Life would have been hard for most Chinese immigrants in the American West, especially itinerant workers. Ryan Harrod of the University of Alaska Anchorage recently excavated 13 sets of skeletal remains from a Chinese graveyard at Carlin, Nevada, the district terminus for the Central Pacific Railroad. Such graves are rare, as remains were usually sent home to China. The individuals buried at Carlin had several signs of poor nutrition. They also showed evidence of years of grueling manual labor: highly developed muscle attachment points and joints with signs of deterioration. There was also blunt force trauma, from broken bones to a fatal head wound, which reflects the constant threat of physical violence they faced. “In general, just being Chinese at a time when there’s anti-Chinese sentiment in a fairly rural community in the West probably wasn’t that good a situation,” says Harrod.

Daily life might have been better in more established Chinatowns, but the Chinese still found themselves disadvantaged. “They were often denied access to public healthcare facilities and denied treatment by doctors,” says archaeologist Sarah Heffner, who examined seven collections of Chinese-American healthcare-related artifacts for her dissertation at the University of Nevada, Reno. In the collection from Lovelock, Nevada, at the Nevada State Museum, Heffner found more than 100 health-related artifacts. She found herbal materials used in Chinese medicine, such as turtle carapace, cuttlefish cuttlebones, snake bones, and bobcat bones (perhaps a local substitution for tiger bones, prized in traditional Chinese medicine).

