Brooklyn’s Dead Horse Bay looks about as appealing as it sounds, resembling something out of a postapocalyptic movie. On most days it is devoid of people, yet an improbable amount of debris blankets its shores. Glass bottles, old leather shoes, car tires, broken dishes, children’s toys—along with mysterious sun-bleached bones—are everywhere. As waves splash against the hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of glass fragments on the beach, and then retreat, a sound almost like wind chimes can be heard. This otherwise quiet and remote peninsula juts out into the mouth of New York’s Jamaica Bay. Given its prominent position at the bay’s entrance, one might assume that this barrage of material came to rest on this sandy spit through the idiosyncrasies of tide and current. But larger, heavier items such as metal safes, car parts, chunks of flooring, and bathroom fixtures suggest that it was not chance that bore these artifacts here.

The sea- and sun-stained appearance of objects, the rust, the faintly legible labels bearing the names of unfamiliar and long-defunct companies, and, of course, the bones, suggest that this material is not new. In fact, these objects were buried here decades ago but are now gradually reemerging along the beach. They are not just rubbish, nor flotsam or jetsam, but the remnants of little-known chapters in New York City’s history.

The shores along today’s Dead Horse Bay were once part of a place called Barren Island. Although Barren Island is nowhere to be found on most modern maps of New York, this peculiar little place played an integral role in the city’s history. “It’s archaeologically very rich, but also very tangled and complicated because of the many different uses that the geography has had,” says Robin Nagle, an anthropologist at New York University. This area today little resembles the tidal flats, salt meadows, and sandy beaches that Dutch settlers first encountered in the seventeenth century and curiously named Beeren Eylandt (“Island of Bears”). Originally, the island comprised about 30 acres of uplands and 70 acres of salt meadows, but land reclamation projects during the first half of the twentieth century permanently altered the topography. Well before that, however, its remote location made it the perfect spot for solving an intractable city problem.

It is fitting that today, in the twenty-first century, Dead Horse Bay is notorious for having New York City’s filthiest beach, since throughout its history, this particular corner of New York has been synonymous with refuse, offal, and unpleasantness. That reputation dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, when the city began shipping its garbage to Barren Island.

Located around a dozen miles southeast of downtown Manhattan, the area was relatively peaceful during New York’s early history. But its remoteness eventually caught the eye of city officials and entrepreneurs. By the mid-nineteenth century, New York faced a serious dilemma about what to do with its rubbish, particularly its deceased horses. In an era before cars, horses were everywhere and, of course, they died. One might not give it much thought today, but disposing of a horse carcass was not an easy task, and often they were simply left to rot in the streets. After a cholera epidemic broke out in the city, officials decided to seriously crack down on health hazards, which included finding a resolution to its dead horse problem. Because Barren Island was mostly uninhabited and was isolated from the rest of the city, it was deemed a logical location to build the much needed, and extremely odorous, animal disposal facilities.

