When Lucas Asicona, a farmer and local historian living in the small city of Chajul in Guatemala’s western highlands, decided to renovate his three-room adobe house in 2003, he could hardly have expected to make a major artistic discovery. In one of the rooms, which contained a kitchen and several beds, fragments of plaster had been falling off the walls, revealing patches of paintings underneath. As Asicona removed more plaster using a machete, he was stunned to find a tableau covering three walls. The artwork featured a range of people dressed in outfits that mixed elements associated with both the Spaniards, who colonized the territory in the early sixteenth century, and the area’s Indigenous Ixil Maya. Researchers have come to recognize that the murals uncovered in Asicona’s house, as well as in a number of other residences in Chajul, are the product of a complex cultural amalgamation that took place in the city after the Spaniards arrived.

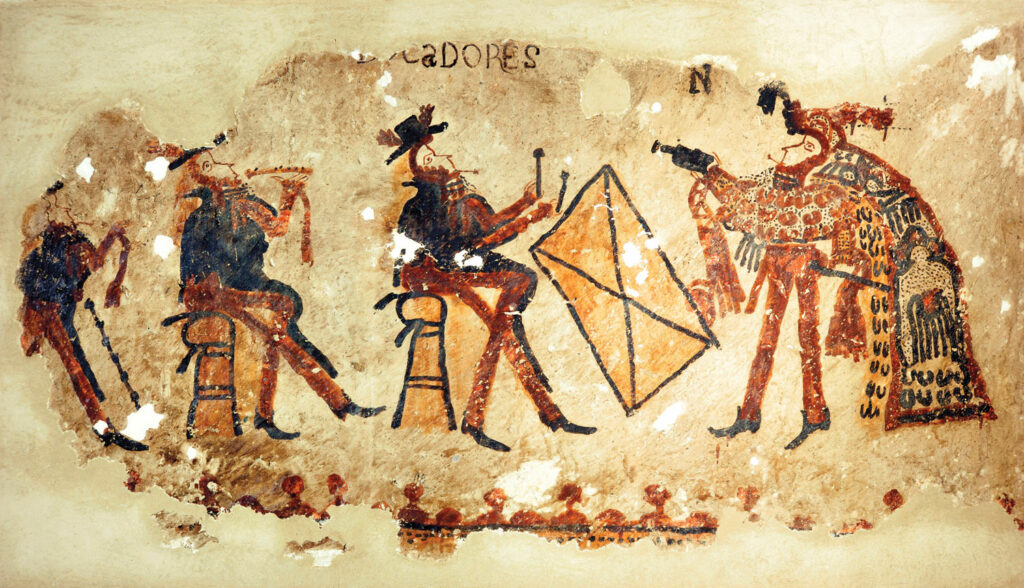

On the room’s western wall is a pair of seated musicians. One plays a short instrument, likely a flute or chirimía, an oboe-like woodwind introduced by the Spanish; the other beats a large rectangular drum. The musicians are trailed by a person who might be a dwarf carrying a long stick and they face a man who appears to be dancing while holding out a green bottle. The dwarf and the musicians wear typically Spanish attire—broad-brimmed hats, short mantles over one shoulder, caftans with puffed sleeves and ruffs, broad belts, slim trousers, and heeled shoes with pointed toes. By contrast, the dancer wears an outfit that blends Spanish trousers and heeled shoes with festive accoutrements associated with the Ixil Maya: a tasseled mantle made of feathers, a shirt with dangling strings, a long cloak sporting a representation of a white bird, and a decorative headdress.

