Nearly 1,500 years ago, a Byzantine merchant ship swung perilously close to the Sicilian coastline, its heavy stone cargo doing little to help keep it on course. The ship’s crewmen were probably still clinging to the hope that they could reach a safe harbor such as Syracuse, 25 miles to the north, when a wave lifted the vessel’s 100-foot hull and dashed it on a reef, sending as much as 150 tons of stone to the seafloor. The doomed ship was carrying a large assemblage of prefabricated church decorations—columns, capitals, bases, and even an ornate ambo, or pulpit. These stone pieces lay on the seafloor for 14 centuries until a fisherman spotted some in 1959 while hunting for cuttlefish.

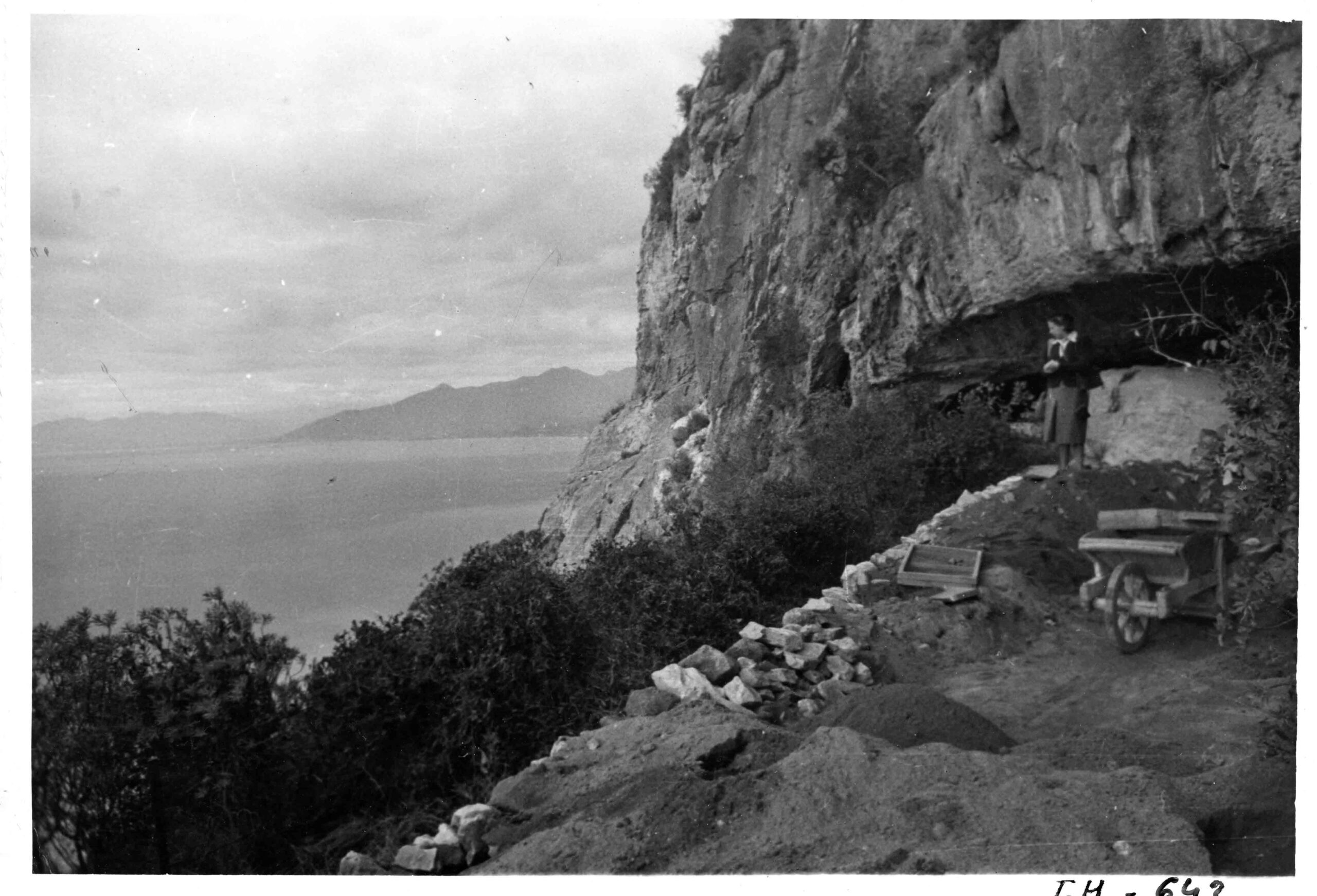

Covering an area a bit smaller than a football field and lying under 25 feet of water nearly a mile offshore of the fishing village of Marzamemi, the site was first studied in the 1960s by Gerhard Kapitän, a pioneering German underwater archaeologist. He believed the Marzamemi shipwreck played an important role in a massive state-led building campaign ordered by Justinian I, the great Byzantine emperor known as the “Last Roman,” whose name is synonymous with a resurgence in the fortunes of the Roman Empire in the Late Antique period. Based on several design details on the decorations, Kapitän concluded that not only had the ship sunk during Justinian’s reign, but that it had probably taken on its cargo—the decorative elements of a church’s nave—near Constantinople before heading west. He wrote that the marble blocks pointed to “the existence of a large organization clearly directed by a central administration” that dispatched the decorations for a new state-built church. Kapitän felt the Marzamemi marbles constituted “an almost complete set of elements for a Byzantine basilica with the certainty that all the parts are original and of the same period.”

Now, Stanford University archaeologist Justin Leidwanger and Sicily’s regional assessor for cultural heritage, Sebastiano Tusa, have returned to the Marzamemi shipwreck at the head of a team of archaeologists who are conducting a methodical underwater excavation amid the site’s boulders and reefs. Among the questions Leidwanger and Tusa want to answer are how the marble cargo got there and who was responsible for dispatching this consignment of expensive goods. “Somehow, the narrative of the shipwreck has been stuck since the 1960s in this notion that it’s Justinian’s church in a box,” Leidwanger says. “We have tended to assume that this is Justinian and his personal imperial circle shipping out churches to the corners of the Mediterranean.” But the team’s initial results point to a more complicated reality, a world where Justinian may have been emperor, but where commerce, including the shipment of large stone cargos, flourished because of the decisions of people whose names are lost to history.

