A shipwreck in the South China Sea advances China's emerging field of underwater archaeology

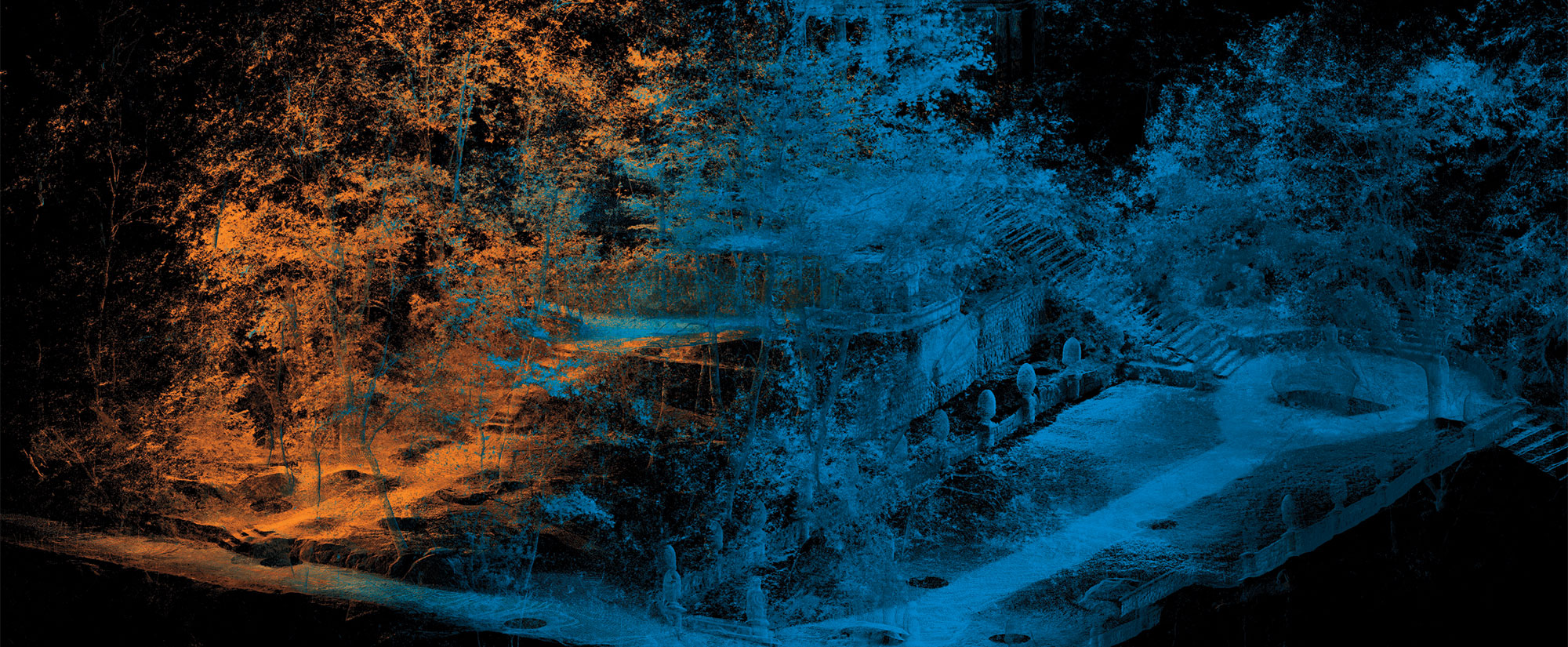

(Courtesy Cui Yong)

Just off the coast of the southern Chinese island of Nan'ao, on a boat called the Nan Tianshun, Chinese archaeologist Cui Yong is the only still thing on deck. He sits near the front of the repurposed barge, leaning into a radio receiver while everyone else on the boat bustles around him. Researchers in wetsuits and fins splash into the water. Workers shout back and forth, pulling on taut ropes that disappear into the ocean. Someone hoses down a row of oxygen tanks. Loud as they are, these on-deck activities barely seem to register with the archaeologist. His attention is 90 feet down, on the bottom of the South China Sea. The radio crackles with reports from his divers on the wreck of a Ming Dynasty pirate ship.