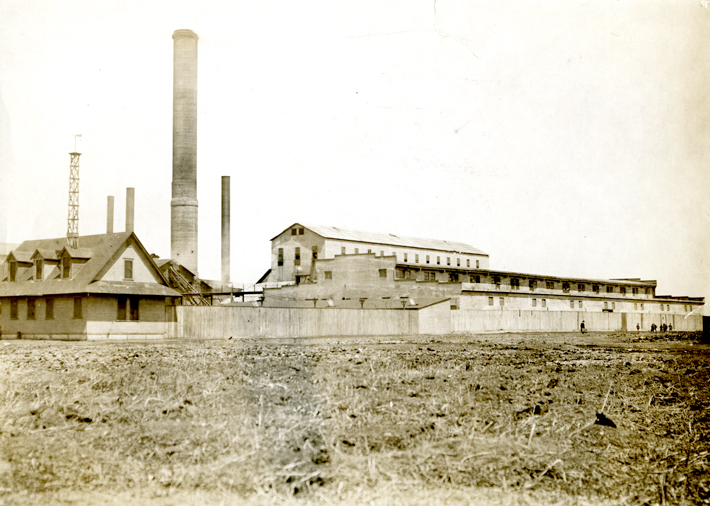

By 1859, the first two horse rendering plants appeared. They would not be the last. Between then and 1934 as many as 26 different waste management companies set up shop. Barges delivered the putrid and rotting carcasses to the island daily, where the remains were dismembered, chopped up, and boiled in large vats. The horse fat, blood, tissue, and marrow were used to manufacture a variety of profitable products, including fertilizer, glue, soap, grease, and even nitroglycerin. As many as 20,000 horses (in addition to dead cats, dogs, and other stray animals) were processed in a single year. The skeletal remains were tossed into this small inlet in Jamaica Bay, giving rise to its new moniker. Century-old horse bones remain plentiful and visible along its shores today.

Once the horse rendering industry was established on Barren Island, other similarly noxious trades joined them, such as fish and guano processing. By the end of the nineteenth century, New York City was not just sending its dead animals to Dead Horse Bay, but almost all its household garbage as well, to be incinerated, reduced, and processed in its facilities. At its height, it was receiving 3,000 tons of garbage a day, on top of all the dead horses from Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn, making it the largest waste reduction site in the world. For the factory workers and their families, life on Barren Island was nearly intolerable. The stench from burning flesh was detectable four miles away and capable of inducing sickness at two miles. Nonetheless, a small community developed there, just a few hundred yards from the furnaces. It consisted mostly of poor European immigrants and black Southerners—the only groups willing to work under such awful conditions. Residing and working on Barren Island came with a social stigma. “The people that lived there were doing work that was essential to the city’s public health, yet they themselves were ostracized and painted as sort of semi-savage and not even quite human,” says Nagle. At its height around the turn of the twentieth century, Barren Island’s population peaked at between 1,500 and 2,000, which does not include the swarms of wild dogs and pigs that plagued the island and scavenged the decomposing offal. In addition to the industrial complexes, the island contained a few streets, a school, a couple of churches, a post office, and several saloons.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, a number of factors led to the gradual diminishment of Dead Horse Bay’s waste industries. Not only had cars begun to replace horses, but the complaints from encroaching Brooklyn neighborhoods about the island’s noxious odors reached a fever pitch. The controversy even embroiled then-governor Theodore Roosevelt, who called Barren Island a “nuisance of the worst kind” and vowed to transfer its industries to other locations. The city finally stopped shipping its garbage there in 1918 and the animal processing factories gradually began to shutter. Today, the horse rendering facilities, the smokestacks, and the rows of workers’ houses are gone. Very little of Barren Island’s former infrastructure remains apparent, apart from a few decrepit wharves where the garbage scows and horse barges once docked.

As these industries closed and the workers moved out, the city devised a new plan for Dead Horse Bay. In the 1920s, landfill projects began expanding Barren Island’s shores, and it was eventually joined to the mainland. The principal motive behind this was the construction of Floyd Bennett Field, the city’s first municipal airport, but other projects continued to further alter the topography. The last remaining residents were forcibly evicted by controversial New York City Department of Parks commissioner Robert Moses in 1936 who planned to build a new park, new roads, and a major bridge connecting Barren Island to Jamaica Bay’s south shore. City residents from other parts of New York would soon have their histories intertwined with those of Barren Island and Dead Horse Bay.

From the 1930s until the 1950s the island’s terrestrial footprint continued to grow as the city dumped its garbage into the bay and covered it with soil, thereby manufacturing new usable land. Moses oversaw much of this land reclamation project. Perhaps no other individual transformed the topography of New York City and the surrounding region to as great a degree. For almost five decades, his innumerable urban development projects created new parks, bridges, recreational areas, and hundreds of miles of highway. Moses also loved to build land itself. He converted thousands of acres of New York’s waterways and wetlands into usable space by filling them with the city’s waste.

