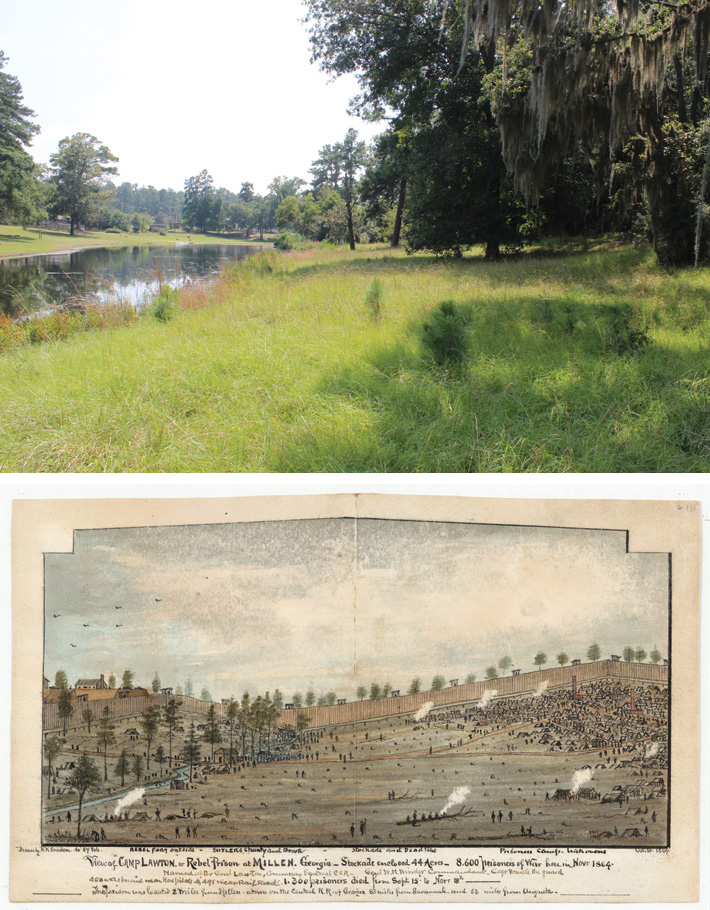

Camp Lawton had been on the mind of John Derden, a professor emeritus of history at East Georgia College, for decades, ever since he visited Magnolia Springs State Park in 1973. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources had turned the springs, which produce seven million gallons of crystal-clear water a day, into a state park in 1939. Some 200 miles southeast of Atlanta, Magnolia Springs is also the location of Camp Lawton, a surprisingly undisturbed Civil War site, where Confederate forces, for a brief time, imprisoned Union enlisted men.

“When I made that first visit, I saw a tablet in the park about the camp,” Derden recalls. He discovered that some rudimentary archaeological surveys—a few shovel tests over the years—had essentially turned up no remains from the nineteenth century. Only some of the surrounding earthworks, where manned munitions had been mounted and aimed menacingly toward the prison population, still stood. Derden, like pretty much everyone else, assumed no significant remains were left to help advance any chronicle of the camp and its inhabitants.

