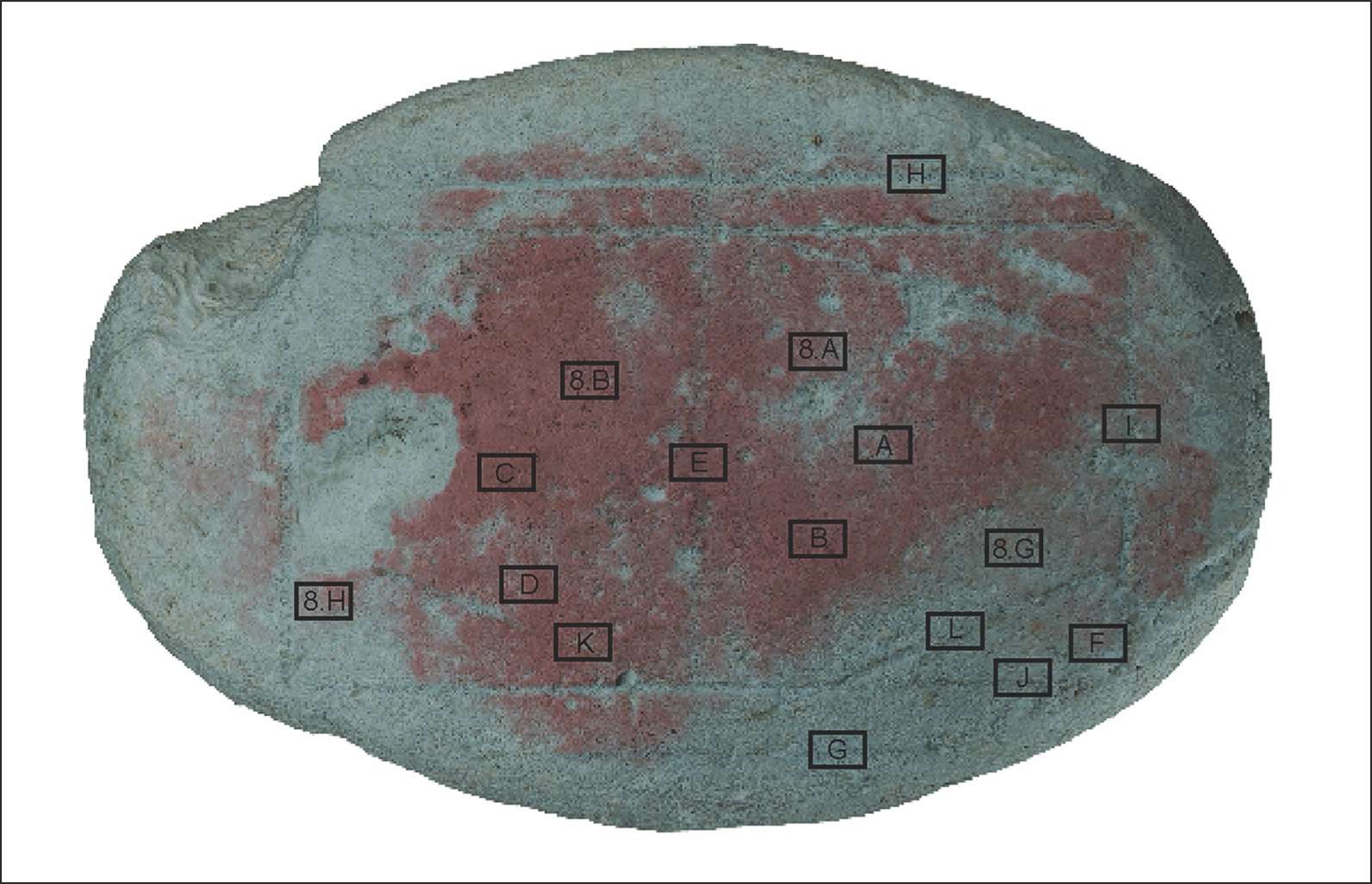

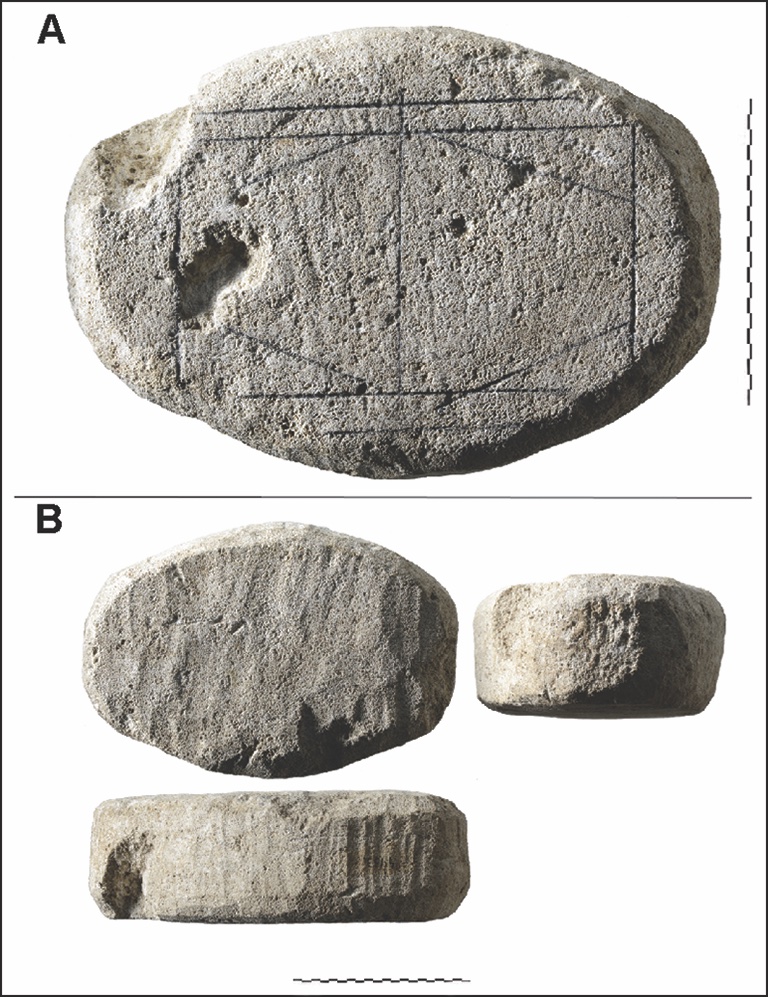

HEERLEN, THE NETHERLANDS—For the first time, archaeologists have used AI technology to help them decipher the rules of an ancient board game, according to a statement released by Antiquity. The small, mysterious stone artifact was originally discovered at the Roman site of Coriovallum, modern day Heerlen, in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. It had sat mostly unnoticed in the collection of The Roman Museum for decades, until it recently caught the attention of Leiden University archaeologist Walter Crist, who specializes in ancient games. “We identified the object as a game because of the geometric pattern on its upper face and because of evidence that it was deliberately shaped,” said Crist. It was nearly impossible, however, to determine how the game might have originally been played. Crist and other researchers turned to AI technology to ascertain how the uneven wear patterns on the stone’s surface might have been related to game play. The team programmed two AI agents to play against each other tens of thousands of times using the stone as a game board and more than 100 different rule sets from known ancient games as a guide, hoping that the computer could crack the code of how the pieces moved. Ultimately, they determined that the wear patterns on the board were consistent with types of blocking games, in which the goal is to block an opponent from advancing, such as tic-tac-toe. These types of games had only been documented in Europe since the Middle Ages, but this new research indicates that they originated 1,500 to 1,700 years ago. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Antiquity. To read about a study of dice from Roman to Renaissance archaeological contexts in the Netherlands, go to "No Dice Left Unturned."