The two hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, might be the most heavily documented and studied in history. There are eight official investigations, from a Naval Court of Inquiry to a Joint Congressional Committee, reams of records, and enough books, oral histories, documentaries, and feature films to fill a library. Yet there are still things that can be learned about the morning when 350 Japanese warplanes killed 2,403 Americans, wounded another 1,104, and sank or severely damaged 21 ships in a coordinated attack on military sites around Oahu, Hawaii.

A number of factors have obscured details—big and small—from that day. For example, the surprise of the attack complicated eyewitness accounts. Secrecy shrouded the active war effort on both sides. And, in the aftermath, the United States rushed to rebuild its naval power in the Pacific with the greatest maritime salvage project in history, which returned all but three of the damaged ships to service. This effort begins to explain why there are few archaeological sites directly tied to December 7.

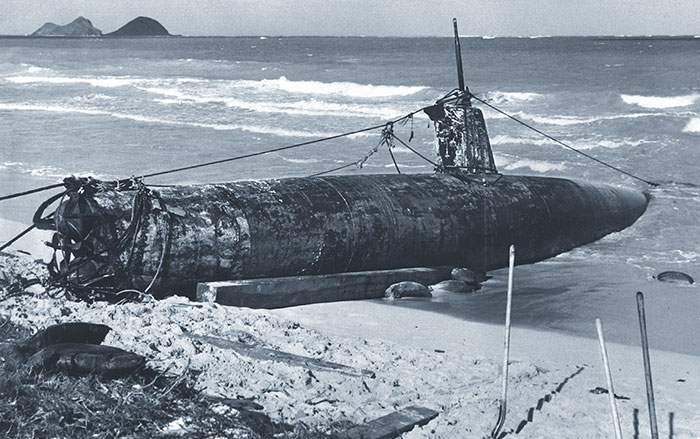

In 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management completed the first database of submerged cultural resources in the main Hawaiian Islands. Of 2,114 entries, just five come from the attack: two battleships in the harbor, two Japanese submarines in deep water, and a lone American seaplane. All were spared salvage—and in some cases discovery—for decades by some combination of depth, damage, and respect for the dead.

