Within Norway’s Vestfold, along the western shores of the Oslofjord, a team of excavators burrows into the side of a large earthen mound. The barrow lies approximately 1,700 feet from the shore, protruding from a woodless plain. Armed with shovels, the diggers tunnel away with a determined resolve to reach the center. But these are not archaeologists—they are Viking raiders of the mid-tenth century. And they are seeking the stern of a subterranean ship, the final resting place of a bygone Viking ruler, known today as the Gokstad chieftain. As they vandalize the grave, they leave behind clues that, centuries later, will make their intentions clear and perhaps help identify the warrior whose tomb they have ransacked.

In January of 1880, word reached the Antiquarian Society in Oslo about an amateur archaeological dig occurring 75 miles to the south, outside the town of Sandefjord. Two brothers, sons of the owner of the large Gokstad farm, had begun treasure hunting on their father’s property. Their target was a 165-by-140-foot mound known locally as the Kongshaugen, meaning “King’s Hill,” as legend told of a famous king and his treasure buried there. Although damaged and reduced in size by centuries of plowing, the hill still stood a formidable 15 feet high. The following month, an emissary from the Antiquarian Society arrived. Archaeologist Nicolay Nicolaysen immediately suspended the unsanctioned digging as he assessed the situation. He soon determined that the site had great archaeological potential, and began a state-sponsored excavation later that spring. It took Nicolaysen’s team only two days to prove his suspicions correct when a boat’s wooden stempost emerged from the ground.

Despite the plundering more than a millenium before, the collection of artifacts buried within the Gokstad mound came to be one of the most extraordinary Viking archaeological discoveries ever made. In addition to the enormous wooden ship, which measures 76 by 17.5 feet and was adorned with 32 alternating black and yellow shields, three smaller vessels had been buried nearby. Inside a burial chamber behind the ship’s mast, a chieftain had been interred surrounded by an impressive assemblage of objects, including wooden furniture, riding, fishing, sailing, and cooking equipment, and a gaming board and horn gaming pieces, all intended to provide comfort and entertainment as he made the voyage into the afterlife.

