On a spring afternoon in 2017, archaeologist Jan Simek led a group of graduate students into the dark, wet mouth of a Tennessee cave. They slipped past cave crickets and ducked under a colony of bats clinging to the ceiling. When they came to the end of the passage, the group belly-crawled through a crack in a wall and emerged in a small chamber. Simek angled his headlamp over the chamber’s walls to reveal hundreds of strange images carved into the stone: a serpent with antlers, a mud wasp with delicate wings, an entire flock of birds that seemed to soar across the wall. The images had been engraved by Native Americans 1,200 years earlier, during what archaeologists call the Woodland period (1000 B.C.–A.D. 1100), when hunter-gatherers were beginning to settle into an agricultural lifestyle. When the group eventually retreated toward the exit, one of Simek’s students, a tall, quiet man named Beau Duke Carroll, lingered in the chamber. He was staring at a small carved figure of a man with wings and a sharp beak. Carroll is Cherokee, a member of the Eastern Band born and raised on Cherokee-owned territory in North Carolina. His ancestors once called this part of Tennessee home. Carroll pulled from his pocket a pouch of tobacco that had been consecrated by Cherokee elders and sprinkled it over the cave floor, then he turned and crawled back out.

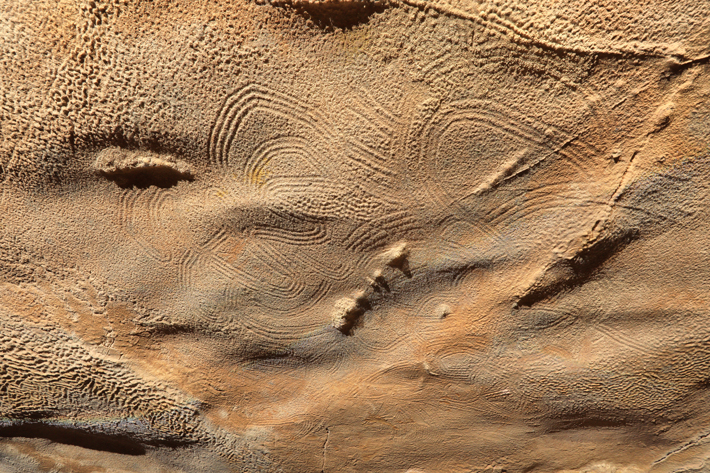

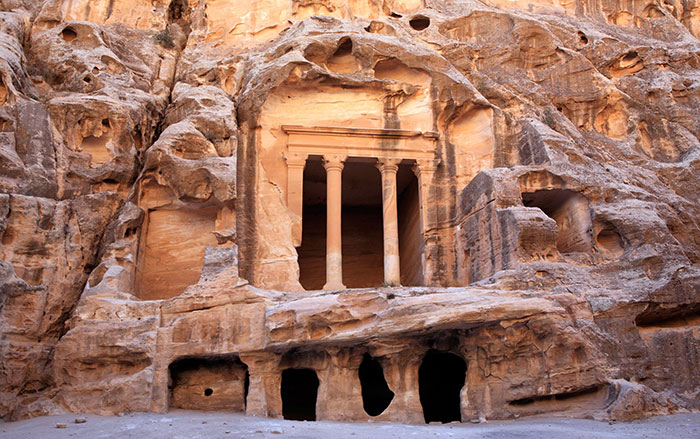

Twelfth Unnamed Cave, as this cave is known, is one of more than 100 caves in the woodlands of Tennessee, Alabama, and Kentucky where, in recent years, archaeologists have uncovered a vast trove of prehistoric art. The Unnamed Caves—so-called to obscure their locations from looters—contain extraordinary images of humans, animals, celestial beings, and phantasmagorical creatures. They take the form of carved petroglyphs, charcoal pictographs, and mud glyphs traced into soft walls. The oldest artworks go back more than 6,000 years, but most were made during the Mississippian period, between A.D. 1000 and 1600. Like the renowned Paleolithic cave paintings of Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain, the artworks in the Unnamed Caves appear in what archaeologists call the “dark zone,” the deepest stretches of a cave, beyond the reach of natural light. The ancient artists reached these chambers by squeezing down long passageways and climbing on ropes or wooden scaffolding, all by the faint light of torches made of river cane. Simek and his team have spent years documenting the Unnamed Caves, recording and mapping each image, trying to comprehend what drove the artists so deep into the dark. To find answers, Simek has recently joined forces with Cherokee scholars such as Carroll, who are combining scientific archaeological practices with deep-rooted traditional tribal knowledge. Together, they are bringing life to the ancient artworks in ways no one had thought possible.

