Ancient canyons, dry mesas, and high deserts form the iconic landscape of what is now called the American Southwest. To the Navajo, who call themselves Diné (“the people”), this is sacred land, a place they know as Dinétah. It’s the center of their universe, the place where Diné history began. The story of their emergence is passed from generation to generation through days of oral accounts that describe how their ancestors traveled through four worlds—black, blue, yellow, and white—moving through each at an appropriate time, aided by sacred creatures, usually animals or insects, to arrive at the present world. “I think this is a metaphor for the stages of development of our human consciousness and human spirit,” says Navajo archaeologist Adesbah Foguth. Foguth works as an interpretive ranger at Chaco Culture National Historical Park just to the east of the Navajo reservation in the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah. When she gives tours of the park, she shares Native histories and talks about the Navajo connection to this land. “We evolved here, we became distinctly Navajo people here,” she says. Her understanding of Navajo emergence also includes a sense of movement and change. “We were also literally migrating on the landscape, moving from place to place.”

Navajo is part of the largest indigenous language family in North America, known as Dene, which includes more than 50 languages spoken by Native peoples in the Canadian Subarctic, the Pacific Northwest, and the American Southwest, where the Navajo and their distant cousins, the Apache, are among its southernmost speakers. Currently, archaeologists are attempting to trace the epic 1,500-mile-plus journey the ancestors of the Navajo and Apache made across North America’s mountains and plains. This was one of the most consequential population movements in North American history, taking people from the Canadian Subarctic, among the wettest landscapes in North America, to the desert Southwest, its most arid region. At the beginning of the migration, the ancestors of today’s Navajo and Apache were foragers. Centuries later, many of their descendants had become farmers. This massive migration forever changed the cultural landscape of the Southwest.

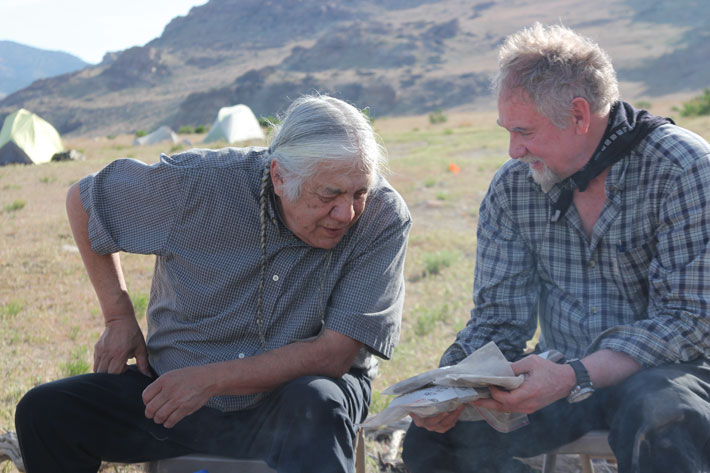

One effort to comprehend this great migration is the Apachean Origins Project, headed by University of Alberta archaeologist Jack Ives and Brigham Young University archaeologist Joel Janetski. “Apachean” refers to a subgroup of Dene speakers comprising the Apache and Navajo. Ives and Janetski lead a team of researchers using archaeological, linguistic, isotopic, and paleoenvironmental evidence to study the links among distant Dene speakers. They also work closely with Dene elders to understand not just when the migration happened, but how the migrators interacted with people they encountered. “Migration creates an infinite number of scenarios for contact with new people,” Ives says. Those interactions can lead to intermarriage, shared cultural traits, and a coalescence of what previously were two or more distinct peoples.

Ives and Janetski have focused their work on a remarkable site, which, nearly a century ago, provided surprising evidence that a culture accustomed to life more than 1,000 miles north in the Subarctic also lived in the American West. How they got there and what happened along the way are a sometimes misunderstood, uniquely North American migration story.