Merchants had been shipping high-end decorative stone across the Mediterranean since at least the Bronze Age. While no shipwrecks carrying stone have been found dating to this period, it is evident that marble was shipped from ancient quarries on Aegean islands such as Paros and Naxos to sites that didn’t have their own sources. Shipwrecks carrying finished stone statuary dating to the later Archaic and Classical periods have been found off the coasts of Italy and Greece. But the shipment of stone for construction at an industrial level didn’t begin until the advent of the Roman Empire. “It really takes off then on a distinctly Roman scale,” says Benjamin Russell, a University of Edinburgh archaeologist who has studied Roman shipwrecks bearing stone cargoes. “You see a growth in administrative systems for shipping decorative stone throughout the empire.” Based on the number of shipwrecks found carrying stone bound for temples and other important buildings, the trade peaked in the third century A.D., when 24 ships bearing stone cargo are known to have sunk.

Then, in the fifth century, the Roman Empire was torn asunder. Its western provinces fell to the Germanic Vandals, Visigoths, and Ostrogoths, and long-distance trade networks collapsed. By the time Justinian I took power in 527, a Roman state encompassing the entire Mediterranean was a bygone reality. From Constantinople, Justinian began to pursue an imperial policy of restoring the empire by reconquering territories that had fallen to the Germanic kingdoms. His armies captured North Africa, Italy, part of Spain, and the main Mediterranean islands in the 530s. Justinian then set out to renovate and build fortifications and churches in an effort to reconsolidate the empire and promote his vision of Christianity.

Procopius, Justinian’s court chronicler, wrote a book cataloging Justinian’s extensive building projects, lavishing praise on the emperor for securing and beautifying restored Roman lands. Though Justinian is best known for building Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, he also ordered the construction of churches, fortifications, castles, baths, aqueducts, cisterns, and monasteries across the empire—from Jerusalem in the east to Spain in the west. Marzamemi lay at an important crossroads of the newly invigorated empire, where the two halves of the Mediterranean meet, an intersection of the trade routes crisscrossing the sea separating Europe and Africa.

Together with Brock University archaeologist Elizabeth S. Greene, Leidwanger has returned to the underwater landscape at Marzamemi each summer since 2014. The relatively shallow water allows long workdays so that two teams of underwater archaeologists can carry out dozens of dives each day to gently sweep away and suction up silt while searching for artifacts.

