It is the night of October 31, and hundreds of people have gathered at the Hill of Ward, once known as Tlachtga, in County Meath, Ireland. Some wear robes and masks and carry torches and banners emblazoned with spiritual symbols. It is all part of a revival of the ancient Celtic festival called Samhain (pronounced “SAH-win”) that includes processions, chanting, and storytelling. “Let’s raise our voices together and call back Tlachtga from the mist of time,” proclaims Deborah Snowwolf Conlon, one of the festival’s organizers. It is a contemporary celebration repeated annually, of a piece with countless other seasonal celebrations across the world that have roots both modern and ancient. In this case, neither the choice of site nor date is incidental: The Hill of Ward was one of the main spiritual centers for the ancient Celts, and Samhain was first celebrated at the same time of year millennia ago. New archaeological work is looking closely at the history of the Hill of Ward, which until recently had been overlooked in Ireland’s archaeologically rich Boyne Valley. Researchers are hoping to discover how its use and value evolved over the centuries—along with the traditional rites and celebrations that eventually led to the modern festival of Halloween.

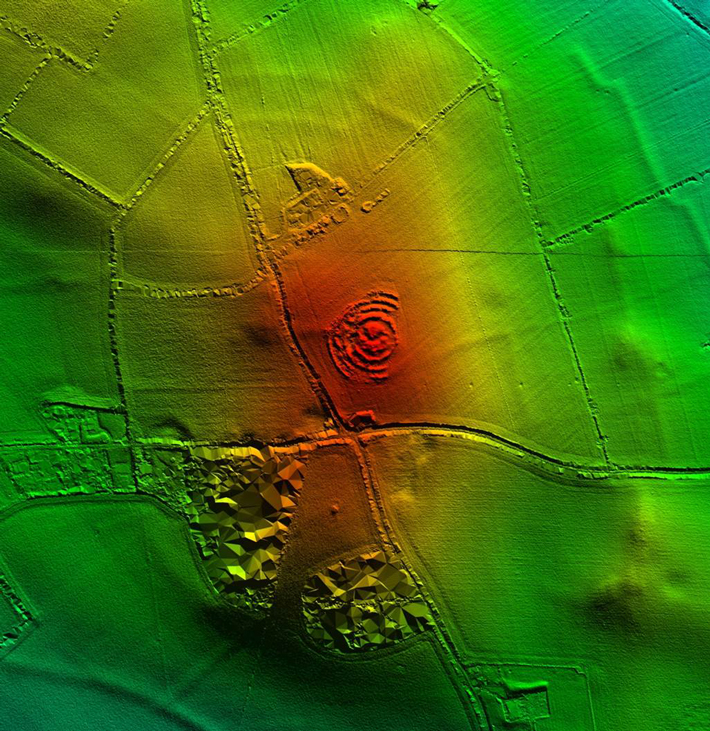

Only 30 miles north of Dublin, the Boyne Valley is the location of one of the world’s most important arrays of prehistoric sites. It includes the well-known “passage tombs” of Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth, which at around 5,500 years old predate even the pyramids of Egypt. The Hill of Tara, the traditional seat of the ancient High Kings of Ireland, is also nearby. Among them sits the relatively modest Hill of Ward, on privately owned farmland, with striking views across the valley. The site today consists of four concentric earthworks that enclose an area roughly 500 feet in diameter, with some of the banks either partially or completely destroyed. Though some archaeological survey work was done at the Hill of Ward in the 1930s, the site was virtually untouched until summer 2014, when a team led by Stephen Davis of University College Dublin began excavations.

Using lidar and geophysical tools, Davis and his team have determined that the Hill of Ward was built in three distinct phases over many centuries. The first phase was constructed during the Bronze Age (1200–800 B.C.), while the last dates to the late Iron Age, around the time of Ireland’s conversion to Christianity (A.D. 400–520). “The middle phase, or physical center, of the monument, which itself was built in multiple stages,” explains Davis, “is proving the most mysterious.” Much of the excavation work done to date at the Hill of Ward has focused on this middle phase, which is providing tantalizing clues into the ritual roles it may have played throughout the centuries.

