During the day, the rocky island of Samothrace in the northern Aegean Sea is often veiled by clouds. Wind sweeps across the landscape, and the turbulent waters remain, as they were in antiquity, dangerous for seafarers. When the clouds clear at night, however, the peak of Mount Fengari at the island’s center, which reaches a mile into the sky, becomes visible. From the vantage point of the peak, Homer relates in the Iliad, the sea god Poseidon watched the Trojan War as it unfolded. Nestled in a deep ravine in the mountain’s shadow lie the remains of the Sanctuary of the Theoi Megaloi, or Great Gods. From at least the seventh century B.C., pilgrims walked under the cover of darkness from the nearby ancient city, now known as Palaeopolis, to the sanctuary to be inducted into a secret religious cult. As they passed through an immense marble gateway onto the sanctuary’s eastern hill, they might have heard the rush of water coursing through a channel beneath the entranceway. Amid the sounds of music and chanting emanating from farther within the sanctuary, the prospective initiates reached a sunken circular court. Here, ritual dancing and other performances might have taken place, surrounded by bronze statues that were likely dedicated by previous initiates. The noise and darkness, as well as the use of blindfolds, probably induced an altered state of mind that prepared participants for the forthcoming rituals and sacred revelations. By the flickering light of oil lamps and torches, they began the steep descent down the Sacred Way, to the sanctuary’s heart, to be initiated into the mysteries of the Great Gods.

Because initiates were bound to keep the details of the rites secret, ancient literary sources provide scant details about the cult. Those writers who do discuss the mysteries often give diverging accounts and differing identifications of the gods. Coins dating to the second-century B.C. unearthed at the sanctuary depict a great mother goddess. Some ancient writers associate this goddess with a group of gods called the Kabeiroi. “What we know most clearly about the initiation are its promises and benefits,” says archaeologist Bonna Wescoat of Emory University. “Ancient sources strongly state that the Great Gods are powerful and protective gods. Most say they offer protection at sea, while some say they offer protection in times of need. The benefits they confer could have meant different things to different people, depending on what an initiate most sought from the experience.” Some writers even claim that initiates experienced a moral transformation. According to the first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, initiates into the Samothracian mysteries became “more pious and more just and better in all ways than they had been before.”

Despite Samothrace’s remote location, the mystery cult of the Great Gods was well known in the ancient world, second in popularity to the mysteries celebrated at Eleusis, outside Athens. Pilgrims traveled by ship from across Greece, the Black Sea region, Asia Minor, and Rome for initiation, which was offered whenever a sufficient number of participants arrived on the island during the sailing season, from April through October.

Samothrace and the Sanctuary of the Great Gods reentered the popular and scholarly imagination during the Renaissance. In 1444, the antiquarian Cyriacus of Ancona visited the island and sketched some of the sanctuary’s reliefs and sculptures. In 1863, the French antiquarian Charles Champoiseau uncovered the famed marble statue of Nike, or Winged Victory, which in antiquity stood above the sanctuary’s theater on its western hill. In the following decades, French, German, Austrian, Czech, and Greek excavators explored the hillside. American-led excavations, which began in 1938 and continue to this day, have unearthed monuments on the sanctuary’s eastern hill, sacred buildings in its central valley, and entertainment and dining facilities on its western hill. Yet, even after more than 150 years of nearly continuous investigations, fundamental details about the sanctuary—including the rituals and administration of the cult, and even the functions of the sacred buildings—remain elusive.

