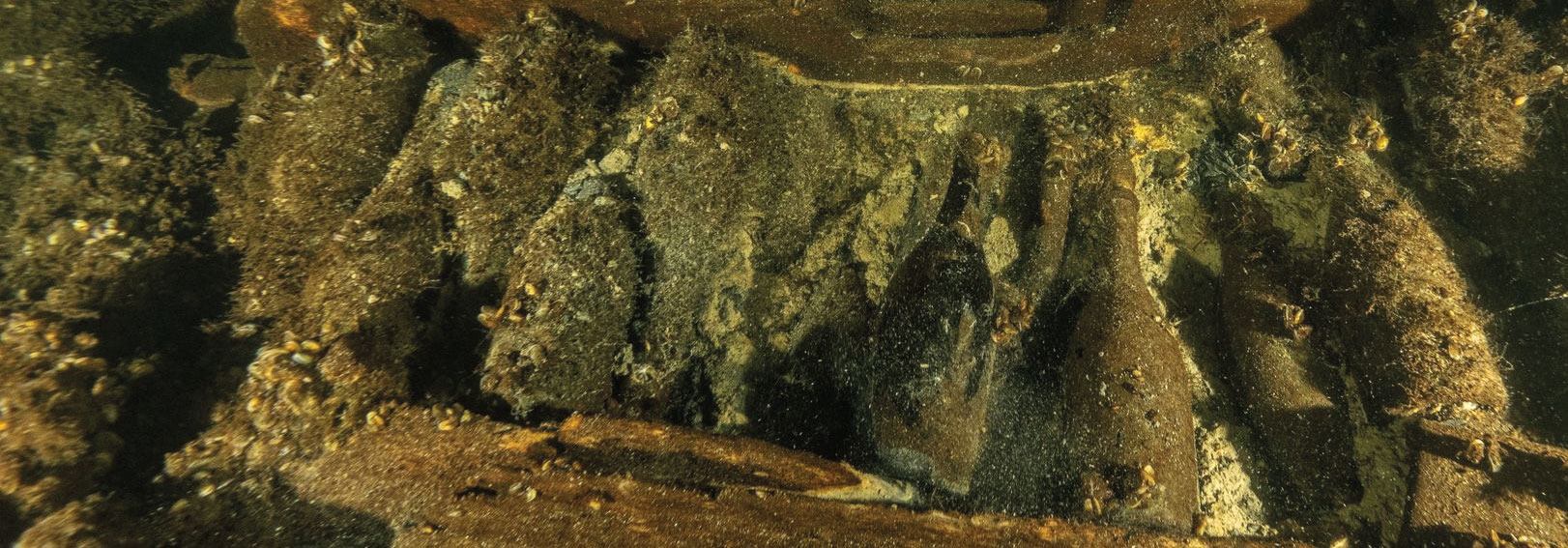

(Courtesy Finding Sydney Foundation)

The loss of the HMAS Sydney (II), pride of the Australian navy, has long been a source of pain and bewilderment. In waters off Western Australia in late 1941, following a successful tour in the Mediterranean, the Sydney encountered a ship claiming to be a Dutch freighter—actually the HSK Kormoran, a German raider that had menaced merchant ships for months. As the Sydney approached, the Kormoran opened fire, crippling the more powerful ship in minutes. Both ships sank, but most of the Kormoran crew survived and were captured, while the Sydney and its 645 sailors were gone without a trace.

Amid public disbelief and distrust of the German account of the battle, "thoughts turned to treachery to explain the loss," says Glenys McDonald, director of the nonprofit Finding Sydney Foundation (FSF). Official inaction and the inability to agree on a search area prevented serious attempts to find the wrecks. In this vacuum, many conspiracy theories arose, accusing the Germans of illegal ruses and executions, and the Australian government of a cover-up. A proper search was finally mounted by FSF in 2008. Despite bad weather and technical mishaps, the expedition found both ships within two weeks, 14 miles apart in 8,000 feet of water. "For the relatives of those lost in the action, the significance of this cannot be overstated," says John Perryman, senior naval historical officer at the Sea Power Centre - Australia.

Archaeologically, the locations of the wrecks and their damage support the long-disputed German accounts. As the survivors said, the Sydney was struck by a torpedo near a forward turret and suffered heavy shell damage to both sides. Evidence of rapid sinking helps explain why there were no survivors. An official commission has determined that all archaeological evidence confirms that there were no underhanded tricks or war crimes committed. "For underwater archaeology to have attended to a running sore on the Australian psyche is very important," says University of Western Australia maritime archaeologist Mack McCarthy, "proving that you can learn from archaeology an awful lot about what happened, even in World War II." A nation seeking closure found answers—but not to every question. It will never be known why the more powerful Sydney approached an unknown vessel, forfeiting its superior range and firepower. "What thought processes were taking place on the compass platform of the Sydney will never be known for sure," says Perryman.