Archaeologist Joanna Ostapkowicz of the University of Oxford has spent countless hours combing through documents stored in the two miles of shelves at the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) of the Smithsonian Institution. “It’s an incredible resource,” she says. “The archive is a repository of documents pertaining to archaeology and anthropology by some of the field’s most influential researchers, many of whom were Smithsonian Institution staff.” The records include those related to the Bureau of American Ethnology’s nineteenth-century surveys of mounds in the eastern United States, as well as others covering extensive excavations undertaken by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. Ostapkowicz studies pre-Columbian Caribbean wooden sculptures and was recently at the NAA searching through the files of archaeologist Herbert Krieger, who worked in the Caribbean in the 1930s and 1940s. In a folder marked simply “manuscript,” she made an astonishing discovery. It held a previously uncatalogued document relating to a unique artifact—a two-foot-tall cotton figure known as a cemí, a depiction of a divine or ancestral spirit made by the Indigenous Taíno people who lived in the Caribbean.

European explorers collected many such cemís between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, but this example is the only one known to have survived. It was once thought to have been discovered somewhere in the Maniel region of the southern Dominican Republic and incorporates parts of a human cranium and mandible. Ethnographic accounts suggest that the Taíno consulted cemís as oracles, which might explain why the mouth of this example was woven so it appears to be speaking in an animated manner.

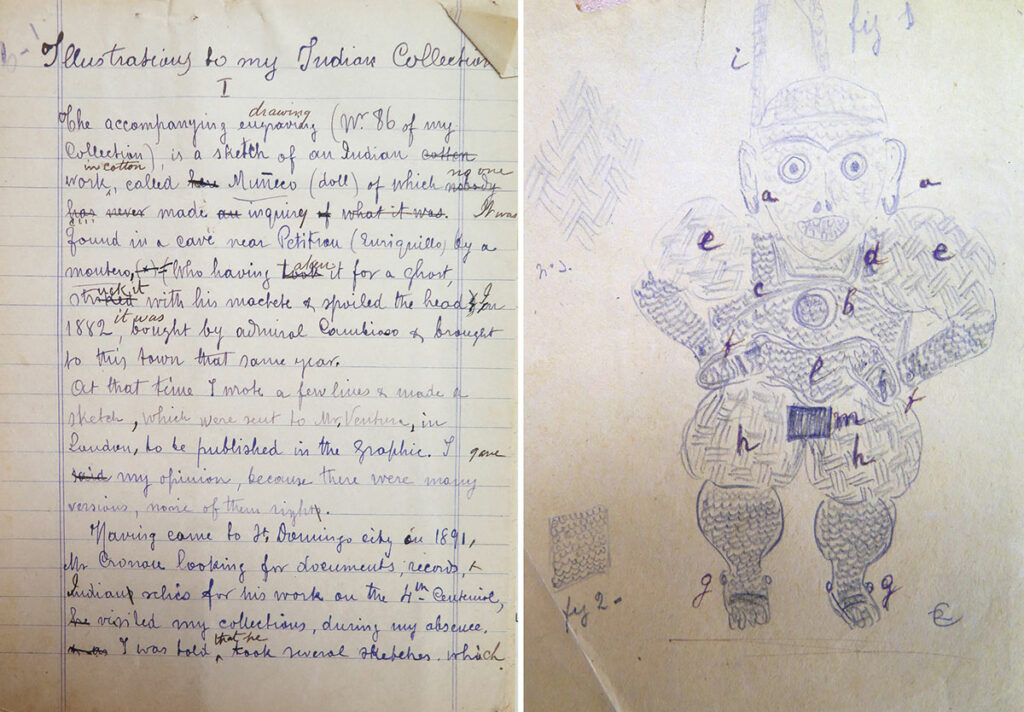

The manuscript Ostapkowicz found is an eight-page description of the cemí written in English by Dominican journalist Rodolfo D. Cambiaso in 1907. His father, Admiral Juan Bautista Cambiaso, a founder of the Dominican Navy, purchased the artifact in 1882. The manuscript clears up the main question surrounding the object’s origins: Cambiaso writes that it was discovered in a cave outside the town of Petitrou, now known as Enriquillo, some 80 miles from Maniel in the southwestern Dominican Republic. “It was found in a cave near Petitrou by a montero [hunter], who having taken it for a ghost struck it with his machete and spoiled the head,” Cambiaso writes. This geographic detail has changed how archaeologists understand the cemí’s history. “Knowing where the cemí was found provides links to regional archaeological sites and helps to anchor the piece in the history of the local cacicazgos, or chiefdoms,” says Ostapkowicz.

The cemí is now housed in the collections of the University of Turin’s Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. Ostapkowicz and anthropologist Cecilia Pennacini of the University of Turin have conducted noninvasive analysis that has revealed the artifact’s internal structure. Previously, they radiocarbon dated it to between 1441 and 1522, before, or shortly after, the arrival of Europeans in 1492. Some early scholars had suggested it was created much later, by escaped African enslaved people.

Ostapkowicz says this newly uncovered information about the cemí highlights the value of spending time hunting down historical records related to artifacts collected before the advent of modern scientific testing methods. “In an instance like this,” she says, “excavating an archive can be as important as excavating a site.” Smithsonian archivist Gina Rappaport says there may be more hitherto unknown records lurking in the NAA’s files. “Many of the materials in the archive have been here for many, many years,” Rappaport says. “We don’t always know the significance of manuscripts, especially in this case where there was no accompanying information. There’s always an opportunity for new discoveries.”