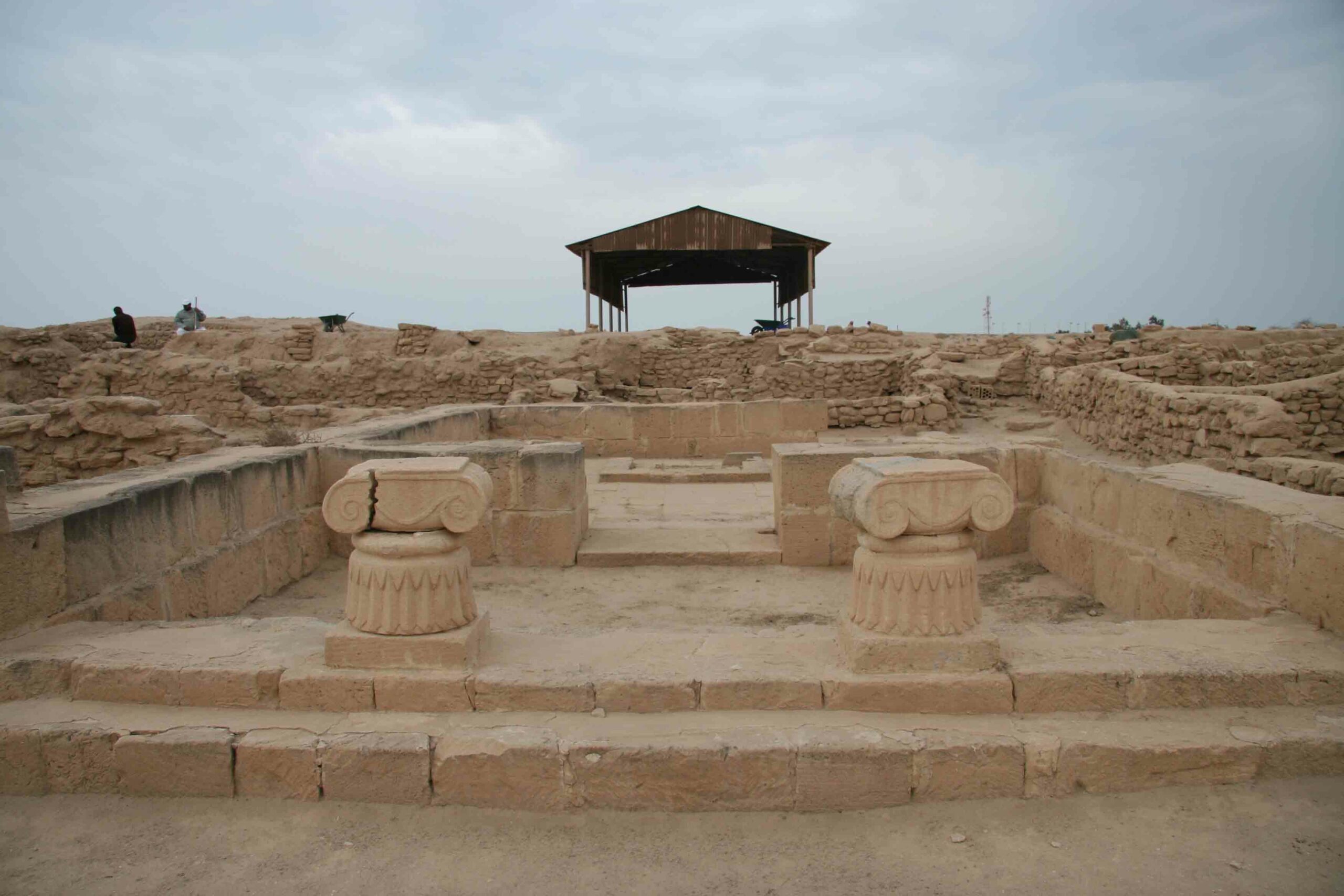

The center of Failaka is a low-lying swampy area that is now the province of mosquitoes and wandering white camels that belong to the Kuwaiti emir. But a millennium ago, this was a three-square-mile pocket of fertile and well-watered plain cultivated by a small community of isolated Christians in a region populated by Muslims. Previous French excavations revealed several villages and two churches, including a possible monastic chapel. A Polish team led by Warsaw-based archaeologist Magdalena Zurek is now busy excavating nearby sites to understand the extent of the settlements that flourished in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D., several hundred years after the faith inspired by Muhammad swept through the region. “We know nothing about Christians on Failaka,” says Zurek, who suspects that a third church lies near her current excavation of a modest farmstead.

Although an old island tradition is that a community grew up around a Christian mystic and hermit, Zurek believes that Christians may have settled in the island’s interior in order to keep a low profile long after others in the region had converted to Islam. The small farms and villages, which were eventually abandoned, may mark the last refuge of Christianity in the region. Yet the larger of the two churches appears to have boasted a lofty bell tower that would have been visible far out to sea, hardly the sign of a community fearful of announcing its faith. There are few written documents of Christian life around the Persian Gulf in late antiquity and the early medieval period, and Zurek hopes that the work at Failaka, together with other excavations of ancient Christian settlements along the Gulf coast, may reveal their hidden history.