The time: 1955. The place: a dry lakebed in southern Nevada called Frenchman Flat. An explosion equivalent to 22,000 tons of TNT creates a roiling mass of superheated, low-density gas. This fireball rises and collides with the surrounding air, creating turbulent vortices that suck smoke and debris up from the ground into a column. The “stem” rises into cooler, thinner air, where the ascent slows, debris disperses, and moisture condenses to form a “cap.” Over days and even months, nuclear fallout spreads and drifts to Earth.

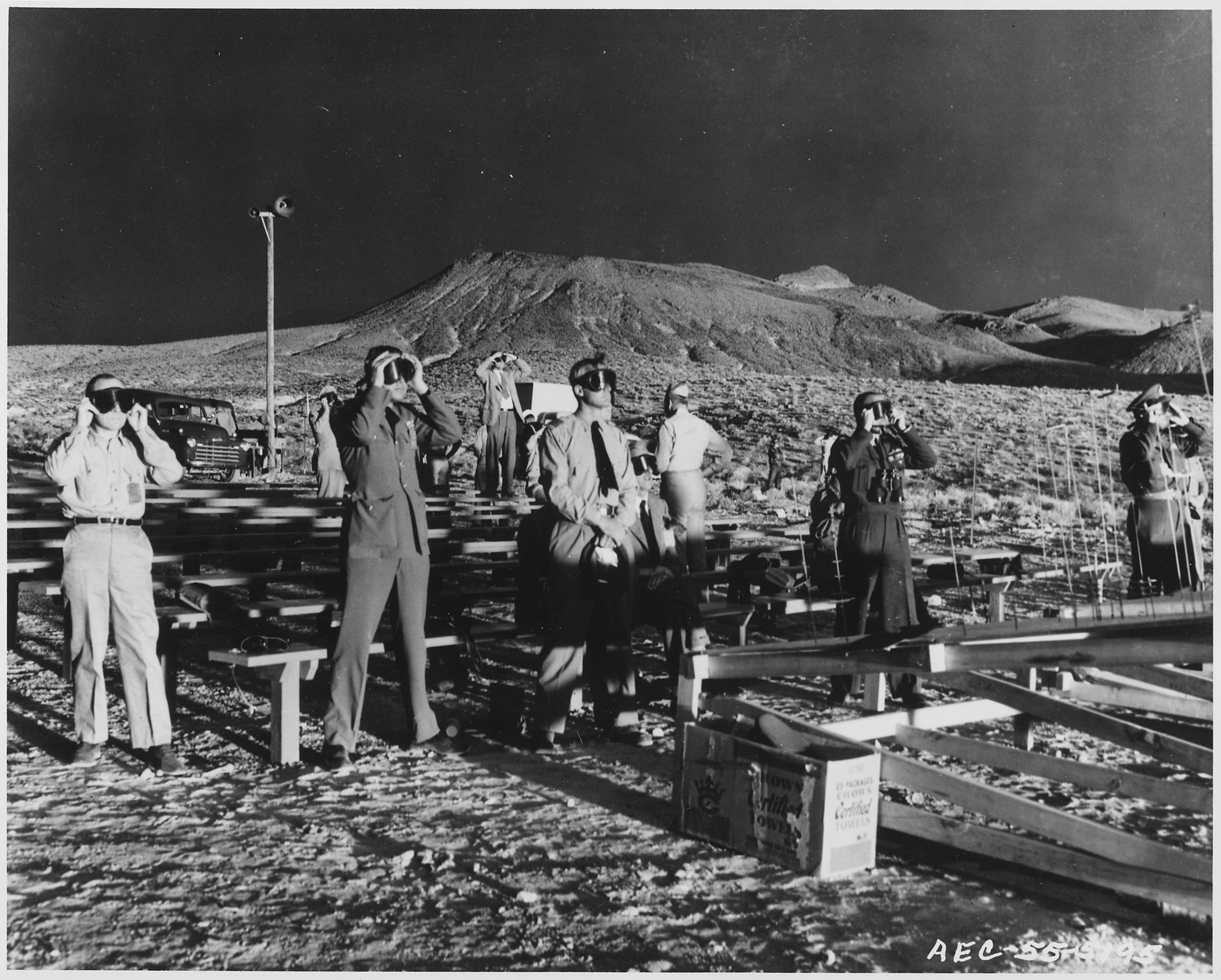

Between 1951 and 1962, well after the detonations at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 14 mushroom clouds rose above this corner of the Nevada desert. They were part of a long, complex, and varied program of nuclear testing, and each had a broad audience. One part was global, as the Cold War superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, squared off; the other was sitting on benches on an overlook seven miles away. A stream of political and military VIPs sat there, squinting at blasts and being buffeted by powerful shockwaves. Today, 11 rows of the benches sit under the desert sun, with nails jutting from their warped, desiccated planks. “I like these benches,” says Colleen Beck, an archaeologist with the Desert Research Institute (DRI), part of the Nevada System of Higher Education. “While hardly anyone comes here now, you can really imagine people sitting on them, watching a test.”

