When the emperor Hadrian visited the province of Britannia in A.D. 122, he was in full command of the entire Roman Empire, which stretched some 2,500 miles east from northern Great Britain to modern-day Iraq, and 1,500 miles south to the Sahara Desert. He had become emperor five years earlier, after a controversial postmortem adoption by his predecessor and guardian Trajan, and he ruled until his death in 138, at the age of 62, likely of a heart attack. In just over 20 years, he became, according to an anonymous ancient source, the “most versatile” of the Roman emperors. He was a battle-tested solider who fought with Trajan in Dacia, a skilled politician who masterminded the consolidation of the empire’s territory, a faithful patron and lover of the arts, and a tireless traveler who visited nearly half the empire during his reign.

Hadrian is perhaps best known, however, as one of Rome’s most prodigious builders. In this he followed in the emperor Augustus’ footsteps as a ruler who grasped architecture’s inherent ability to express ideology and power. For most of Hadrian’s reign, the empire was at relative peace—the Pax Romana, or “Roman Peace,” was at its height. Thus he didn’t achieve the notable military victories of some of his predecessors. Instead, he turned to art and architecture as a way of legitimizing his rule, demonstrating Roman dominion, solidifying his legacy, and leaving his enduring stamp on the landscape of the empire.

In Rome itself, the emperor sponsored numerous building projects, both to enrich the lives of its citizens and tie himself to the city’s past. At the site of the Pantheon, the spectacular domed temple in the heart of Rome that Hadrian is credited with completing, he linked his own rule to one of Rome’s most revered men, the first-century B.C. consul Marcus Agrippa—a great builder in his own right. Hadrian chose to retain the facade of Agrippa’s much earlier temple on the front of the Pantheon, while at the same time providing a new venue for the worship of all the gods. Hadrian also designed what is thought to have been the largest temple in ancient Rome, an enormous edifice honoring the goddess Venus Felix, a “bringer of good fortune,” and Roma Aeterna, or “Eternal Rome,” a double dedication whose symbolism, like the immense temple itself, was impossible to miss. Outside Rome, Hadrian displayed his personal love of all things Greek, and he combined it with the clear message that Rome was now in charge. In Athens, for example, he restored the Greek Olympieion, or Temple of Olympian Zeus, and erected a new gold-and-ivory statue to the god, but also placed four statues of himself in front of the main shrine and a large Roman-style arch at the entrance to the temenos, or sanctuary.

In the provinces, as in Rome, architecture served symbolic as well as utilitarian purposes. Hadrian sponsored the renovation of ancient cities such as Smyrna, now Izmir in modern Turkey, founded entirely new ones such as Antinoopolis in Egypt, and commissioned the construction of public architecture—theaters, temples, arches, municipal buildings, and countless statues and inscriptions—everywhere he went. These sites often exhibit a mix of local and imported styles and tastes, and brought what Duke University historian Mary Boatwright calls a “‘Roman’ visual vocabulary” to much of the empire, uniting the vast territory in a way that proclamations and policy often could not. But there was one place where the emperor thought something entirely different was required.

By the time Hadrian visited Britannia, his plan to end Trajan’s policy of extending the empire’s territory at all costs had already played out in Mesopotamia, where he had ceded newly conquered lands east of the Euphrates River and restored the border to its previous location. In this, too, he followed Augustus, who had espoused the principle that borders should be defendable, and, whenever possible, formed by natural boundaries, such as the Euphrates, the Rhine and Danube Rivers, and the Atlantic Ocean. But Great Britain has no broad rivers running through its center to delineate the border between the province of Britannia and the lands north, which were occupied by indigenous Celtic tribes with whom the Romans often came into conflict and who, early in Hadrian’s reign, were in rebellion.

Hadrian decided that the only solution was to build a wall. There were already man-made fortifications along parts of the empire’s other frontiers, mostly constructed of timber, earth, and turf. But on no other frontier did an emperor construct a wall made almost entirely of stone—the formidable edifice now known as Hadrian’s Wall, much of which survives to this day.