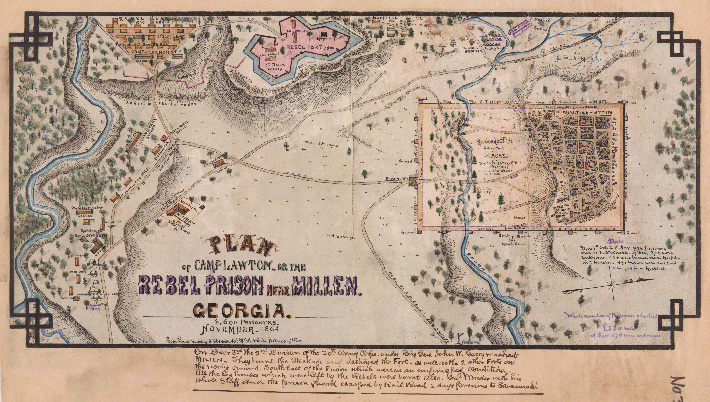

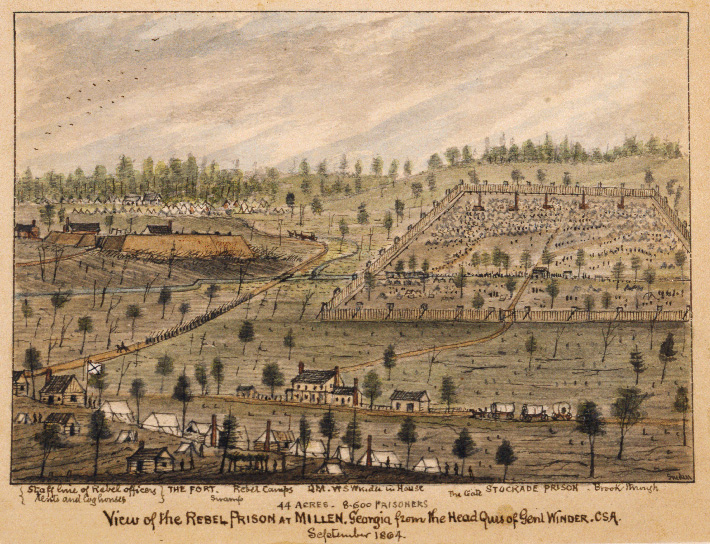

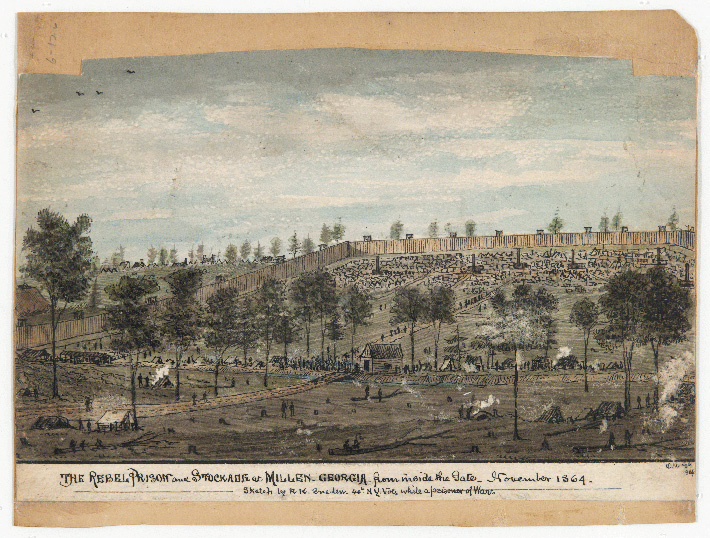

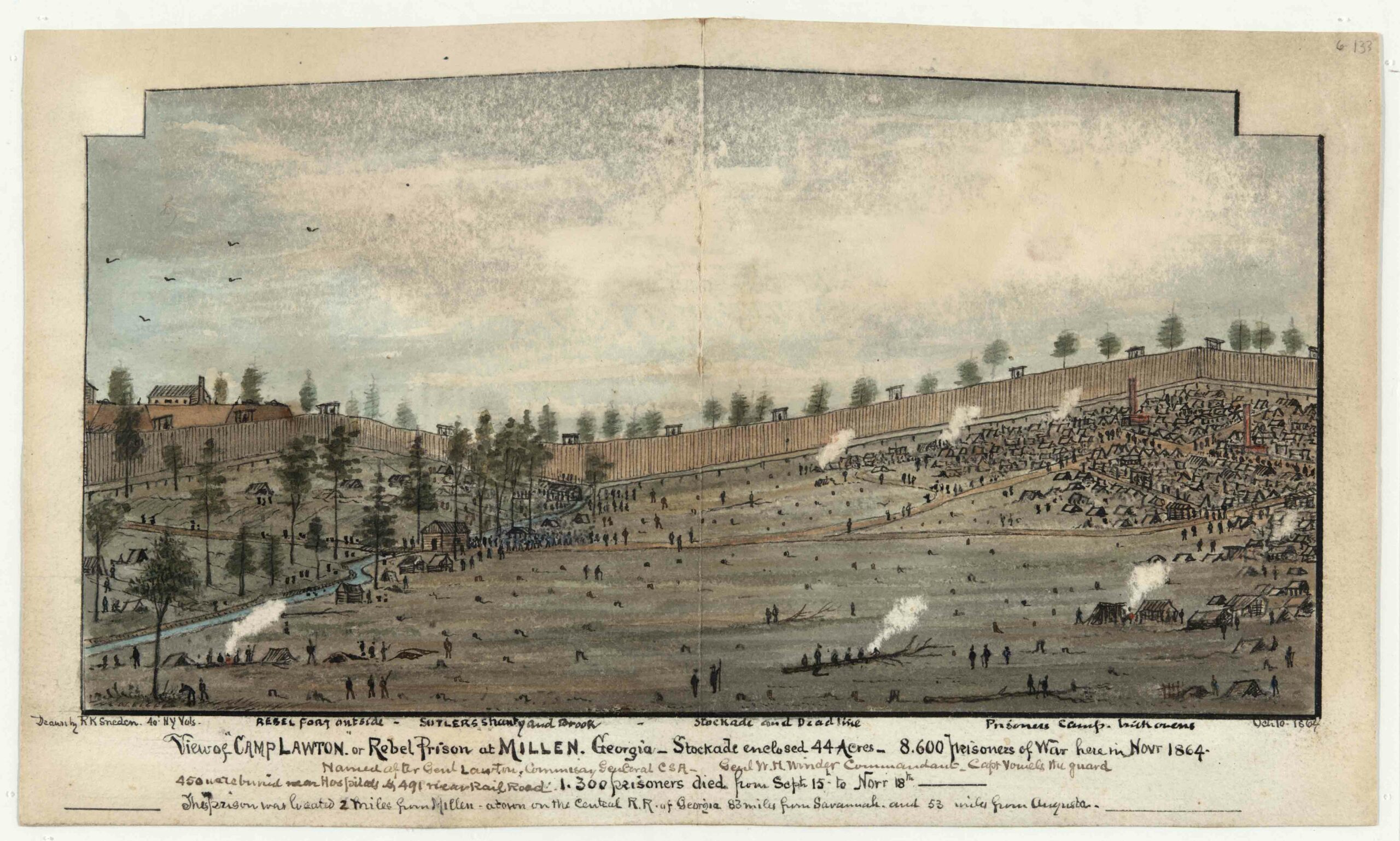

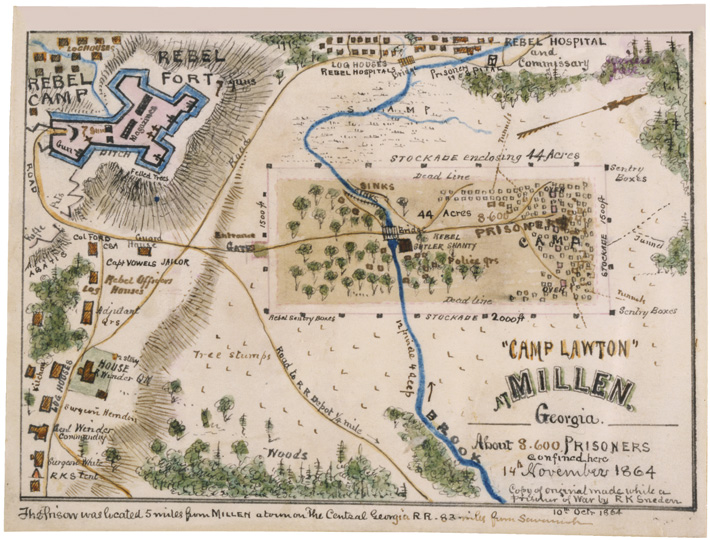

Nonetheless convinced of a worthy narrative, Derden plugged away at putting one together, relying on other sources, such as diaries and letters from the time, including the drawings and accounts of Private Robert Knox Sneden, a Union prisoner in the camp. Derden’s research revealed that Camp Lawton, a functioning prison for only six weeks, would end up being burned to the ground at the hands of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman in December 1864 as the Civil War drew toward its end. The prison had held upwards of 10,000 individuals on more than 42 acres fortified by an imposing pine-log stockade. Of those 10,000 Union prisoners, more than 700 died during their brief time at Camp Lawton. The survivors were evacuated in a hasty nighttime maneuver just one month before Sherman swept through the region. After these events, the camp was pretty much forgotten.

Derden’s scholarship resulted in a completed manuscript, The World’s Largest Prison: The Story of Camp Lawton. As it was about sent to the publisher in 2010, in an interesting twist, Derden and other historians, archaeologists, Civil War buffs, and locals were stunned to learn that Kevin Chapman, a graduate student at nearby Georgia Southern