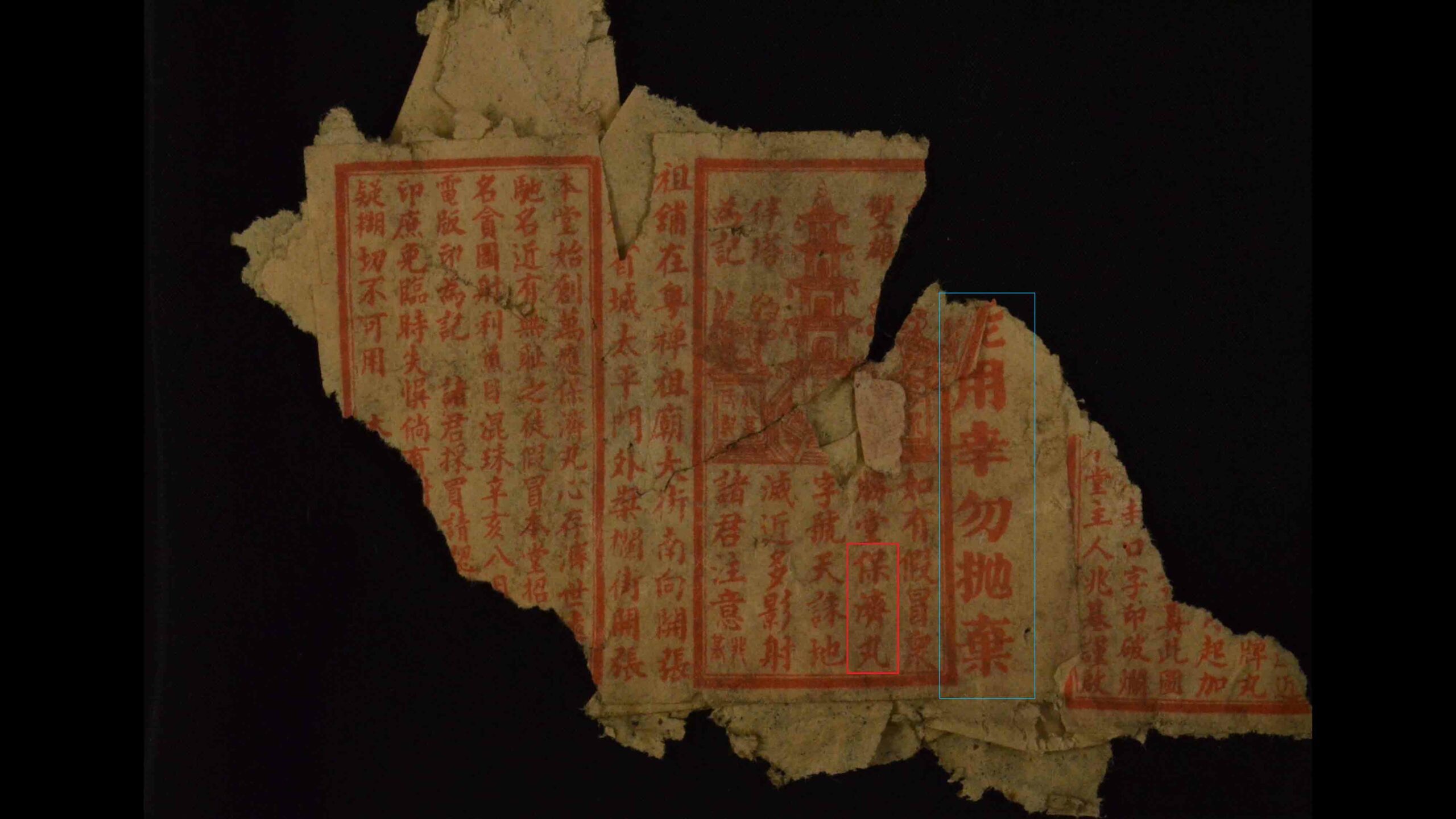

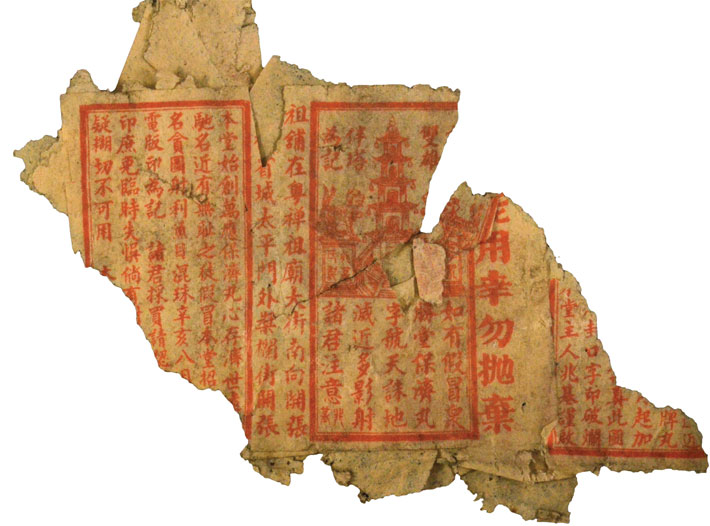

There was also packaged Chinese medicine. One embossed single-dose vial had the name of a drugstore in Hong Kong and specified that it contained “deer’s tail,” “testes and penis of ursine seal,” and “tonify the kidney pills”—all associated with kidney health and treatment of impotence or premature ejaculation. The paper wrapper from another container was labeled “bao ji wan,” or “pills of relief,” and had a written warning that any attempts to copy the contents would result in a curse on the counterfeiter’s family.

In the Lovelock collection Heffner also saw Euro-American medicines, primarily bottles containing popular patent medicines such as Sloan’s Family Liniment and Perry Davis’s Vegetable Painkiller. Like the packaged Chinese medicines, these purported cure-alls would have been cheap and practical. “The list of ailments they treat goes on and on and on,” says Heffner. The use of both traditional Chinese treatments and American patent medicines is indicative of a lack of access to more formal healthcare. Not to mention that American patent medicines had a certain popularity because they could be up to 40 percent alcohol and exempt from taxes on spirits.

Single-dose vials like the ones that Heffner studied are common at Chinese sites in the West. Ray von Wandruszka, a chemist from the University of Idaho, is the first to look inside such vials. “Some still had stuff in them,” he says. One vial from Market Street Chinatown in San Jose contained a bright red residue that turned out to be cinnabar, a sulfide of mercury used to treat infections in Chinese medicine. “It’s really toxic, by the way,” von Wandruszka says. Another contained magnetite, used to make an elixir to “anchor and calm the spirit—relieve restlessness, palpitations, insomnia, tremors—improve hearing and vision—combat chronic asthma,” according to a modern sales pitch. These treatments are known as “stone drugs,” pure or mixed mineral powders, and many are still available online today.