It’s just after lunch on a chilly November afternoon in a fifth-grade classroom in the Soundview section of the Bronx. With the radiators blasting heat, this is the time when the 29 students might be inclined to nod off. But today, the room is alive with expectant chatter as they unseal ziplock bags and unwind layers of bubble wrap to reveal artifacts from a recent archaeological dig in Brooklyn.

Armed with an array of plastic calipers, rulers, and magnifying glasses, the students break off into small groups and begin to examine and measure the artifacts with the goal of identifying what they were once used for. The activity is part of a New York City Department of Education urban archaeology program I have helped administer for the past three years, which allows public school students to learn about the city’s history through actual artifacts. The program was funded by a federal Teaching American History grant, and its materials were developed by a team of teachers, curriculum writers, and New York City archaeologists.

This particular afternoon, I sit behind a group of four students and listen in as they work their way through a series of questions about one of the artifacts. Their teacher has provided each of them with an “artifact analysis template” to fill out, and the only information they’ve been given is that the object they are handling belonged to someone who lived in New York City five generations ago. Just as is sometimes the case in archaeological fieldwork, the students initially examine artifacts without the benefit of much context or background. That doesn’t deter them at all.

How wide is it? “About an inch,” states Marco [editors note, the students' names have been changed].

“One and an eighth inches exactly,” Rita corrects softly.

How tall is it? “Same thing, one and an eighth inches,” Mee says with just a hint of puzzlement.

“It’s square!” blurts out Neves, beaming.

What is it made of? “Not metal,” Marco says, striking the object against the side of his desk. He twists it hard until he grimaces and his arms shake. “It bends a little,” he announces. “Plastic maybe.”

How does it feel? “Smooth,” says Mee, running the front side over her palm. “Kind of like glass.”

“Like icing on a black-and-white cookie,” says Neves.

Their teacher walks over and smiles as she surveys the group’s progress. She leans over and whispers in Marco’s ear, “Please don’t bend the artifacts.”

“It’s a key ring,” Neves pronounces eagerly, turning the small, thin black object in his hands. But with no encouragement from his peers, he slumps back in his seat to await more fruitful suggestions. The other members of his group eagerly hold out their hands as they wait for the object to be passed to them.

“Might be a toy,” Marco opines. “See, these look like a castle,” he explains, pointing to the crenellations on all four edges of the bottle-cap-sized mystery. Noticing the slightly corroded pin and clasp on one side, he hurriedly adds, “And you pin it on your shirt.”

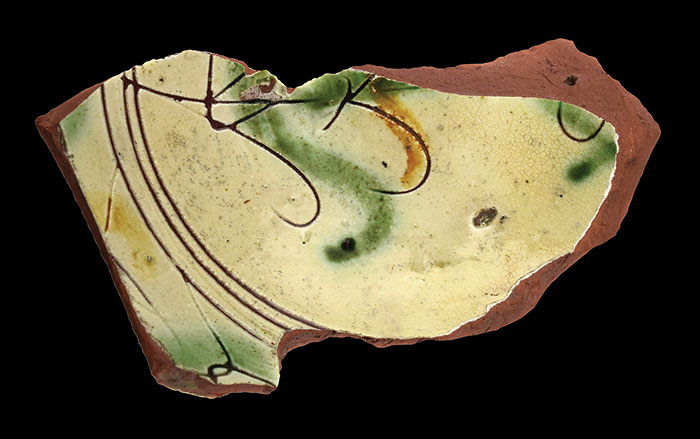

This artifact and many others were all found in a 2010 archaeological dig of nineteenth-century refuse pits in a backyard on Ten Eyck Street in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg. Before ground could be broken on a new development at the site, archaeologist Celia J. Bergoffen conducted a survey in accord with municipal and state laws. The real estate developer subsequently donated to the city boxes filled with a jumble of items from the dig, found amid broken glass, corroded metals, and ceramic sherds. From these, and from boxes donated from a dig on Jamaica Avenue in the Cypress Hills neighborhood straddling Brooklyn and Queens, we were able to salvage enough intact items to assemble four urban archaeology kits, each with artifacts sufficient for a single class.