University, just 40 minutes down the road from the site, not only had discovered intriguing Civil War–era artifacts, but also had successfully located pieces of the prison’s burned stockade wall. As news hit The New York Times, CNN, and other national outlets, Derden had just enough time to tuck a final chapter into his book. Excavation of the site then cranked into full gear, led by Lance Greene, an assistant professor of anthropology at Georgia Southern, with Derden serving as an ad hoc adviser and expert. Archaeological evidence can now be brought to bear on nuances of daily subsistence in a community that existed for a mere month and a half in the fall of 1864. “This might be the last chance to look at a debate that still rages,” says Greene. “Who was to blame for dying prisoners? Were Confederates trying to starve them out?” Looking for answers to these questions is just a piece of the effort. The archaeologists are also searching for clues as to whether life was better or worse, depending on which side of the stockade wall a person found himself.

Confederate Brigadier General John H. Winder, ultimately promoted to commissary general of prisons east of the Mississippi, established his headquarters at Camp Lawton, reckoning it was “the largest prison in the world.” Its inmate population, guards, administrators, and all the rest, almost to a person, had been relocated from the notorious Camp Sumter, familiarly known as Andersonville, on the other side of the state. Even in its day, Andersonville was widely held as a symbol of POW suffering at its worst. Of the 45,000 Union prisoners that passed through its gates, 13,000 died of dysentery, scurvy, starvation, or violence at the hands of Confederate guards. Winder and other Confederate leaders hoped to alleviate the inhumane overcrowding and the ever-worsening conditions. In the summer of 1864, they accelerated the design and construction of Camp Lawton, which would be twice the size of Andersonville and located near the town of Millen.

Nearly 150 years later, Greene and his team are trying to determine if Camp Lawton did in fact improve prisoner conditions, as Winder said he intended. A seemingly endless array of artifacts—fistfuls by the day are pulled from the earth at several dig sites—is providing the clues to figuring out what life at Camp Lawton was like. The team, says Greene, is currently conducting large-scale excavations that are uncovering the exact locations and construction techniques of both the stockade and structures outside it, as well as personal shelters called “shebangs” that Union prisoners built within its walls. “We have identified what we think was a Confederate barracks area outside the stockade and that will let us compare the lives of prisoners and Confederate soldiers,” says Greene. “We hope to find out about the food they ate, and if they traded with their captors.”