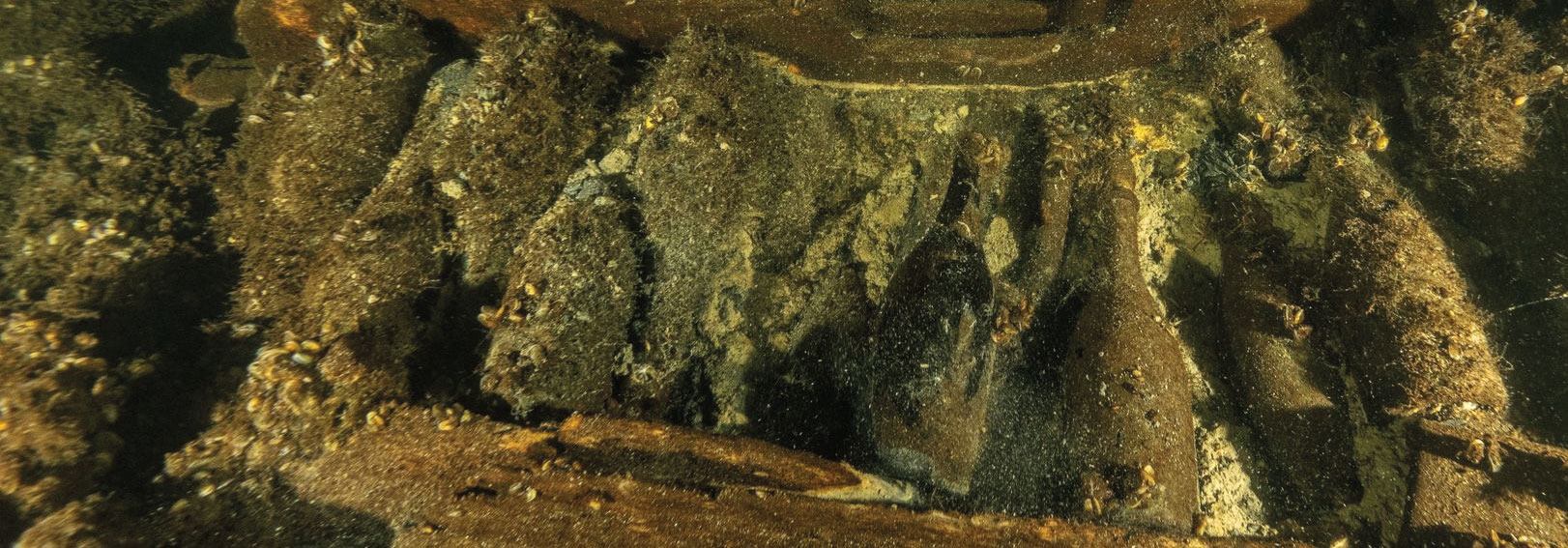

Unlike Kapitän’s, Leidwanger’s focus isn’t primarily on the monumental hunks of marble, which are now pitted by constant exposure to salt water. Instead, he and his team have the arduous task of scouring the seafloor for the small artifacts hiding in crevices and under rocks: ceramics, bits of pigment and raw glass, metal nails and fasteners, and fragments of the vessel itself. Their work is resulting in a much more comprehensive picture of what other goods went down with the ship.

Meanwhile, ashore, the Stanford team works with specialists led by architect Leopoldo Repola of Suor Orsola Benincasa University in Naples to create 3-D reconstructions of the architectural elements and conserve the artifacts hauled out of the sea in a winery-turned-museum. The 3-D reconstructions allow for close study of the marble remains and are giving the team a new look at the Marzamemi shipwreck’s ecclesiastical cargo. They have also recovered several more capitals besides the 28 capitals and 28 bases identified by Kapitän. And while they have also recovered hundreds of pieces of additional columns, they have located no further bases. These discoveries challenge Kapitän’s belief that the Marzamemi shipwreck was carrying a single, uniform set of church decorations. Leidwanger also notes that the ship’s fluted columns are “not as standardized as one would think.” The reconstructions show that the capitals may not all have been at the same stage of completion, and have revealed that some of their ornamentation is of an antiquated fashion for Justinian’s time. The team has found some bits of polished marble that Leidwanger likens to modern countertop samples, perhaps for showing to potential clients in antiquity. All this suggests that the merchant vessel that sank at Marzamemi could have been involved in trans-Mediterranean marble trade for a clientele outside the emperor’s circle.

A profusion of amphoras and other big storage vessels also helps create a picture of a ship that wasn’t just hauling imperial construction material on orders from Constantinople. Instead, it may have been an ordinary merchant ship traveling around the Mediterranean that took on a large shipment of marble. “In fact, much of what we find,” says Leidwanger, “whether it’s the sort of secondary cargo of wine, oil, and the like—tells us about a crew that’s routinely engaged in commerce.”

Procopius wrote that he documented Justinian’s profligate building “so that it may not come to pass in the future that those who see them refuse, by reason of their great number and magnitude, to believe that they are in truth the works of one man.” But Leidwanger and other modern scholars see room for local initiative in church building during Justinian’s revival. Not everything had to be micromanaged by Constantinople. “I think we really should be questioning the extent to which we need somebody like Justinian involved in this,” Leidwanger says of the Marzamemi church wreck.

