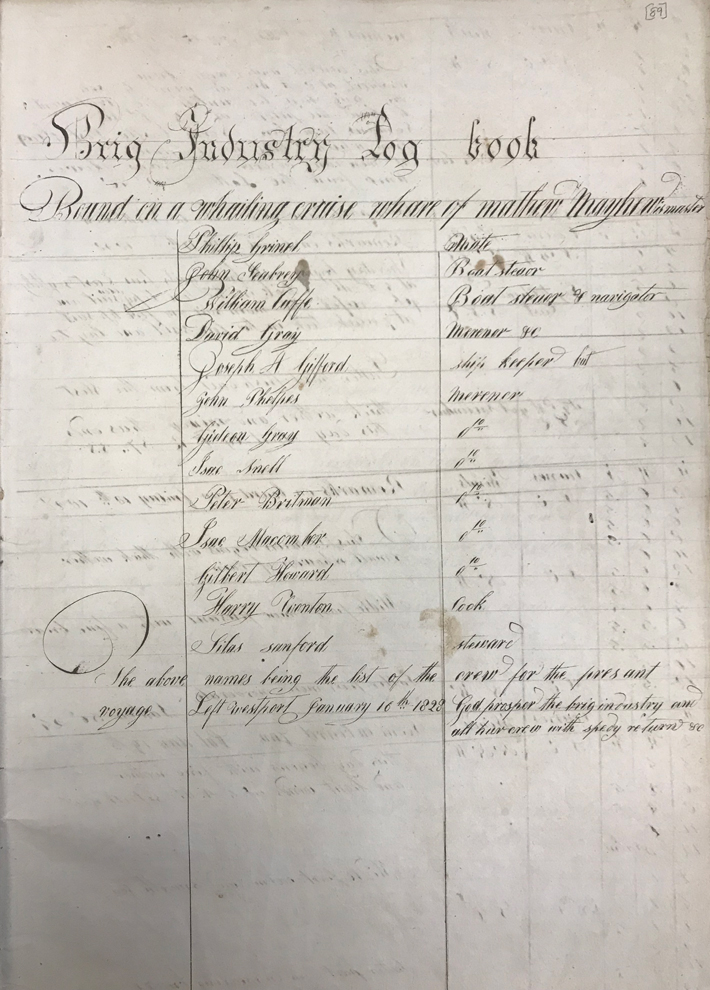

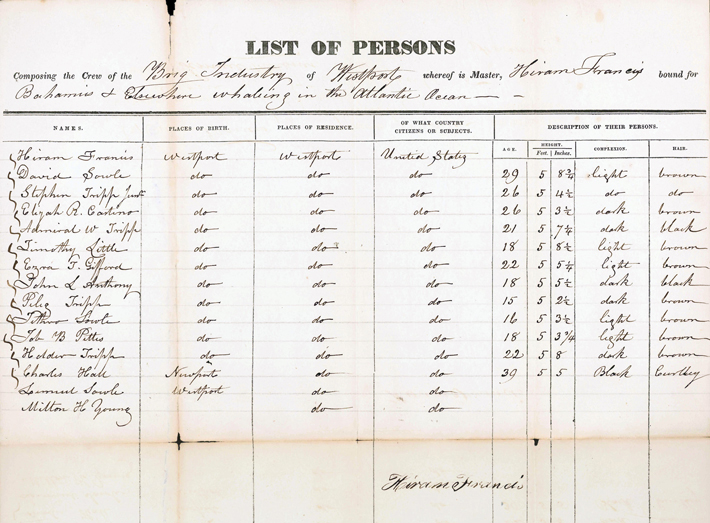

The first few weeks of May 1836 were pleasant ones for the whaling brig Industry. Based in Westport, Massachusetts, the two-masted, 64-foot-long ship had been built in 1815 and launched the next year. Now, two decades into her career, Industry and her crew of 15 men had been out for just over a year hunting sperm whales as far east as the Azores and as far south as the Caribbean. They had built up a store of several hundred barrels of sperm whale oil and were making their way back home when they detoured into the Gulf of Mexico in hopes of topping up their prized cargo.