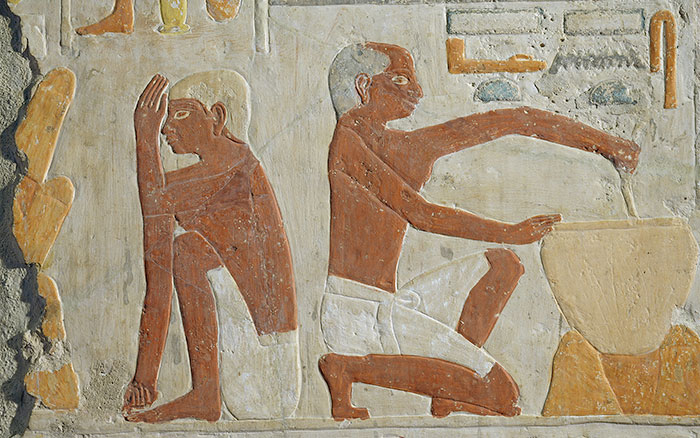

The first dark-zone art in the Southeast was discovered in 1979, when two local cavers shimmied down a cave passage in Tennessee and noticed an image of a bird incised into a mud wall. One of the cavers happened to have studied Native American archaeology and recognized the imagery from statues, bowls, and weapons excavated from burials at Mississippian mound cities such as Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis. The iconography was typical of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, the term given to a common set of religious practices and symbols that spread through the Southeast during the late Mississippian period. For rock art researchers in North America, the cave, dubbed Mud Glyph Cave, was a revelation. They had seen many examples of Native American rock art painted on cliff faces and carved into the walls of canyons, but never in the pitch-dark depths of caves.

When Simek arrived at the University of Tennessee in 1984, he was intrigued by the findings at Mud Glyph Cave. He had begun his career excavating caves in Europe and cherished his visits to Lascaux and Altamira, peering in the dark at 17,000-year-old images of reindeer, horses, and bison galloping across the ceiling. “I’d look up at those paintings and just tremble,” he recalls. He wondered what secrets the limestone hills of Tennessee might hold.

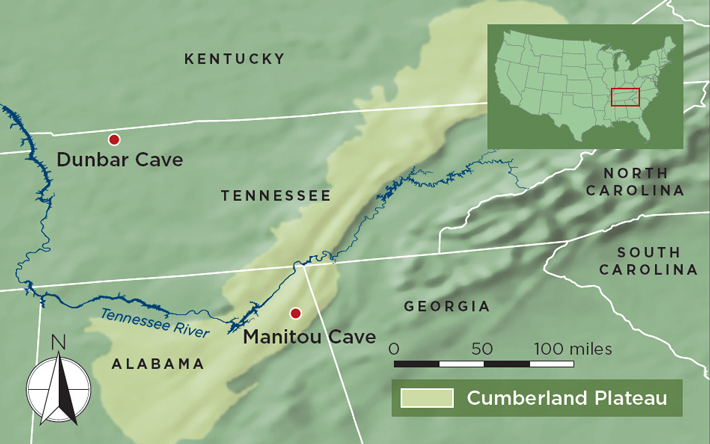

Simek focused his search on the landscapes stretching beyond Mud Glyph Cave, including the Tennessee River Valley and the Cumberland Plateau, both of which are honeycombed with caves. He spent long summer days bushwhacking through the forest in scorching heat, dodging timber rattlers and slapping at chiggers as he searched for caves. As a newcomer to Tennessee, Simek was still learning to read the landscape, so he recruited a team of local cavers and amateur historians, people who knew the land intimately. It was not long before they began to find caves containing traces of prehistoric visitors—charcoal streaks from cane torches, ancient footprints, and images engraved on the walls. “Once we knew what to look for, we began finding art everywhere,” Simek says. He saw engravings of owls and a type of fish called gar, reliefs of turtles, and even portrayals of men playing stickball, a ceremonial game played by Mississippian peoples. Each year, Simek and his crew discovered more new sites and added to the catalog of Unnamed Caves.