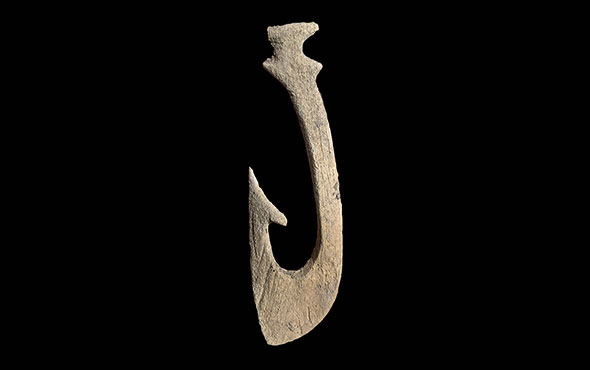

In 1930, a young University of Utah archaeologist named Julian Steward began excavating in two caves on Promontory Point, a peninsula on the northern edge of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. The caves’ dry environment proved ideal for preserving artifacts, and over two years, Steward found baskets, pottery, fiber ropes and mats, juniper bark, bison bones, arrow points and shafts, bow fragments, knife handles, scrapers, and awls. He also found the remnants of some 250 moccasins that strongly resembled footwear made and worn by Canadian Dene cultures past and present. Each of the carefully stitched intact moccasins, which are now stored at the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU), reflects the size and gait of the person who wore it. Some are tiny, made for children. Some have blown-out heels that were later repaired. A few have decorative porcupine quills, and all have small stitches and puckering around the toes. And, 700 years after the Promontory people wore them, these moccasins still smell strongly of smoke—a reminder of the fires used to tan their hides. The moccasins Steward found are unlike those made by the neighboring people who belonged to a farming culture known today as the Fremont. Although the Fremont created elaborate rock art and clay figurines, their moccasins don’t have the distinctive puckered stitching and quillwork of those found in the caves.

The presence of the Dene-style moccasins in Promontory Caves led Steward to suggest a groundbreaking idea for the time: that the site’s early occupants were bison hunters of Apachean ancestral origin who had come to the Great Salt Lake from the Subarctic and Northern Plains. If he were right, Promontory Caves would likely prove to be a pivotal location for the study of North American migrations and the cultural evolution of indigenous tribes. But Steward never returned to the site to gather further evidence to test his hypothesis and his research stalled. Twentieth-century scholars continued to debate the ancestral origins of the Navajo and Apache, but never came to a consensus. Some suggested that Apacheans arrived in the seventeenth century during the Spanish colonial period.

About 20 years ago, Ives and Janetski realized they shared an interest in Promontory Caves and the distinctive moccasins Steward had unearthed there. “Jack and I decided, gosh, it would be nice to go back to those caves,” Janetski says. The two assembled an interdisciplinary team with the goal of precisely dating the artifacts and testing Steward’s theory that the caves had sheltered Apache and Navajo ancestors during their southward migration. And they wanted to better understand the people who had left their shoes on the caves’ floors.

One of their first efforts was to radiocarbon date Steward’s moccasins. They found that the dates centered around A.D. 1250 to 1290. This exceptionally narrow time frame suggests that perhaps just a few generations of Apachean ancestors lived in the cave some 400 years before the Spanish colonial period to which some archaeologists had linked early Apacheans. The thirteenth century was a time of extreme drought in North America. The archaeological record shows that the Fremont in the area around Promontory Caves abandoned farming during this time, and, out of desperation, turned to foraging. But the people living in the caves seem to have thrived as bison hunters. “This was a healthy, vibrant population that was doing really well,” says Ives. When Ives and his team conducted their own excavations at Promontory Caves between 2011 and 2014, they uncovered still more moccasins. By studying the sizes of all the moccasins excavated, they concluded that some 80 percent of them belonged to children or teenagers, suggesting that the mid-thirteenth century population of Promontory Caves was young and rapidly increasing.