Named the Nan'ao Number One, the wreck that Cui is excavating lies along a stretch of ocean that Chinese historians regard as the country's "Marine Silk Road." During China's heyday as a maritime power during and shortly after the Song Dynasty (A.D. 960-1279), the route was popular with traders but prone to dangerous storms, resulting in a trail of sunken ships. The Nan'ao wreck is part of an abundant record that has helped speed the development of Chinese underwater archaeology, a discipline with barely 20 years of history in the country, and encouraged a frenzy of new underwater excavations.

In this litter of wrecks the Nan'ao Number One is unique. It is the only known wreck from the late Ming Dynasty. Archaeologists estimate the ship sailed between 1573 and 1620, a period when China had turned inward, banned maritime commerce, and begun to dismantle its once-great fleets. In another time, the vessel would have been a merchant ship, following a busy trade route. But when China closed its shores and docks, maritime trade and commerce became piracy and smuggling. Officially, the Nan'ao ship never should have been in the water—it was likely moving along the coast illegally. Its cannons, now half-buried in the mud at the bottom of the South China Sea, would have been necessary for defense.

The Nan'ao ship is a rare find, but its fate is a familiar one in this part of the ocean. "This is a dangerous passage," says Cui. As the boat snuck along the coast, something, whether bad weather or hidden rocks, caused it to sink and deposit its load of contraband—ceramics, copper coins, and ironware—onto the sea floor. "The weather can be bad," Cui says as the wind picks up around his own boat. "And, over there, there are rocks you can't see."

The excavation of the Nan'ao and tales of a Ming Dynasty pirate ship have lured a rotating cast of journalists to the excavation site. Cui has grown accustomed to the attention. At 49, he is one of China's first generation of underwater archaeologists and, with a run of high-profile wreck discoveries, he is the most recognizable face in an ascendant discipline. On the deck of the Nan Tianshun, however, Cui is soft-spoken and at home in flip-flops. Only the flecks of gray in his hair betray his age and, perhaps, the stress of his job, he says. Wrecks like the Nan'ao, he adds, help attract media and increase government funding. But the increased exposure also attracts looters and adds pressure. It is a delicate balancing act that is visible in the commotion on the Nan Tianshun. Journalists in deck shoes pick their way carefully through stacked oxygen tanks, while border patrol officers in fatigues and orange life jackets stand at attention at the corners of the boat. "The government is giving us money to do the excavations, so we should be able to show people the progress we are making," Cui explains. "Archaeologists have to learn how to juggle these things."

(Courtesy Cui Yong)

With few experienced underwater archaeologists at work in China today, Cui has become an excellent juggler. He was still working on a previous find when he first heard reports from Nan'ao Island in 2007. Some local fishermen were pulling Ming Dynasty porcelain out of the ocean. "I knew it was a wreck," Cui says. "There were so many artifacts from the same period being taken from the same spot in the ocean." When he arrived at the island and made his first dive, the Nan'ao site proved better than he had imagined. The wreck was unusually well preserved and the conditions were good for excavating. It was deep, but the water was clear and the mud at the bottom of the ocean soft and manageable. "I got lucky," he says.

Cui's excavation team was given permission to begin digging two years ago, and since then he has spent as much time as weather permits floating above Nan'ao Number One. After one excavation season, nearly half the wreck is exposed. The top decks have been worn away, but its belly lies undisturbed, oriented along a northnsouth line. Two curves of wood are exposed toward the stern, hemming in rows of porcelain bowls, platters, and cups, many still stacked neatly. On excavation maps, archaeologists have filled in where they speculate the sides of the boat continue, and they estimate the Nan'ao runs around 90 feet from bow to stern.