In Europe, early twentieth-century archaeologists had developed a theory that the artworks at Lascaux and other caves were the visible remnants of prehistoric religious practices. Simek saw hints that the Unnamed Caves had also, perhaps, been the sites of religious rituals. In Eleventh Unnamed Cave, for example, he discovered the ceiling was studded with more than 100 fist-sized gobs of mud that contained half-burned stalks of river cane. The ancient Native American artists, it seemed, had set the cave’s interior ablaze with prehistoric sparklers. Sometimes Simek would slip into a chamber and find ash fallen from torches thousands of years ago preserved in the cool mud.

As Simek and his team explored more and more caves and recorded the iconography and location of each image, they began to detect patterns. Images carved closer to the cave entrance tended to be clearer, more realistic representations—humans holding bows, for example—while the deep, hard-to-reach galleries contained images that were more enigmatic, such as men with bird wings and panthers with eagle talons. “They seemed to be moving from mundane to transcendent,” Simek says, “from visible world to underworld.”

From time to time, Simek found himself staring at a cave wall that had been deliberately scratched in an almost frantic manner, without any attempt to create a figure. It seemed that interacting with the walls was, in itself, a significant activity. Sometimes he came across images of human faces drawn on walls alongside large hands, as though the artist were portraying a person pressing against the wall from within. To Simek, the images looked like beings who lived beyond the rock wall reaching out to the viewer. He imagined that the ancient artists treated the cave walls as a veil between the earthly world and the supernatural world beyond.

Simek knew that all of this was conjecture. Like the cave paintings in Europe, the artworks in the southeastern woodlands were created well before the beginning of recorded history. “With prehistoric art, we’re always speculating,” says Simek. But, unlike the paintings in Lascaux and Altamira, where all direct knowledge of the artists has been lost to history, the images he was finding in Tennessee had been made by people whose descendants were known and who, in some cases, still lived near the caves. Simek wondered if the caves might still hold a place in the memory of Native Americans—but he didn’t know how to test this notion.

Then, in 2015, Carroll enrolled in the master’s program in archaeology at the University of Tennessee, where Simek was the head of the department. When it came time to write his thesis, Carroll turned to a site in northern Alabama called Manitou Cave. There local cavers had made a startling discovery almost a decade before.

The mouth of Manitou Cave opens on the side of Lookout Mountain, above the town of Fort Payne, which, during the nineteenth century, was the site of a thriving Cherokee community called Willstown. On a recent morning, Carroll and Simek hiked a mossy trail up the mountain. Carroll, now a Cherokee tribal historic preservation officer, led the way. Together they slipped into the mouth of the cave, where they were engulfed by a heavy, wet darkness.

The Cherokee relationship with caves is intimate—the name Cherokee is said to mean “People of Cave Country”—but fraught. From boyhood, Carroll had been taught by elders that even the smallest step into the mouth of a cave was the beginning of a spiritually potent and potentially dangerous endeavor. “Everything in a cave is the opposite of the surface world,” says Carroll. “It’s dark, it’s chaotic. Things are unpredictable.”

