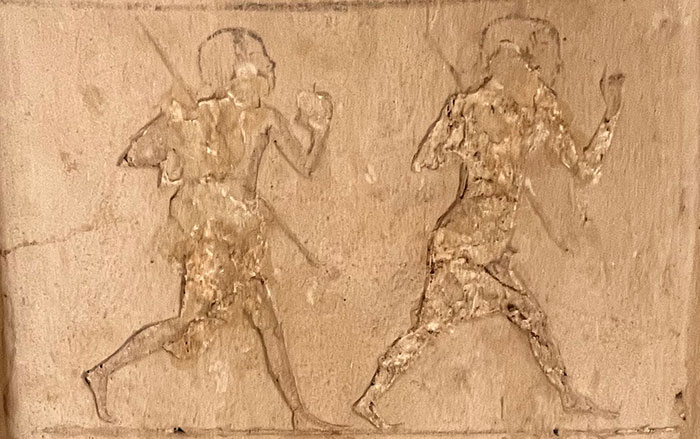

Recently cleaned reliefs on the pronaos’ interior walls provide tantalizing clues as to what the rites honoring Khnum involved. One scene shows the emperor Trajan (reigned a.d. 98–117) dedicating four incense burners to the god, while a priest clad in leopard skin standing in front of him offers Khnum a potter’s wheel. Another portrays priests carrying the solar boat of Khnum, in which the god’s shrine sits, out of the temple’s inner sanctum. On special occasions, such processions would have traveled from the inner sanctum into the entrance hall, down its central aisle, to the throngs of worshippers gathered outside. “I think the pronaos was a very important part of this ritual procession and the feasts,” says von Recklinghausen. “It was probably the first point where the procession halted so that hymns could be read aloud or sung.”

HEAVENS

By the time artisans began to create the decorations in the temple of Khnum at Esna, Egyptians had observed the paths of the sun, moon, and stars for thousands of years, and their knowledge of astronomy formed the foundations of their religion. They believed that certain celestial bodies were incarnations of their gods; for example, the rising sun symbolized Ra’s creation of the world, and its path reflected his daily rebirth. Thus, representations of astronomical phenomena were fitting subjects for Egyptian temples.

