In 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and 400 of his men marched into the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and knew at once they were in a strange and wondrous place. Even before their arrival, the emperor Moctezuma II had sent the Spaniards lavish jewels and fine clothes. He may have believed the Spaniards to be the deity Quetzalcoatl, the “plumed serpent,” returning to Tenochtitlan from the east, or he may have thought he was receiving emissaries from a friendly state. According to their own accounts, as the Spaniards began to explore the city, they found temples soaked with blood and human hearts being burned in ceramic braziers. So thick was the stench of human flesh, wrote chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo, that the scene brought to mind a Castilian slaughterhouse.

Yet what made an even greater impression was Tenochtitlan’s bustle and press. Streets were so crowded that the Spaniards could barely fit through them. And the hubbub of the main plaza, full of shouting salesman offering everything from beans to furniture to live deer, could be heard miles away. “Among us there were soldiers who had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople and all of Italy and Rome,” wrote Díaz. “Never had they seen a square that compared so well, so orderly and wide, and so full of people, as that one.”

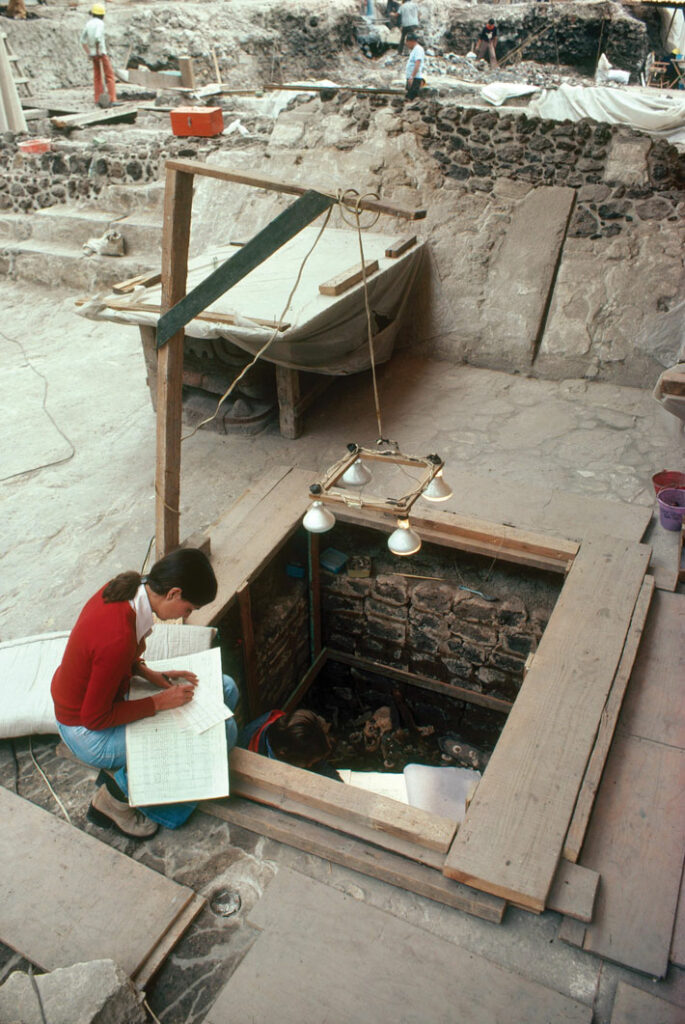

Five hundred years later, Mexico City’s main plaza still teems with shoppers and street hawkers, while, only a block away, archaeologists are carefully digging up the remains of the city Cortés and his men wondered at. Today archaeology is happening everywhere in Mexico City—just off the main square, in alleys, patios, and back lots. One dig is being conducted in the basement of a tattoo parlor. Others are going on beneath the rubble of buildings destroyed in the city’s 1985 earthquake. There’s a site located in a subway station, and two others are under the floor of the Metropolitan Cathedral. When city workers repave a street, archaeologists stand by to retrieve ceramic sherds, bones, and other artifacts that appear from under the asphalt. Excavation sites are often so close to modern infrastructure that archaeologists have to take care not to undermine modern building foundations. Researchers regularly contend with a bewildering network of sewers, pipes, and subway lines. And because the Aztec capital was built on a filled-in lake bed, they often have to pump water out when these areas flood.

