Did a medieval hermit named Guthlac make a plundered prehistoric monument in the Fens of eastern England his home? For generations, scholars inspired by an early eighth-century a.d. account known as the Life of Guthlac have searched for the repurposed barrow where the ascetic—or his sister Pega—is purported to have dug out a cell and private chapel. They have focused in particular on Anchor Church Field in the town of Crowland, which is the site of a medieval abbey. Recently, archaeologists Duncan Wright of Newcastle University and Hugh Willmott of the University of Sheffield undertook the first concerted excavation of the site. “Beginning in the early seventh century a.d., there was a real interest in monuments, especially barrows, being reused,” says Wright. “They were seen as ancestral and as points in the landscape that were very old and very important. Powerful people appropriated them to consolidate their authority at a time that was pretty unstable and used them as reference points for their legitimacy and ancestry.”

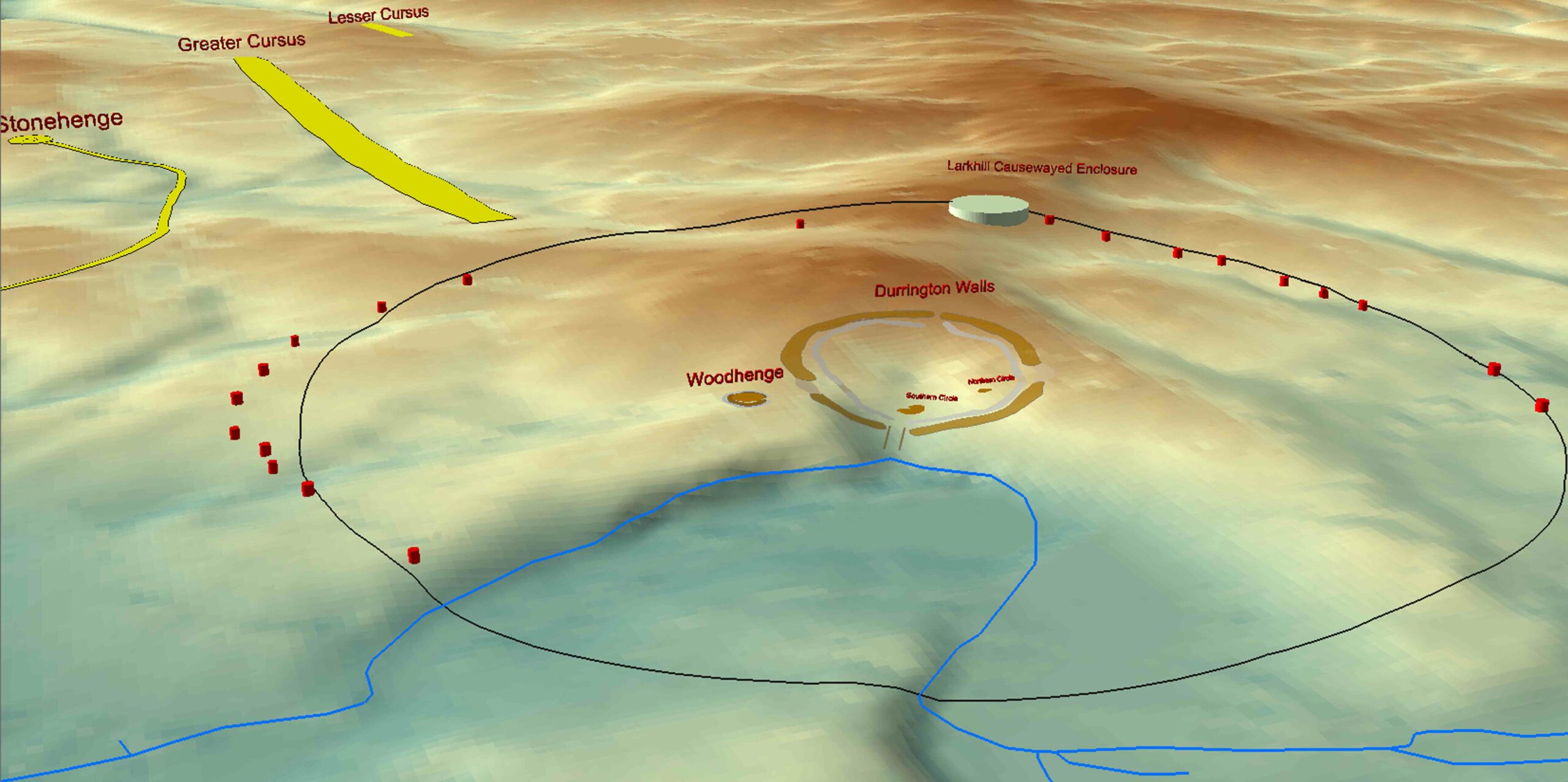

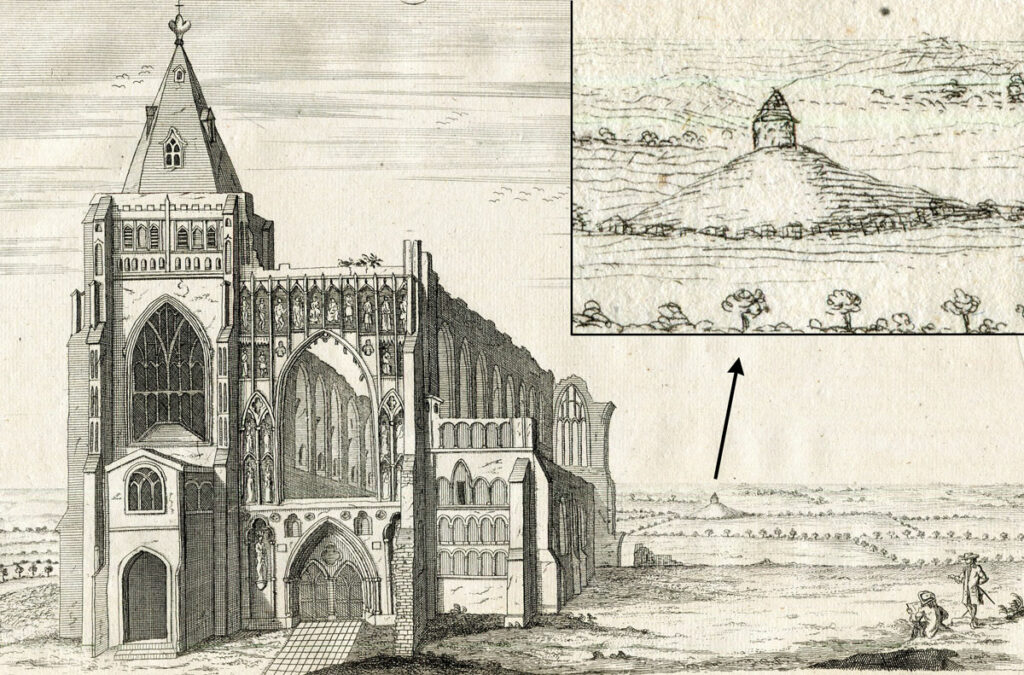

Wright and Wilmott were not able to identify Guthlac’s barrow archaeologically. They did, however, discover an entire landscape of prehistoric monuments, including a previously unknown monumental Neolithic (4100–2500 b.c.) earthen henge and a Middle Bronze Age (1700–1300 b.c.) timber circle. They also found the twelfth-century abbey’s hall and chapel. Crowland Abbey was founded by the Benedictine order in a.d. 971 and became a major pilgrimage site. In 1724, when the antiquarian William Stukeley drew the abbey—and as late as the 1960s—Guthlac’s possible barrow was still visible, although it has now disappeared, the result of centuries of plowing.