This process was not always as innocuous as it might sound, especially as it pertained to Barren Island, and Moses, who died in 1981, remains a polarizing figure. What the artifacts at Dead Horse Bay clearly show is that the fill used there was not just common refuse. It was made up, rather, of the forfeited possessions of countless New York City households whose owners were forced to leave them behind. “Every time I go to Dead Horse Bay, I am deeply moved,” says Nagle. In addition to her teaching duties, Nagle is also the anthropologist-in-residence at New York City’s Department of Sanitation. For close to two decades she has been sorting through, collecting, and analyzing the debris along Dead Horse Bay. In that time, she has noticed a difference in its “garbage” that distinguishes it from other landfills in the city. “I don’t think there was ever much trash here,” she says. “I think this is, by and large, rubble of houses, stuff of people’s lives, things that filled homes—the intimate, personal, mundane stuff of everyday life. That is now what is scattered on the beach.”

Many of Moses’ new city projects came at the detriment of working-class families. All over New York City, under the aegis of eminent domain, entire neighborhoods—usually poorer ones—were bulldozed to make way for Moses’ new highways. Because lower income families commonly could not afford moving trucks and, in addition, were given limited time to decamp, they were forced to leave many of their belongings behind. In the early 1950s, as entire city blocks were obliterated, the rubble of those houses was scooped up in toto and dumped into Dead Horse Bay. Ultimately, these deposits were covered with a thin layer of sand and soil in order to build part of Marine Park, Brooklyn’s largest public park. It was the city’s intention that what lay beneath its newest beach and recreation area would remain forever obscured.

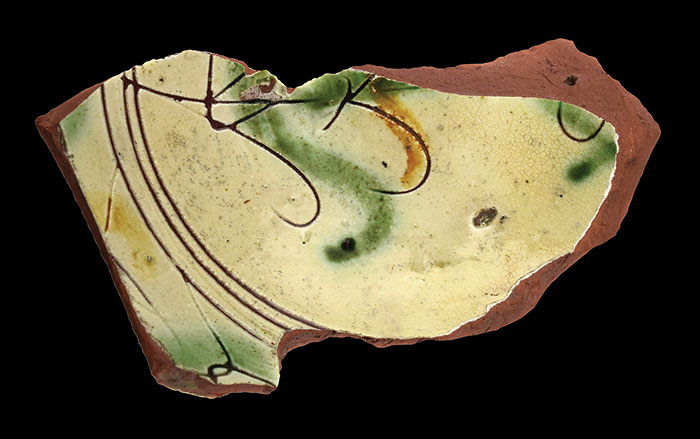

For reasons that are still not entirely understood, Moses’ men did a horrible job of capping the fill for this particular project. As a result, now, some 70 years later, the archaeological remnants of those condemned households are reemerging along the shore. The scene is both haunting and engrossing. For archaeologists like Alyssa Loorya, founder of Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, it is the deeply personal nature of some of the objects that is riveting. “On a trip there last year I saw some old vinyl records, perhaps part of someone’s record collection. As an archaeologist,” she says, “I am always fascinated by the items that represent someone’s personal interests.”

Nagle likes to point out that Dead Horse Bay would be a perfect place for a Hollywood prop master to visit, one tasked with re-creating the interior of a 1950s New York apartment. People’s homes and lives can be pieced back together through the veritable graveyard of objects here. There are food and drink containers, cleaning supplies, even small kitchen appliances. There are children’s belongings such as toy soldiers, dolls, and roller skates. There are work-related items such as leather boots, hammers, and saw blades, and hygiene products such as deodorant canisters, toothbrushes, and combs. There are even parts of the buildings themselves—architectural elements, bricks, tile flooring, and door lintels. “That top layer of debris is the story of people whose lives are rarely part of the formal account, who are not the power brokers, not the people with a lot of money and influence,” says Nagle. “If we pay attention to it and give some time and thought to Dead Horse Bay, we will recover some of the story of the city.”