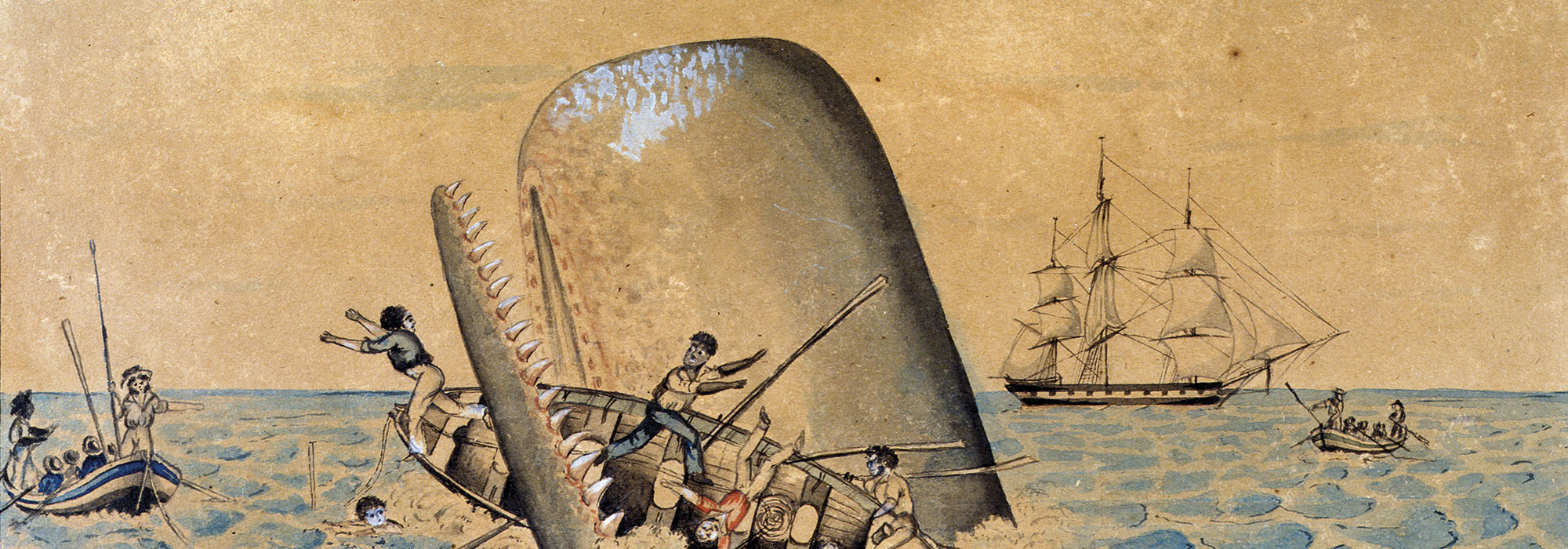

Before the widespread availability of petroleum, sperm whale oil was a valuable commodity. It burned clearly and brightly without smoking, making it ideal for illuminating homes and lighthouses. It was a fine lubricant even at very high temperatures, and was used to oil timepieces, scientific instruments, and industrial machinery. In addition, spermaceti, a waxy substance harvested from sperm whales’ heads, was used to produce the brightest, cleanest-burning candles. And ambergris, an odoriferous material found in some sperm whales’ bowels, was coveted as an ingredient in perfume and worth its weight in gold. “If you were good at killing whales, then you had the ability to make cash,” says Michael Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. “Anyone who participated in the whaling trade in the early nineteenth century could stand to do quite well at it.”

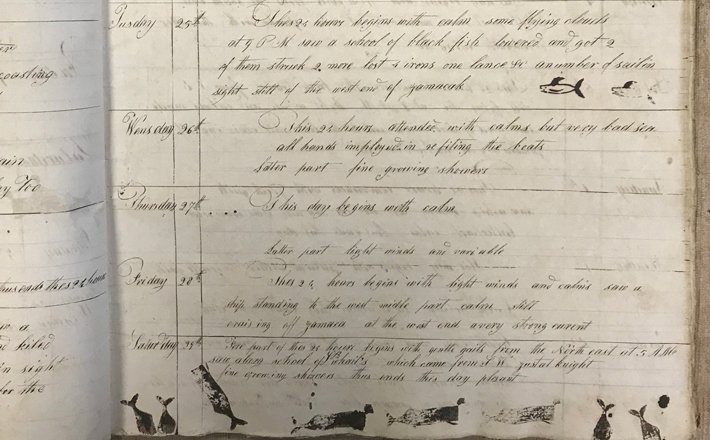

In the Gulf, Industry enjoyed a stretch of fine weather with steady winds and encountered a fellow Westport whaling brig, Elizabeth. The two ships “mated,” in the nautical parlance, and sailed in close proximity for several days. They were a few miles apart when a vicious squall set in on the evening of May 26. “The thunder rolled heavily and in the most terrific tones,” reports a June 20, 1836, article in the New-Bedford Gazette & Courier. “The lightnings flashed vividly and constantly in every direction during the night.”

