Any visitor today to the site of Los Adaes, in northwest Louisiana, will take in a landscape that was the easternmost point of Spanish expansion in the southwest. It was the location of a Spanish mission and presidio, constructed in 1721 and occupied until 1773, in a high, defensible position. A previous Los Adaes mission had been built in 1717, a short distance away, but was abandoned because of initially poor relations with the Caddo Indians. According to archaeologist George Avery of Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas, the Los Adaes mission, and others like it, was regarded as a less expensive alternative to military occupation. The Spaniards’ intention was to halt French incursions into the region and to prevent the French from using the Mississippi River as a means to trade with Mexico. They also were supposed to convert the Caddo to Catholicism. The Los Adaes mission, however, situated on the frontier and far from both Spain and Mexico, took on a unique character. According to archaeologist Pete Gregory of Northwestern State University, Los Adaes became a place of intense cultural exchange among the Spanish, the French, and the Caddo. “It’s what we call ‘creolization’ here in Louisiana,” he says. The archaeological record, with its robust mixture of ceramics from all three cultures, bears this out. Ultimately, these people weren’t supposed to get along, “but,” says Gregory, “they did.”

THE SITE

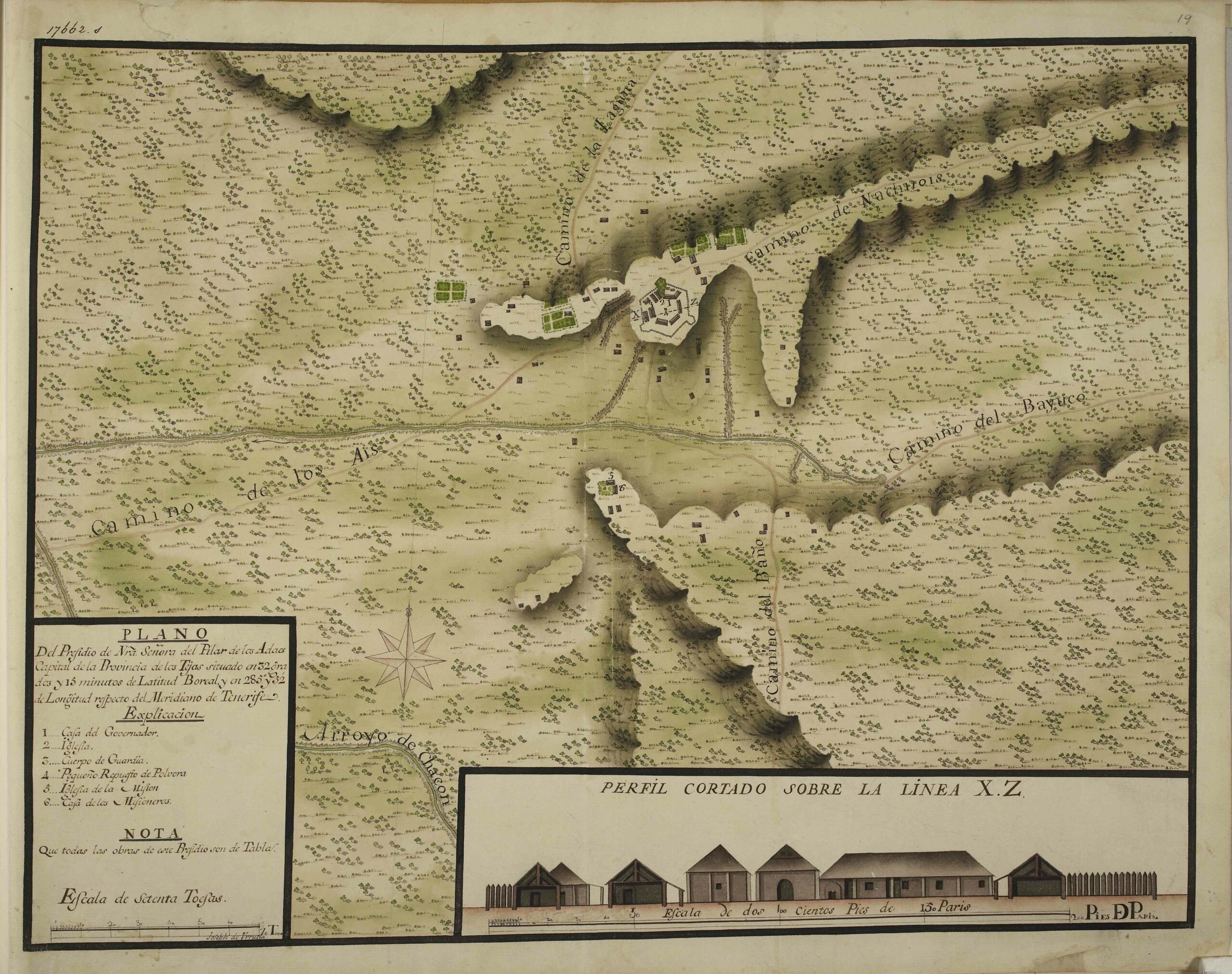

Los Adaes remained largely undisturbed from the time it was abandoned in 1773 until Gregory conducted archaeological investigations at the presidio in 1962. His initial aim was to confirm that the site was indeed Los Adaes. He uncovered a large quantity of French and Spanish ceramics, with the latter having been made in Pueblo, Mexico. Asian porcelain, which had arrived by way of Acapulco, was also discovered and reflected the robust trade route that reached from Mexico all the way to Los Adaes. More than 70 percent of all ceramics found across the site are Caddo in origin. The mission itself sits partially on private land and has not been excavated. In 2014, geophysical survey of the mission site was conducted. While only a small percentage of Los Adaes has been excavated, a 1767 map by cartographer Joseph de Urrutia, once thought to have been created for planning purposes, has been discovered by archeologists to be a reliable rendering of the settlement.

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

The visitor center is open on Wednesday through Saturday, noon to four, and is a favorite field trip for Texas schoolchildren, since Los Adaes was the colonial capital of Texas. Replicas of many of the excavated artifacts of colonial frontier life are on display, including French, Spanish, and Caddo ceramics, along with a detailed timeline of Los Adaes history. In addition, tour guides are available and walking trails with markers wind throughout the site.