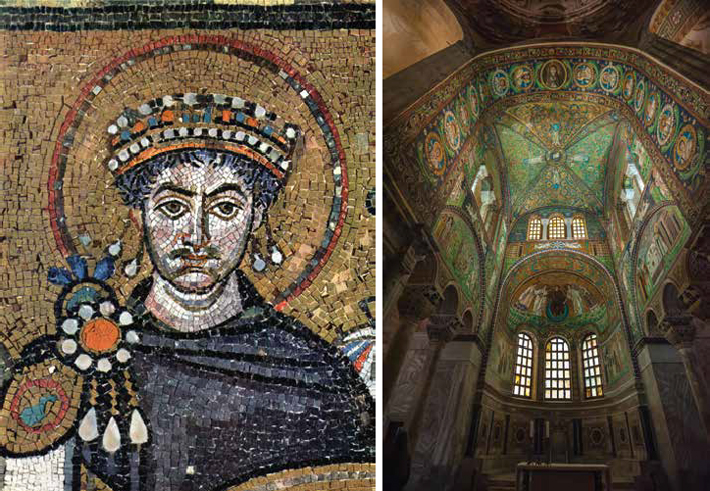

Although monumental edifices such as Ravenna’s Basilica of San Vitale, whose gilt mosaic preserves Justinian’s likeness, were probably built and designed by the imperial court, churches of lesser magnitude were likely financed and designed by provincial patrons, says Joseph Alchermes, an expert on early Byzantine art at Connecticut College. “For certain kinds of imperial projects, I really can’t imagine anything but a pretty centralized administration,” he says. But he notes that probably wasn’t always the case. While Constantinople was pushing its style of architecture as a means of asserting authority, local officials would have tried to assimilate by adopting the fashion of the time. Alchermes says, “It’s a two-way street.”

While some of the Marzamemi shipwreck marbles resemble the architecture in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Leidwanger has found that the marbles don’t comprise a complete church. Most religious buildings of the time would have been built of local material and only embellished with luxurious appointments. “These are the highlights, both visually and liturgically, in the church decoration,” says Alchermes. “These are the things that people really focus their attention on.”

Looking beyond the top-down imperial hypothesis may also help solve the question of where the Marzamemi marbles were bound. “Justinian is not sending some massive, beautiful, high-end church to some Podunk town. That’s not how it works,” says Leidwanger. Instead, the cargo could well have been ordered by local authorities furnishing their churches with prefabricated decorations. This begins to suggest a number of options for where the cargo could have been going. Some candidates for destinations include northern Italy, the Adriatic coast, or North Africa.

“The picture at Marzamemi is nowhere near as neat as was originally assumed,” says Russell. “What they’ve shown is that rather than one church, the cargo could have contained multiple elements intended for several buildings, and that changes the way we think about who was responsible for the cargo.” Russell points out that since the Marzamemi wreck was discovered, at least nine other shipwrecks bearing some stonework dating to the sixth century have been found in the Eastern Mediterranean, and that probably many more still wait to be found. “Marzamemi isn’t an outlier,” says Russell. “It fits into this context of resurgence in trade in the Late Antique period.”

Meanwhile, work at the site continues, and the study of the shipwreck’s more humble items promises to help flesh out the vessel’s story. Recently the team subjected iron concretions found on the shipwreck to X-rays and CT scanning. They found that while many are square nails used for the construction of the ship’s hull, others seem to represent a more diverse range of materials that may include tools such as chisels and hammer heads. These could have simply been basic shipboard tools for the repair and maintenance of the vessel or could have belonged to specialists in marble carving who accompanied the cargo in order to finish the stone decorations once they reached their final destinations. In the future, 3-D casts of the scans of these objects may help resolve such questions. Another promising area of research lies in further analysis of ordinary pottery found amid the boulders of the Marzamemi reef. Identification of the provenance of these ceramic wares could help reconstruct a logbook of the ship’s route. That itinerary would provide Leidwanger with valuable information about how the merchants of the Byzantine world took advantage of Justinian’s restoration of Roman power throughout the Mediterranean—a restoration that was short-lived.

The pan-Mediterranean empire Justinian forged gradually disintegrated after his death in 565, and the economic connections that bound that world together once again fractured. As a result, the stone trade fell off. Only two Byzantine wrecks dating to the seventh century bearing stone have been found, and none at all dating to the centuries following. In fact, the trade in major stone consignments represented by the Marzamemi shipwreck would not resume on the same scale in the Mediterranean for almost a thousand years after the vessel went down.