Camp Lawton is unique among Civil War POW sites in that almost the entire length of the stockade is largely intact. Little archaeology has been done at Andersonville, for instance, because, as elsewhere, looters took much of what remained immediately following the war. “As far as we can tell, only the northwest corner of the stockade at Camp Lawton has been disturbed—by road construction of a four-lane highway,” Greene explains. “There are no other POW camps with this kind of preservation. The scale of what is at Lawton is enough for years of work.”

By 9 a.m. the temperature breaks 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Its partner in midsummer misery-making, humidity, hangs so heavily that breathing seems a chore. Squadrons of no-see-ums, gnats, and mosquitoes, trademark pests of the rural deep South, bite through multiple applications of insect repellant. About a dozen Georgia Southern students mop away streams of sweat and gather their shovels, trowels, buckets, screens, measures, and notebooks. In the oppressive heat, they scoop up and sort out the remains of Camp Lawton.

So far, the site hosts three separate excavation areas, two of which are within Magnolia Springs State Park. The third dig site is on adjacent wooded land north and west of the park that was formerly a U.S. Fish and Wildlife hatchery. This is where the forgotten shebangs, constructed of bricks by Union prisoners, were found. The team refers to this location as the “Federal side,” and, so far, it has offered up the greatest number of artifacts. Archaeologists have found numerous buttons, both military and civilian; suspender buckles; 1864 pennies, grocer’s tokens, and other coins; a picture frame; and tin cans and lids.

The stockade that encompassed the Federal side, and encloses part of the current Magnolia Springs, was massive. Most of the prisoners likely lived on the Federal side, where the land was higher and drier. Drawings made by Sneden during his short time at Camp Lawton confirm this. He depicts the bulk of prisoner squats as concentrated in the northern section of the stockade. Greene notes that the Sneden drawings have been a “wonderful resource” for the team, especially in providing a general layout for the site. As Sneden drew it, the stockade was rectangular. “Because his goal was to show the entire camp in a few drawings, he did have to skew the landscape a bit,” Greene says. “The hills are a little more prominent and things are pushed together.” Archaeologists are now working to identify the precise location of the corner in the southern section. They should then be able to tell if the stockade was actually square, as most of them believe it was, rather than rectangular.

EXPAND

Camp Lawton’s Stockade and Forgotten Population

Camp Lawton is unique among Civil War prisons because the remains of its stockade are largely undisturbed. Its condition offers the Georgia Southern team investigating the camp an unprecedented opportunity to learn about its boundaries and construction, and about those who built it.

Graduate student Hubert Gibson is excavating on the park side of the prison site, looking at trenches that were dug to accommodate the stockade. “We know from oral histories and newspaper accounts that approximately 500 slaves and 300 prisoners worked here,” Gibson says. These slaves would have been conscripted from nearby plantations to help fell trees, dig trenches, and secure the 15-foot-tall stockade posts with backfill. By comparison, Gibson explains, there is more information about prison construction at Andersonville. Archaeologists know, for instance, that prisoners built the northern extension of that stockade and that slaves did the rest. Their work, Gibson notes, was better. “I think most of the slaves were from the local area, and their experience working on irrigation ditches, fence posts, and other agricultural landscaping would have promoted familiarity with soil composition and a knowledge of good construction techniques in local soils.”

At Camp Lawton, that same knowledge was critical. The portions of the pen on the Magnolia Springs State Park side of the site were likely easy to erect, as there is plentiful Georgia red clay a few feet below the soil that could have been used to stabilize the posts. Stockade remains on the Federal side, Gibson says, show that that location presented more of a challenge. “On the Federal side, the clay content is very low. Most of the soil is a coarse sand,” he says. “You could dig two meters into the ground and not hit clay.” The slaves, he continues, likely carted clay over to these areas to stabilize posts, which is evidenced by a foreign clay layer packed next to where Federal side posts once were. “It is evident,” Gibson says, “that slave laborers were thinking about obstacles to construction and how to solve them.”