And then there are the glass bottles, a seemingly infinite number. According to Nagle, one of the reasons there are so many of them is that a Prohibition era law made it illegal to refill or reuse any glass bottle. The law wasn’t repealed until 1964, so for decades New York City was flooded with single-use glass containers.

Although one of Robert Moses’ favorite methods for “rebuilding” New York was to create solid land where it previously didn’t exist, this was by no means an innovation. New Yorkers had been extending their coastline and creating real estate with landfill since the days of the earliest Dutch colonists. What is peculiar about the land reclamation in Dead Horse Bay is the process itself. After the rubble of wrecked houses and the belongings of displaced families were poured into the bay, they were never fully stabilized. When the last wave of dump trucks unloaded their cargo in February or March of 1953, Moses covered and sealed these layers with just a thin deposit of sand and topsoil, which inevitably has not endured over the past three-quarters of a century. “It’s puzzling,” says Nagle. “By that time landfill technology was already far more sophisticated than just dump and cover. Dead Horse Bay is basically a dump that feels like it got covered in a rush, and then city officials walked away. What on earth was the logic of doing such a sloppy job?”

Loorya thinks that the rural nature of the site and the fact that it was largely designated to be parkland and not intended to be heavily built upon may have influenced their shortcut approach. “In and around Jamaica Bay, you had a much more isolated area, and formal methods and customary landfilling devices were not employed to create the land. There was no deliberate or coordinated effort to create city streets that would be inhabited,” she says.

Whatever the reasons may be for Moses’ and the city’s incompetence, the reality is that objects buried decades ago are now reappearing. “Varying environmental and climate factors come into play with regard to Jamaica Bay,” says Loorya. “Climate change, storm erosion, and rising sea levels all contribute to the ongoing exposure of the landfill.”

Every storm, every anomalous high tide, eats further into Dead Horse Bay’s embankments and reveals new material. It appears endless. At low tide it is nearly impossible to take a single stride along the beach without stepping on a glass bottle or some early twentieth-century household item. This assemblage is currently at the center of an ongoing debate: Should it be considered archaeological and historical material or is it simply discarded refuse that is part of a public landfill? For decades, local artists and collectors have been combing the shores and illegally removing items of interest, arguing that they have free license to pick through and take whatever they want. Others want the bay to be considered a historical site and for the artifacts to remain in situ. For Nagle, the issue is complex. She can sympathize with both arguments, as both ultimately seek to preserve the legacy of Dead Horse Bay. “There is the loss from people taking things, but then there is also the loss due to time and tide and water given the volatility of Jamaica Bay. The glass is going to be somewhere under the water, but the smaller things, especially the lighter plastics, those will be lost forever, even if we don’t take them,” she says.