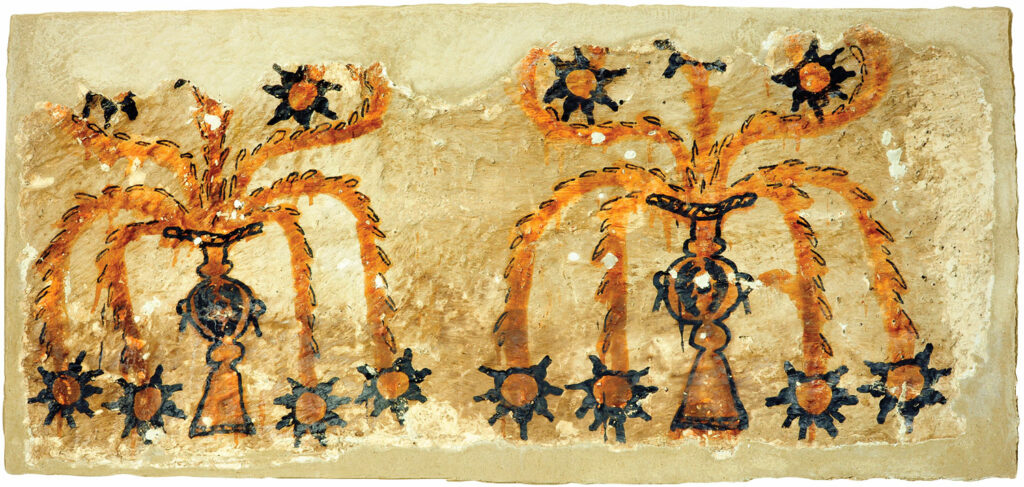

This procession continues on the northern wall, which depicts 10 people, including five dancers wearing hybrid Spanish-Maya attire and two dwarfs wearing Spanish clothing and carrying long sticks. Another three men sit on chairs holding large, curved objects that may be trumpets made from gourds. These individuals sport headdresses adorned with horns or antlers as well as caftans, mantles, and trousers that are orange with black spots. Their pants resemble the jaguar pelts commonly worn by pre-Hispanic Maya kings. The eastern wall includes two panels, each depicting a pair of vases with seven flowers at the end of long stems with tiny leaves.

Asicona informed Guatemalan authorities of his discovery, and a few researchers traveled to Chajul, which is high in the Cuchumatanes Mountains, to document the paintings. But it wasn’t until 2015 that a team led by archaeologist Jarosław Źrałka of Jagiellonian University began to intensively study and conserve the murals. “When I first saw the paintings, I was really struck because I had never seen anything before that was comparable in terms of style, subject, or context,” says Źrałka. “On one hand, you had these amazing wall paintings, and, on the other hand, people were living alongside them.” While conserving the murals, the team found that similar scenes had been repainted on the walls seven times, and that the version Asicona had revealed was the earliest layer.

With Asicona’s assistance, researchers learned of eight other homes in Chajul that have wall paintings. Several of these also include multiple layers that each depict combinations of dancers, musicians, and vases containing flowering vines. None of these paintings are as well preserved as those in Asicona’s house, though the team was able to study and conserve murals in two additional homes. They also uncovered drawings and photographs from the late 1960s to early 1970s of paintings in a residence that no longer exists. In addition to dancers and musicians, the murals there featured two women, a hunter shooting a large animal with a rifle, and a person with a feathered hat and a protruding beak-like object who earlier researchers believed represents a hummingbird.

Based on radiocarbon dating of organic material in bricks from the three houses they have studied most closely and the style of the musical instruments depicted in the murals, Źrałka thinks the paintings in these houses date to the seventeenth or eighteenth century, during the Spanish colonial period in Guatemala (1524–1821). Analysis of pigments from these houses conducted by María Luisa Vázquez de Ágredos-Pascual and Cristina Vidal-Lorenzo of the University of Valencia has revealed that their chemical composition is similar to those used in the region before the Spanish invasion, suggesting that the paintings were made by Indigenous artists. Because colonial-era paintings in Guatemala tend to be found in churches and convents, not private homes, the murals’ domestic location distinguishes them as particularly novel. “In most cases you have scenes related to Christianity,” says Źrałka. “Even though the paintings were painted by Indigenous people, you have representations of Christian paradise, of Christian hell.” The Indigenous artists who used the homes in Chajul as their canvas were clearly trying to capture something quite different. Determining just what they were attempting to express required digging into Chajul’s history and exploring the ways in which its Indigenous residents maintained their traditional culture while ostensibly adopting Christianity.

