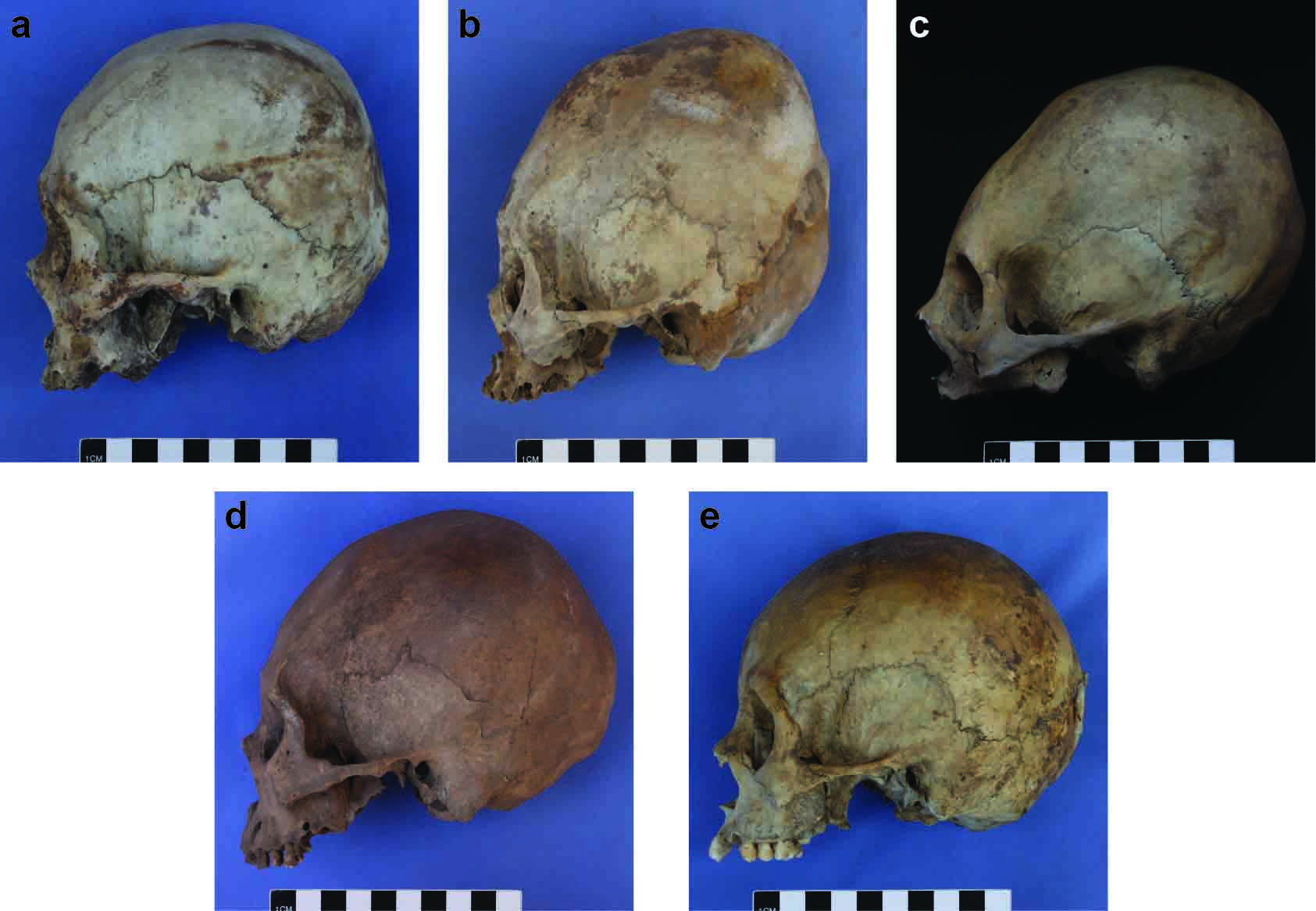

The Collagua, who lived in the upper reaches of southern Peru’s Colca Valley, were described by sixteenth-century Spanish conquerors as shaping their heads into a distinctive, elongated form. A new study led by Matthew Velasco of Cornell University finds that these head-modification practices changed dramatically in the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish.