The importance of the Hill of Ward begins in ancient Celtic mythology with the story of the druidess Tlachtga, the daughter of a sun god named Mug Ruith, who was said to fly in a machine called the roth rámach or “rowing wheel,” that carried the sun across the sky. A version of the legend tells us that Tlachtga was attacked and raped by the three sons of her father’s mentor, a powerful wizard named Simon Magus. Tlachtga then gave birth to three sons, one from each of these three fathers, at the site of the Hill of Ward. According to legend, she died there during childbirth. From then, the hill held her name and the circular earthworks visible today are said to have been built to mark her grave, with one early source stating that a “fortress” had been raised on the site.

Outside the realm of myth, the site gained further importance when it became associated with the Celtic festival of Samhain, the period from sunset on October 31 to sunset on November 1, which marks the beginning of winter and the transition to a new year. The ancient Celts believed that this night marked a critical spiritual transition, when the spirits of all who had died since the previous Oíche Shamhna (“Night of Samhain”) moved on to the next life. Tradition has it that the ancient Celts assembled on Tlachtga on October 31 and built a sacred fire on which sacrifices, perhaps even human, were offered to thank their pagan gods for a successful harvest. On that night, all fires in Ireland are reputed to have been extinguished, and torches lit from the Tlachtga fire were carried to seven other nearby hills to illuminate the surrounding countryside.

“As Tlachtga was known as a goddess of the sun, the Samhain fire ceremonies could have been an attempt to recognize, or even protect, light and warmth against the growing darkness of winter, as well as obviously representing the sun itself,” says Eamonn Kelly, former Keeper of Antiquities at the National Museum of Ireland. According to Kelly, rituals and ceremonies carried out at Samhain offered people the chance to pray for the return of the sun and gave assurance that it would, in fact, come back.

“Likewise, the end of October could also be seen as a time when the natural world is dying. The harvest is finished, plants and trees have died, and livestock have been slaughtered for the winter,” he continues. “Combining these factors together with the disappearing sun, the ancient Celts felt that Samhain was the point in the year in which the world of the living and the spirit world were closest.”

As the Christianization of Ireland began in the early fifth century, the celebration of Samhain began to fade, but not before contributing strongly to the Halloween festivities we know today (see “Night of the Spirits”). “The celebrations are mentioned to us in the early writings of some of the first Christian scholars settling in Ireland, including St. Patrick himself,” says Kelly.

In later centuries, Tlachtga became an important location for other gatherings, including a national assembly of kings and religious leaders in 1167 organized by the last High King of Ireland, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair. “With Samhain traditions slowly dying out, Tlachtga must have still had a strong hold on the imagination,” says Kelly, “with leaders possibly choosing it as a meeting site to symbolically demonstrate power and stability.”

EXPAND

Night of the Spirits

Modern Halloween is a combination of Samhain traditions—many brought to the United States by early Irish and Scottish immigrants—and end-of-harvest practices brought by other European immigrants, with the Christian All Saints’ Day superimposed on it. But Samhain may be its closest ancient relative.

“Halloween is the direct descendant of Samhain and has managed to survive through the centuries in spite of the ‘tacking on’ of All Saints’ Day by those who Christianized Ireland,” says Eamonn Kelly, former Keeper of Antiquities at the National Museum of Ireland. “The spooky stuff that we associate with Halloween, such as ghosts, the dead entering our world, and communing with spirits, can be traced to Samhain, which centuries of Christian tradition never completely managed to stamp out.”

According to Irish mythology, Samhain was a time when doorways to the spirit world were opened, allowing the dead to visit the living world. Some spirits were considered friendly, while others were not, and the Celts created ways to appease them. Food or sacrificial offerings were left outside homes and, in another tradition, revelers visited homes in costumes or disguises and recited poems or verses—all origins of trick-or-treating. Likewise, Celtic druids often offered prophecies on Samhain, not dissimilar to ghost stories told today. An Irish text that dates to the tenth century, Nera and the Dead Man, tells of a man who accepts a dare during a dark and stormy Samhain to tie branches around the body of a hanging dead man. As he does, the dead man suddenly comes to life and asks Nera to carry him on his back. “And of course,” says Kelly, “we have the ever-present Halloween bonfires, following the same exact same type of ritual that could have taken place at the Hill of Ward during Samhain.“

Nevertheless, Tlachtga eventually drifted into quiet obscurity. It came to be known as the Hill of Ward, after a landlord who was evicted from the property by Oliver Cromwell in 1649. Cromwell, who was leading an invasion of Ireland, reportedly used the site as an encampment, which may have resulted in the damage to the earthworks.