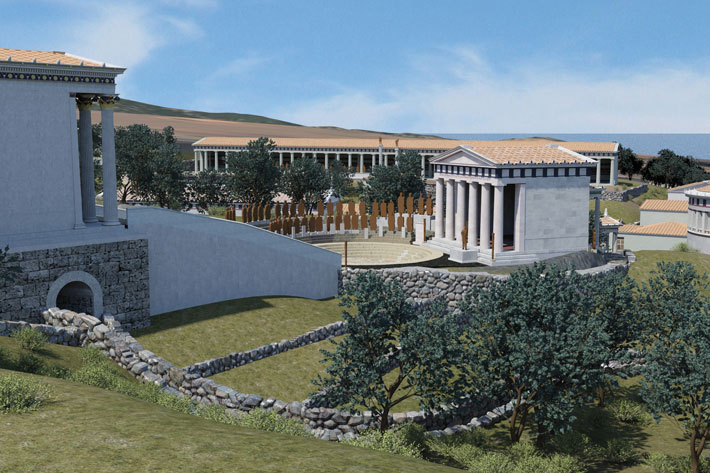

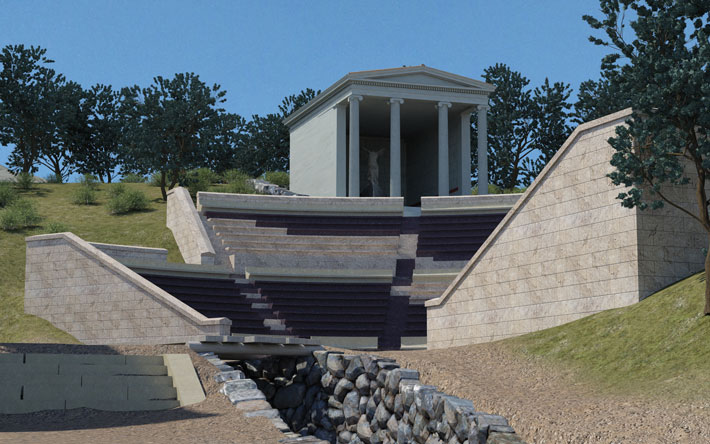

Over the past decade, an interdisciplinary team led by Wescoat, who has directed the American excavations since 2012 with the cooperation of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Evros, has turned its attention back to the western hill. By considering the interaction between the natural landscape and built environment, examining small votive objects and other items initiates left behind, and through survey, excavation, archival research, and 3-D modeling, the archaeologists have begun to re-create the sensory, spiritual, and emotional experience of initiates as they were introduced to the rites of the Great Gods. “We want to explore the landscape, the connectedness of monuments, ancient initiates’ route through the sacred spaces, and the issues of what they could and could not see,” Wescoat says. “These aren’t questions that have been asked in the past.”

Before the Greeks settled on Samothrace in the sixth century B.C., the Thracians, a group of tribes from the Balkans, settled its highlands between about 1100 and 900 B.C. After the Greeks’ arrival, the two groups seem to have coexisted peacefully. Fragments of sixth- through fourth-century B.C. pottery recovered from the island and from Zone, a Samothracian coastal outpost on the mainland, were inscribed in the ancient Thracian language using the Greek alphabet. “From these fragments and other considerations, it’s clear the Thracians kept using their language well into the Hellenistic period,” says epigrapher Kevin Clinton of Cornell University. Diodorus mentions that, at the time he was writing in the first century B.C., the Samothracians still used a non-Greek ancient language, likely Thracian, during the initiation rites. Elements of the cult of the Great Gods may hearken back to a native Thracian cult, Clinton says, though it is unknown what this cult’s contribution was to the rites celebrated in later periods.

The earliest material traces of religious activity within the sanctuary are seventh-century B.C. tankards for ritual drinking and remains of structures dating to the late fifth or early fourth century B.C. Reused blocks preserved in the foundations of these buildings and traces of monumental walls are vestiges of even earlier sacred structures.

By the mid-fourth century B.C., a few modest buildings had sprung up on the sanctuary’s eastern hill and in its central valley. Around this time, the Macedonian king Philip II (r. 359–336 B.C.) and his future wife Olympias, the parents of Alexander the Great, met on the island to negotiate their marriage and to be initiated into the cult. Their presence on Samothrace seems to have spurred elite patrons to invest in the sanctuary on an unprecedented level, beginning with the construction of a monumental marble building in the middle of the central valley around 340 B.C. This structure is now called the Hall of Choral Dancers after a frieze depicting more than 900 dancing young women that once wrapped around its exterior. The hall is the sanctuary’s oldest standing cult building and incorporated remnants of an earlier chamber into its core. Wescoat believes it may have been commissioned by Philip himself. “There was no gradual lead-up to this, just small buildings made of local materials and then—boom—this extraordinary structure built of imported marble,” she says. “It’s hard for me to see it as a project the Samothracians could have pulled off on their own.”