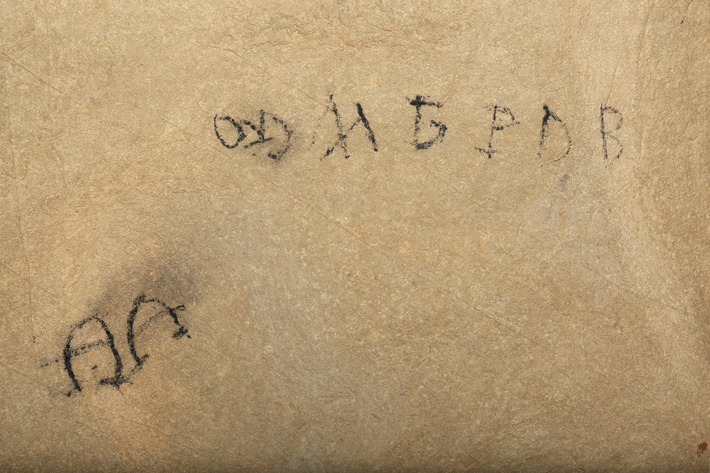

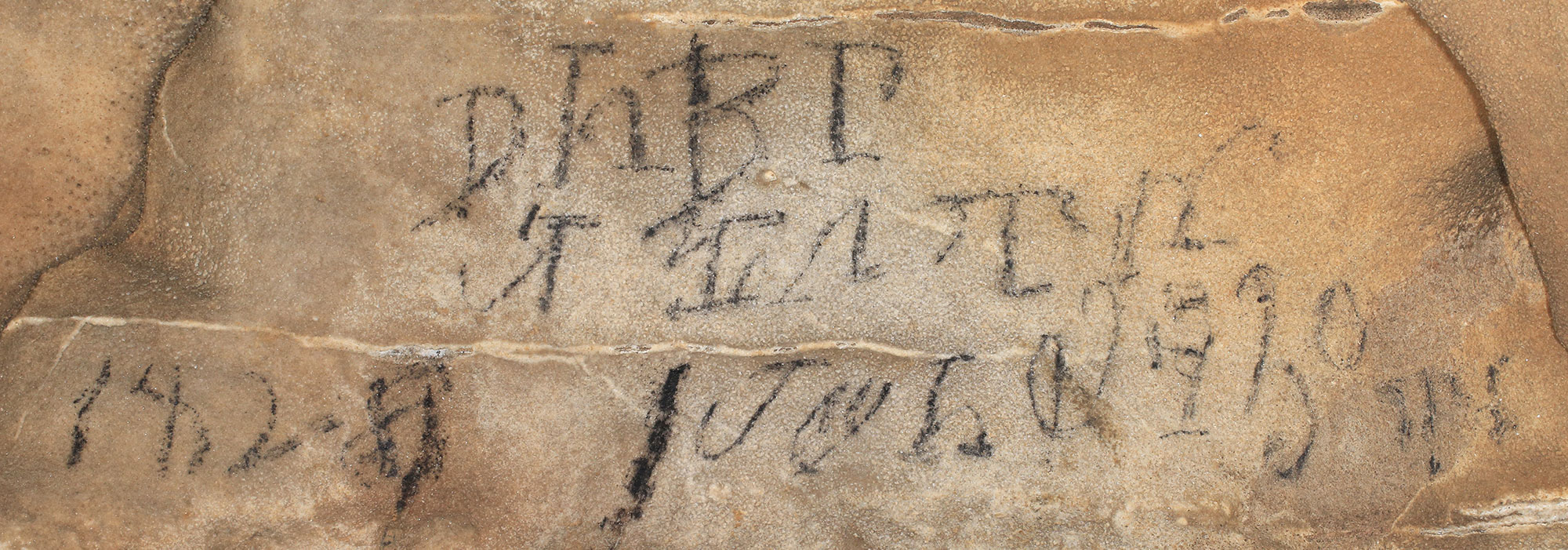

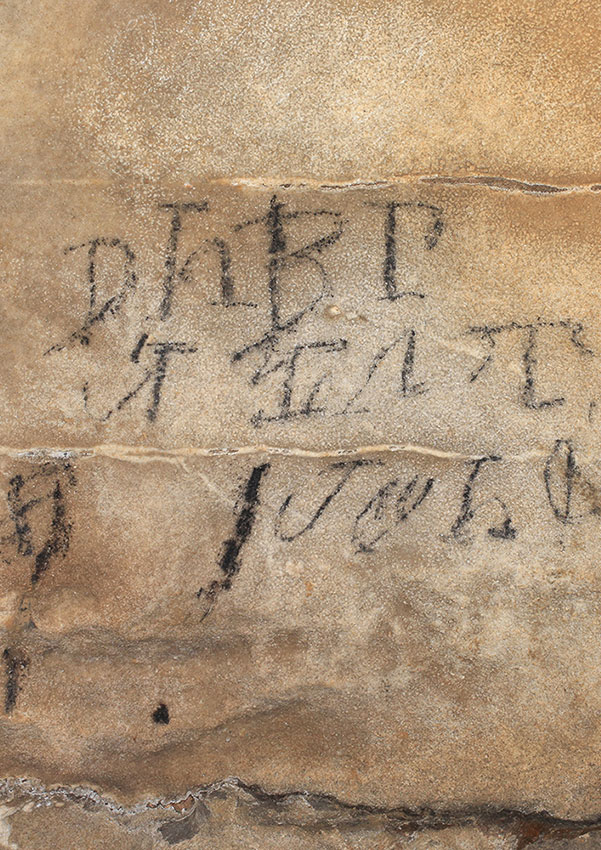

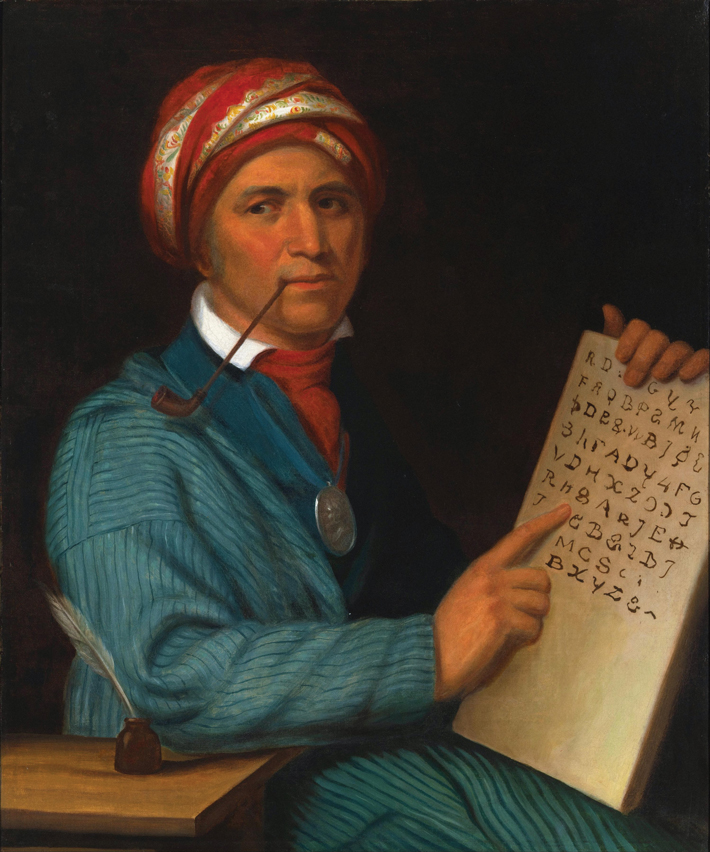

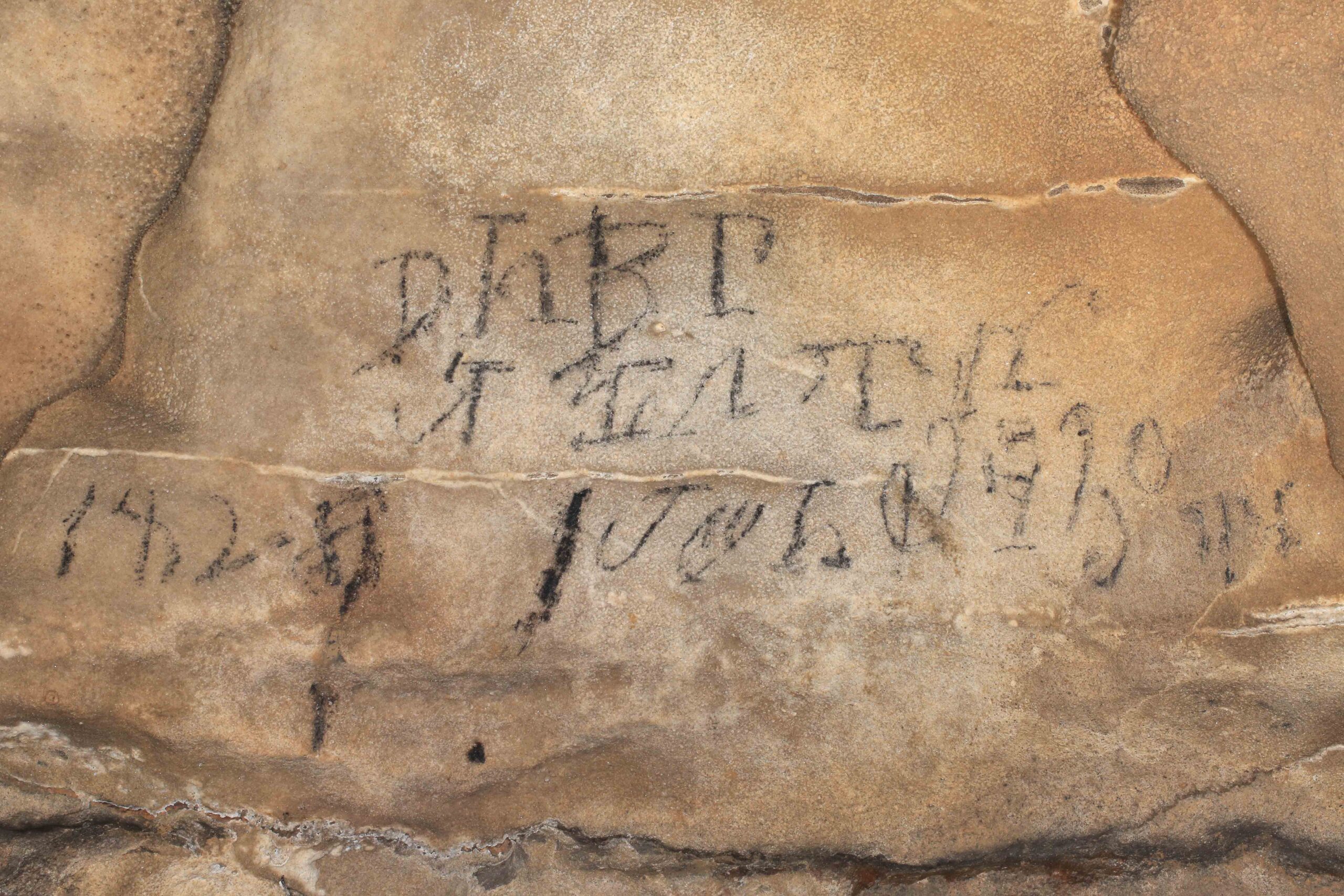

For much of the last two centuries, Manitou, which is privately owned, has been a tourist attraction renowned for its towering stalagmites and soaring chambers in which the cave’s late nineteenth-century owners would host candlelit dances. Close to the entrance, the cave walls are covered with graffiti. As Carroll and Simek moved deeper into the cave, they passed layers of looping signatures dating to the late nineteenth century alongside more recent exclamations of “Roll Tide,” the University of Alabama’s rallying cry, left by local teenagers. Eventually they clambered beyond the tourist route, following the path of a burbling stream until they reached the last chamber, some three quarters of a mile from the entrance. Carroll illuminated one wall, revealing a curious tableau of engraved text. At first glance, it resembled the Latin alphabet, but a closer look revealed unexpected flourishes and serifs. In fact, the characters were part of the Cherokee syllabary, a writing system whose characters represent syllables rather than vowels and consonants. It was developed in the early nineteenth century by the renowned Cherokee scholar Sequoyah—also known as George Guess—as the