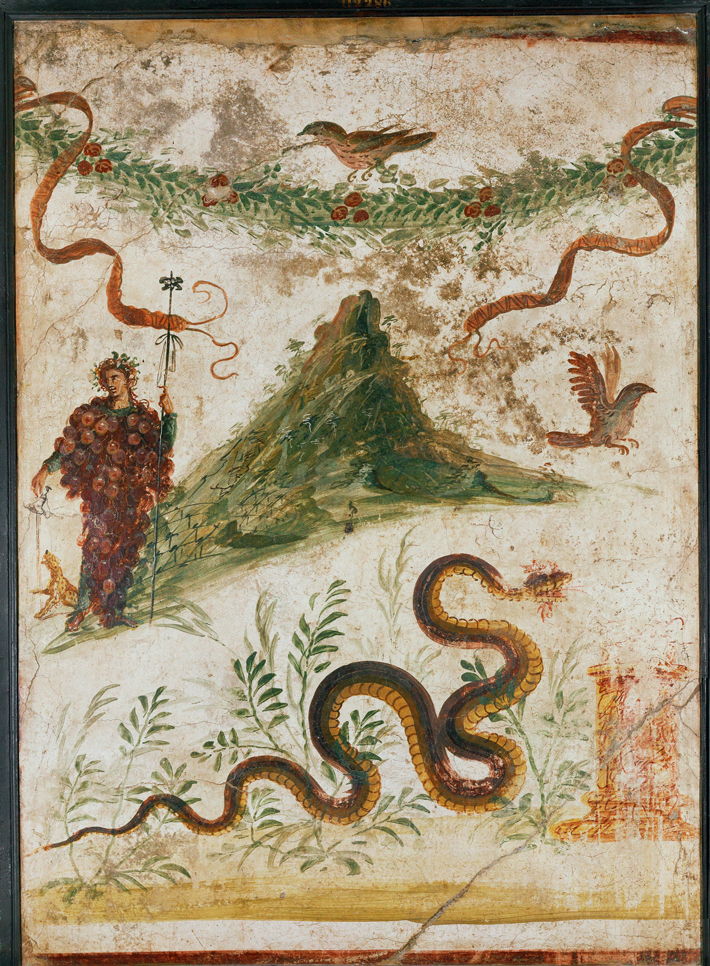

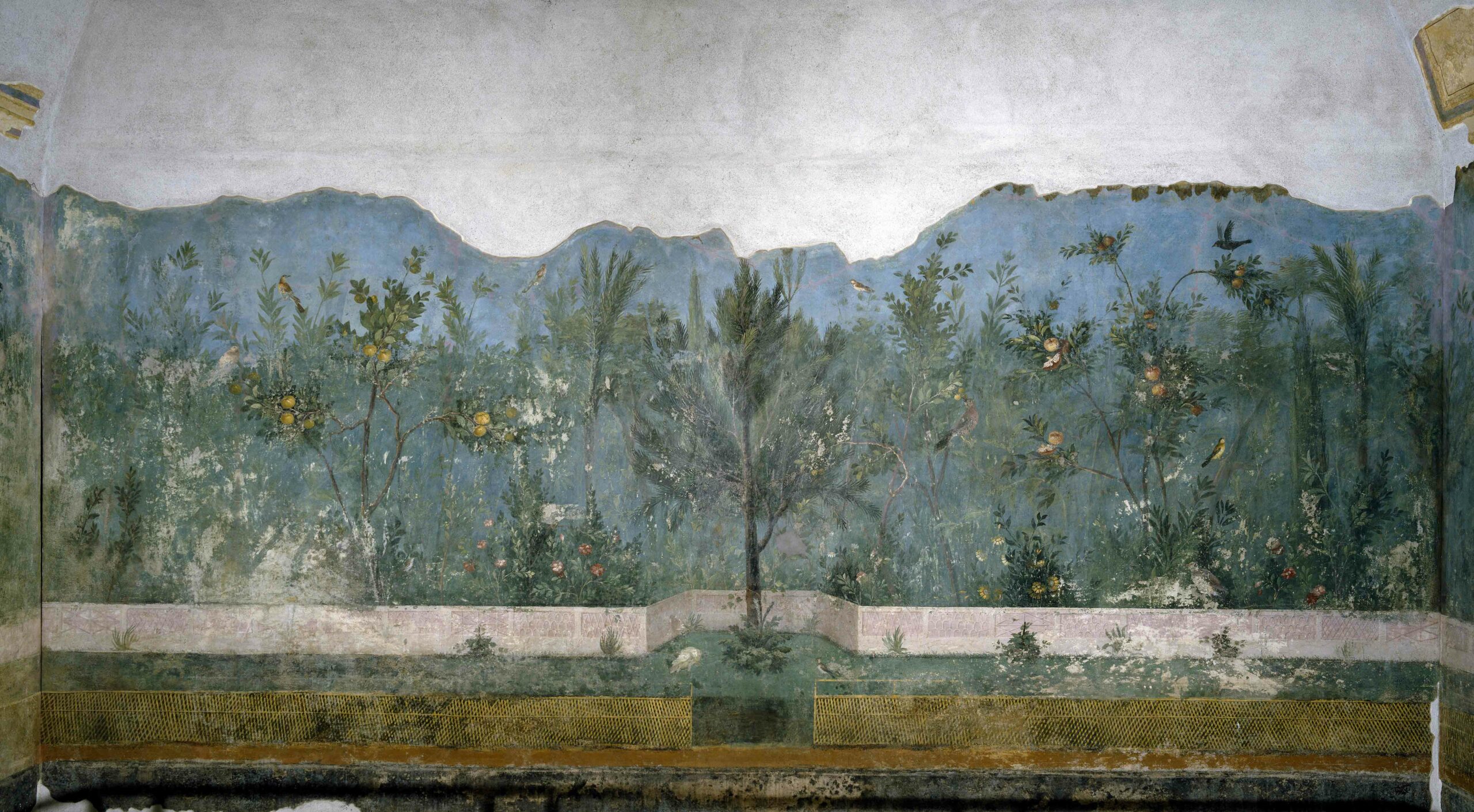

Evidence continues to reveal much about the quality of life of the residents of ancient Pompeii. The city created an intricate and robust system for the local production of food and wine. Researchers have long been aware of frescoes, found in many surviving houses and villas, depicting plants and the pleasure of eating and drinking. Remains of triclinia, or dining rooms, and of food stalls, bakeries, and shops selling the fish sauce garum are abundant.

Garden archaeology as a discipline was pioneered in Pompeii in the 1950s when archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski began to excavate areas between the remaining structures. She discovered that homeowners planted flowers, dietary staples, and even small vineyards. “From the oldest type of domestic vegetable garden, the hortus, to ornate temple gardens,” explains Betty Jo Mayeske, director of the Pompeii Food and Wine Project, “you see evidence of cultivation in nearly every available space in Pompeii.” It appears that both grain and grapes were grown in small, local contexts. “There was a bakery on practically every single corner and the mills were there too, as well as a counter room and large ovens,” she says. “The whole production process took place there, and there are also several similar examples of small-scale vineyards.” One of Jashemski’s innovations was to apply the practice of making molds of the dead, known since the 1860s, to making molds of individual plants. “Casting had been done in cement and plaster on human remains for years,” Mayeske says, “but Jashemski used that technology to cast the plants’ roots, which helped definitively identify all of these gardens and vineyards.”