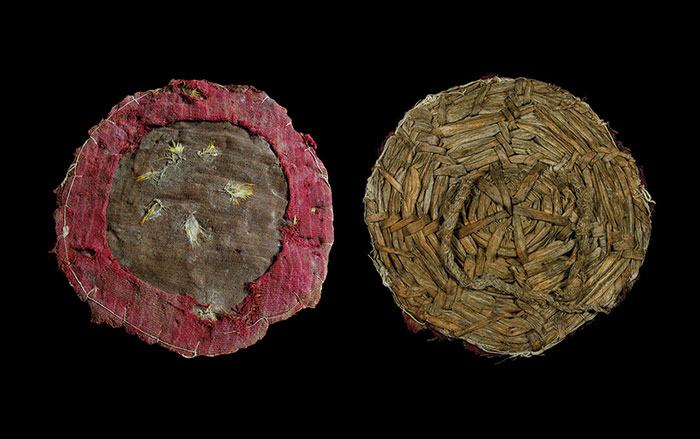

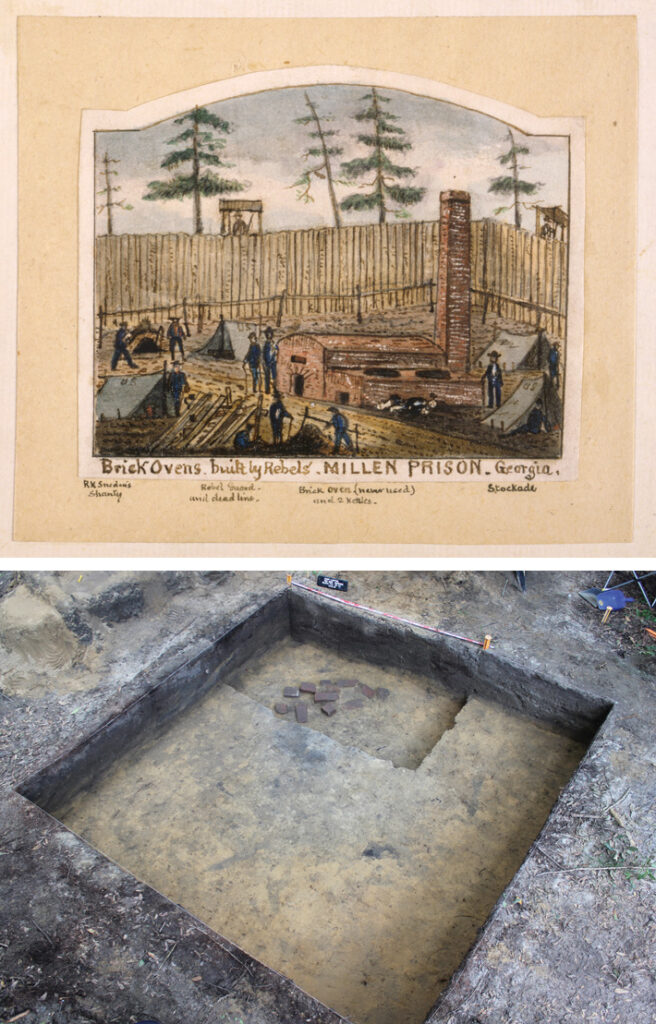

With Sneden’s drawings as context, evidence from the digs is allowing a rough but poignant understanding of prisoner life to emerge quickly. The bricks that prisoners used to build their shebangs inside the stockade were first thought to be the remains of five or more large ovens that were known to have been provided by the Confederates for prisoners to cook their rations. However, according to Greene, the prisoners never cooked in them. Graduate student Ryan Sipe notes, “Now all evidence points to prisoners stealing bricks from the ovens to use in their own shebang construction.” To build these shelters, prisoners would dig a shallow pit and line it with bricks. They would then drape a blanket over it, tent-like, using rope and sticks, or construct a crude lean-to. A firm foundation on the ground seems to have been the most comfortable shelter a prisoner could expect. While seemingly minimal, it was a step up from Andersonville, where the ground was vermin-infested and overcrowding meant that 10 men might share headroom under makeshift tents.