Working with Native elders, the team was able to confirm that the style of the moccasins both Steward and they had unearthed was distinctly Dene. One of these elders is Bruce Starlight of the Tsuut’ina Nation, a Dene people who live on the plains of modern-day Alberta. “I never talk about something I don’t know,” says Starlight. He has examined the Promontory Caves moccasins and believes they prove Dene people once lived at the site. “The Dene still have that style of moccasin,” he says. The footwear could even have been used as a form of identification. “A long time ago, when they did battle among each other, the first thing they looked at was your moccasins,” says Starlight. Unlike the simpler Fremont moccasins, those found in Promontory Caves would have required a lot of time and a high degree of skill to make. Ives speculates that the moccasins might not only have been an expression of culture, but of care for the makers’ loved ones. “The moccasins are highly evocative,” says Ives. “We all react to them on a human level; you can sense a person.” Many of them still have distinct indentations of toes, the individual marks of the people who wore them as they walked across the landscape.

In addition to the moccasins, the team unearthed more bison bones, hide scrapers, sewing awls, small beads, and fragments of woven mats and baskets. Perhaps the most significant group of artifacts they excavated is a large collection of gaming pieces. This evidence of gambling is particularly telling, says Canadian Museum of History archaeologist Gabriel Yanicki. “These games weren’t just recreational pastimes,” he says. They were a proxy for communication, indicating that contact between groups was taking place. Native elders have explained that when two groups speaking different languages and from different cultures encountered each other, they had a choice: “They could fight,” Yanicki says, “or they could gamble.”

The gambling items from Promontory Caves include a juniper-bark ball, decorated sticks, badminton-style birdies, hoops, and darts. But the most common artifacts are dice made of cane, which, Yanicki says, were typically used by women. While Native dice games varied across the continent, they usually involved tossing two-sided objects in a basket or bowl or striking them against a hard surface. Gamblers could earn points depending on whether the dice landed face up or face down. Gaming would have led to other social interactions, from meetings and feasts to alliances and intermarriages. “That’s how new societies ultimately form, as groups spend more time together and forge mutual futures,” Yanicki says, adding that this results in the emergence of new social identities.

Recent genetic studies support the idea that marriage between different groups was common during the Apachean ancestral migration. Mitochondrial DNA samples show that modern-day Navajo and Apache have genetic markers from a variety of haplogroups, or genetic groups that share common ancestors. “As Apachean ancestors left the north and progressed farther south, a lot of people entered their society,” explains Ives. Over time, people with primarily northern maternal lineages were joined by people with southern maternal lineages. “It’s right there in the genetic record,” he says. The Promontory Caves people may have recruited women from other societies—as bison hunters, there would have been an abundant need for workers. “Bison meat is somewhat unusual in that it is prone to quick spoilage, so it’s imperative that you immediately get the hide off the animal and allow the carcass to cool,” Ives says. “And it’s women that carry that load.”

None of this surprises Bruce Starlight. “We were great migrators,” he says. “It’s deeply embedded in our stories.” Archaeologists now know that around A.D. 840, a massive volcanic eruption of Mount Churchill in Alaska ejected so-called White River Ash that spread across Canada and as far as Europe. Researchers believe it’s possible the eruption’s impact on the environment and the extreme cold that resulted could have spurred many Dene people to migrate south. Dene oral traditions ranging from Canada to the Southwest include stories that link volcanic eruptions and periods of extreme cold.

If the eruption of Mount Churchill severely disrupted the lives of Dene ancestors, that could help explain why members of the Dene language family are spread across more than 1.5 million square miles. “That’s a huge language family,” says University of Alberta linguist Sally Rice, who works with Ives. She has spent decades compiling a list of 25,000 Dene words including terms for objects, flora and fauna, and things that would have been novelties to populations moving south. For example, northern Dene people have no word for cactus, and Dene speakers in the Southwest refer to cacti using a term that essentially translates as “rose thorn.” Unlike cacti, roses are widely found in the north. “Language itself is a kind of archaeological record,” says Rice. Another example is the overlap in words for “spoon,” “horn,” and “gourd.” In northern Dene cultures, people used horns as spoons or scoops; in the south, people used gourds. The words used to describe these items are all related. At Promontory Caves, Steward unearthed examples of bison-horn spoons.