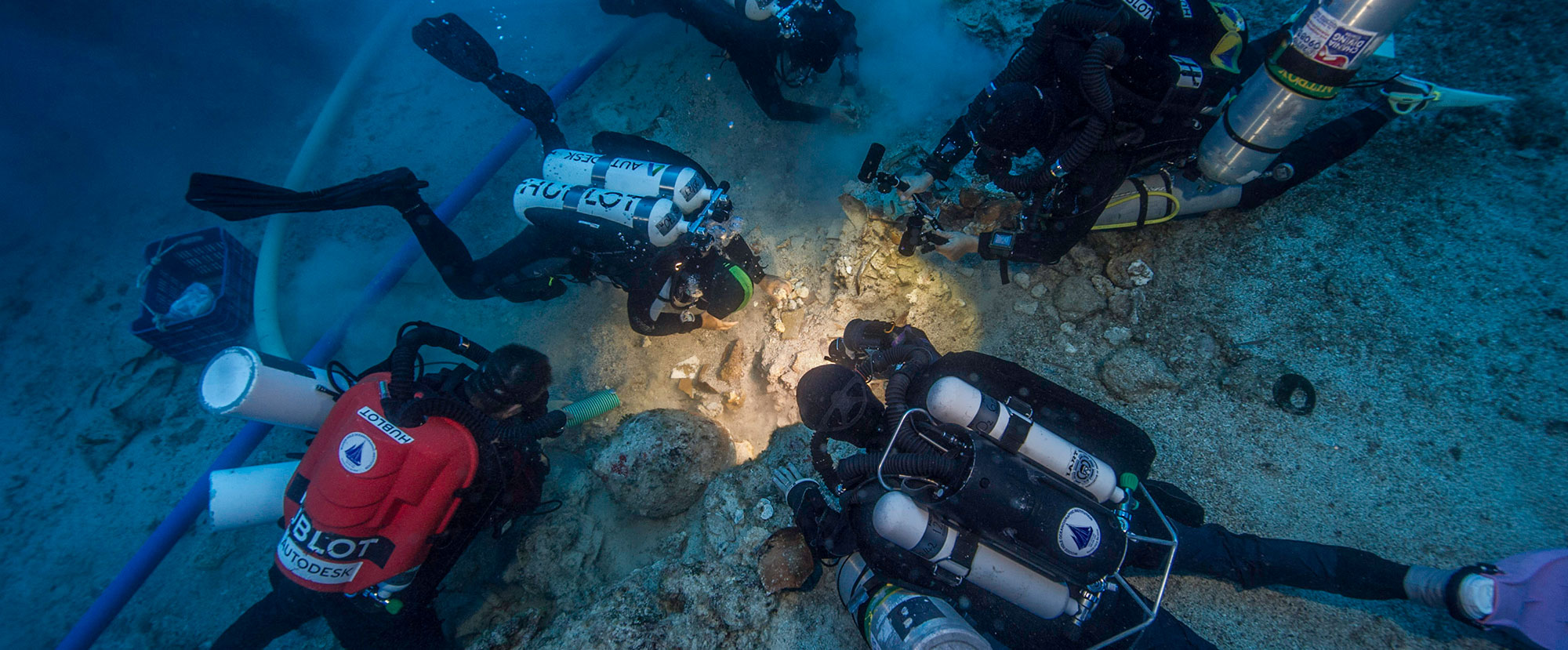

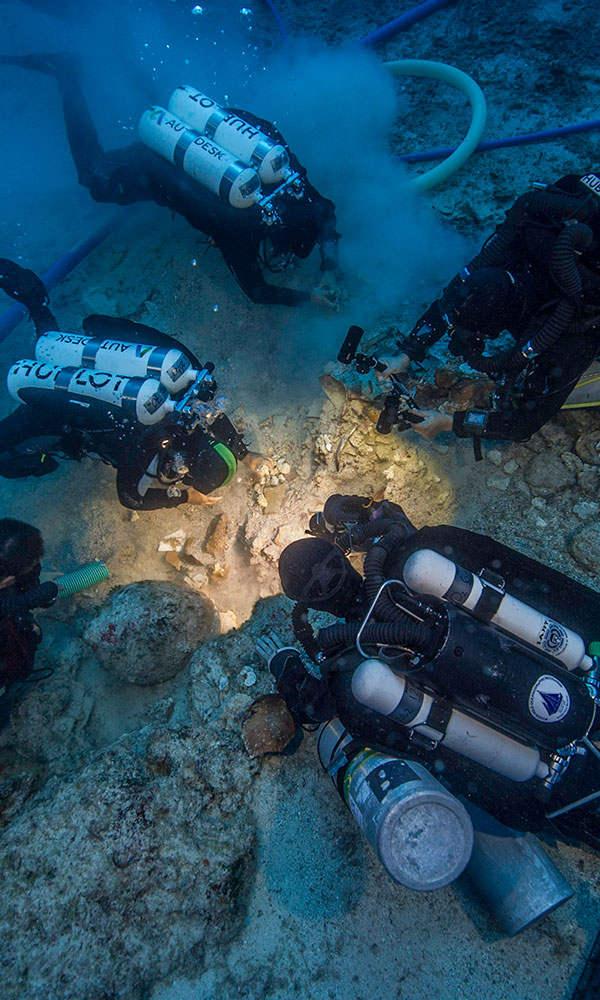

For the United States, Pearl Harbor stands alongside Yorktown, Gettysburg, Little Bighorn, and other iconic battlefields as a crucible of American identity. But it is different in both its freshness in memory and its inaccessibility, since most of the surviving remnants lie underwater, within active military installations, or both. It was 40 years before the underwater sites became the subject of archaeological inquiry. “We’re gaining a much more detailed understanding of the battlefield and all of its nuances,” says James Delgado, director of maritime heritage for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, who has been directly involved in several of the archaeological projects at Pearl Harbor. “Seventy-five years on, the view is far more comprehensive and three-dimensional, not just in terms of the major events, but also individual experiences.”

Today there are very few survivors of the attack, and fewer each year. The sites discussed here will soon be the only primary sources about an event that changed the course of the twentieth century. They are being studied not out of historical curiosity, but to ensure their stewardship for the future.

-

(U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

(U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command) -

(Official U.S. Navy Photograph, Naval History and Heritage Command)

(Official U.S. Navy Photograph, Naval History and Heritage Command) -

(Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives)

(Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives) -

December 7, 1941 January/February 2017

A Timeline of the Attack

(U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

(U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)