Frenchman Flat is one of 14 historic districts at what was once called the Nevada Test Site (now the Nevada National Security Site), 1,360 square miles of dust, scrub, and mesa managed by the U.S. Department of Energy. This battlefield that never saw a battle was a main source of the heat of the Cold War. All told, more than 1,000 nuclear weapons were detonated at the Test Site—aboveground and in tunnels—over more than 40 years. Material from these experiments is scattered across the landscape. Each squat building, twisted hunk of metal, and heavily gated tunnel entrance reflects the need both to understand a new, utterly alien power—and to project a mastery of that power to the rest of the world. Beck and her colleagues at the DRI, under contract with the Department of Energy, have spent two decades cataloguing and studying these diverse remains—the rusted wreckage of towers that held bombs, seemingly mundane research support areas, instruments from specific experiments, mock suburban homes. The Test Site offers a complex archaeology of science and war, of geopolitics and popular culture.

In August 1945, the United States dropped nuclear devices over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, hastening the Japanese surrender that ended World War II. The blasts, very small by the standard of what would come, killed more than 100,000, injured and sickened countless more, and left two cities in ruin. Two months later, President Harry Truman told Congress that the atomic bomb signaled “a new era in the history of civilization.” He went on: “Atomic force in ignorant or evil hands could inflict untold disaster upon the nation and the world. Society cannot hope even to protect itself—much less to realize the benefits of the discovery—unless prompt action is taken to guard against the hazards of misuse.”

Congress reacted in 1946 by creating the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to oversee nuclear development. Responding to the threat of a Soviet nuclear program, the AEC authorized nuclear weapons tests in the South Pacific, and then later decided the Nevada desert would be less vulnerable to attack. In December 1950, the commission recommended establishing a permanent proving ground on a piece of the old Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range. Truman concurred, and the first atmospheric detonation at the Nevada Test Site, a one-kiloton bomb dropped on Frenchman Flat, took place a month later. The U.S. nuclear testing program continued for 41 years and included 928 nuclear tests (with 1,021 total detonations). Most were underground, but 100 tests were atmospheric, or out in the open. Today, as the Nevada National Security Site, it is still used for radioactive waste storage, first-responder training, “subcritical” nuclear tests, and other projects.

The nuclear explosions at the Nevada Test Site were largely clustered in four areas: Yucca Flat, Pahute and Rainier Mesas, and Frenchman Flat, which stands out for its concentration of aboveground remains. “As time passes, memories are fading about what nuclear weapons can do,” says Beck. “But when you go out there on Frenchman Flat, you can really see how powerful a nuclear detonation can be.”

The material remains at the Test Site represent just how little was known about the power and impact of nuclear weapons technology—even after it had been rushed into use in Japan. Subsequently, tests would be conducted to assess the effects of bombs, simulate nuclear warfare, better understand the effects of radiation, and, of course, build bigger and better bombs. Additional research efforts examined the storage of nuclear waste and the application of nuclear technology to missiles, space travel, and large-scale engineering projects, such as canals. On Frenchman Flat, many of the atmospheric tests were focused on “survivability,” specifically how different structures and materials respond to nuclear blasts. There are, for example, the remains of glass houses, a “motel” (to test structural partitions and masonry), a small house cheekily named “Joe’s Bar,” and dozens of other structures.

Beck was born a month after the Test Site opened 63 years ago. She conducted fieldwork in Peru and the American West before moving to Las Vegas in 1989. She joined the DRI the next year. “When I began, we were really only looking at prehistoric archaeology and at mining- and ranching-related facilities,” she says. Underground testing was still taking place when she started her work there, and part of her job was to identify Native American artifacts in areas scheduled for detonations.

It can be hard to imagine anyone actually living there, Beck says, in part because of lingering radioactivity and ongoing nuclear waste research, but evidence is all around. The variety of stone points found on-site shows occupation that goes back through the Paleoindian period to some 11,000 years ago. At a site called Midway Valley, DRI researchers found a quarry for chalcedony and obsidian that was used for thousands of years. And in Fortymile Canyon there are petroglyphs that some interpret as evidence of vision quests.

There are also later habitation sites for Native Americans, as well as for the prospectors, miners, and ranchers who arrived in the mid-nineteenth century. Often clustered around springs, such sites include seasonal camps, rock shelters, cabins, horse corrals, and water troughs, as well as mining equipment and the writer’s cabin of B.M. Bower, who wrote dozens of novels set in the American West.

“But one of the biggest thrills,” she recalls, “was to go into Frenchman Flat and look at the atmospheric-testing grounds. Within a year, it had become apparent to me that the remains at the site were significant historically but were being totally ignored.”