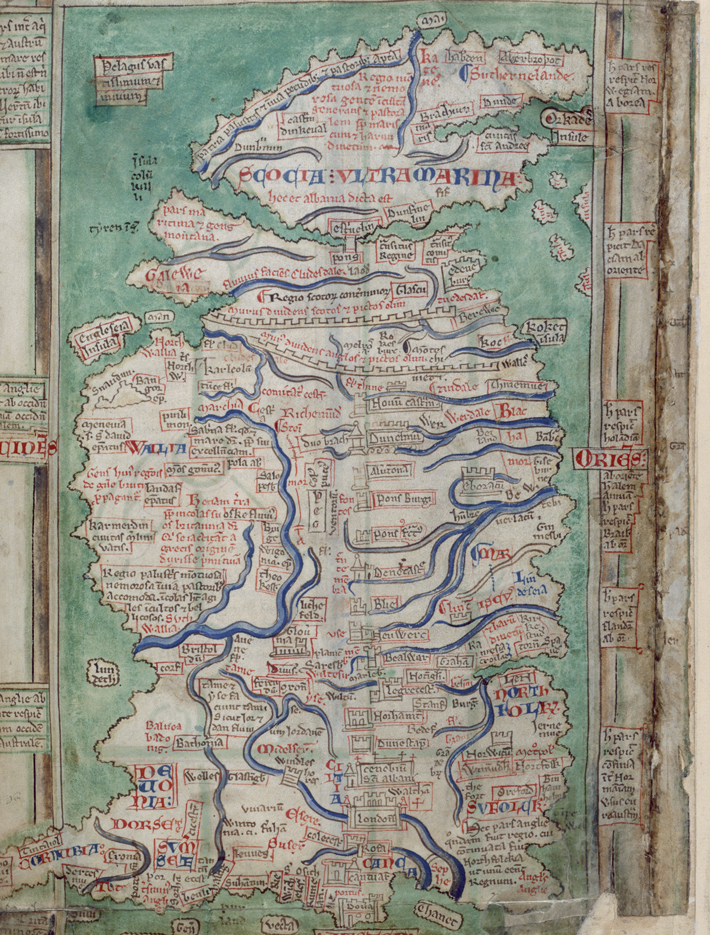

Hadrian’s Wall spanned 73 miles, or 80 Roman miles, the entire width of the island, from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west. At first the eastern part of the wall was built of stone, the western half of turf and timber, but the plan for the wall changed soon after it was begun. Its overall width was reduced to about eight feet, or even less in some places depending on the terrain, and the 30-mile turf-and-timber section from Bowness east to the River Irthing began to be replaced by stone, though this modification would not be completed for decades.

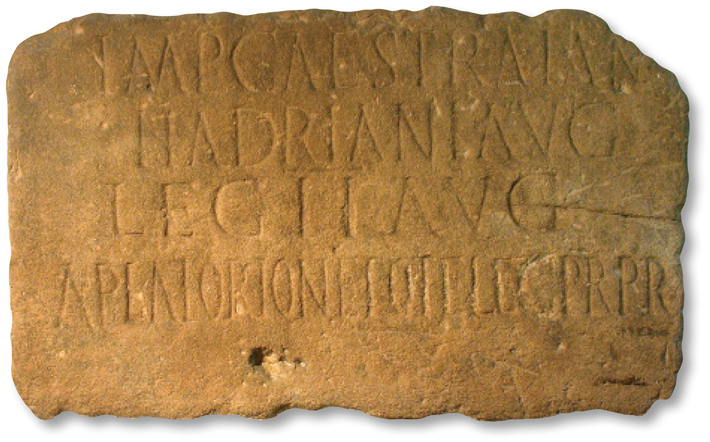

The majority of the construction was accomplished in six years, mainly by 15,000 troops from the three Roman legions stationed in Britain at the time—the II Augusta, VI Victrix, and XX Valeria Victrix—along with some members of the Roman fleet, using the ample supply of local stone as well as the natural features of the landscape, and largely without the use of mortar. The medieval monk, historian, science writer, and theologian, the Venerable Bede, describes the wall as standing 12 feet high, although some archaeologists believe it might have once stood a few feet higher. At each Roman mile along the span, there was a fortified milecastle, and between each milecastle were two observation towers. There were also forts, likely 16 in total, spaced about seven miles apart. To augment its effectiveness and create a military zone, a 19-foot-deep by 10-foot-wide ditch with mounds flanking it, called the Vallum, was constructed south of the wall. A 10-foot-deep, 28-foot wide, V-shaped ditch was dug on the north side of the wall as an additional defensive measure. When fully manned, not by the legions that built it, but by regiments of auxiliary infantry and cavalry drawn from the provinces, at its height under Hadrian, nearly 10,000 soldiers were stationed on the wall.

Much current archaeological and historical research on Hadrian’s Wall centers on the question of its purpose. At first, this might seem obvious—if there are troublesome tribes to the north, and you want to keep them out, you build a strong defensive wall. In fact, the late-Roman author of Hadrian’s biography in the Historia Augusta states that Hadrian “was the first to build a wall 80 miles from sea to sea to separate the barbarians from the Romans.” But this undoubtedly biased view is not the only possible answer, and, as with his other construction projects across the empire, Hadrian likely had multiple objectives in mind. The wall was also built to keep people in, within the confines of a Roman province. It allowed the Romans to direct civilian traffic in and out of the empire, a powerful weapon in exerting economic control over those wishing to obtain access to Roman markets. Construction and maintenance of the wall provided years of work for thousands of soldiers who, particularly until near the end of the second century, had very little to do owing to the relative quiet that prevailed across the empire. Idle, bored soldiers—who are already being paid—are never a good thing. Furthermore, the Roman legions had all the expertise required to build the wall as they traveled with their own surveyors, engineers, masons, and carpenters.