Over the next century, the Sanctuary of the Great Gods became an increasingly popular destination filled with grand monuments. These were funded by Macedonian royals including the Ptolemies, a dynasty that ruled Egypt from 304 to 30 B.C. Alexander’s successors, his half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and son Alexander IV, dedicated a marble building fronted by Doric columns during their short joint reign (322–317 B.C.). Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 284–246 B.C.) built the gateway that served as the sanctuary’s entrance. Opposite the Hall of Choral Dancers, Ptolemy’s wife Arsinoe II commissioned a rotunda that was the largest circular building in the Hellenistic world. “All these monuments transformed the sanctuary into an international center and a glittering display of power and opulence,” Wescoat says.

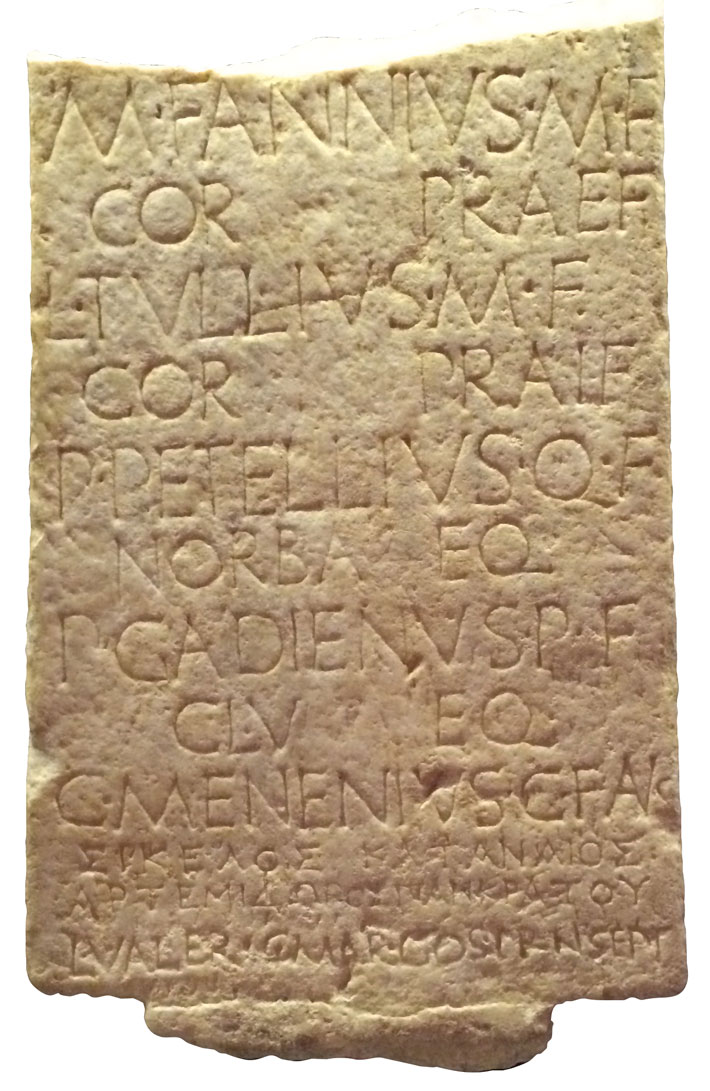

Although these royal dedications highlighted Samothrace’s most famous initiates and patrons, the sanctuary attracted a diverse set of sailors, merchants, and other pilgrims, some of whom may have participated in the mysteries, while others came for the island’s annual festival. Inscribed lists of initiates from the second century B.C. through the second century A.D., which have been found inside the sanctuary and in the adjacent city, record the names and places of origin of initiates who braved the treacherous trip to Samothrace. Whereas other Greek sanctuaries restricted participation in their rituals, Wescoat explains, the Samothracian cult was remarkably inclusive. “If you could make it to the island and bore no bloodguilt—whether enslaved, free, Greek, non-Greek, male, or female—you had the right to be initiated,” she says. Among those on the lists are theoroi, or sacred ambassadors from other Greek city-states, as well as Roman consuls and other officials, for whom initiation into the cult appears to have become part of a formal tour of the territories after Samothrace came under Roman control in 168 B.C.