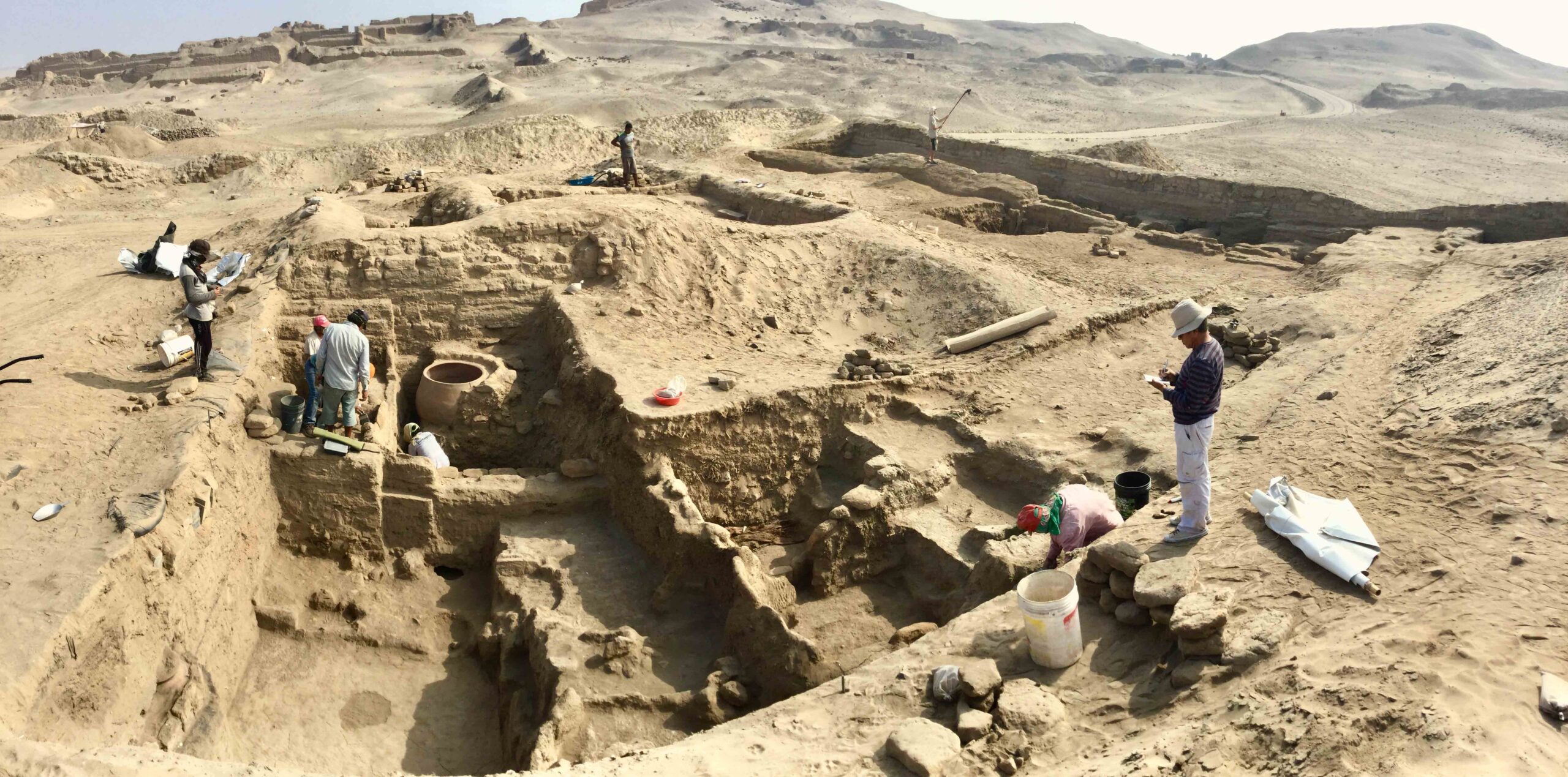

The team looked at 213 skulls from two elite Collagua burial sites and found that the rate of modification increased greatly over time—from 39.2 percent of skulls from 1150 to 1300, to 73.7 percent from 1300 to 1450. Greater diversity of modification styles was found in the early period, whereas the long, slender shape noted by the Spanish became dominant in the later period, with 64.3 percent of the modified heads hewing to this style. It is unclear why the elite Collagua converged on this style of head modification, but Velasco suggests it may have had to do with a need to develop a group identity—perhaps to contrast with the Inca, who took over the area in the fifteenth century. “There were likely to have been social pressures,” he says, “possibly in the context of war or encroachment by outsiders, that led to a firmer definition of regional identity.”