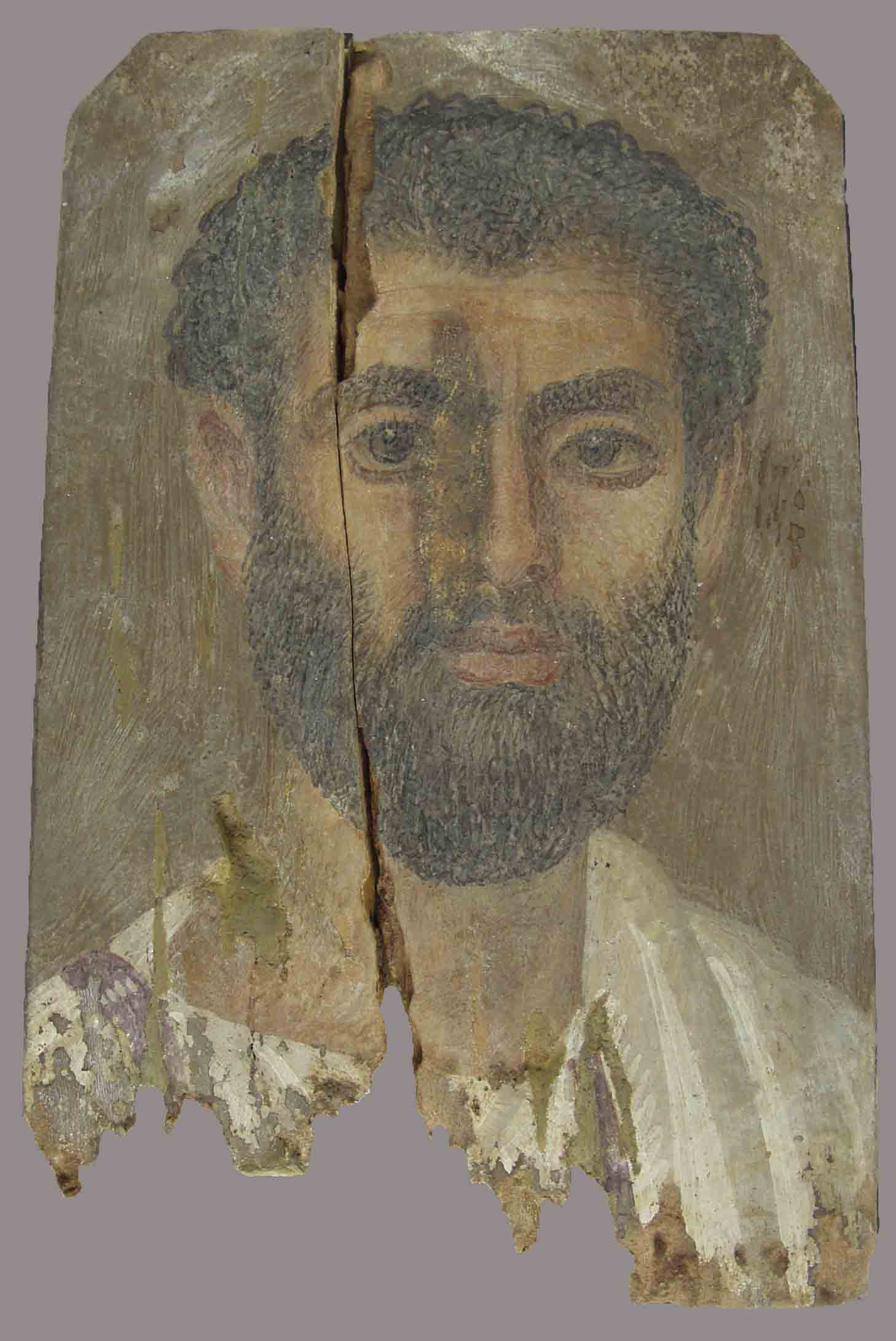

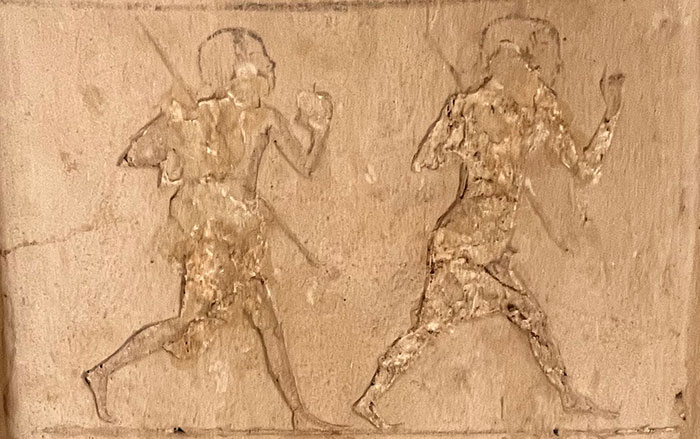

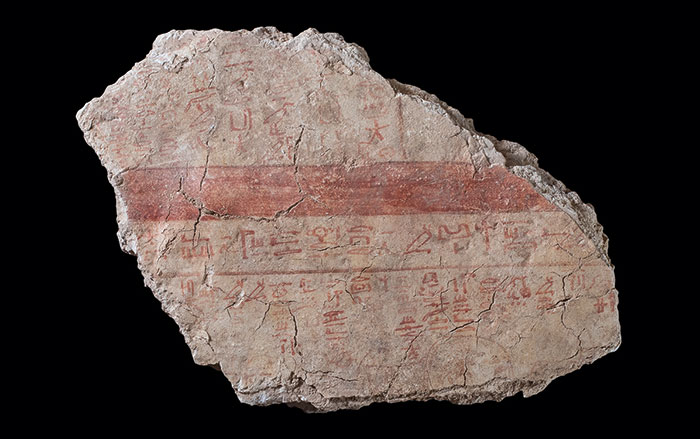

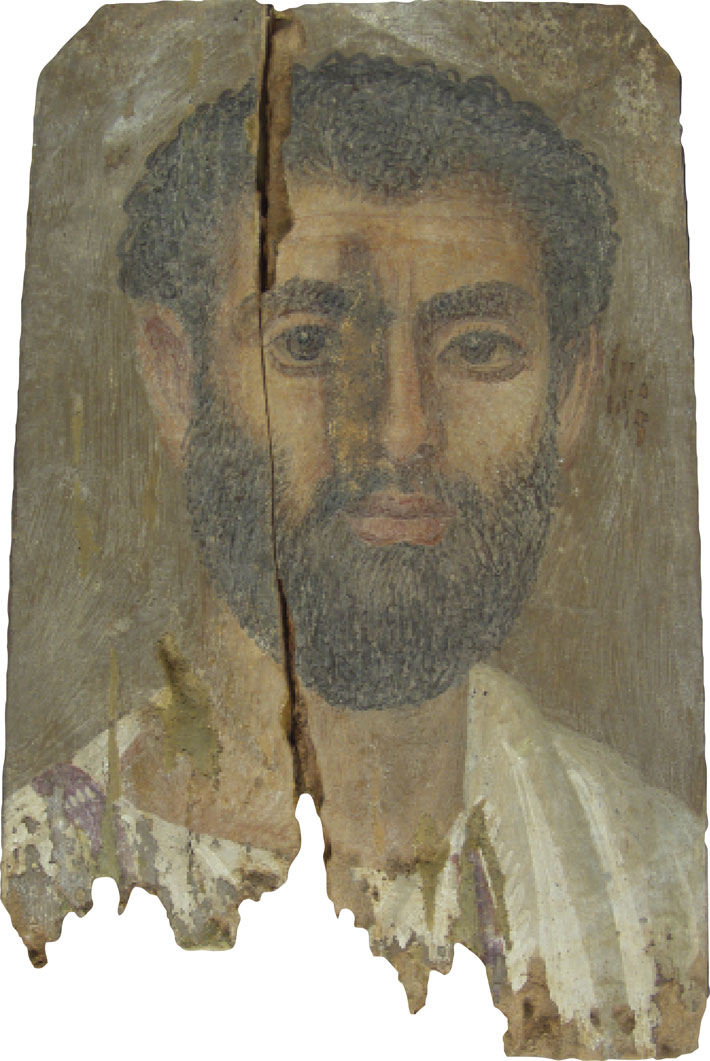

Researchers unexpectedly found evidence of Egyptian blue, the earliest known artificial pigment, in sections of paintings from Egypt’s Roman era that lack even a hint of visible blue coloring. These areas include swaths of gray background, a white tunic and mantle, and an under-drawing outlining a face. The paintings are part of a collection of mummy portraits and panel fragments housed at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, and are thought to date to the second century A.D.

Using an array of technologies, including near-infrared luminescence and X-ray diffraction, the researchers were able to detect Egyptian blue, technically known as calcium copper tetrasilicate. The pigment may have been used to subtly modulate colors or add a shiny quality. It is also possible that Egyptian blue, used at least as early as 3100 B.C., was no longer a scarce commodity by the Roman era. “We have perceived it as a pigment that was rare and expensive,” says Jane Williams, a conservator at the Hearst Museum, “but maybe it wasn’t. Maybe it was just part of what was available in the mix.”