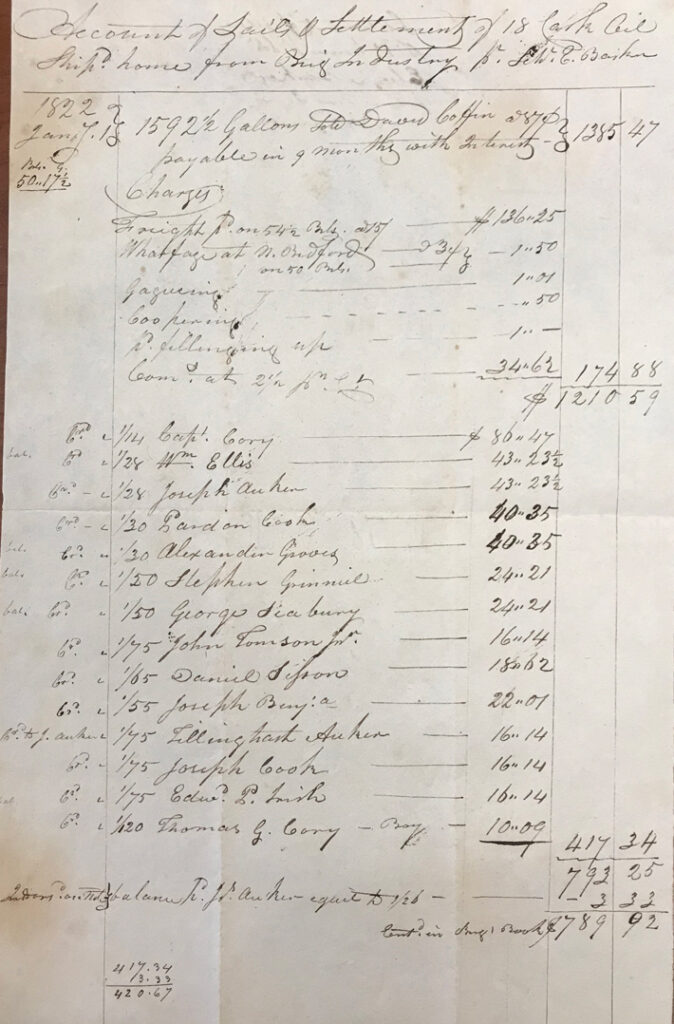

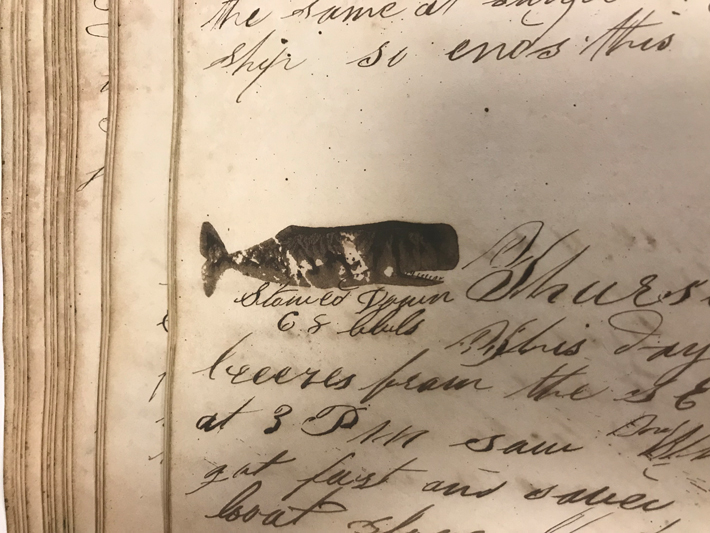

Industry got the worst of it. She was knocked on her side by the wind and waves, and nearly capsized. Both her masts snapped, and all but one of the small boats the crew used to pursue whales were washed away. The only thing keeping her afloat was the buoyancy provided by her precious store of sperm whale oil. The crew piled into their one remaining boat and rowed to Elizabeth, which took them in and sailed back to Westport. Around a week later, a Nantucket-based whaler named Harmony came upon the abandoned Industry and salvaged 230 of her 310 barrels of oil, along with valuable equipment including parts of her sails and rigging, her anchor cable, and at least one of her anchors. No longer buoyed by her full store of oil, Industry slipped under the water and began to drift to the seafloor. Of some 214 whaling ships known to have worked in the Gulf of Mexico between 1788 and 1878, Industry is the only one known to have sunk there.