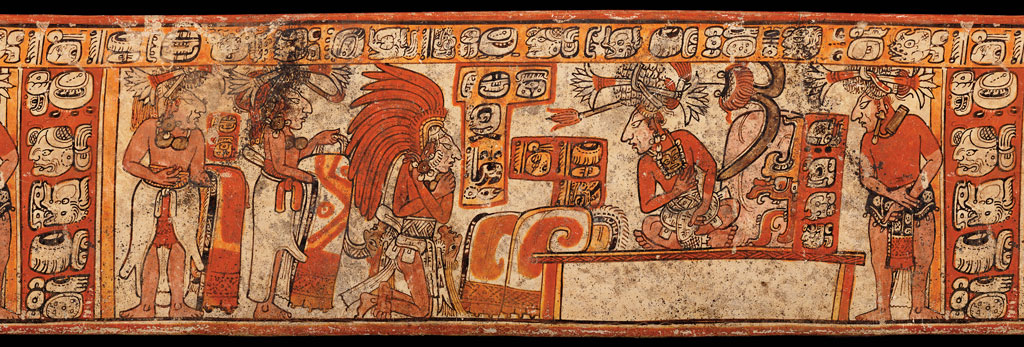

The earliest clear archaeological evidence of settlement in Chajul, including a tomb excavated in the late 1950s or early 1960s, dates to the Maya Late Classic period (ca. a.d. 600–800). Chajul appears to have been an important political entity with its own dynasty of rulers at this time; glyphs on a vessel from the area identify its owner as a guardian of the king of Chajul. The vessel’s illustrations include a kneeling figure who may be the Chajul king wearing a feathered headdress and a belt with two human heads attached as war trophies. Prior to the Spanish invasion in the early sixteenth century, Chajul and the other lands of the Ixil Maya were subjugated by their more powerful neighbors to the south, the K’iche’ Maya. The Spanish conquered the Ixil in 1530. Some two decades later, they forced the residents of 11 Ixil communities in the surrounding area to move to Chajul, where they would be easier to control. These people were settled in neighborhoods that corresponded to the names of their original villages. Similar forced relocations concentrated the Ixil in two other cities, Nebaj and Cotzal.

Dominican missionaries set out to spread Christianity to the Ixil, though they had a relatively limited presence in the area. The region’s rugged, mountainous terrain was difficult for the Spanish to navigate. In 1690, more than a century and a half after the Spanish conquest, Guatemalan-born Spanish chronicler Francisco de Fuentes y Guzmán described Ixil territory with typical colonial disdain as cold and hostile, the Ixil language as exceedingly difficult, and the denizens of Chajul as “wild and rustic” sorts who spent their time in the forest hunting quetzal birds for their feathers. Around the same time, a Dominican official in Guatemala reported that the road to Chajul was dominated by thick forest and that walking on it was like “swimming in complete mud.”