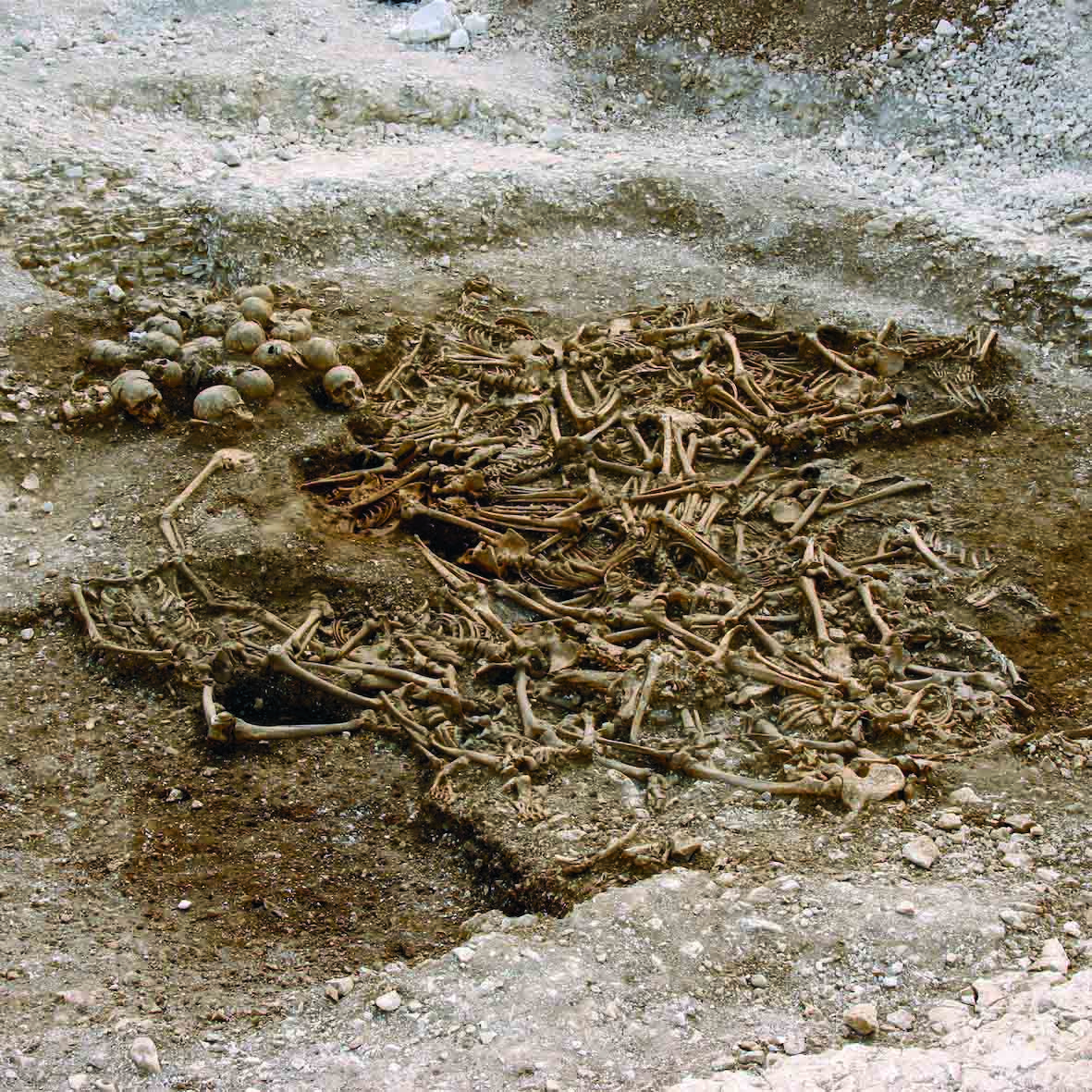

The archaeologists also discovered the remains of 12 horses, eight dogs, two goshawks, and two peacocks in the mound. However, the lack of any personal jewelry or weaponry was initially puzzling, as was the condition of the body itself. Only a handful of bones remained, and it eventually became clear that the skeleton had been purposely damaged.

Recent dendrochronological analysis has dated the Gokstad burial to between a.d. 895 and 905. The same analysis shows that the vessel itself predates the burial by as much as half a century, having certainly been used for trade, raiding, or exploration before it became the chieftain’s final resting place. Although not plentiful, evidence for the burial of large Viking ships has been found throughout northern Europe. Over the last 150 years, notable examples have been uncovered in Sweden, Denmark, and the British Isles, but the most remarkable and best preserved of these ships, including the Gokstad, have been discovered in southeastern Norway.

Given the extensive labor and resources required for the construction of such a ship, intentionally burying it would have been a tremendous testimonial to the deceased’s wealth and social position. The interment of Viking warriors within ships was partly a symbolic gesture, representing the soul’s journey into the afterlife. In addition, these burials were created by the dead chieftain’s descendants as physical reminders of the power and prestige of the recently departed. The Viking Age often saw contentious power struggles. Highly visible, extravagant burial mounds such as the Gokstad aimed to prolong the memory of a powerful chieftain, and to help ensure the transition of power to his heirs. Less than a century after its construction, though, the Gokstad mound was deliberately vandalized, possibly an attempt at desecrating this very memory.

During Nicolaysen’s excavation of the ship in the nineteenth century, the poor condition of the skeleton and the lack of valuable metal objects led archaeologists to conclude that the grave had been previously disturbed. In and of itself, this is not an unusual phenomenon in archaeology. Tombs are often discovered partially burglarized as a result of either ancient or modern treasure seekers. However, in the case of the Gokstad, researchers have recently confirmed that the reason for the break-in was more sinister than a simple desire for riches—it was personal.

To access the burial chamber, the ancient raiders dug extensive trenches measuring about 60 feet long, 15 feet deep, and several feet wide. This undertaking was too large to be a secretive mission obscured by the cover of darkness, but rather was a deliberate and highly visible act. Fortunately, the intruders left behind evidence of their conduct, in the form of a dozen wooden spades. Using new, nondestructive techniques of dendrochronological analysis, researchers from the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo dated these artifacts, potentially identifying the culprit(s). The evidence shows that the break-in of the Gokstad mound occurred between a.d. 950 and 1000. In conjunction with other dendrochronological data from sites including the Oseberg ship burial, which had been discovered in the early twentieth century some 15 miles away, archaeologists concluded that during the tenth century, a systematic campaign of “mound-breaking” was directed toward the monumental burials of eastern Norway. And that the man likely responsible was the Danish king Harald Bluetooth.

As the Dane sought to extend his power over the region in the second half of the tenth century, he aimed to undermine the authority of the local ruling dynasties. Because burial mounds such as the Gokstad represented the legacy and authority of these dynasties, both symbolically and physically, they were purposely and systematically wrecked. By destroying the previous ruler’s remains, memory of him could be destroyed. The Gokstad chieftain’s skeleton was intentionally dismembered, his valuables plundered, and the symbolic transition of power was complete.