Templo Mayor, 1978In 1978, workers laying electrical cables accidentally discovered the Aztecs’ Templo Mayor, or High Temple, two blocks from the city’s central square, Zócalo. In 2011, a major ceremonial cache was discovered under the Plaza Manuel Gamio. Since these serendipitous finds, ongoing excavation and research by the National Institute of Anthropology and History’s Urban Archaeology Program (PAU) have changed our understanding of Aztec society. Excavations at five sites in particular, all within short a short walk of each other, have begun to crystallize our understanding of daily life, worship, and governance during the height of Aztec rule.

Scholars now understand that the human sacrifices that once shocked the Spaniards were not conceived as public horror or punishment, but rather as reenactments of Aztec society’s own creation. Archaeologists have excavated stone carvings with depictions of violent myths, some featuring people being dismembered or thrown from great heights. And human remains subsequently uncovered show similar wounds, suggesting that the myths were played out atop the temples with actual people. According to Raúl Barrera, PAU director, “The Aztecs materialized their beliefs about creation, performing them at the Templo Mayor.” In ways barely intuited by the Spaniards or even by modern historians until recently, the Aztecs, also known as the Mexica, believed that the fate of the world rested on what happened on the towering heights of their temples. “The Templo Mayor was their holiest place, but, more than that, it was the center of the Mexica universe. It was from there that they made contact with the divine world and with the underworld,” says Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, archaeologist and professor emeritus at the Templo Mayor Museum.

Throughout downtown Mexico City, archaeologists have found some 40,000 artifacts, including mirrors made of shiny obsidian, Pacific turtle shells that were much-prized by the Aztecs, and precious jade-and-turquoise masks, all of which attest to the empire’s wealth. Other objects—mollusk shells from the Pacific, Caribbean shark teeth, jade from southern Mexico—have given researchers a richer understanding of the prosperity of trade ties forged by the Aztecs under the emperor Moctezuma’s fierce predecessor, Ahuítzotl, who ruled from 1486 to 1502. He added lands as far away as Chiapas to the city’s sphere of influence, conquered rich cacao-producing areas, and opened up trade ties with both coasts. Tribute poured in from vassal states.

Aztec Codex, 1519Although much has been learned about the Aztecs, the question of how this formidable empire fell to the Spaniards in only a few weeks of fighting continues to vex historians, and excavations in their capital have added little information to the debate. Despite new research highlighting the possible role of disease brought by Europeans, Mexican archaeologists believe the key factor was the resentment the Aztecs’ neighbors felt toward them. “The Spaniards were joined by thousands of indigenous people who were enemies of the Aztecs. Why? Because they were sick of paying tribute. They saw Cortés as their salvation,” says Matos Moctezuma. But before the Aztecs’ collapse, Moctezuma and Cortés shared a brief moment of friendship. Díaz wrote: “Moctezuma took [Cortés] by the hand and told him to gaze over his great city and the many others all around the lake.” He then invited Cortés to climb the Templo Mayor to get a better view. Within two years of that moment, Moctezuma’s great city was gone. Only now are archaeologists learning how much of it actually survived and is sitting beneath the paving stones and buildings that make up Mexico City today.

-

Under Mexico City July/August 2014

Templo Mayor

(Getty Images)

(Getty Images) -

Under Mexico City July/August 2014

Plaza Manuel Gamio

(Roger Atwood)

(Roger Atwood) -

Under Mexico City July/August 2014

School of the Ancient Elite

-

Under Mexico City July/August 2014

Temple of Quetzalcoatl

(Roger Atwood)

(Roger Atwood) -

Under Mexico City July/August 2014

Last City of the Aztecs

(Roger Atwood)

(Roger Atwood)