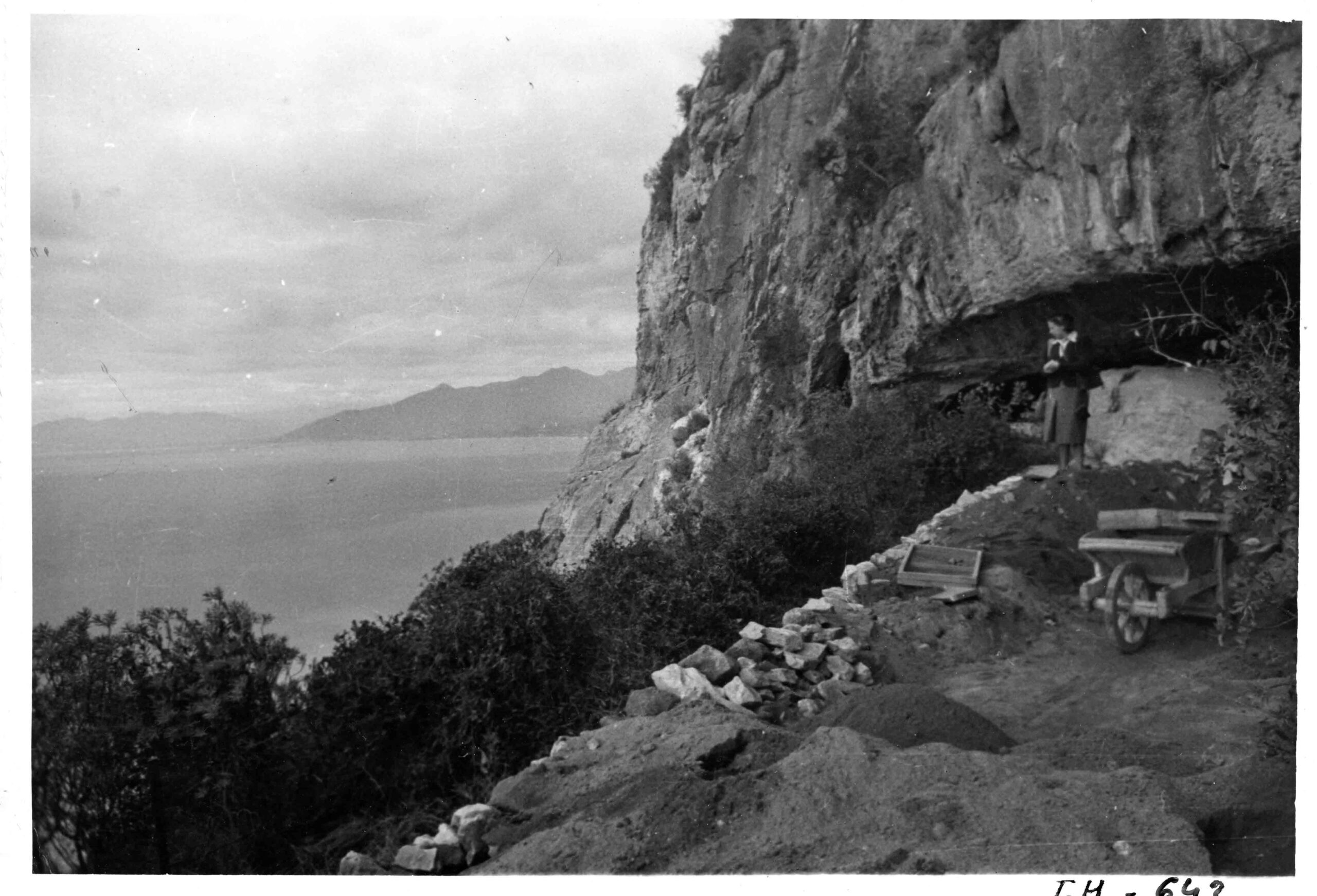

Part of the problem is that there has never been an extensive archaeological investigation. There have been small excavations nearby and informal surveys, but no organized evaluation has ever been attempted to either document what is there or to delve further into the history of Barren Island, Dead Horse Bay, and its landfill. “There has been no thorough archaeological analysis of any of it,” Nagle says. “If we are looking at the subfield of archaeology—that is the archaeology of the contemporary past, then this is a perfect case study. It connects to so many really urgent themes like urban development and displacement. I have yet to find a precise source of the top layer. Where did that rubble come from? Whose homes were those that were torn down and dumped into this place?”

The decision to implement any kind of formal archaeological project would have to be made by the federal government, as this section of Jamaica Bay is now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area, a 27,000-acre coastal national park. Whether or not an investigation is ever initiated, the objects on the beach along Dead Horse Bay will continue to be a tangible reminder of an intangible past—both of the families whose homes were destroyed and of the alienated community and the industries that once resided on Barren Island. There is still much to be learned either way. “We have a tendency as human beings to forget, and that’s understandable. Our lives are full and the demands are many,” says Nagle. “But in that forgetting we also lose a sense of who we are, and in the context of New York City, through Dead Horse Bay, we are able to not only learn more about the city itself, but also about our antecedents living just a few generations before us.”