The Nan'ao sank at the mouth of a particularly dangerous stretch of water. It sits at the northern edge of present-day Guangdong Province, near the entrance to the strait between the coasts of China and Taiwan. Typhoons frequent this passage and could blow ships—Ming Dynasty pirate vessels and excavation barges alike—into hidden rocks or smash them along the coast.

Excavations at the site move painstakingly slowly. Because of the depth of the site, around 90 feet down, a diver is only allowed 25 minutes at the bottom and only one dive a day. If a storm hits, or if the wind is simply too high, no one dives. This, says Cui, generally rules out fieldwork nine months of the year. And even on good days, he is concerned for the safety of his divers. They descend in pairs and keep close tabs on bottom time. Cui is quick to point out one of the Nan Tianshun's key features—a decompression chamber.

Despite the challenges, Cui's team is making progress. "Last year was a good year," Cui says. "We had a full 100 days to excavate." During that time, he says, the archaeologists retrieved more than 10,000 pieces of porcelain from the sea floor. This year he hopes to retrieve all the remaining pieces from the ship's stores.

(Courtesy Cui Yong)

The fact that the Nan'ao wreck has any artifacts at all is testament to the determination of Ming Dynasty businessmen. Boats caught defying the ban on maritime trade could be scuttled and their crews thrown in jail. These deterrents did not keep the Nan'ao merchants down—they simply became smugglers. "The ban was regularly ignored in southern China," says Wu Chongming, a colleague of Cui's who teaches at the Maritime Archaeology Research Center at Xiamen University in Fujian. Some historians theorize that the ban on international trade was originally intended to starve increasingly bold Japanese pirates. Rather than give up the business, Chinese merchants turned to piracy themselves—both smuggling and raiding. The Chinese still called smugglers and raiders wokou, a derogatory term for Japanese pirates, but just a few years into the ban, Chinese pirates had taken over the South China Sea. "There is a saying in Chinese," says Wu. "When the market closes, all the businessmen become smugglers."

The pieces Cui's team are bringing up were likely not the most valuable items onboard, explains Cui. They were probably, in fact, an afterthought for the Ming Dynasty smugglers. "It was probably ballast," says Cui. Other cargo, such as tea or the strings of copper coins that have been found on the wreck, would have been the ship's real treasure. The archaeologists have uncovered some organic material, Cui says, but haven't subjected it to testing yet. Though they didn't hold much monetary value then, today the porcelain pieces are priceless for determining the origin and probable destination of the ship.

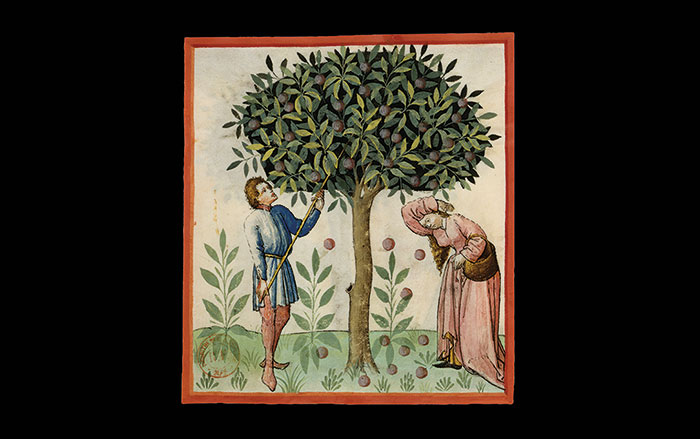

As soon as Chen Huasha, a researcher from the Beijing Palace Museum, arrives for the field season, the crew of the Nan Tianshun pulls out crates of porcelain for her to sort through. She sifts carefully through the blue-and-white pieces, each covered with glazed flowers, animals, and human figures. Chen, who has spent time on the Nan Tianshun for two years running, believes the bulk of the porcelain uncovered comes from kilns that were operating in China's Fujian and Jiangxi provinces. When asked how she can tell, Chen says, "There are characteristics."

