Archaeologists rarely unearth the remains of large predators such as leopards, lions, and bears. But University of Haifa archaeologist Ron Shimelmitz and his colleagues wondered if, by looking at a large number of sites over thousands of years, they could identify evidence showing that ancient people hunted these fearsome creatures. The team reviewed reports of animal remains discovered at sites in the southern Levant dating from 25,000 to 2,500 years ago. They found that the frequency at which leopard, lion, and bear skeletal remains were found changed over time. Leopard bones were relatively numerous at sites dating to the Neolithic period (9700–4700 B.C.), but were virtually nonexistent in later Copper and Bronze Age (4700–1200 B.C.) settlements, where there were more bear bones and many lion bones. “If these bones were the result of random encounters with predators,” says Shimelmitz, “then you wouldn’t expect to see a pattern.”

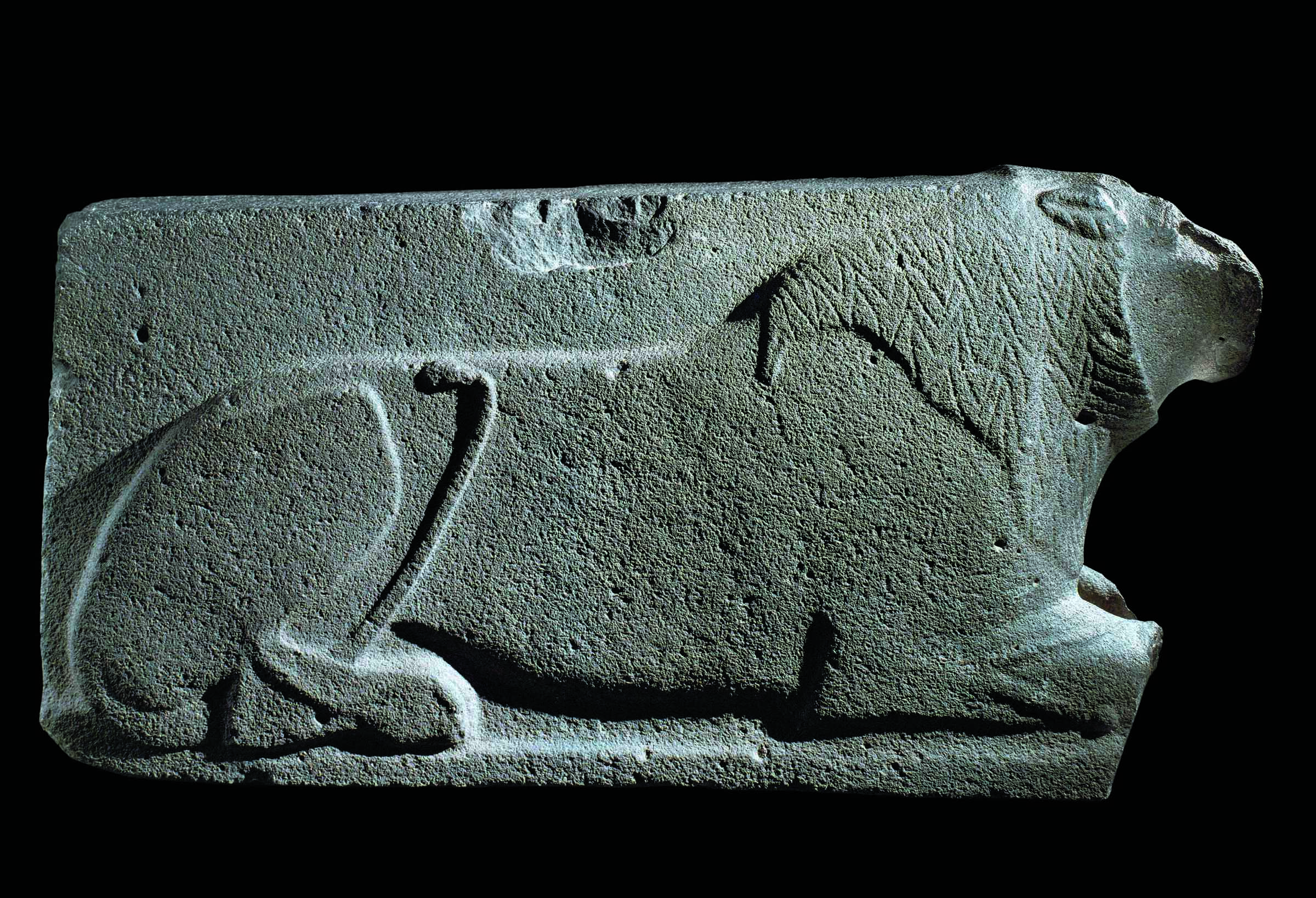

The researchers hypothesize that the shift reflects the changing symbolic importance of large predators over time. As people first came together in permanent settlements in the Neolithic period, the solitary, nocturnal leopard, a symbol of the dangerous natural world, may have acquired special significance. Later, as societies grew more complex and social hierarchies developed in the Copper and Bronze Ages, the lion and the bear may have become more important as symbols of authority. The team found that lion head and toe bones were particularly well represented at sites dating to the Bronze Age (3700–1200 B.C.), leading them to speculate that the bones are what was left of pelts. “Wearing pelts allowed people to prolong the symbolic value of the lion hunt for years,” says Shimelmitz.