Excavators are going down in roughly four-inch increments in the shebangs, where they’ve discovered charred animal bones. The team expects further screening of the dirt to turn up more bone fragments. Testing will determine if prisoners, hunkered down in their pitifully threadbare quarters, ate bones that had been softened by fire. If that’s the case, it would verify that the meat rations for inmates were indeed minimal cuts.

Greene’s excavations have also turned up railroad spikes. Spikes could be filed down and used for digging tools, but it is not clear how the prisoners would have acquired them. Nearly all prisoners were transported by rail from Andersonville. They might have changed trains several times before arriving at the Lawtonville stop, a half-mile march from their new place of imprisonment. While in the shuffle of being boarded on and off rail cars, captives could have helped themselves to whatever debris might have seemed to be of use.

Greene has also found spoons, about four inches long, with the handles bent at almost a 90-degree angle, no doubt used as “a tool of some kind.” The team has also located parts of scissors, pockets knives, lead bullets carved into nipples to keep powder dry, bullets cut for chess pieces, heel taps, key rings, knapsack hooks, and many service buttons (usually marked by the manufacturer and, hence, easy to trace). Electrolysis labs, some set up in the field, are removing rust from the metal artifacts, and a local veterinarian has volunteered to X-ray some of the more fragile and excessively rusted items.

By contrast, much of what has been found on the Magnolia Springs side of the excavation is on land that formerly surrounded the pen and was not occupied by prisoners. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the area was occupied by Confederate forces during this period, as opposed to being used for farming or as civilian homesteads. Greene says the team is finding a lot of cut nails, typical of nineteenth-century construction, indicating there were once wooden buildings there, likely Confederate barracks for enlisted men or the Camp Lawton headquarters. “The Sneden maps and diary show that there were a lot of military buildings between the Lawtonville railroad depot and the stockade,” Greene explains. “Also, there are several artifacts that we recovered that appear much more commonly on Civil War–era military sites than on farmsteads from the period.” For example, a percussion cap from a rifle, a brass keg-tap, the brass cylinder from the end of a large parasol or tent, and early rifle cartridges all suggest a military presence. “We are also finding shoe eyelets, horse tack, bridle rings, undecorated whiteware, pottery sherds, and glass,” he notes.

The enormous disparity in the types of archaeological remains found inside and outside the stockade points to very different lifestyles for Union prisoners and Confederate soldiers. Sneden, in his journal, confirms that prisoners didn’t have any ceramics or glass. “So they used tin cans instead,” says Greene. “And we have found lots of those, although not always in good shape because the soils are so acidic.”

The idea that the lives of prisoners were much worse than those of their captors at a POW camp seems like a safe assumption to make. But archaeological evidence from another Civil War prison camp, Johnson’s Island, Ohio, in Lake Erie, where Union forces held Confederate prisoners from 1862 to 1865, suggests that wasn’t always the case. David Bush, professor of anthropology at Heidelberg University in northern Ohio, says of his 25 years of investigation at the site, “We don’t have a lot of dialogue on the how and why, but the results speak to a desire for Johnson’s Island to be humane housing—soldier housing as for any soldier.”