Beyond its practical purposes, the psychological impact of the wall must have been tremendous. For nearly three centuries, until the end of Roman rule in Britain in 410, Hadrian’s Wall was the clearest statement possible of the might, resourcefulness, and determination of an individual emperor and of his empire.

The Roman conquest of Britain began in earnest in the mid-first century A.D. Although the Romans had first come to the island a century earlier, rebellions had pulled Julius Caesar back to the continent. Britain remained free until A.D. 43, when the emperor Claudius led an invasion force of as many as 40,000 legionary and auxiliary troops. The complete subjugation of the island would take decades, but from that point on, the Roman army left its permanent mark.

At the time of the construction of Hadrian’s Wall, there were likely about 35,000 Roman soldiers in Britain, and twice as many people associated with military installations there. Assuming a total population on the island of around one to two million people, as much as 10 percent of its inhabitants were supported by the empire. This, explains archaeologist Andrew Birley, had a tremendous impact on the environment, trade, economics, law and order, governance, and, indeed, every aspect of life. Although its effect on some segments of society, such as the native population of Great Britain, is not well understood, a great deal has been learned, particularly over the last 100 years, from excavations of sites on and associated with the wall. Hadrian’s Wall is a microcosm of the Roman world—its military strategy, building techniques, material culture, and the lives not only of its soldiers, but also of the thousands of men, women, and children who lived on the empire’s northern frontier.

-

The Wall at the End of the Empire May/June 2017

Defensive Strategy

(Courtesy English Heritage)

(Courtesy English Heritage) -

The Wall at the End of the Empire May/June 2017

Where Were the Stables?

(Courtesy English Heritage)

(Courtesy English Heritage) -

The Wall at the End of the Empire May/June 2017

The Other Wall

(Douglas Carr/Alamy)

(Douglas Carr/Alamy) -

The Wall at the End of the Empire May/June 2017

Feeding the Army

(Courtesy Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums)

(Courtesy Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums) -

The Wall at the End of the Empire May/June 2017

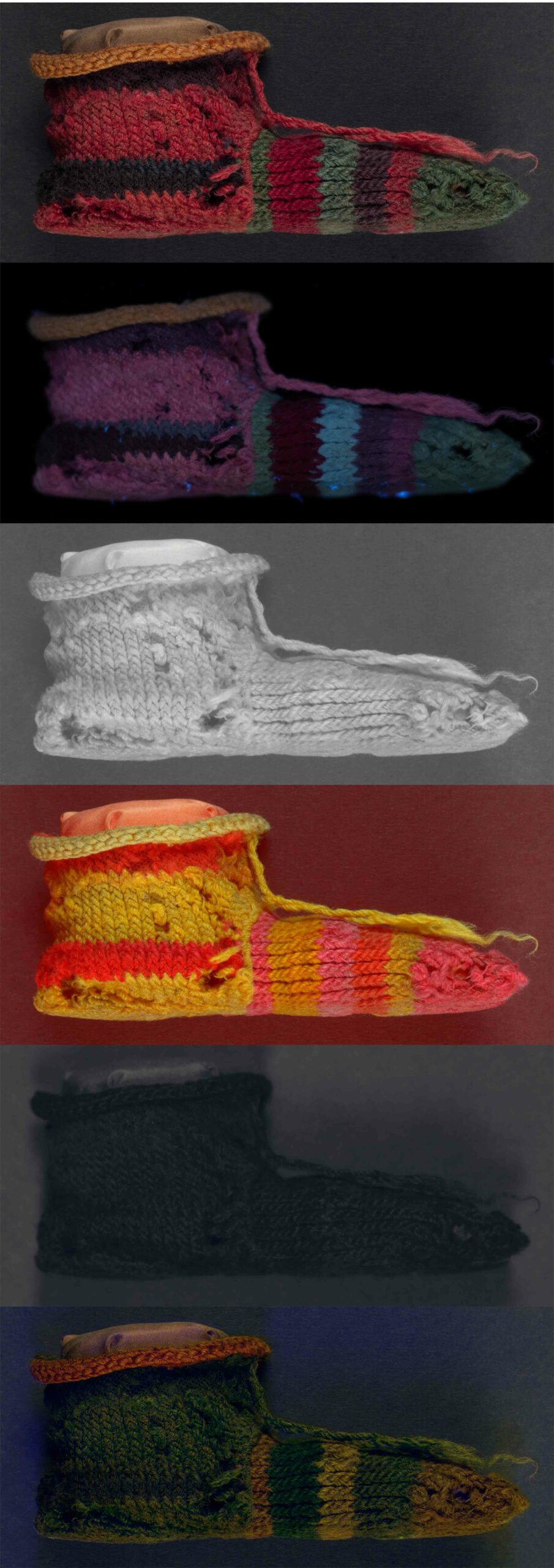

Life on the Frontier

(Courtesy Vindolanda Trust)

(Courtesy Vindolanda Trust) -

The Wall at the End of the Empire May/June 2017

The Ritual Landscape

(Courtesy English Heritage)

(Courtesy English Heritage)