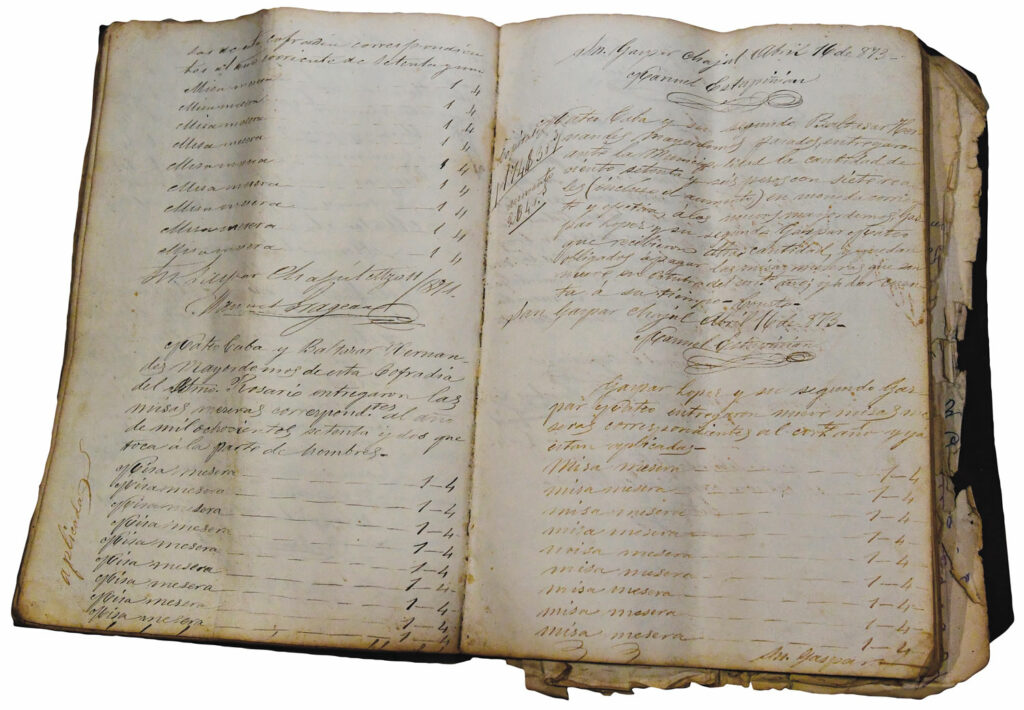

The colonists did, however, establish organizations called cofradías, or “brotherhoods,” to encourage the local Maya to worship Catholic saints. Each cofradía was charged with caring for a wooden sculpture representing one of the saints, but the organizations came to blend traditional Maya rituals and ceremonies with Catholic worship. “Although cofradías were started as an imposition, the Maya quickly found a way to transform and rearrange these Catholic institutions into something that expressed the Maya worldview,” says Victor Castillo, an archaeologist at Jagiellonian University who is originally from the city of Huehuetenango, also in Guatemala’s western highlands. “It has been documented ethnographically that many cofradías used the traditional 260-day Maya calendar to schedule and perform rituals, and that during rituals devoted to the feasts of the saints, members of the cofradías visited sites that Maya communities considered sacred.” In recent years, Chajul’s surviving cofradías have joined together to form a single committee dedicated to preserving evidence of traditional practices.

The festivities organized by the cofradías once included elaborate dance plays that involved extensive preparation and boisterous performances accompanied by copious consumption of alcoholic beverages. These celebrations have largely faded in recent decades due to the investment of time and resources necessary to put them on. In A New Survey of the West-India’s, or The English American His Travail by Sea and Land, Thomas Gage, a Dominican friar who traveled in Guatemala in the early seventeenth century, describes, with some derision, the preparation and performance of one such dance:

For the better part of these two or three months the silence of the night is unquieted with their singing, their holloaing, their beating upon [drums and using as trumpets] the shells of fishes….And when the feast cometh, they act publicly for the space of eight days what privately they practiced before. They are that day well appareled with silks, fine linen, ribbons, and feathers according to the dance. They begin this in the church before the saint, or in the churchyard, and thence all the octave, or eight days, they go dancing from house to house, where they have chocolate or some heady drink or chicha given them. All those eight days the town is sure to be full of drunkards. If they be reprehended for it, they will answer that their hearts rejoice with their saint in Heaven, and that they must drink unto him that he may remember them.

As researchers studied the murals in Chajul and spoke with residents, they learned that the houses all have current or past associations with leaders, or mayordomos, of cofradías. The paintings, they came to believe, depict dance plays put on by the organizations. Notably, the faces of all the people in the murals are rendered with a few brush strokes and lack individuality, as if they are wearing masks. In addition, the repetition of similar characters such as the dancers and the dwarfs suggests that the murals represent a narrative. The researchers believe that the dances took place in the very rooms with the paintings, as well as on the houses’ patios, in churches, in the town plaza, and even in cemeteries. Gaspar Ramírez, a former cofradía member and owner of one of the houses with wall paintings, shared his memories of the dance plays in 2021, when he was 95 years old. “He said that when he was a member of the cofradía, when he was younger, they danced inside his house,” says Źrałka, “and then the dancers moved outside and were dancing on the patios.”