Chen selects a large dish that shows a woman plucking a flower. The round dish, she explains, represents the moon, and the woman standing at its center is Chang'e, the moon goddess in Chinese folklore. The flower, she says, could have to do with success at an imperial examination, a process that was called "picking flowers" at the time. Later, Chen pulls out a dish decorated with the figure of a woman with a bouffant hairdo. "Her hair looks like a flower," Chen says. "This was fashionable among royal women during the late Ming Dynasty." The subjects on the porcelain are so characteristically Chinese that Chen suspects they were intended for other Asian markets, such as Japan or the Philippines.

In addition to its porcelain, Nan'ao Number One stands out for its weaponry. Xiamen University's Wu stops by the Nan Tianshun to visit Cui and see for himself the Nan'ao's bronze cannons, which still wait on the ocean floor. "This is the first boat found with cannons on board," he says. They could have been used to protect the smugglers from imperial forces. "They would confiscate your goods, put you in jail, and sink your ship—the stakes were high." The cannons could also have served to protect the boat against other pirates or raiders. The sailors might also have feared becoming entangled in the intermittent battles that occurred between the Dutch and Portuguese through the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth.

(Courtesy Cui Yong)

While the Nan'ao ship stands out for having sailed outside the law, underwater archaeology in China has its own set of pirates and lawbreakers. Cui and Wu are both at the forefront of a young profession—before they started their studies in 1988, China had no trained underwater archaeologists and wrecks like the Nan'ao were the exclusive territory of treasure hunters. Fortunes may have been made among fishermen.

One treasure hunter in particular caught the attention of China's government and was instrumental in forcing the country to consider its own underwater excavations. Cui is a bit chagrined by it, but he explains that the development of underwater archaeology in China owes much to English treasure hunter Michael Hatcher. Hatcher's biggest find, which came to be known as the Nanking Cargo, came in the 1980s. All the archaeologists on the Nan Tianshun know the story well. It was the wreck of a Dutch ship that had run afoul of a coral reef near Indonesia in 1752, dropping a load of tea, gold, and more than 150,000 pieces of Ming Dynasty porcelain. "The porcelain was all from Jingdezhen, near Nanjing," says Wu. "That boat wasn't Chinese, but all that porcelain originated from China." China's government did its best to stop the sale of what it saw as national cultural heritage, but Hatcher was still able to auction off the bulk of his find in 1986, reportedly earning more than $20 million. Two years later, Cui was enrolled in an underwater archaeology program at Qinghua University. "Hatcher got Chinese archaeologists to start studying underwater excavation techniques," he says.

(Courtesy Cui Yong)

Cui and Wu often refer to their first experience with underwater archaeology as the "Australian Program." Qinghua partnered with Adelaide University in Australia, and the first class of underwater archaeologists was selected on the basis of physical fitness as much as anything else. "They needed young archaeologists, and I was in good health," Cui says. "And, of course, the other point was that

I could swim."

The first decade of underwater archaeology went slowly, but the last two boats on which Cui has worked have sped that development up considerably. In 2001, Cui was sent to head excavations at Nanhai Number One, the wreck of a Song Dynasty boat that sailed well before the dismantling of China's fleet during the Ming Dynasty. "[The Song Dynasty] was a time when China's sailing fleet was well developed," Cui says. "Chinese boats were making it all the way to India and Africa." The boat was discovered by accident in 1987 by a team of English and Chinese researchers who were searching for an English boat thought to have gone down in the area. The Chinese archaeologists, however, weren't prepared to take on the large and complicated excavation.

"The Nanhai was in shallower water than the Nan'ao, but the visibility was terrible," Cui says. "We would have had to conduct excavations by feeling our way along the bottom of the sea floor." In 2001, archaeologists revisited the wreck with a bigger budget—$20.3 million—which was used to build a custom saltwater tank on Hailing Island in Guangdong, part of a new Maritime Silk Road Museum, which opened in 2009. Archaeologists actually lifted the boat—along with the silt in which it was buried—out of the ocean and into the tank for study. The spectacle of a 3,000-ton steel cage being pulled out of the water earned shipwrecks a place in China's popular consciousness.