written expression of the spoken Cherokee language. Sequoyah’s syllabary was a landmark achievement, the first time in recorded history an individual indigenous person had developed a writing system for a strictly oral language. While the precise details surrounding the development of the syllabary are elusive, historians do know that Sequoyah and his family lived in Willstown.

Simek had been aware of the inscriptions since 2006, when they were first spotted by local cavers, but no one knew what they meant until Carroll undertook to translate them. Carroll had learned to read Cherokee in school, but because the language varies from region to region and has evolved over generations, portions of the text escaped him. He spent months working with Cherokee historians and tribal elders, showing them images of the text and gradually piecing together their interpretations. When Carroll finally presented his findings, Simek was stunned. The inscriptions described, in rich detail, a religious ritual performed in the cave nearly two centuries earlier.

Deeper inside the cave, Carroll cast his lamp beam over one stretch of neatly painted script and read aloud: “on the thirtieth day of their month April 1828.” It was the date on which the ritual’s participants visited the cave. “Their” referred to the calendar of the encroaching white settlers. Carroll continued reading with only the light from his lamp penetrating the dark, pointing out where the visitors identified themselves as “the leaders of the stickball team.” The ball game is still played by Cherokee people today—Carroll himself had grown up playing it. Much like lacrosse, stickball is played by two teams using sticks with baskets attached to move a ball through goals at either end of a large field. But it is more than just a game—it is a symbolic reinforcement of the Cherokee cosmos, an homage to past warriors, and a training ground for future warriors. The Cherokee call stickball “the little brother of war.” A single contest could last multiple days and would be punctuated with religious ceremonies in which a medicine man led the players to a secluded place to perform rituals. During these ceremonial intermissions, which Carroll knew from ethnographic literature as well as from personal experience, the ballplayers danced, prayed, bathed in smoke, and cleansed themselves in sacred spring water. The inscriptions in the cave made reference to some of these very rituals. Carroll guided Simek to an inscription engraved in the wall next to where the cave’s stream bubbled up from the earth. “We call it ‘going to water,’” said Carroll. He was quiet for a moment, as he and Simek listened to the echo of the stream in the dark. “Where water comes out of the ground, you could say it’s like a portal to the spirit world.”