EXPAND

Maritime Magnate

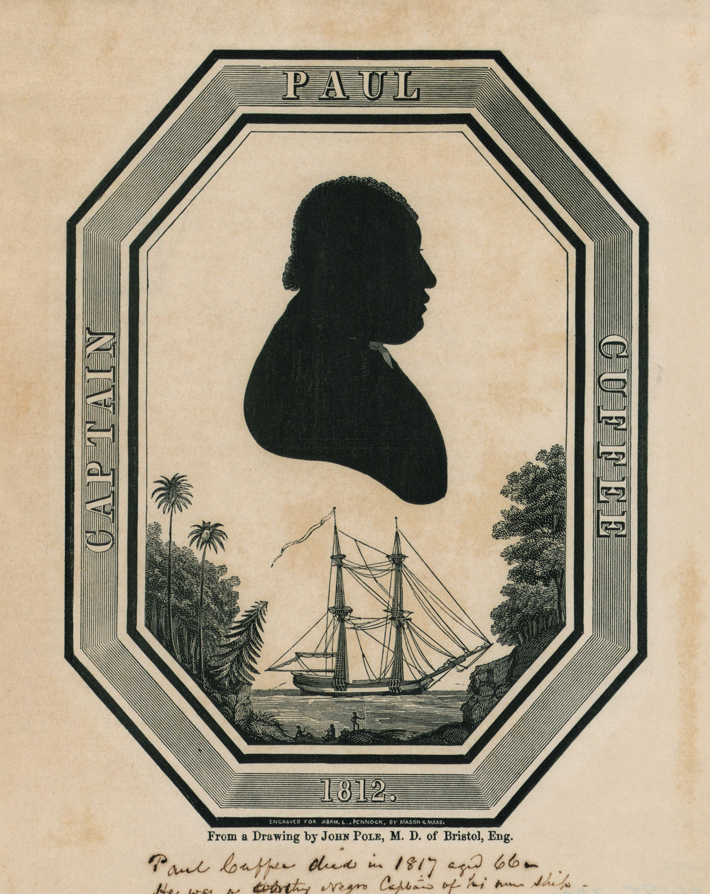

Among African Americans and Native Americans involved in the whaling industry, the most prominent was Paul Cuffe. Cuffe was born in 1759 on Cuttyhunk Island, around 10 miles south of Westport, Massachusetts, to Cuffe Slocum, a formerly enslaved man who had purchased his own freedom, and Ruth Moses, a Wampanoag woman. The family moved to a 116-acre Westport farm in 1767, and Cuffe began his maritime career as a teenager, signing on to a whaleship as a novice. During a subsequent whaling expedition, in 1776, he was taken prisoner by the British Royal Navy and jailed in New York Harbor for three months. Upon his release, Cuffe spent the rest of the Revolutionary War evading a British blockade to ferry supplies by night to Nantucket Island.

At the end of the war, Cuffe began assembling a fleet of ships that he used for whaling, fishing, and shipping. Cuffe himself, or his relatives, captained many of these vessels, and they tended to have all-Black crews. “It was unusual for a Black man to own ships,” says Lee Blake, president of the New Bedford Historical Society and a descendant of Cuffe. “Paul hired men of color who were family members and friends—in that sense, it wasn’t unusual as that is also what white ship captains did.” He developed strong relationships with leading Quaker businessmen, eventually joining the Westport Friends Meeting, and became one of the wealthiest and best-known African Americans in the United States. A dedicated abolitionist, Cuffe was active in efforts to create a settlement for freed slaves in West Africa. When he returned to Westport from a fact-finding mission to the British colony of Sierra Leone just before the start of the War of 1812, his cargo was deemed illegal due to rising tensions with England and his ship impounded by U.S. customs officials. Cuffe attained an audience with President James Madison—perhaps the first African American to have an official meeting with a U.S. president—as well as the secretary of the treasury, who ordered his ship released.

Among Cuffe’s business partners were Isaac Cory Sr. and Isaac Cory Jr., the owners of Industry. In 1802, Cuffe and the Corys built Hero, a two-masted, 75-foot-long vessel, in Cuffe’s Westport shipyard. Originally intended for the merchant service, the ship was later outfitted with a third mast and put to use as a whaling bark. In September 1810, Cuffe and the Corys sent Hero on a two-year whaling mission around Cape Horn. It did not go well. On June 30, 1812, the ship’s captain wrote from Coquimbo, Chile, to share a tale of woe including crew members stricken with scurvy, poor weather, and rotted timbers on the ship, which was ultimately condemned. Nonetheless, the captain managed to send back nearly 700 barrels of sperm whale oil on other ships. Cuffe died in 1817 at the age of 58, but his family’s connection to the Corys continued. Cuffe’s son-in-law, Pardon Cook, who would go on to make 11 whaling voyages in all, was a second mate on Industry in 1819 and 1821. And Cuffe’s youngest son, William, sailed on Industry in 1828 and 1832. Neither, however, was aboard the brig during its fateful final voyage.