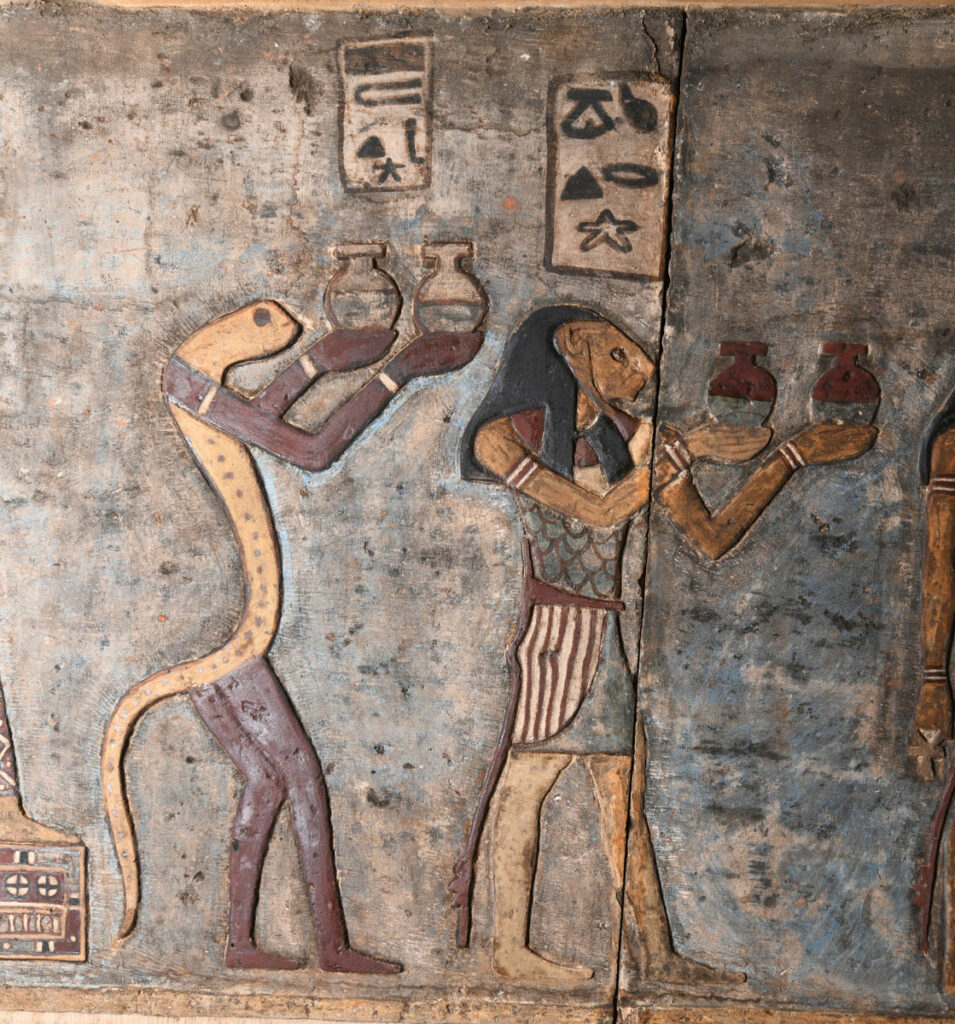

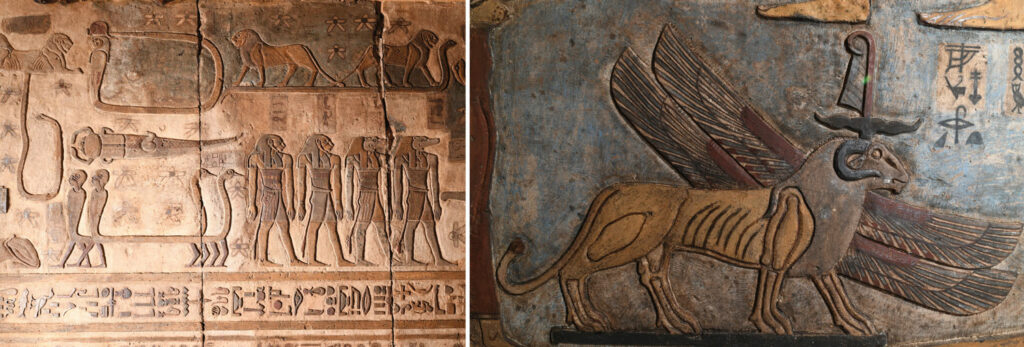

Each ceiling bay of the pronaos features a particular astronomical theme surrounded by stars. The three bays on either side of the central aisle show the lunar cycle, with the deities of the waxing and waning moon standing on disks; 36 figures called decans, stars or constellations that measured the 12 hours of the night; the course of the sun, which is shown on two bays; the 12 signs of the zodiac; and various other constellations. Peculiar hybrid creatures—including winged snakes and a bird with a crocodile head and four wings—are depicted across the ceiling and are thought to represent constellations. “Most of these creatures are accompanied by rectangles in which we found painted inscriptions that give us the names of these strange beings,” Leitz says. “But this doesn’t necessarily mean we know which stars they refer to.”

The ceiling also contains representations of much better-known constellations that played crucial roles in Egyptians’ mythology and conception of the cosmos. A bay on the north side of the hall depicts a few of the most important deities in the Egyptian pantheon. On one side of the bay is the constellation Orion, depicted as the god Osiris. He is accompanied by Sothis, the divine personification of Sirius—the brightest star in the night sky—in the guise of Isis, Osiris’ wife and sister. “Orion and Sothis were the two main deities of the southern sky,” says Leitz. “Orion turns his head to Sothis. The astronomical reason for this is that Sothis rises a bit more than an hour and a half later than Orion.” In Egyptian mythology, Osiris was murdered by his brother Seth, the god of confusion and disorder. Isis was able to reassemble her husband’s dismembered body, bringing Osiris back to life, after which he became god of the underworld.

On the other side of the bay, a bull’s leg is tethered to a chain held by a hippopotamus goddess. The leg represents the Big Dipper, whose seven bright stars are depicted surrounding it. “The Big Dipper is a representation of the god Seth,” Leitz says. “Even though Osiris was reanimated after his murder, Seth was interested in killing him again. This hippopotamus deity is therefore preventing the Big Dipper from descending too far under the horizon into the underworld.”

During the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649

Orion and Sothis also appear in the pronaos’ southernmost ceiling bay. Under a border depicting the sky goddess Nut swallowing the sun, the deities are shown riding in separate boats, with Orion in the lead looking back at Sothis. After conservation, the researchers found a hieroglyph featuring 10 stars painted above the deities. “On the night before the Egyptian New Year festival, Orion rises in the tenth hour, and Sothis follows in the twelfth hour,” says Leitz. “After approximately seventy days of invisibility in the night sky, Sirius rises for the first time in the east.” This astronomical event occurred in mid-July and marked New Year’s Day for the Egyptians, which for thousands of years was one of their most important festivals. It coincided with the annual Nile flood. In the scene, Orion and Sothis are followed by Anukis, the goddess of the inundation of the Nile, who was also responsible for the river’s recession 100 days after the new year.