The Promontory Caves moccasins also display evidence of a southward journey. While Dene footwear was originally designed for cold weather, with fur lining and leather ankle wraps, some of the Promontory Caves moccasins do not include the ankle wrap. “The leggings come off and it becomes a summer moccasin,” says Glenna Nielsen-Grimm of the NHMU. “It’s an adaptation.”

Starlight is one of just a few dozen people who still speak his native Tsuut’ina language, and he is involved in multiple projects to revive the language and bring together Dene peoples from across the diaspora—from Canada, Alaska, and the Pacific Northwest, and south into Mexico. At one of these gatherings, Starlight says, he told a Tsuut’ina story about a dog that stole food from a man’s tepee. Both the dog and the man die in the story. Hearing this, an Apache man from New Mexico stood with tears in his eyes and told Starlight, “I was just a little boy and my grandma used to tell me this story.”

At these meetings, which also include Ives and his team, Dene people have forged connections across the continent. “When I went to that conference, I discovered I had half of Canada related to me!” says Veronica Tiller, a Jicarilla Apache author and historian from New Mexico. “They know things that we don’t know, and we know things that they don’t know. And to think that we’ve been apart for such a long time.”

Tiller is gratified to hear that the Apachean Origins Project has made great efforts to include and accurately portray Native perspectives, something that scholars haven’t always done. She cites the work of early anthropologists who visited her reservation, interviewed elders, and published the first written accounts of Jicarilla history. But the researchers missed the meaning of many of the stories, she says, because they weren’t fluent in the language, didn’t grasp the cultural context, and relied on Native translators who likely had a grade-school-level command of English. “That becomes the body of literature that’s supposed to illustrate who we are as a people,” says Tiller. She and her relatives are now retranslating the texts, which they hope to publish soon.

Like the Navajo, the Apache, too, chronicle their origins in emergence stories based in the Southwest. “It’s like you came out of the womb of the earth,” Tiller says, describing a movement from darkness to light that she likens to a passage from a dark age into a more enlightened era. She thinks of the histories she grew up with, and how they might help shape questions for archaeologists today. “I remember my mother used to tell me that our people used to make an annual migration to Utah to get salt, probably from the Great Salt Lake. And I suspect that we’re not the only population that did that,” she says. Perhaps the lake served as a trading ground for multiple populations, she speculates. Salt is known to have been a prominent trade item among Plains and Apache groups, and objects found in Promontory Caves, such as an abalone shell adornment from the Pacific Coast, indicate that the people living there were involved in thirteenth-century trade networks that extended far and wide.

There is, in fact, growing archaeological evidence for ancestral Apachean groups moving into the greater Southwest as early as the 1300s. Archaeologist Deni Seymour has investigated several sites in southern Arizona and New Mexico that were used to store food, pottery, baskets, and other goods for later use among mobile groups. They were Dene-speaking peoples related to Apache and Navajo groups today. “Promontory Caves was just one of the stopping points along the way,” says Seymour.

When exactly, in the sense of a Western calendar, Apache and Navajo cultural identities emerged, though, remains an open question. “I realize this is a complex and sensitive topic for any community,” says Ives. That’s a compelling reason for archaeologists to consider both the scientific record and indigenous knowledge. For Foguth, who says she went to school for archaeology specifically because she felt that Native peoples were excluded from their own past, this is critical. “The best that professionals in archaeology can do today is to listen,” she says. “Listen and put aside your biases and what you ‘know’ to be true, and remind yourself that what you’ve learned is one story—and that there are other stories that are also true.” When she guides tourists through Chaco Canyon, Foguth ends her historical overview in the present. She talks about living people, where they are today, what they’re doing today, and their current struggles. She tells them that Navajo medicine people say they have entered the sixth world now, evolving into higher levels of humanity. “We didn’t stop migrating,” Foguth says. “We’re still migrating today.”