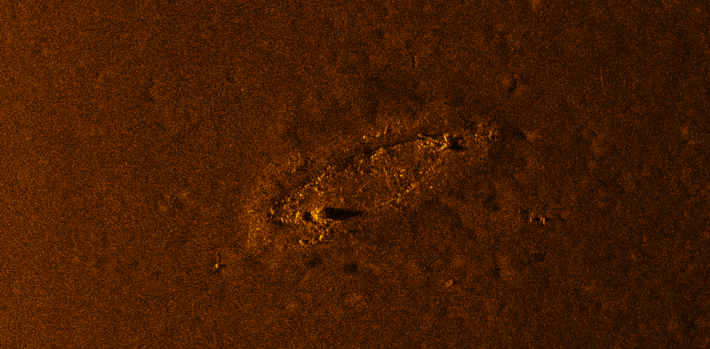

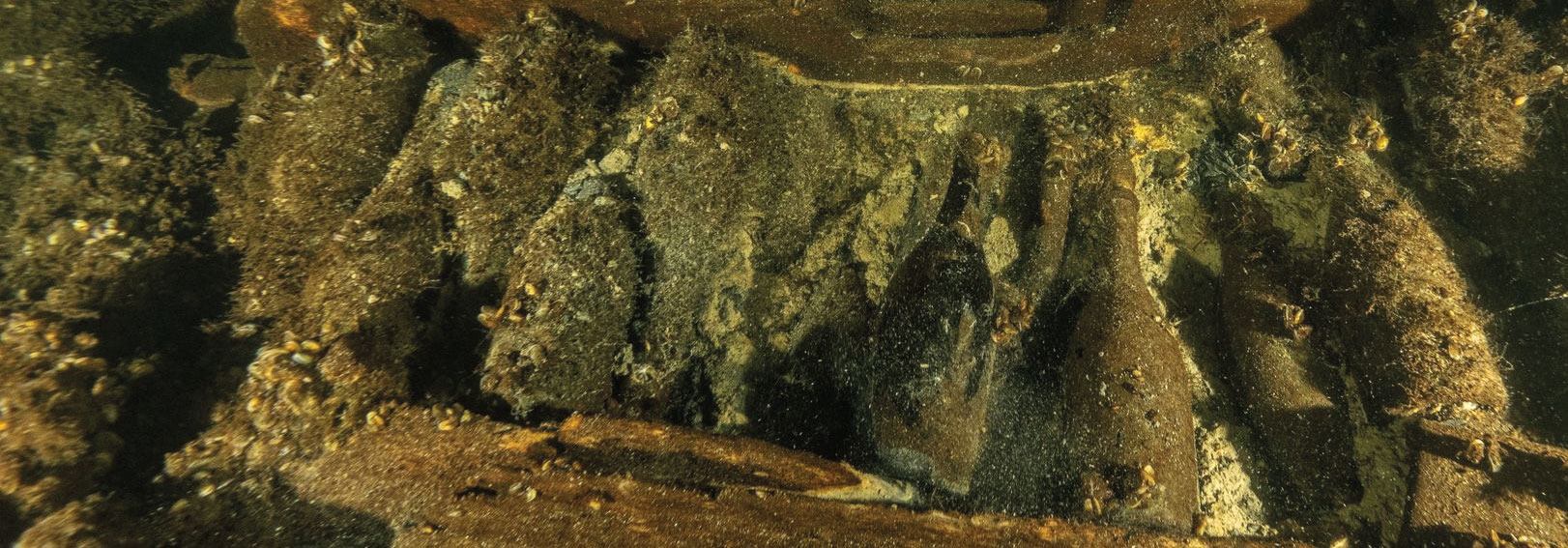

During a 2011 sonar survey of a stretch of the Gulf of Mexico slated for petroleum exploration, what appeared to be a shipwreck was detected around 70 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River and reported to the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). Six years later, a test of an autonomous underwater vehicle captured images of the wreck, which lies 6,000 feet below the surface. The images showed features—in particular, what appeared to be a tryworks, or hearth used to render whale blubber into oil, and anchors of a style dating to the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century—that suggested the wreck might be that of a whaling vessel from the early nineteenth century. In February 2022, a team led by marine archaeologists James Delgado and Michael Brennan of the archaeological firm SEARCH and Scott Sorset of BOEM monitored footage from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration remotely operated vehicle (ROV) as it spent several hours thoroughly documenting the wreck.