When they reached the bottom of the Sacred Way, initiates had to squeeze through a tight passage between buildings to enter the sanctuary’s ritual zone. The descent into the valley created a kind of privacy reinforced by the placement and style of the buildings. “You can clearly see a performative aspect of staging drama through architecture,” says archaeologist Samuel Holzman of Princeton University. While temples and other religious buildings at most Greek sanctuaries were aligned along a linear axis, he says, architects on Samothrace combined the ravine’s natural topography and the arrangement of buildings to engineer a deliberately circuitous layout. “They created a winding interaction with these buildings, where you come upon them suddenly through twists and turns as you navigate the maze of architecture in the sanctuary,” says Holzman. Moreover, the cult structures were built in such a way that visitors could not easily see inside. “Almost all the sacred buildings have very deep front porches and big interiors where people could gather,” Wescoat says. “That goes along with cultic rites that are secret in nature, and not intended to be widely viewed.”

EXPAND

Winged Victory's Vantage

Since it was first displayed in 1883, two decades after its discovery, the nine-foot-tall marble statue of Winged Victory has awed visitors to the Louvre. In the sculpture’s original location above the theater in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace, the winged goddess Nike would have been equally captivating. “The statue was most brilliantly sited,” says archaeologist Bonna Wescoat of Emory University. “Standing where she once stood, you have this extraordinary sight line right down through the heart of the sanctuary.” For archaeologists, though, details about the monument’s dedication and ancient context are obscure. Renewed studies in recent years conducted by an international team of scholars are offering new leads.

Nike is depicted alighting on a warship’s prow that served as the sculpture’s base. A preliminary reconstruction from fragments of a stone ram, a battering device designed to pierce an enemy’s ship, that once protruded from the prow’s front has prompted the team to reconsider who was responsible for the monument’s dedication. The prow is made of blocks of Lartian marble, a blue-gray stone with pink and white veins that was quarried on the coast of the island of Rhodes. In addition to the Nike monument, Greek sculptors used Lartian marble for monumental prow bases erected on Rhodes and the nearby island of Nisyros. One of these bases is strikingly similar in scale and construction to the Nike statue’s base. Based on this, the researchers believe the Rhodians were involved with the monument, which surely commemorated a sea victory sometime in the second quarter of the second century B.C. “Rhodes was a huge sea power, and we know that the Rhodians were active in the sanctuary,” Wescoat says. “It would make sense for them to use this kind of prow as a base.”

Along with Louvre curator Ludovic Laugier, Wescoat and her team are also studying plaster fragments of large lion heads, the first of which archaeologists unearthed in 1939 within the area surrounding the Nike statue. Because they found water pipes on the hill, those early excavators speculated that the lions were waterspouts for a fountain on which the Nike statue rested. However, the pipes seem to have led to a colonnaded stoa and not to the Nike monument. A large cache of fragments of the lions’ manes were found in storage at the Louvre and still more were discovered during excavations of the theater in 2018. “With close to two dozen locks that seem to belong to at least three heads, we have to come up with a different explanation,” says Wescoat. She and her colleagues are now exploring the possibility that the lion heads might have adorned the roofline of a covered structure in which the Nike sculpture stood. This would have echoed other buildings in the sanctuary whose facades were also decorated with lion heads. However, the researchers cannot rule out that the building was unroofed. This would have allowed visitors to see the Nike sculpture more clearly against the mountains and sky.

The nocturnal timing of the initiation rites certainly would have heightened the drama of the natural setting. Moonlight and artificial light from torches would have only partially illuminated sculptures on facades and ornate coffered ceilings. “Throughout the sanctuary’s history, designers, architects, and patrons built monuments in a way that harnessed natural features of the landscape to increase the impressiveness and the affective, emotional power of the site,” says archaeologist Maggie Popkin of Case Western Reserve University. Disorientation caused by the sanctuary’s labyrinthine design might have evoked a range of emotions that are echoed in the few ancient accounts of the secret rites. Several sources mention the myth of the abduction of Harmonia, daughter of Zeus and Electra, by the hero Kadmos. According to the myth, Kadmos was one of the first people from outside Samothrace to be initiated, and while on the island, he whisked Harmonia from her home to the city of Thebes. Some versions of the myth also include a joyous wedding between Kadmos and Harmonia. “There was this emotional push and pull of loss and recovery, of terror and celebration,” Wescoat says.