The Department of Energy agreed. In 1991, Beck worked with an architect to document her first twentieth-century structures, and she’s been doing Cold War archaeology ever since. Year after year, archaeologists from the DRI have walked transects across the vast landscape, documented historical remains, and conducted targeted surveys of buildings and structures—almost 2,000 sites so far, representing less than 5 percent of the Test Site. Documenting it all, Beck says, would take lifetimes. “You’d think that after more than 20 years we would have seen it all, but that’s far from the truth,” she says. “We still find things—it’s really amazing.”

At Frenchman Flat, Beck leads a visiting reporter through some of the remains, which are concentrated in about 4.5 square miles of dusty terrain. There, nuclear weapons were dropped by bombers, carried aloft by balloons, perched on towers, and fired from a cannon. Each nuclear detonation was part of a test series or “operation,” often consisting of dozens of “shots,” or explosions. Countless experiments and measurements were conducted and recorded, sometimes across multiple shots or operations.

For example, for one shot called Priscilla, a 37-kiloton weapon was detonated from a balloon 690 feet off the ground on June 24, 1954, as part of Operation Plumbbob. A structure that looks suspiciously like a bank vault remains on Frenchman Flat from that test. “Look how thick those walls were,” Beck says, approaching the twisted steel rods—once encased in concrete—radiating from its sides. The interior of the vault, however, survived intact. “Everyone jokes that they were trying to make sure the money would be safe after a nuclear blast,” Beck says. In fact, according to a 1957 government document, the vault was donated by the Mosler Safe Company “out of the concern on the part of banks and insurance companies over protection of records and valuables.”

Surrounding the vault in every direction are other battered and rusting ruins. A twisted train trestle sits atop two concrete blocks—what’s left of a railway bridge that endured two explosions. An airplane hangar has collapsed beyond recognition. An underground parking garage, included in tests to see how such buildings would perform as bomb shelters, is mostly intact. There is also a group of domed shelters made from concrete and rebar. Some are blown apart, others are not. “They were trying to see whether a dome shape would have a better survival rate than, say, a rectangular building” Beck says. Another feature on Frenchman Flat is an aluminum cylinder with two square holes cut into its side, lying horizontally and held upright by three steel plates. In Priscilla and other tests, pigs were used as human proxies. During the years of atmospheric testing, 1,200 pigs lived on the site in pens nicknamed the “Pork Sheraton.” Prior to detonations, some were placed in containers such as this and outfitted in a variety of fabrics to test how materials held up under intense heat.

But pigs weren’t the only ones exposed to radiation. During the 1950s, 60,000 troops passed through the Test Site. Wearing helmets, gas masks, and ordinary fatigues, many crouched in trenches during the blasts, and later advanced closer—simulating ground warfare in an all-out nuclear conflagration. Another shot in Operation Plumbbob, Smoky, a 44-kiloton device detonated on a tower on Yucca Flat, on the other side of the Test Site, on August 31, 1957, involved 3,000 U.S. servicemen on the ground.

After testing was conducted, many such atmospheric detonation sites were cleaned up, but Smoky was not. “This is the best intact atmospheric nuclear test site,” Beck says. “It makes it extremely special.” She and her team, wearing protective suits, recently conducted an archaeological assessment there. Primary among the remains are twisted fragments and stanchions from the 700-foot tower that held the Smoky device. Evidence of experiments remains, too: A few hundred scattered lead bricks had shielded some kind of instrumentation, and there are French- and German-designed personnel bunkers that were being tested. There is also a hill next to ground zero that is called the “Coke Hill” but is covered in charcoal, and another smaller hill behind it. As with a number of the structures the DRI has documented, no one knew what the hills were used for until engineering drawings finally turned up—they were earthen berms used to protect instrumentation. Despite extensive written documentation, there is much that is still unknown about some sites. “We believe in most cases the data exists somewhere,” Beck says.

More than anything, Beck and the DRI are adding a tangible component to this vast written record, much of which is classified. Their work provides another means of understanding a time defined by fear and uncertainty, but also optimism. It’s not, Beck says, that these materials are going to be lost, as the site is still heavily protected and most of the remains are durable. It is rather that they need to be found, and then inventoried, so that there is an index of knowledge as memories of the age of atomic experimentation fade.

Of more than 300 million U.S. residents, some 80 million were born after the 1992 testing moratorium. And less than a third of the population is old enough to remember the mushroom clouds of atmospheric tests that rose over the Nevada desert. “I’m not sure how any people, even my kids, can grasp what it was really like,” Beck says, thinking back to the time when nuclear anxiety permeated daily life. She sees her work as preserving at least a glimpse of that era.

-

Dawn of a Thousand Suns November/December 2014

Surviving Doom Town

(National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Site Office, U.S. Department of Energy)

(National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Site Office, U.S. Department of Energy) -

Dawn of a Thousand Suns November/December 2014

Going Underground

(Science Source/Getty Images)

(Science Source/Getty Images) -

Dawn of a Thousand Suns November/December 2014

Peace Camp

(Courtesy Colleen Beck, Desert Research Institute, and National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Site Office, U.S. Department of Energy)

(Courtesy Colleen Beck, Desert Research Institute, and National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Site Office, U.S. Department of Energy)