There are many extremely challenging places to dig. In Luxor, Egypt, site of a newly discovered 18th Dynasty city (See “Lost Egyptian City”), temperatures often rise above 100°F. At the Yana Rhinoceros Horn site in remote northeastern Siberia, where scientists have found 31,000-year-old baby teeth belonging to a previously unknown human population, it can be as cold as −46°F. Some archaeologists regularly dive to the depths of the ocean. In the field, they can face venomous scorpions and active volcanoes. And there are the dangers of the modern world—the “Big Dig” was conducted in downtown Boston as a new highway was built overhead, and the recent coup in Myanmar has put archaeological work on hold.

But there are few places where more challenges collide than the Judean Desert in Israel and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, home of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The scrolls, the first of which were found in 1947 by a Bedouin shepherd in the Qumran Caves at the north end of the Dead Sea, contain the earliest known copies of biblical books, along with other Jewish religious writings, personal letters, and administrative documents dating from the mid-third century B.C. to the early second century A.D. For the past five years, Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) archaeologists have investigated 580 known caves in the cliffs of the Judean Desert, where the logistical difficulties are unique, explains archaeologist and deputy director of the IAA Theft Prevention Unit, Eitan Klein. “Most of the caves can only be accessed using ropes due to their location in the middle of very steep cliffs,” he says. “The area is very remote and there are communication problems that can cause safety issues.” Compounding these obstacles is the fact that some of the caves are in the occupied territories. According to international law, removing artifacts from these sites is illegal, which raises political and ethical concerns. Looters also pose an ever-present threat.

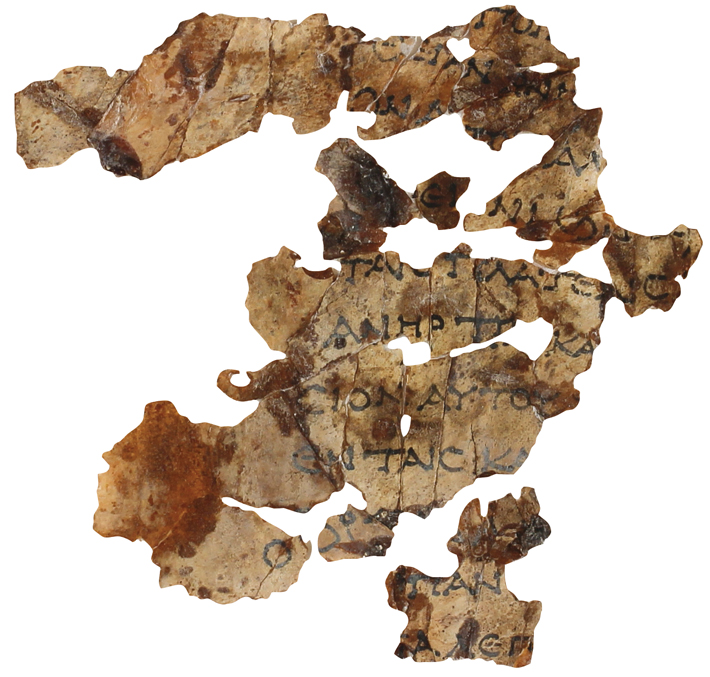

Located 260 feet below the top of a steep cliff, Cave 8 is in one of the Hever Valley’s most remote locations and has proved especially difficult for archaeologists to explore. The cave was first excavated in the 1950s and 1960s, when archaeologists discovered the skeletons of 40 adults and children, the remains of rebels who had fled to the area at the end of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, a Jewish rebellion against Roman rule from A.D. 132 to 135. During the recent campaign, the team unearthed coins bearing Jewish symbols, as well as spearheads and arrowheads, textiles, sandals, and lice combs belonging to the refugees in the cave. They also recovered 70 small pieces of parchment and a few scraps of papyrus, 30 of which of have writing on them, representing the first fragments of any biblical text to be uncovered in 60 years. “They took their most important belongings with them, including the scroll,” says Klein, “and they probably read those prophecies in the last hours of their lives to encourage their souls.”

Except for the name of God, which appears in Paleo-Hebrew, the late first-century B.C. text is written in Greek and consists of missing fragments from the Greek Minor Prophets Scroll, which was found in Cave 8 in the 1950s. Some fragments are blank, while others contain 11 lines from the Book of Zechariah as well as lines from the Book of Nahum. “The fact that the scroll is in Greek tells us that at least some of the rebels were fluent and comfortable using Greek for holy texts,” says Oren Ableman, curator-researcher in the Dead Sea Scrolls unit of the IAA. “It was a real privilege to be the first person in two thousand years to read some parts of this scroll and a joy to find surprising text in the fragments.”

And therein lies another challenge. The Dead Sea Scrolls were written in multiple different languages over hundreds of years and, in the case of the biblical texts, copied by multiple scribes many times over. Sometimes more than one scribe worked on the same scroll. And sometimes mistakes were made by scribes copying the texts, creating even more difficulties. “For example, it was baffling to find the word ‘streets’ where all other manuscripts have the word ‘gates,’” Ableman says. “At first, I thought I might have made a mistake. However, eventually I concluded that the mistake wasn’t mine, but rather was made by a scribe in antiquity.”