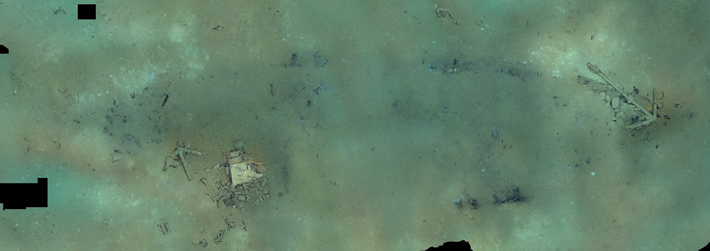

Images from the site collected by the ROV were used to create a 3-D model called an orthomosaic. Using this model, the researchers determined that the wreck’s length is 63 feet and its beam, or greatest width, is 20 feet. Both measurements are nearly identical to those of Industry as recorded in her original certificate of registration. Details of the ship’s structure that could be gleaned from the wreck site also meshed well with what is known of Industry: The wreck is a two-masted vessel with a shallow hull that lacked copper sheathing. The absence of sheathing meant that Industry’s hull was unprotected against the depredations of marine organisms, and the ship’s logbooks include references to her tendency to leak. The location of the wreck, too, some 83 miles north-northeast of Industry’s last known location, as recorded by the crew of Harmony, is consistent with the trajectory of a ship slowly sinking while caught in the Gulf of Mexico’s Loop Current. “We’ve gone back and looked at the data,” says Delgado, “and there are no other known wrecks within 100 miles that would fit.”

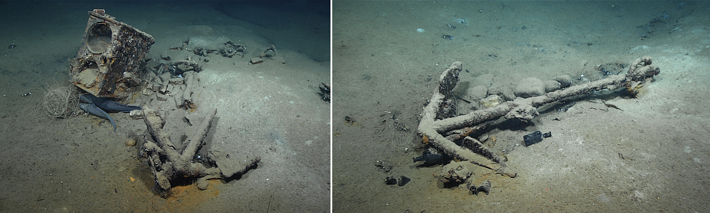

One especially striking feature of the wreck is the dearth of artifacts—which lends support to the theory that it is indeed Industry. “There are things that are absolutely missing that would be there,” Delgado says. “This vessel has all the appearance of having been stripped, which we know was the case with Industry.” The smattering of items that researchers were able to document is also consistent with what would have been aboard Industry. The outline of a wooden cask visible at the center of the wreck’s hold may be the remnants of an oil barrel that remained onboard as the ship sank. A number of glass liquor bottles appear to date to the early nineteenth century. There are three anchors, all of a style known as Old Admiralty Pattern, which dates to the late eighteenth century and was commonly used through the early nineteenth century. Wedged next to one of the anchors is a pane of glass that, Delgado says, would have fit as a stern window in a vessel of Industry’s time. “It was very obvious that we were looking at the form of a vessel from that early nineteenth-century period,” he says.

When the researchers got a close look at what they had initially believed was a tryworks, however, they found it puzzling. A typical whaleship tryworks consisted of a pair of large iron cauldrons embedded in a brick hearth. Once the crew caught a whale, they would flense, or strip, the blubber from the carcass with large hooks and knives, winch it onto the deck in strips, chop it into small pieces, and cook it in the cauldrons over high heat around the clock until the fat was rendered into oil. “It’s kind of like making bacon,” says Judith Lund, a whaling historian and former curator at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. “When you make bacon, you pour off the grease and eat the bacon. It’s the opposite way with whaling: You save the oil, and the stuff that’s left over gets thrown on the fire to boil more blubber.”

Rather than a typical tryworks, the researchers saw an iron stove known as a camboose resting atop a pile of bricks, a peculiar find for several reasons. First, shipboard cambooses known from the archaeological record typically sat on an insulating sheet of lead or iron, but no such metal sheet is evident at the wreck site. Second, unlike other known shipboard cambooses, which tend to have flat surfaces for heating cooking pots, the wreck’s camboose features two large open wells, both of which appear to be fitted with iron pots or cauldrons. For Delgado, this raises the possibility that the camboose was a hybrid tryworks, insulated by a brick hearth and used to render blubber into oil.

EXPAND

Passage to Freedom

In the popular understanding, the Underground Railroad consisted largely of people making their way north over land. In fact, says Michael Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, many, if not most, enslaved people who escaped to freedom did so by boat. “The coastal commerce of the East Coast of the United States before the Civil War was like standing on an interstate overpass and watching the tractor-trailers go by,” Dyer says. “It was constant, with sloops and schooners going up and back all the time. So the potential for enslaved individuals to make their way north on shipboard was high.” Moreover, many enslaved people worked on the waterfront, providing skills and connections that aided in their escape.

