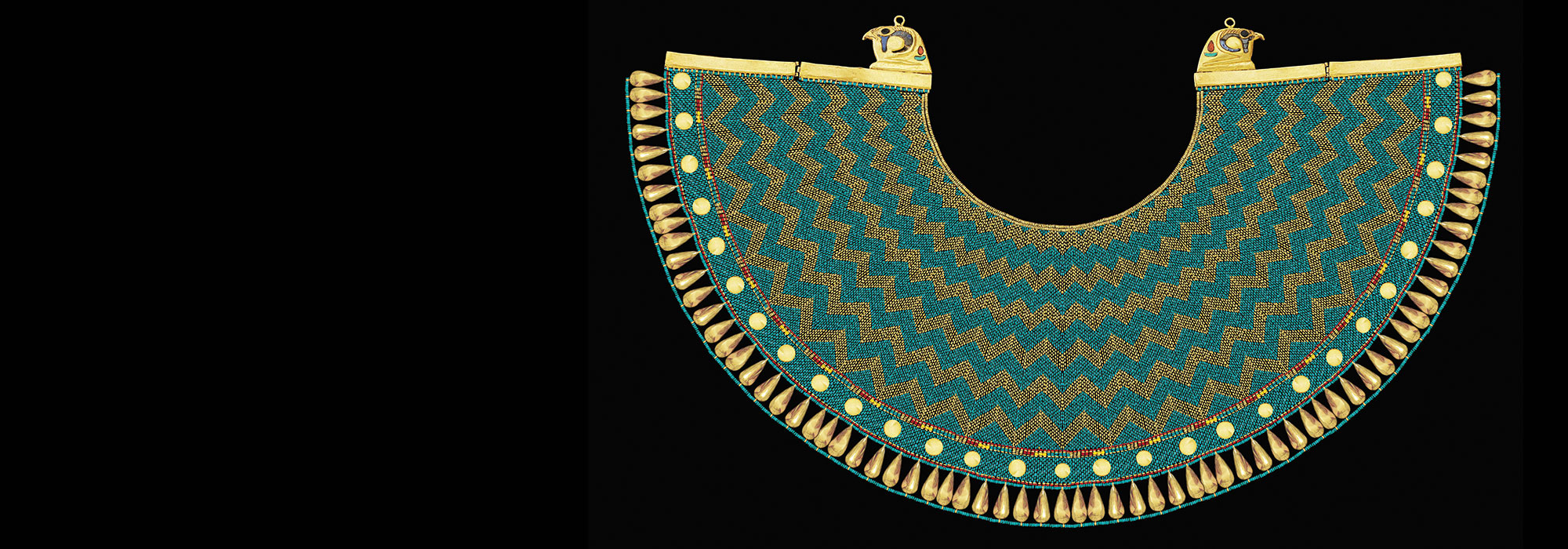

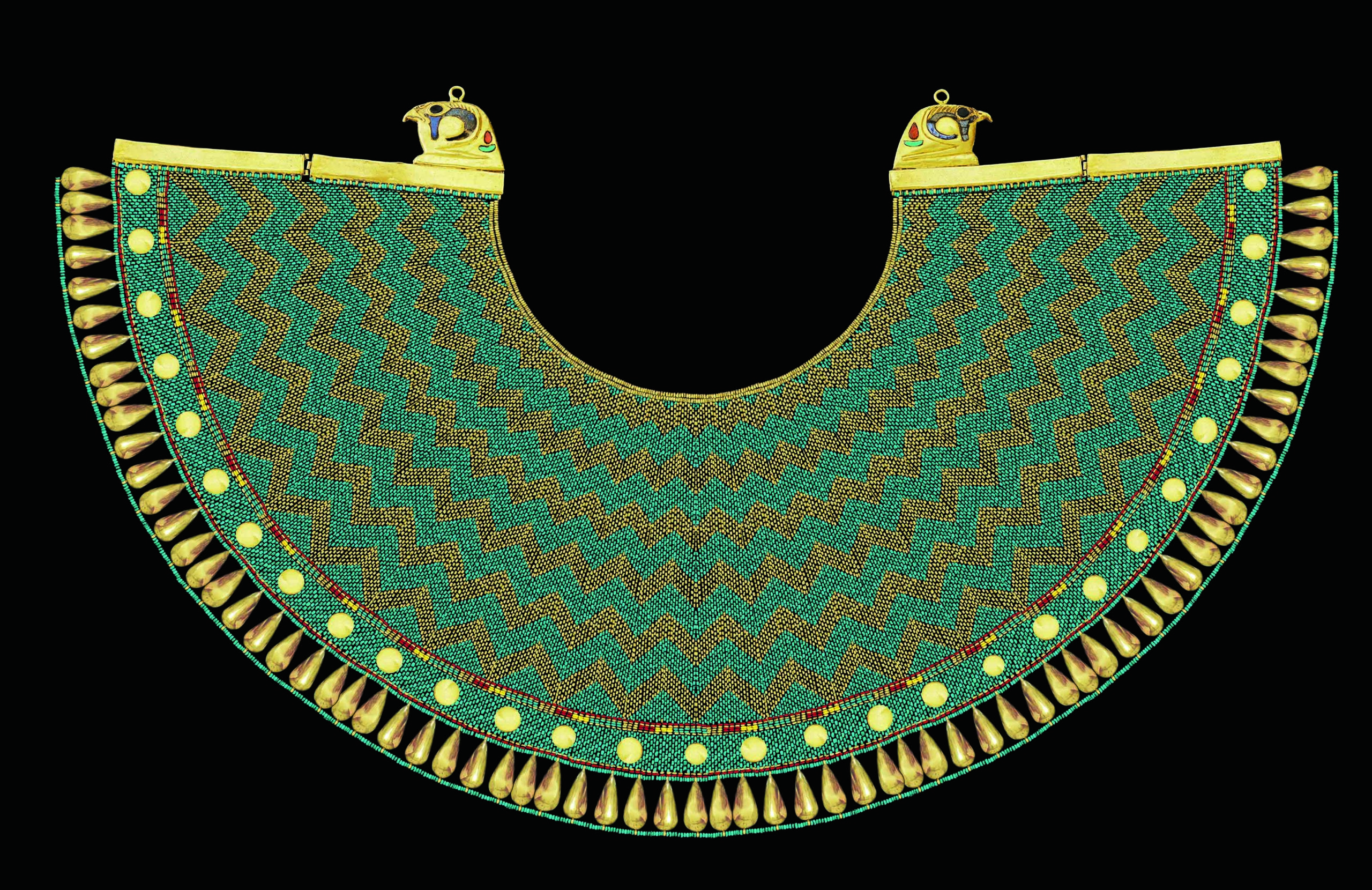

Below the whole group and at the lowest level before reaching the skin, was a bib-like Collarette composed of fine green faience & gold bead matting having a zigzag pattern.…This bib covers the whole of the upper part of the chest as far as the clavicles.—Howard Carter, November 15, 1925

Three years, almost to the day, after archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.) in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, he removed the pharaoh’s mummy from its coffin and unwrapped a layer of linen bandages. Underneath, he saw a splendid collar on the chest of the young king where it had been placed more than 3,000 years before. Photographs taken by excavation photographer Harry Burton nearly a year later show the collar still in place when the mummy was returned to the coffin. But when it was X-rayed in 1968, the collar was gone, and the mummy was badly damaged where the piece had once lain. For the past seven years, Egyptologist Marc Gabolde of Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 University has been trying to find the collar—or what remains of it—and discern whether Carter took any part of it himself. “When I began my book about Tutankhamun a decade ago, I realized I had to address the question of objects that were diverted by Carter,” Gabolde says.