The sanctuary’s design placed visitors in front of important buildings, but only allowed them to see the structures’ facades from particular angles. “The buildings would be revealed to viewers in a very specific way that gave them the full intended effect of the architecture,” Popkin says. For example, at the bottom of the Sacred Way, initiates would have approached the Hall of Choral Dancers from the side, not from its imposing front. They would have had to round the corner of the hall to see the sculptures that adorned its facade. Some ritual activity occurred inside the building as well, though it’s not clear to what extent initiates were involved. Inside the building’s two large chambers, archaeologists have uncovered bothroi, or ritual channels for pouring libations into the earth, and traces of small hearths. “This was probably the most important cult building,” Wescoat says. “Whether all initiation happened in it, and how it was designed to accommodate that, is a matter of great debate among scholars, including many of our team members.”

In order to more closely examine the physical and visual connections among the sanctuary’s buildings and how these connections impacted initiates’ and other visitors’ experience, the team created a 3-D digital model of the sanctuary that allows them to virtually walk through it from the perspective of an ancient visitor. “What we hadn’t put together as powerfully before was the way in which the space was like a diaphragm,” says Wescoat. “It opened up and then closed, creating a series of stations where initiates would have had to stop and gather.” Access to certain buildings would have also been restricted. Inscriptions in Greek and Latin discovered around the remains of two cult buildings proclaim that “the uninitiated are not to enter.” These inscriptions were not found in situ, and it’s unclear whether they referred to specific buildings or areas, or to the sanctuary as a whole. Given that restricting access to the entire sanctuary would have been difficult, especially since it was not surrounded by walls, Clinton believes the inscriptions likely referred to specific areas. “The boatloads of visitors would undoubtedly include people that were not going to be initiated,” he says. “There would have been areas that could accommodate them.”

Beyond the open space in front of the facade of the Hall of Choral Dancers, the prescribed route becomes unclear. It seems that visitors could go in a few different directions. Digital modelers are exploring potential pathways through the sanctuary using gaming software and agent-based modeling, which simulates the movements of groups of people who are given a degree of autonomy to make collective decisions. Even with the potential for more freedom of movement, the central valley’s topography nevertheless structured initiates’ pathways. Today, as millennia ago, a natural torrent runs south to north through the length of the sanctuary and out to sea. Past excavators largely viewed this water channel as a nuisance, but in recent years the team has reconsidered it as a kind of monument in itself that may have played an integral role in initiation. In 2019, they excavated along the torrent and documented the ancient course of its channel, which was at least 13 feet deep and 13 feet wide at its broadest point. It is unlikely that the channel was covered, says archaeologist Andrew Farinholt Ward of Indiana University, and though little evidence of bridges survives, there were crossings at a few key points. Initiates would have had to cross over the torrent at least twice to access the southern area of the sanctuary and the theater. “They would have looked down into the channel that, at certain times of year, was rushing with water,” Ward says. “They might have been terrified, the power of the water eliciting a ritual fear that the Greeks liked to have in their sanctuaries. I think part of the reason why they left the ravines open and visible is that even when the torrent wasn’t rushing through, visitors would have still been reminded of that potential.”

As they crossed over the torrent to the western hill, perhaps as the first light of morning began to stream into the valley, initiates had a clear view of the Nike statue. By this time, the researchers believe, they would finally have been inducted into the cult’s mysteries. The structures on this side of the sanctuary served as a kind of entertainment zone where pilgrims could celebrate their initiation. At the base of the hill, archaeologists have uncovered dining rooms that would have been lined with stone couches, where the newly initiated could relax with food and drink and socialize with their fellow inductees. Tens of thousands of conical bowls have been found on both the eastern and western hills, indicating that eating and drinking were important components of initiation. “People seem to have either broken their bowl and taken one half, or left the whole thing,” Wescoat says. “I’m convinced these bowls had a key ritual function within the cult, and that you would leave half for the god, or leave it all.”