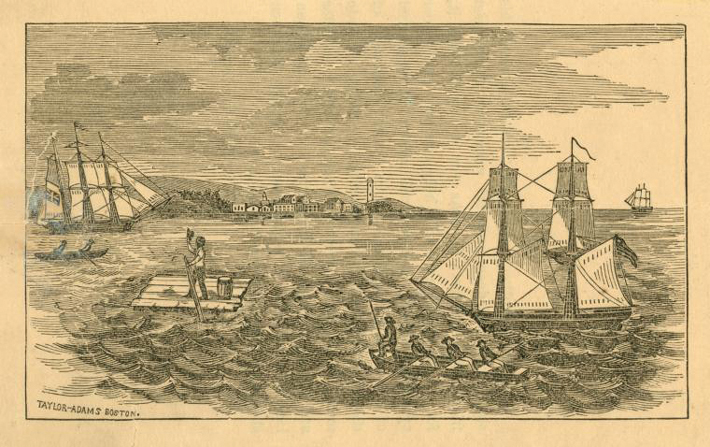

Some people seeking freedom stowed away with full complicity of the crew, as in the case of William Grimes, who fled in 1814 from Savannah, Georgia, to New York on the sloop Casket. The Boston-based crew took a liking to Grimes, who helped load the ship, and they left a space amid the cargo of cotton bales lashed on deck where he could hide during the voyage. Other fugitives, such as Thomas H. Jones, occupied a more precarious position onboard. In 1849, Jones bribed a steward on the cargo brig Bell bound for New York from Wilmington, North Carolina, to hide him in the hold, but was discovered by the captain en route. Fearing he’d be sent back into slavery, Jones jumped ship in New York Harbor, paddled toward shore on a makeshift raft, and was rescued by sympathetic boaters.

Southern authorities attempted to prevent maritime escapes by passing laws requiring a thorough search of all northbound ships and by fumigating them with a foul mixture of pitch, tar, vinegar, and sulfur. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which forbade aiding and abetting people fleeing enslavement, put a legal onus on captains and crew. While they often obeyed the letter of the law, they frequently did little to help return fugitives to captivity. Newspapers in northern ports developed a standardized text that ship captains could publish as legal notice when they delivered a fugitive to free soil. For example, in the April 20, 1797, edition of The Medley or Newbedford Marine Journal, William Taber, captain of the sloop Union, posted an advertisement stating that he had discovered a stowaway “who had concealed himself unbeknown to me” after leaving Virginia for New Bedford. “It appearing inconsistent for me to return, the wind being ahead, I proceeded on my voyage and landed him in this Port,” Taber writes. “He calls himself JAMES, is about 27 years old, and says he belongs to Mr. Shacleford, a Planter, in Kings and Queen’s County, Virginia. Any person claiming him, will know by this information where he is.” As these papers tended to be weeklies, escapees were afforded time to move on before anyone could apprehend them.

Once escaped slaves were in the North, signing onto a whaling expedition was an appealing option for some who wanted to be certain they weren’t caught and re-enslaved. “If a man made it to New Bedford or wherever, he could sign onboard a whaler because they didn’t care who you were,” says Dyer. “As long as you didn’t have tuberculosis and weren’t a drunkard, they’d hire you. And once you joined a whaler, you were out of sight, out of mind, for years. Nobody is going to be able to track you down if you’re someplace in the Indian Ocean or the North Pacific.”

However, the pots in the camboose don’t appear large enough to have handled the amount of blubber that the crew of Industry would have had to process. The crew would also have needed a stove to cook food. There are accounts of whaling crews occasionally snacking on doughnuts fried in whale oil and pork rind–like “cracklings” fished out of the rendering cauldrons, but this would hardly have been sufficient to live on. An alternative scenario, says Delgado, is that the camboose was used as the ship’s cookstove, while a brick hearth held cauldrons that are missing—either removed by Harmony’s crew, or lost in the storm or during the ship’s journey to the seafloor. The camboose might have been adjacent to this tryworks and come to rest on the bricks as the wreck settled. Nonetheless, suggests Delgado, the wreck appears to be the lost whaling ship. “We’ve got a wreck in the right area, the size fits, the age fits, the rigging fits,” he says. “We’ve looked at the other targets around it, and there’s nothing quite like it. So, in the absence of a bell or something with the ship’s name on it, we believe it is likely Industry.”