In the nineteenth century, both neighborhoods were home primarily to Irish Catholic and German Lutheran immigrants. By the 1880s and 1890s, the Ten Eyck Street population also included Italians and German and Eastern European Jews. In the 1870s and 1880s, when municipal water pipes were laid in the neighborhoods, allowing for indoor plumbing, outdoor cisterns and privies were rendered obsolete—and potentially dangerous. Residents at the Ten Eyck Street site quickly filled these holes up with household trash. A privy at the Jamaica Avenue site was filled with trash and debris at a later date when a building was demolished.

Amid the refuse at the Ten Eyck Street site, artifacts such as a teacup with countryside scenes and a Bohemian-style red ceremonial sherry glass were found. Bluing bottles, sewing implements, a rubber comb and a wooden toothbrush handle, nursing bottles, a misshapen ink bottle, and Dutch tobacco pipes were also discovered. According to Bergoffen, many of the finds reflect “normal domestic activities of adults and children in a respectable, working-class household of the late nineteenth century.” Some artifacts, such as a metal needle, provide clues to the work many of the street’s residents did as tailors or seamstresses. Pig, chicken, and turkey bones, including the remains of complete animals, suggest that a butcher shop may have been present on the site or nearby. Shoe soles were also found in large numbers, which might indicate that some of the residents were employed as cobblers.

The Jamaica Avenue site was different because of the types of business and industry that surrounded it. In addition to residences, there were several large cemeteries in the area, so stonemasons who crafted gravestones worked in the vicinity. The area was also home to saloons, beer halls, gambling dens, and brothels, as evidenced by artifacts including a desktop bell, beer and whiskey bottles, an umbrella finial, a perfume locket, and a chewing tobacco advertisement.

Bergoffen is pleased that the artifacts she found at the Ten Eyck Street site have found a new life teaching Bronx schoolchildren what their city was like more than a century ago. “I was very happy not to see these artifacts just disappear into a box and never be seen again,” she says. “This is the history of the community and it belongs to the community.”

Peering through a dollar-store magnifying glass, Rita turns the group’s artifact over and over until she straightens up suddenly and points to the smooth circular raised surface on the front side. “I think it’s supposed to get pinned on your clothes, and you put a picture of something in the empty circle,” she says. “I wonder who wore it.”

This stage of the analysis is when teachers provide the students with a laminated information card for each artifact they have examined. The group gets answers to their many thoughtful questions. The card notes that the object was a “square black vulcanite brooch” and includes the following information:

Carefully molded and colored, vulcanite so closely imitated expensive jewelry materials in color, shape, and luster that it was often difficult to tell them apart. And more importantly, it offered the middle and lower classes an opportunity to own jewelry almost identical to that worn by the very wealthy and to participate in the fashion trends and rituals of the time.

From the mid-1800s to just before 1900, black jewelry was considered extremely fashionable and stylish, while it was also commonly used to indicate that the person wearing it was in a period of mourning for the death of a loved one. Probably, one of the main catalysts for mourning jewelry in the United States was the catastrophic loss of life during the Civil War.

The power that an artifact like this can have becomes clear as the group recalls from their study of the Civil War that New York suffered more casualties than any other state in the Union. The discussion takes on a personal cast as they wonder if, perhaps, the wife, sister, or daughter of a soldier killed in the war once wore this very brooch. Before long, the students connect the brooch to a practice they are familiar with—in some New York City cemeteries today, photos of the deceased can be seen on display at their graves. People in nineteenth-century New York seem to have led vastly different lives, but perhaps not entirely so.