In Asicona’s house, as in almost all the Chajul houses that have murals, the paintings of flowering plants flank altars that include crosses and other elements of Catholic iconography. This is a continuation of a practice that began during the colonial period, when the sculpture of the saint to which a given cofradía was devoted would be placed atop an altar in the house belonging to its mayordomo. Every year, each cofradía would choose a new mayordomo, and the saint’s sculpture would be moved to the incoming leader’s house.

The mayordomo’s house was a locus of activity during a packed season of Catholic and Maya ritual observances from late December to early January. Leading up to this time, the cofradías prepared at length to perform dance plays, overseen by a Maya ritual specialist called a mama’. This included pilgrimages to sacred places, in particular several hills called Tz’unun Kab’ located between Chajul, Nebaj, and Cotzal. Christmas occurred during this period, as did the annual feast of Chajul’s patron saint, Saint Caspar, one of the three wise men who visited the baby Jesus. On January 15, after several weeks of dance plays, a Maya celebration called mak’xeb’al b’ixal, or “end of the dance season,” was held.

Researchers believe that, when a new mayordomo was installed, new murals would be painted in his house. Thus, the layers of murals in several of the Chajul houses likely represent different times when their residents served as mayordomos. “This is great archaeological evidence of this constant cycle of moving the figure of the saint, moving the seat of the cofradía to a different place, and then redecorating the house for the tenure of the new mayordomo,” says Castillo.

In addition to exploring the ways in which cofradías combined Catholic and Maya practices, the researchers have tried to determine which of several different dance plays known from historical and ethnographic sources to have been performed in Chajul might be depicted in the wall paintings. Monika Banach, an anthropologist at Jagiellonian University, has interviewed residents to learn what they think. One of the most common answers they have given is the Baile de la Conquista, or Dance of the Conquest, which dramatizes the invasion of Guatemala by the Spanish, focusing on Tecún Umán, the heroic leader of the K’iche’ Maya, and his death. According to Castillo, this dance features many elements of traditional Maya culture and religion, including a prominent character who is a seer. However, he thinks that the Dance of the Conquest was only performed starting in the mid-nineteenth century, in the context of Guatemalan nationalism after the country gained independence from Spain. Thus, Castillo says, it’s unlikely the murals depict this particular dance play.