Many of the inscriptions in Manitou Cave startled Cherokee elders because they were so sacred, referencing religious practices that Carroll could not speak about publicly. On one wall, Carroll found the signature of the medicine man who led the rituals—“the man of authority,” as he calls himself in the inscription. The medicine man was Richard Guess, the son of Sequoyah. At the time of Guess’ visit with the stickball team, the Cherokee were facing a cataclysmic upheaval. Just two short years later, President Andrew Jackson would sign the Indian Removal Act. This law required the Cherokee to leave their homeland and migrate to territory that later became Oklahoma on the journey known as the Trail of Tears. A number of Cherokee, though, took refuge in the mountains of North Carolina, eventually becoming the Eastern Band. Carroll suspects that Guess and the Cherokee ballplayers, with the threat of removal looming, traveled so deep into the cave and took such great pains to record their visit in order to leave a record of their practices for future generations. “They wrote this to be preserved over time,” he says.

Before exiting the cave, Carroll and Simek paused in a high-ceilinged hall where, high above the tourist graffiti, is an inscription. It reads ᎠᏴᏏᎵᏔᏍ, or a-yv-si-li-ta-s, Cherokee for “I am your grandson.”

“They’re addressing the Old Ones,” says Carroll. Then he explained something curious: The inscription was actually written backward, the symbols moving from right to left.

“They didn’t write it to be read from down here,” he said, gesturing to the cave floor. The intended readers, it seemed, were the spirits of ancestors on the other side of the stone.

Archaeologists have long used oral history and ethnography to help them understand the past. But Carroll’s findings have opened an entirely unprecedented line of inquiry, in which indigenous practitioners of a ritual have left written accounts of their own ritual practices, in their own words. “They are telling us that this was a ritual space,” says Simek. “It’s not speculation. We know.” Carroll recognizes that he cannot necessarily apply contemporary Cherokee beliefs to the imagery in the Unnamed Caves. Yet he also knows that many of his tribe’s traditions are rooted in the stories and beliefs of older, ancestral tribes who inhabited this landscape long before the Cherokee. On occasion, when Carroll visits an Unnamed Cave with Simek, he finds imagery he recognizes from tales his grandparents told him. Many Cherokee stories, for example, revolve around characters known as the Thunderers, celestial beings known for their ability to transform from human to animal—man to hawk, man to bear. During that first visit with Simek to the hidden chamber of Twelfth Unnamed Cave, when Carroll saw the engraving of the man with wings and a beak, he had thought of the Thunderers.

Recently, Simek and Carroll traveled together to Dunbar Cave, an eight-mile-long cavern in middle Tennessee that lies on one branch of the Trail of Tears. At the end of a winding passage, they came to an expansive hall. When they reached the back wall, they crouched together before a charcoal painting made during the Mississippian period, around a.d. 1300. It was of a man, stretching seven feet long. Instead of feet, he had large animal paws with sharp claws—he was changing shape, transforming from human to animal. Were they looking at an ancestral expression of a Cherokee Thunderer from 700 years ago? Perhaps. They can never know for certain.

Shortly after their visit to Dunbar Cave, Simek and Carroll learned that a park manager had found an inscription in the Cherokee syllabary etched into a wall not far from the shape-shifting figure. Carroll is not yet sure what the characters say, but he understands their significance. In the early 1800s, as his ancestors walked the Trail of Tears, they paused to visit this cave and leave their mark in a place that had long inspired reverence—a place where their ancestors had found both communion and solace since the earliest days.

Slideshow: Artworks of the Dark Zone

Since the 1980s, archaeologist Jan Simek and his colleagues have surveyed prehistoric artwork decorating the deepest reaches of caves, including the so-called “Unnamed Caves,” of Tennessee and Alabama. Many of the artworks were incised on the mud walls of these caves. In recent years, Simek and Beau Carroll, lead archaeologist of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Tribal Historic Preservation Office, have also studied inscriptions Cherokee left behind in the caves using their own writing system. Below are images of some of these artworks and an inscription taken by photographer Alan Cressler. (All images are courtesy of Alan Cressler. To see more, go to Cressler’s Flickr.com site.)