Early examinations of the Gokstad chieftain never arrived at definitive proof of who he was, what he looked like, or how he died. When Nicolaysen discovered the body in 1880, he found only a handful of broken bones from the original skeleton, including pieces of four leg bones, a shoulder blade, a fragment of an upper arm bone, and two skull fragments. As early as 1882, anatomist Jacob Heiberg concluded that the individual was between 50 and 70 years old, suffered from muscular rheumatism, and had difficulty walking. This led to the general consensus at the time that the bones belonged to a local Viking king, Olav Geirstadalv, who historical sources record as dying around a.d. 840 from a foot infection. In 1928, the skeleton was sealed inside a lead coffin and reburied in the Gokstad mound. The stone sarcophagus containing the casket bore the inscription, “In this coffin Olav Geirstadalv’s bones were placed anew.”

The skeleton remained interred in the reconstructed mound on the original site until 2007, when Per Holck, professor emeritus from the Department of Anatomy at the University of Oslo, led a team of scientists urging that the remains be exhumed. Holck was particularly worried that the lead coffin in which the bones had been sealed may have trapped damaging moisture. “I expressed my concern about the skeleton, as the moist conditions could have destroyed it completely. I also pointed out that the former examinations had not mentioned several sorts of pathology at all, and no X-rays had been taken,” says Holck.

The exhumation allowed for a modern forensic investigation of the Gokstad remains and provided results that contrasted with the earlier conclusions. Most importantly, the new examination offered clues as to what the Gokstad chieftain may have looked like and how he died. One of the first things that Holck noticed was the man’s abnormally large stature. Using the surviving long bones as a guide, he estimated that the Gokstad chieftain was nearly six feet tall, almost half a foot taller than the average ninth-century Viking. The lack of wear on his joints indicated that he was probably in his 40s when he died, younger than previously thought. Although most of the chieftain’s skull was missing, making it impossible to reconstruct his facial features, Holck’s close examination of an X-ray of one of the skull fragments has provided some details of the man’s physical characteristics. For example, the base of his skull, where the pituitary gland is located, showed damage, likely resulting from a tumor. “The abnormal massiveness of his skeleton was in accordance with acromegaly, a syndrome which appears due to a hypophyseal [pituitary gland] tumor in adult age,” says Holck. “He would have had a big and coarse-limbed body, enlarged nose, ears, and lips, big and sweaty hands and feet, and a deep and toneless voice.”

The Gokstad chieftain likely suffered other painful side effects of this disease, including difficulty moving the vertebral column, relatively weak muscular strength, limited motor skills, and frequent migraines. “These symptoms, especially the constant headaches, may have made him ill-tempered,” says Holck, “which certainly was a bad situation at that time!” Holck also noted that the chieftain must have had difficulty walking, a circumstance that had led earlier investigators to associate the Gokstad skeleton with Olav Geirstadalv. Examination of his knee joint indicated that, at one point, the chieftain had suffered severe ligament damage and fractures of the left leg, likely from a bad fall. This may have caused him to limp, although the injury had occurred several years before his death and was partially healed when he died.

Somehow the chieftain’s true cause of death had been missed. Says Holck, “The former examination of the skeleton did not comment on the chieftain’s [fatal] injuries.” In his recent study, Holck was able to better detail extensive wounds that were almost certainly received in battle, and to identify the injuries that the Gokstad chieftain could not have survived. The results tell a more vicious story than had been previously written. “He certainly did suffer a violent death,” Holck says. The man had been severely slashed in both legs, likely by two individuals using different types of weapons. A distinct cut from a thin-bladed weapon, such as a sword, was evident along his left shinbone. This would have sliced through the patellar tendon, rendering his left leg useless. The direction of the mark indicated that the chieftain was likely already lying on his back when this occurred, perhaps with his legs in the air. Although severe, this probably was not the fatal blow. “A second kind of weapon, probably a knife, gave him a deep cut mark on the inside of his right thigh bone. This may have penetrated the femoral artery and perhaps caused his death,” explains Holck. “These blow marks on his lower limbs did not show any new formation of bone, and thus indicated that he was killed in battle.”

Although scholars cannot yet connect the burial with any particular historical figure, and attempts to retrieve DNA have been unsuccessful thus far, they now know that it is certainly not Olav Geirstadalv. Nonetheless, the Gokstad chieftain and the circumstances of his burial are representative of a singular moment in Viking history—one defined by power, exploration, and wealth, thanks in large part to advances in shipbuilding technology. Extraordinary ship burials like the Gokstad were important symbolic landscape markers, but even they were unable to avoid the repercussions of local power struggles and territorial disputes.