As the international popularity of the cult of the Great Gods grew, beginning in the fourth century B.C., the enterprising Samothracians continued to invest in new monuments on the western hill in order to promote their sanctuary. During excavations in 2018, the team rediscovered the theater and surviving remnants of what project geologists have identified as locally quarried white limestone and the vibrant purple stone called porphyritic rhyolite that was used for the theater’s seating. They estimate the theater could hold up to 1,500 spectators, who perhaps also visited the sanctuary for Samothrace’s annual festival. Currently, the theater’s steps are the only known ancient path to the Nike monument and the 340-foot-long stoa, or walled portico, the sanctuary’s largest building. “The stoa was one of the main social spaces in the sanctuary,” Holzman says. “It’s the only place that could have accommodated the kinds of crowds that would have gathered to use the theater.”

The western hill was another venue where elite patrons flaunted their wealth and influence by constructing monuments, many of which highlighted the role of the Great Gods as protectors of seafarers. These include the Nike monument and the neorion, a building that housed a massive ship elevated on marble supports. Higher up the hill, along the stoa’s facade, gleaming columns topped with bronze statues competed with other gilt-bronze sculptures for visitors’ attention. Artifacts excavated from the stoa’s foundations and interior hint at the identities of Samothrace’s humbler initiates. Bronze fishhooks recovered from the building were left as votive offerings to the gods in thanks for a safe sea passage, along with terracotta statues, hairpins, and jewelry. There were also magnetized iron rings, which, according to several ancient sources, were given to pilgrims as tokens of their initiation. “One of the appeals of coming to Samothrace and participating in its rituals was membership in a club of Samothracian initiates,” Holzman says. Fragments of plaster unearthed in the 1960s that once adorned the walls of the stoa bear graffiti recording the names of initiates. This imitated the practice of carving names in stone. “Clearly, writing your name down as an initiate was an important element of this,” Holzman adds. The bonds formed on Samothrace endured even after initiates left the island. Throughout the Greek world, people built modest shrines as well as larger religious complexes where they met to share fellowship and worship the Samothracian gods.

As their time in the sanctuary came to an end, initiates could gather near the Nike statue, look down upon the central sanctuary, and admire the stunning vista out to sea. These views were a simultaneous reminder of the journey they had taken to the island and of the experience and benefits of the initiation they had just undergone. “You get a retrospective view of what has happened in your past,” Popkin says, “but you’re also invited to think toward your future and what the rituals will bring at a time yet to come—the protection offered by the Great Gods when you embark back onto the sea.”

The Samothracians and international patrons continued to build and remodel structures throughout the sanctuary for nearly 500 years. At the beginning of the first century A.D., an earthquake necessitated repairs to Arsinoe II’s rotunda and the Hieron. A disastrous event in the early second century A.D., probably another earthquake, razed the monuments of the eastern hill and damaged the walled structure around the Nike statue. Although they repaired the Nike monument, the Samothracians didn’t rebuild on the eastern hill. The final securely dated initiate list was inscribed later that century, and finds such as lamps, coins, and glass suggest that activity continued into the third and perhaps fourth centuries A.D. But it’s unclear when exactly cult rituals at the site ceased. As the Great Gods’ significance waned, Wescoat believes, people stopped coming and the cult gradually died out.

In the coming years, the American team, in collaboration with local archaeologist Dimitris Matsas, plans to investigate a section of the ancient city wall that borders the sanctuary to the east and to consider the island’s broader history. The city itself has never been excavated, but surely holds vital information about the cult’s administration. Like ancient initiates surrendering to the unknown of the mysteries, Wescoat and her team remain open to new interpretations that may arise. “Samothrace asks us to be imaginative in every way,” she says. “All parts of the sanctuary—the place itself, the rites as we know them, the buildings in which they happened—call for us to step outside ourselves and into another world.”

Video: Inside a Greek Mystery Cult

Ancient pilgrims from across the Greek world flocked to the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on the island of Samothrace to be initiated into a popular mystery cult. Using 3-D modeling, a joint team from Emory University and New York University's Institute of Fine Arts is seeking to re-create the journey of these ancient initiates through the sanctuary. These videos simulate part of that route, from pilgrims’ entrance at night, to their steep descent down the Sacred Way toward the ritual buildings where they were likely inducted into the cult, to the stunning vistas of the sanctuary and the sea they would have enjoyed the morning after initiation. To watch additional walk-throughs and learn more about the team’s ongoing excavations, go to samothrace.emory.edu.