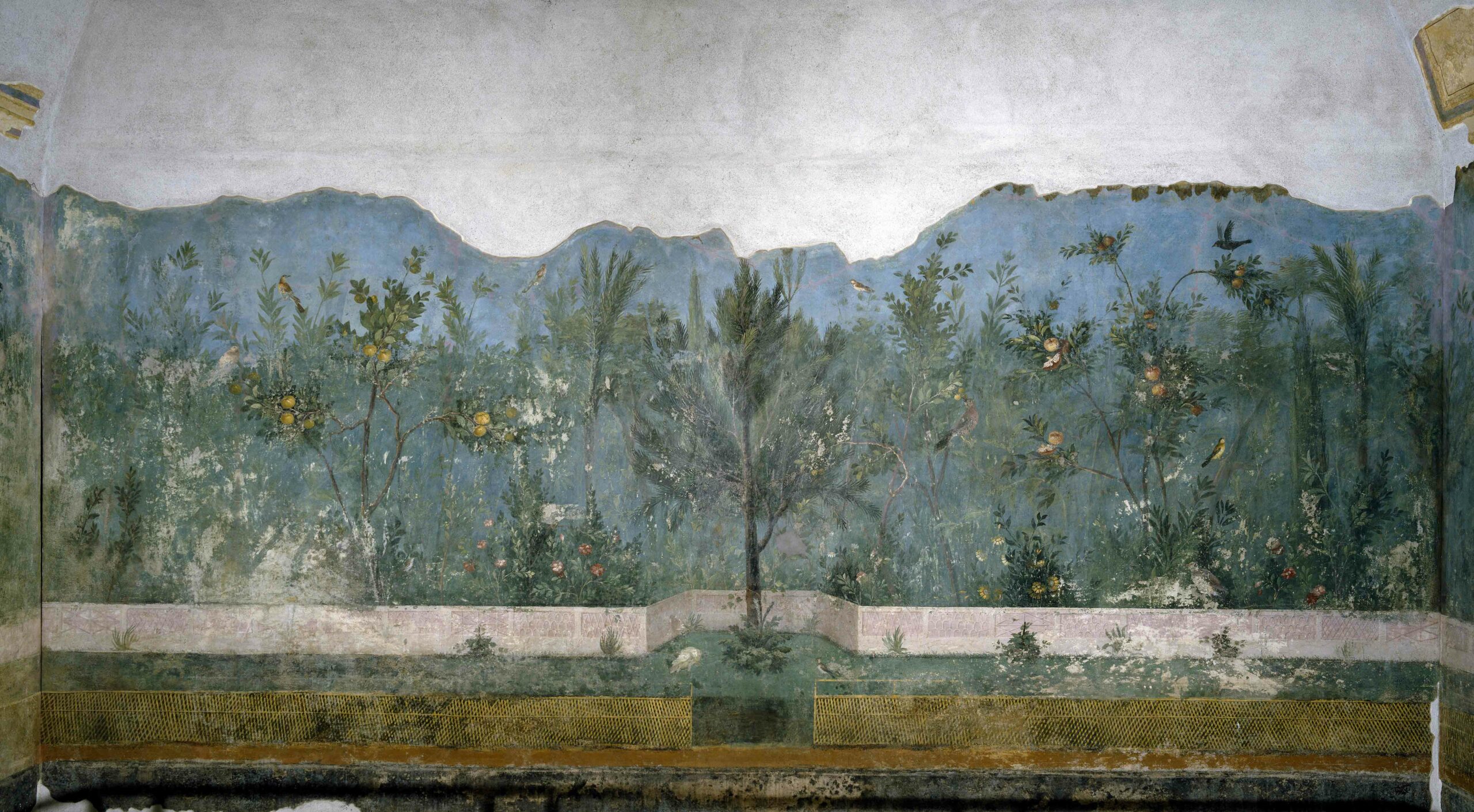

Beginning in the second century b.c., Rome’s most prominent families began to build luxurious country estates for which exquisitely designed gardens were essential. The Bay of Naples, with its sweeping vistas and cool breezes, became one of the most popular destinations. Today, the coastline is littered with the ruins of large villas and their opulent gardens, buried and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. According to Cornell University’s Kathryn Gleason, it is only recently that archaeologists have truly begun to understand the complexity and various functions of a villa garden. “A design might have been initiated as a display of wealth, but also might provide simple pleasures, such as shade, produce, a place for children to play, for weary politicians to find retreat, or for young people to make love,” she says.

Two of the best-preserved gardens are found at the Villa of Poppaea and the Villa Arianna, located at Oplontis and Stabiae, respectively. These grand spaces contained porticoes, footpaths, fountains, and a variety of trees. In recent decades, excavations in both places have also revealed the remains of planting beds, tree root cavities, carbonized plant parts, and even in situ planting pots. “These features allow us to understand the design and layout, and thus much about the experience of the garden,” says Gleason, “which is something that only archaeology permits in a fully spatial sense.” To learn more, go to Gardens of the Roman Empire, the website of a project that collects information on gardens throughout the empire.