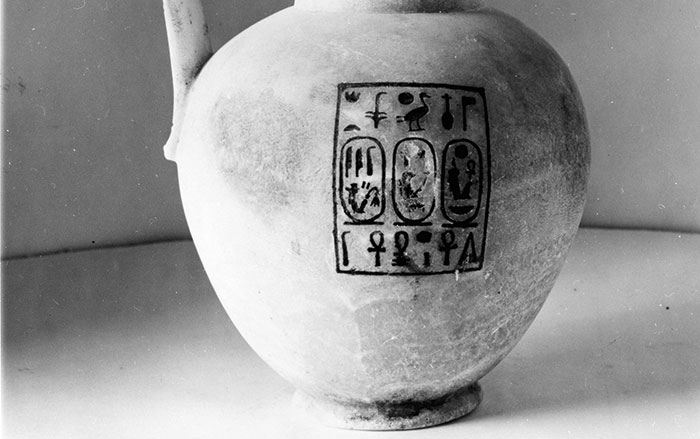

Some early excavators in Egypt had permission to take a selection of artifacts back to their home countries, a system called partage, or “division,” but Carter had no such agreement with the Egyptian government for Tutankhamun’s tomb. Everything he found was supposed to remain in Cairo to be stored or displayed in the museum there. Carter died in 1939, and his niece, Phyllis Walker, was responsible for disposing of his property. The auction house Spink & Son prepared a probate list with valuations of artifacts found in his collection, 20 of which were identified as having belonged to Tutankhamun. In 1946, Walker gifted some of these artifacts to King Farouk of Egypt, who in turn gave them to the Cairo Museum. “They could not be returned, per se, because they were never supposed to have left in the first place,” says Gabolde. Other objects from Carter’s collection had already been sold by Spink, including—almost certainly, says Gabolde—other artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb.

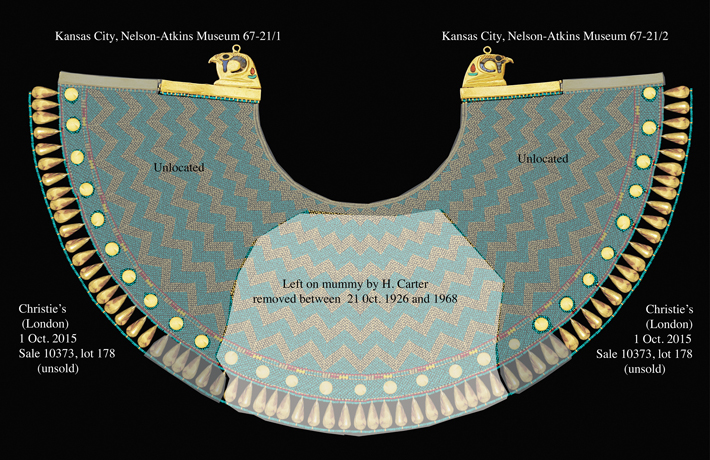

In 2015, Gabolde saw a gold necklace that came from a private collection listed for sale by the auction house Christie’s in London. It had been offered elsewhere five years before, but the jewelry didn’t sell in either instance. “When I first saw the image of the necklace a few weeks before the auction, its workmanship struck me as familiar,” says Gabolde. After a year of research, he concluded that the piece is composed of gold beads from the very collar that Carter had seen in 1925 on the pharaoh’s mummy. Gabolde notes that the beads had been restrung into what he calls a “fantasy necklace,” fashioned from pieces of the original jewelry to create something entirely inauthentic. His research next led him to two gold and faience hawks in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. Gabolde believes these artifacts, too, came from Tutankhamun’s beaded collar—they had been purchased by the museum in 1967 from a collector who had received them from a surgeon and amateur Egyptologist who had, in turn, obtained them from Carter.