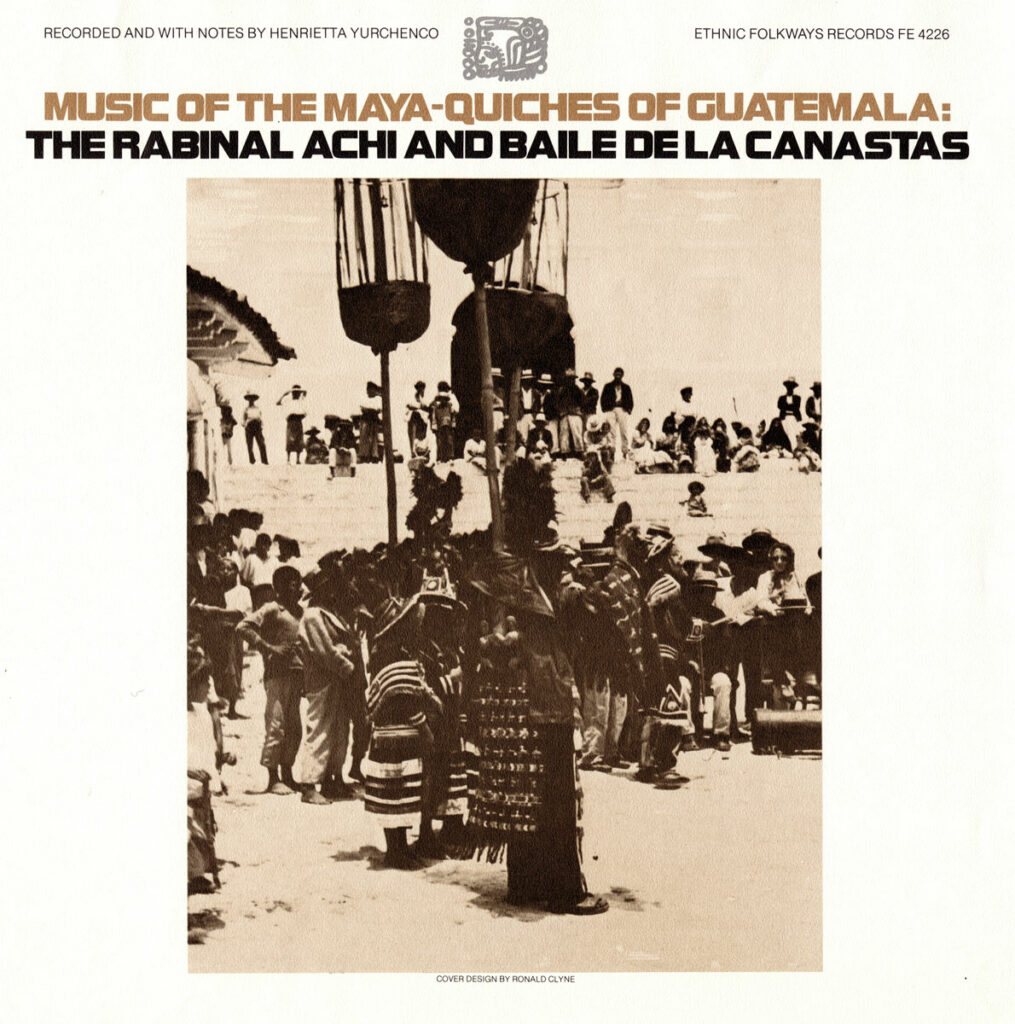

A tantalizing possibility for Banach is that the murals in Chajul portray the Tz’unun, or Hummingbird Dance. She considers this celebration a strong candidate because some of the wall paintings prominently feature female dancers facing the viewer, and the Tz’unun is one of the few dance plays known to have been performed in Chajul that included women as central characters. Banach also suggests that the bird depicted on the cloaks of the dancers in the murals might be a hummingbird drinking nectar from a flower. The dance, which is believed to predate the arrival of the Spanish, is fondly recalled by present-day residents of Chajul, although they say it has not been regularly performed in the city for nearly 75 years. In 1945, American ethnomusicologist Henrietta Yurchenco made an audio recording of the Tz’unun being performed in Chajul, which was released on vinyl.

On one level, the Tz’unun is the story of a young girl named Marikita and her suitor, Rey Oyeb’ Achi, who appears as both a man and a hummingbird. Marikita’s father, Mataqtani, desperately attempts to thwart the match. On another level, it is a creation story—Marikita is a weaver who, by the act of weaving, creates elements of the world such as people, maize fields, rainbows, and mountains. Later in the story, Mataqtani inadvertently kills Marikita with a lightning bolt, breaking her into parts that go on to form the world’s animals.

Banach notes that various characters in the Tz’unun correspond to locations in the sacred Maya landscape. “The figure of Rey Oyeb’ Achi in the Tz’unun narrative can correspond to an Earth being,” she says. “It’s a mountain called Ju’il, a sacred entity that everyone in Chajul knows about.” Along with a mama’, cofradía members traditionally hold gatherings called komon saqb’ichil, or “community dawn ceremonies,” at altars atop archaeological remains on this mountain, which is located just north of Chajul. These kinds of ceremony marked the beginning of the Maya year and the different stages of the maize planting season. Banach says that this same Earth being is identified with Saint Caspar, underscoring the complex ways in which the Ixil melded their traditional worldview with Catholicism. “People continue to tell the story of Marikita and Rey Oyeb’ Achi over the fire,” she says. “They will say, ‘This is the real history of Chajul.’”

The murals may capture long-ago performances of the Tz’unun, or, perhaps, other dance plays once presented in Chajul. For Castillo, the illustrations have the power to bring the dances to life in a way that written records do not. “I had read descriptions of the dances of the colonial period and descriptions of the costumes and garments worn by the dancers,” he says. “But now I was watching them. They were right in front of me. For me, seeing the paintings was a revelation.”