ZODIAC

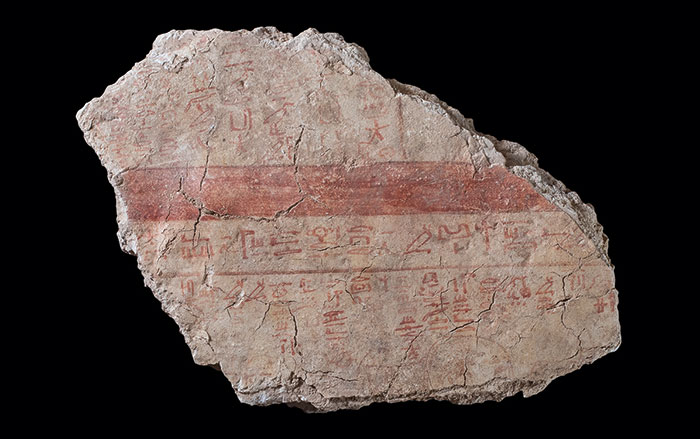

One of the most remarkable decorations in the entrance hall of the temple of Khnum in Esna is the representation of the zodiac, the primary subject of a ceiling bay near its southern end. The zodiac system was devised by the Babylonians in Mesopotamia around 4,000 years ago and was likely introduced to Egypt by the Ptolemies toward the end of the fourth century b.c. It soon became popular among Egyptians, who decorated their tombs with zodiac signs and inscribed their horoscopes on ostracons, broken pottery pieces used as writing surfaces. “In the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, the twelve constellations of the zodiac would have been depicted on the ceilings in every temple in Egypt,” Leitz says. “It was nearly the only non-Egyptian decorative element in these temples.” The zodiac ceiling bay in the pronaos is one of only three complete sets of astrological signs preserved from Egyptian temples.

The 12 zodiac signs are carved in two groups of six, which are separated by a hieroglyphic inscription. Divine representations of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—three of the seven planets known in antiquity—are depicted alongside specific signs of the zodiac. These associations between planets and zodiac signs are examples of an astrological concept known as exaltation, or hypsoma in Greek, which holds that the planets’ connections with particular zodiac signs have an impact on the human condition. Ancient astrologers believed that the planet Mars had its exaltation in Capricorn. Thus, the deity personifying Mars is depicted as a war god standing atop the sign for the fish-tailed goat Capricorn.

A mystifying aspect of the zodiac ceiling bay is its depiction of six of the Seven Arrows, messengers of female deities such as Sekhmet, the goddess of disease. “Depictions of the Arrows are not common, though we have dozens of attestations of them in Greco-Roman sources,” says Leitz. “They were mostly considered dangerous. But Sekhmet, for example, also had healing effects, so the Arrows could perhaps have had a beneficial role.” Conservators have revealed previously obscured inscriptions that contain the Arrows’ names. An inscription above the First and Second Arrows, for instance, dubs the second messenger “who steals the heart, who loves one.” It is unclear what astronomical significance, if any, the Arrows had in ancient Egypt.

Conservators working at Esna’s temple of Khnum continue to clean the scenes on the pronaos’ inner walls as well as the columns along its facade. “Now this vivid decoration can be studied in combination with the temple’s architectural layout, something that could not have been attempted until recently,” El-Leithy says. Leitz and von Recklinghausen suspect there are many more connections between the positioning of texts and images that have yet to be discovered. “I’ve been quite astonished at the numerous cases of these interactions,” says Leitz. “I didn’t expect it, and, at the moment, we don’t know whether this might have been repeated in any other temple in Egypt.”

The researchers have, however, found precise parallels between the myriad texts and images within the pronaos and those in other temples. These connections provide insight into how the priests of Esna’s temple of Khnum devised and executed the overarching plan for the decoration of the hall. Parts of the text on the exterior walls, for example, also appear in the Ptolemaic temple of Horus in the Upper Egyptian city of Edfu. This is evidence, von Recklinghausen says, that priests selected and adapted texts and representations of gods, stars, and other religious and astronomical iconography from a shared source that is now lost. “They seem to have had master pattern books with illustrations, vignettes, and all the texts, but the priests were able to use them very freely,” he says. “These were texts you could use, but you didn’t need to stick to them.” It has taken six years for the team led by Leitz and El-Leithy to clean the temple of Khnum’s extraordinary entrance hall. Throughout the process, they have recovered a dazzling array of images depicting different facets of Egyptian theology. Just two of the pronaos’ walls and the six columns lining its facade remain to be cleaned, which Leitz estimates will require about a year and a half. It remains to be seen what marvels lie hidden beneath the centuries of soot.

Slideshow: Restoring the Colors of Esna

Centuries of soot and dirt once covered the decoration inside the entrance hall to the temple of Khnum in Upper Egypt's city of Esna. Since 2018, a team of conservators from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, in collaboration with the University of Tübingen, has cleaned the hall's ceiling, columns, and walls, revealing the vivid colors of painted reliefs as they would have looked in antiquity.