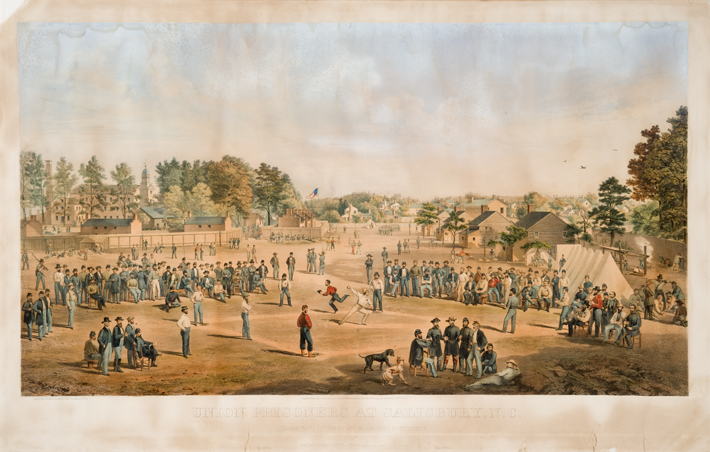

By contrast with Camp Lawton, contract labor built 13 wooden buildings at Johnson’s Island, complete with cook stoves, heating stoves, windows, and bunk beds in each. What’s more, the detained Confederate occupants, mostly officers, furnished themselves with china, crystal, fine cutlery, and other high-end accoutrements to which they were accustomed. They received $100 checks from home and could spend lavishly on whatever the sutler, the civilian grocer located within the camp, offered. “We don’t have archaeological records for their guards, but it is my hypothesis that there was a disparity, that the guards had a lesser lifestyle than the prisoners,” says Bush. After all, the guards earned only $13 a month.

Bush says he’s anxious to see what will come up at Camp Lawton. The discovery of the shebangs, in particular, interests him. It creates a basis for comparing lifestyles in a tight time period and is useful for seeing how prisoners tried to tend to their own well-being. Derden notes that Bush’s work at Johnson’s Island turned up examples of ingenuity among the POWs, such as the manufacture of hard rubber jewelry while confined. “As the Camp Lawton dig continues, I think we will see more evidence of resourcefulness—already we see it in the pilferage of bricks.” In addition, and as important, Derden says, “The textual and archaeological exploration of Camp Lawton will allow us to examine the prison economy, an economy that involves the camp sutler, as well as trading between guards and inmates, and inmates and inmates.” Says Eric Leonard, chief of interpretation and education at Andersonville National Historic Site, “Prisons are an entry point to giant stories.”

It is hard to imagine, in this weather, which wilts humans but nourishes corn, peach trees, and other crops, where birdsong and train clatter drift through the woods, that part of the hardship at Camp Lawton came from a freak freeze. A snowstorm lashed the prison close to the time that the short but eventful life of the camp was extinguished.

Slideshow: A Civil War POW Camp in Watercolor

On November 27, 1863, Union Private Robert Knox Sneden was captured by soldiers under the command of Confederate leader John Singleton Mosby at Brandy Station, Virginia. It would mark the beginning of a year of captivity for the topographical engineer-turned-mapmaker. He would spend six-and-a-half months at the infamous Andersonville prison in southwest Georgia, a site that would come to symbolize the brutal suffering of the Civil War.

Almost a year after his capture, Sneden was paroled and left under the supervision of Isaiah White, a physician serving Camp Lawton, a newly built POW camp in east Georgia where Sneden had been transferred two months earlier. During his short stint there, Sneden produced several drawings of the prison and its surrounding environs. He would later turn these into watercolors once he returned to New York after the war. “In exchange for promising not to escape, Sneden worked as a clerk for an army surgeon at Camp Lawton," says Andrew Talkov, head of program development at the Virginia Historical Society, which keeps an archive of 5,000 pages from Sneden's personal memoirs that includes the Camp Lawton paintings. "Because of that position, he had greater liberty to move freely around the camp."

Sneden's paintings offer insights about the construction of the prison, how the prisoners lived within it, and the layout of the Confederate encampment that surrounded it. The artwork helped to orient the archaeologists excavating Camp Lawton nearly 150 years after its brief stint holding prisoners of war. “Sneden’s drawings give us imagery in many cases where imagery doesn’t otherwise exist," says VHS lead curator Dr. William M. S. Rasmussen. "Sneden had an incredible visual memory and he combined it with notes and sketches he made in the field to produce an impressive visual record of life during the Civil War.”