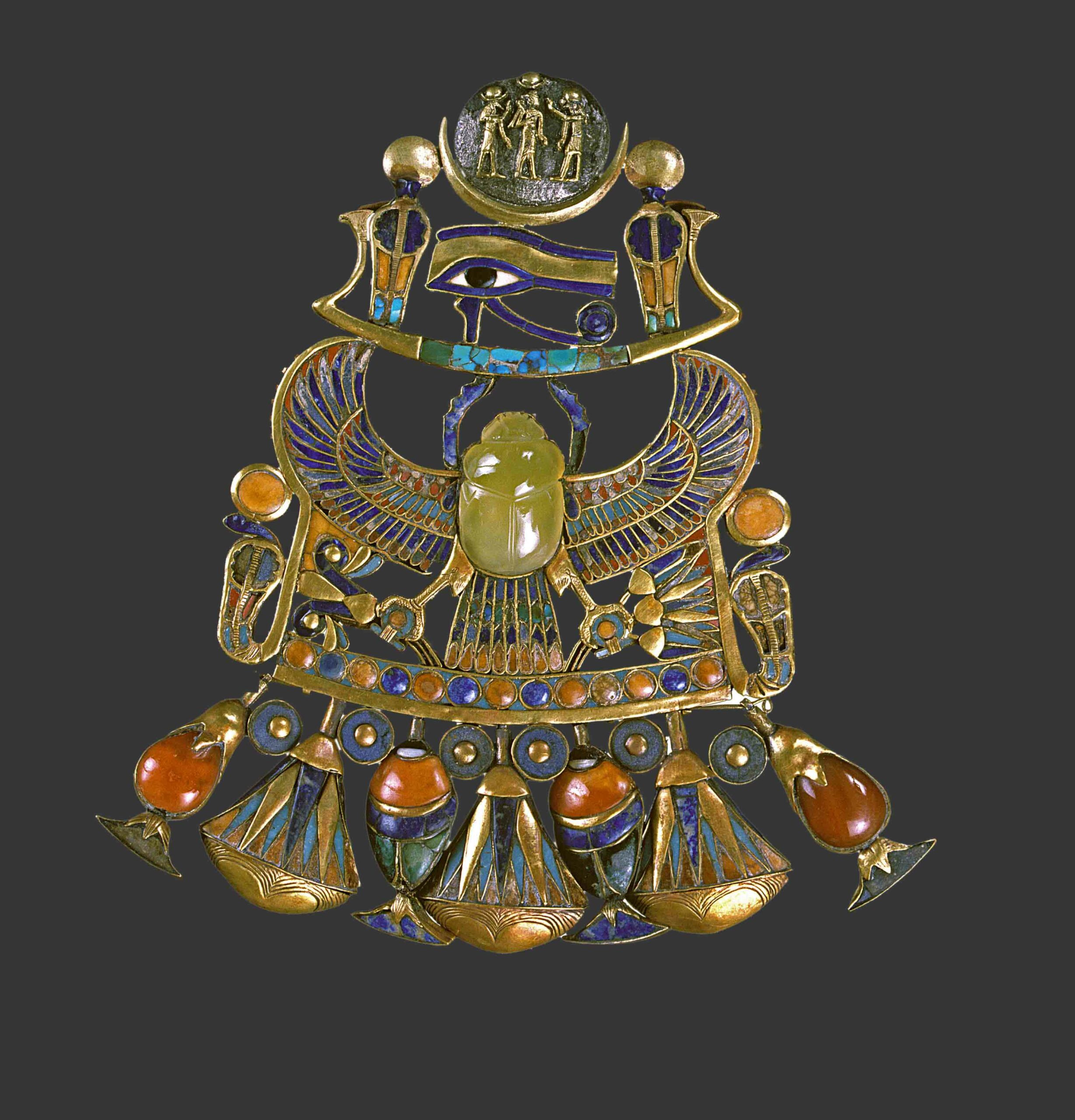

Pieces of the collar are not the only artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb once in Carter’s possession to have landed in museum collections. Gabolde has shown that others include a gold and blue glass necklace now in the British Museum and another fantasy necklace in the Saint Louis Art Museum made of beads from a headdress purchased from Spink in 1940. There are likely still more; in 2010, the Metropolitan Museum of Art sent 19 artifacts that were shown to have come from Tutankhamun’s tomb back to Egypt.

For his part, Gabolde was startled to locate objects in collections that others had not. “What surprised me was to find a little more than what had been identified by previous researchers and to be able, for some objects, to give the exact correspondence with Carter’s files,” he says. “Several researchers had already found that objects from the Carter files did not have matching numbers in the Cairo Museum records, but their investigations hadn’t gone so far as to examine what was in other museums in Europe or America. The starting point for these investigations has often been the Spink & Son probate list, but this is unfortunately not complete.” When asked why Carter would remove the objects in the first place, Gabolde says, “Carter was a person of the nineteenth century and was very impressed by British aristocracy and wanted Egypt to remain as it had been under Queen Victoria. He didn’t realize Egypt had changed.”