In order to prepare an information card for each artifact, our team of curriculum developers conducted extensive research on the objects’ provenance. Part of this research included a visit to College Point, in Queens, where Conrad Poppenhusen, a former whalebone dealer on the Brooklyn waterfront, had built a massive hard-rubber factory and had become one of the area’s prominent citizens. Using a highly profitable patent licensed from inventor Charles Goodyear, Poppenhusen’s employees turned India rubber and sulfur into vulcanite combs, buttons, and pieces of costume jewelry, much like those found in a backyard hole on Ten Eyck Street. Over a century later, these artifacts have been dug up by an archaeologist and delivered into the hands of students in this classroom in Soundview. The dig produced a lice comb and a button, both made of vulcanite. It also turned up the mourning brooch.

As a further echo of archaeological investigation, the students’ inquiries, prompted by artifacts found in the digs, are supported by additional research. After being introduced to the history of Williamsburg and Cypress Hills through the artifacts and information cards, the students begin to learn more about the people who lived in those neighborhoods from articles published at the time in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and The New York Times. From these stories, they begin to understand how difficult life in the nineteenth century could be for children.

The class discovers that within blocks of the Ten Eyck Street site, children as young as 12 years old worked 12 hours a day, six days a week. One group of students is particularly moved by the story of several dozen young girls employed at a rope factory near the site who went on strike when their pay rate was reduced after the introduction of more efficient machinery. Considering their artifact—the head of a small ceramic doll—the students are struck by how the childhoods of these young girls were thwarted. Another group of students is able to connect a medicine bottle with news reports of people who had been sickened by patent medicines containing carbolic acid. They also notice advertisements for medicines designed to treat childhood ailments, such as colic, that openly proclaimed that they contained opiates such as codeine or morphine.

Once the students have researched life and conditions in the neighborhoods where their artifacts were found, they are asked to write a letter or diary entry from the perspective of someone who lived there. One student takes on the persona of a young immigrant. She writes that her grandmother gave her a perfume ball before she left home and that it comforted her on her long journey to America. A boy in one of the classes writes as if to a brother that he has left back home in Ireland. He tells him that, at first, he didn’t understand what a spittoon was when he saw one in a New York City boarding house, but has since learned that it’s far more sanitary to spit chewing tobacco juice into a spittoon than onto the floor. In another assignment, the students are asked to write from the point of view of their artifact, imagining how it made its way from its owner’s hands in the nineteenth century to theirs in the twenty-first century. The children are led to wonder: Did that mourning brooch have a photograph in it when it was dropped into the backyard privy? Was that ceramic doll broken before it was tossed away—or was it discarded for some other reason?

One student, in response to a parasol handle she’s been asked to write about, creates the story of a woman who went out walking one day, taking a parasol along to shield her from the hot sun, as was the custom. When she stopped to sit under a tree, she set the parasol on the ground, where it was run over by a cart, sending the handle rolling down the street. Someone later happened upon the broken handle and threw it into a cistern in the backyard on Ten Eyck Street, where it remained until being dug up in 2010. Another student, writing from the perspective of the black mourning brooch, tells the story of its resting underground for more than a century before hearing the terrifying sounds of a backhoe coming to dig it up and the satisfaction it felt at being once again grasped by human hands.

For this group of students from the Bronx, handling pieces of the past stands the typical look-but-don’t-touch museum paradigm on its head. What has been, probably, the most rewarding aspect of the program is seeing, again and again, the deep chord that is struck when students are allowed to examine and connect with the past in this way. They start off on a journey in which they initially encounter an artifact without benefit of supporting materials. They work their way through a process, driven primarily by the power of their own curiosity. And as they go, their own research begins to provide the reward of knowing not just how an item was used, but in some way, something about the lives of the people who owned it, and the time they lived in. And perhaps doing so helps shape their understanding of their own lives.

Says one young boy, Hubert, “It was awesome to look at, touch, and examine objects from so long ago,” adding with excitement, “I felt like I worked in a museum!”

And, Rita, one of his classmates from the group that studied the vulcanite brooch, says, “I’ve never done that before, and I love it! I told my mom I’m going to be an archaeologist someday.”