(Courtesy Cui Yong)

"These boats—two very different boats—have attracted a lot of popular interest for marine archaeology," says Cui. "Without them, I don't think it would be growing so quickly [in China]."

The frenetic activity on the Nan Tianshun is a sign of how far underwater archaeology has come since Cui took his first diving class. The Chinese government continues to invest in digs and soon the Nan Tianshun will be replaced with an updated excavation vessel. But the interest in the Nan'ao wreck has also put all of China's wrecks in greater danger. The biggest threat to underwater archaeology, Cui says, is the popularity of the artifacts such sites carry. Unblemished, authentic Ming Dynasty porcelain can command high prices from collectors, and thieves have learned to target sunken ships to find it.

According to the archaeologists at Nan'ao, keeping the wreck well protected has been the key to their success. However, they are on-site only a few months a year. The rest of the time, Nan'ao Number One is under the watch of one determined local law enforcement officer. "If we had no Zhu Zhixiong, we would have no Nan'ao," Cui says.

Zhu, or Chief Zhu, as everyone on the boat calls him, is the head of Nan'ao Island's maritime border control. He is perpetually in uniform and has a tendency to stare, earnest and unblinking, when speaking about the Nan'ao. "When the fishermen uncovered the porcelain they wanted to keep it," he says. They discovered the Nan'ao's treasures while diving off the coast of the island in 2007 and set about building their collection in secret, hoping to attract the attention of a buyer. Instead, tales of the stash reached Zhu. "We run a program where we reach out to the local people and they feel comfortable talking to us," Zhu explains. "Somebody came to us and told us about the artifacts." The border patrol confiscated the porcelain and Zhu did his best to explain to other fishermen that retrieving and selling the artifacts is against the law.

"We didn't do this for glory," Zhu says. "We didn't know what was down there at that point. We don't dive, we can't see under the water, but we know it is important to protect our national heritage." Zhu dedicated himself to guarding a wreck he couldn't see.

"This isn't just a Chinese problem," Zhu says carefully. "But thieves and treasure hunters are tireless." At the Nan'ao wreck, Zhu set up 24-hour surveillance. "They will come at night or in bad weather, thinking you won't chase them. Some of them are very professional." Some haul in diving gear and lights. Others are fishermen and experienced enough in the water to free dive 90 feet to the bottom. "One boat must have studied our habits and came in through an area we weren't patrolling. When we came with our boats they fled, but we saw, with complete clarity, where they were headed." Zhu's team called ahead to another guard base and caught the thieves.

Over the years, Zhu's reputation has spread. Patrol officers say they are seeing fewer attempts every year. Still, says Zhu, you have to be vigilant. "You can't sleep if you want to protect our heritage," he says. When Cui sees him on the deck of the Nan Tianshun, he gives him an affectionate pat on the shoulder and says, "Every wreck needs its own Chief Zhu."

Cui considers himself lucky to have such a dedicated protector. In many areas of the South China Sea, archaeologists hesitate to explore new wrecks for fear that even a preliminary dive will attract the attention of looters. Despite Zhu's vigilance, the persistence of thieves and vulnerability of the wreck add to the pressure on the archaeologists on the Nan Tianshun. "We are hoping to finish bringing up artifacts this year and look more closely at the structure of the boat," Cui says. Archaeologists have identified the bow, stern, masts, cargo cabin, and possibly anchor. "Maybe we'll be able to bring the whole thing up; we're not sure yet."

Once finished at the Nan'ao, Cui says he might take a break from excavation. His colleague Wu, however, is enthusiastic about future excavations on the coastline north of the Nan'ao in Fujian Province. Here, says Wu, will be the cradle of Chinese marine archaeology. The Nan'ao Number One and the Nanhai Number One are just two examples from a sea rich with history and prone to sinkings. "There are thousands of wrecks," he says. They've barely broken the surface.

Lauren Hilgers is a freelance writer based in Shanghai.