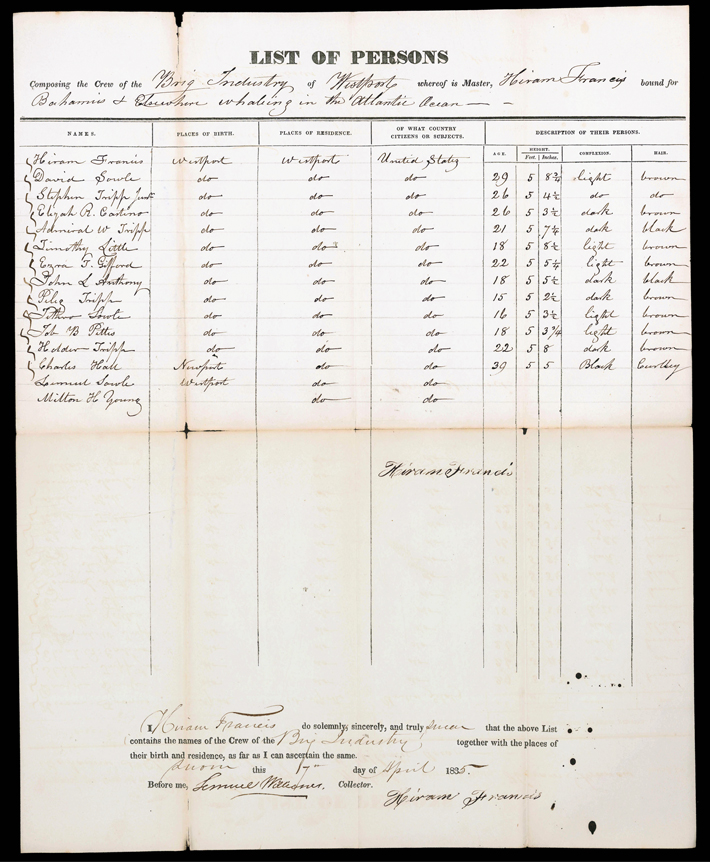

Like other New England ports such as New Bedford, Nantucket, and New London, Westport grew wealthy from its involvement in the whaling industry. Unlike these other ports, however, which by the 1830s were home to larger whaleships that embarked on multiyear voyages to the Pacific or Indian Ocean, most of Westport’s fleet consisted of smaller ships such as Industry that went out for at most 14 months or so and usually stuck to the North Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico. “Westport crews were, generally speaking, from the immediate community, and they all knew each other and were often related to each other,” says Dyer. For instance, according to Robin Winters of the Westport Free Public Library, Hiram Francis, who began Industry’s final voyage as captain, was a half brother of George Sowle, captain of Elizabeth, the ship that rescued Industry’s crew. There was also at least one pair of brothers aboard Industry when it got caught in the storm: David Sowle, who began the final voyage as first mate and appears to have taken over as captain along the way, and his younger brother Jethro.

New England whaling crews, including those from Westport, regularly included African Americans, Native Americans, and those with mixed heritage. (See "Maritime Magnate") In part, this was because whaling ports were heavily Quaker communities with strong humanitarian, antislavery leanings. Whaleships were also relatively meritocratic workplaces, with crew members by and large rewarded for their abilities without regard to their ethnic or racial background. “This is one of the few pre–Civil War opportunities for African Americans to be equal, to be accepted on the merits of who they are as a person and the work they can do as opposed to being judged by the color of their skin,” says Delgado. “If you worked hard, and you worked with others, then you got equal pay. You don’t get different pay because you’re Native or African American.”

Industry’s crew lists provide evidence that a significant portion of her crew over the course of her career was African American. While these lists don’t directly identify individuals’ race or ethnicity, they do specify their physical traits, describing their skin as “light,” “dark,” “mulatto,” “coloured,” “brown,” or “yellow” and their hair as “brown,” “black,” “wooly,” or “curley.” It appears that at least one crew member on Industry’s final voyage, named Charles Hall, was African American.

When the ship foundered in the storm, Hall would have faced peril not only from the turbulent Gulf, but also from local authorities if he were to wash up in a nearby southern port. There, Hall might have been targeted by ordinances known as seaman’s laws, according to which free Black people could be thrown in jail and, if they failed to pay for their upkeep, could be sold into slavery. For Dyer, the contrast between the freedom Black sailors enjoyed on whaleships and the potential threat to their liberty on land is striking. (See “Passage to Freedom”) “If they’re onboard a Yankee whaler, they’re carrying a seaman’s passport and protection paper,” he says. “This means that Black sailors in foreign ports were protected under the full weight of American sovereignty, but they could be arrested in South Carolina or New Orleans.” Fortunately for Hall and the rest of the crew, Elizabeth was available to take them home to Westport. Once there, several of those who had weathered the storm on Industry, including Hall, headed back out to sea within the next few months. After all, there were more whales to hunt and plenty of money to be made.

Slideshow: A Whaleship Lost in the Gulf

The whaling brig Industry, which was caught in a fierce storm on the evening of May 26, 1836, is the only whaling vessel known to have sunk in the Gulf of Mexico. Just over a decade ago, researchers using sonar located a wreck 6,000 feet underwater and 70 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River. The wreck was later photographed by an automated underwater vehicle, and in February 2022 it was thoroughly investigated by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration remotely operated vehicle. Maritime archaeologists believe the wreck is likely to be Industry. (Credits are included with each image. Thank you to the New Bedford Whaling Museum for permission to use several images.)