Davis and his team began their excavation work at the Hill of Ward in 2014, supported by the Meath County Council, the Irish Office of Public Works, and the Royal Irish Academy. They nearly immediately unearthed evidence of large-scale burning activity—but Davis cautions against connecting the find to Samhain celebrations without further scrutiny.

“Equating the intense burning evidence directly to Samhain fire celebrations is definitely tempting, but difficult to conclusively prove,” he says. “It could be related to metalworking, pottery, or glass manufacturing, which we’ve also found evidence of. However, since these skills effectively transformed everyday materials into new objects, rare enough at the time, they perhaps could have been considered ‘magical.’ Of course this ties in with some of the main Samhain themes.”

Much of the other evidence discovered there does point toward a long history of ritual activity of some sort. For example, large quantities of animal bones—a sign of large-scale feasting—have been found throughout all three phases of the site. The lack of evidence of any residential or day-to-day activity strengthens the idea that it most likely was set aside purely for ritual or celebratory activity.

The excavation has continued with field seasons each year, and there have been finds in all three phases of the site, including some scattered Bronze Age human remains and the skeleton of an infant between seven and ten months old interred much later. The child burial, next to which was a ritual deposit of cow bones, dates to A.D. 450, around the time of the arrival of Christianity. “The child was clearly buried with care and having not found any other evidence of burials on the site,” says Davis, “we’d have to guess that this child belonged to someone significant.” A similar skeleton was previously found nearby at the Hill of Tara, once the royal seat.

Davis and his team suspect that other people may have been buried at the site, and that it might in fact once have been the location of a passage tomb, or a narrow gallery with one or more burial chambers around it. The Boyne Valley has more than 40 such tombs and the Hill of Ward is within sight of several of them, each of which would have required knowledge of architecture, engineering, and even astronomy. All of the passage tombs were built in the Neolithic (4000–2500 B.C.) and represent early examples of ceremonial burials. The earliest phases of the Hill of Ward site date to the later Bronze Age, but Neolithic finds there, including two stone axes, two small pieces of pottery, and a javelin head, suggest that deeper, stony layers could contain an even older phase of use. “It is easy to imagine that an early passage tomb is indeed here,” says Davis, “and that the location continued to be a focus for ceremonies after the tomb was either abandoned or collapsed, or was simply incorporated into a later phase.”

The possibility of a passage tomb presents another intriguing idea that could connect the site’s earliest stages with Samhain. Several such tombs near the Hill of Ward are aligned with seasonal equinoxes or the Celtic quarter days that fall between them, one of which is Samhain. For example, Newgrange is famous for the illumination of its passage and inner chamber by the winter solstice sun on December 21, while the Hill of Tara is closely associated with the March 21 spring equinox—and a passage tomb at that site is reputed to be aligned with the Samhain sunrise.

“As the Celtic New Year began with Samhain, there is a correlation between the year starting with winter, with the sun near its lowest point, and working toward light and longer days as the year continues,” says Kelly. “As we know, the Celts were obsessed with the sun. It wouldn’t surprise us at all that if an actual entrance were discovered at the Hill of Ward, it would be solar-aligned to an autumn solstice sun, similar to what we see at Newgrange.”

The most recent revival of Samhain celebrations at the Hill of Ward began 19 years ago. The festivities have been gaining in popularity and demonstrate that, for varying reasons, the Hill of Ward is one of those sites that seems to lend itself to contemplation of the landscape and to the celebrations that have long been a part of human culture.

“It is a fascinating site to visit and reveals the types of rituals and ceremonies that have been held here over the centuries, and how they may have changed along the way,” says Davis. “This smaller hill has managed to influence one of our most beloved holidays, not only in Ireland, but around the world.”