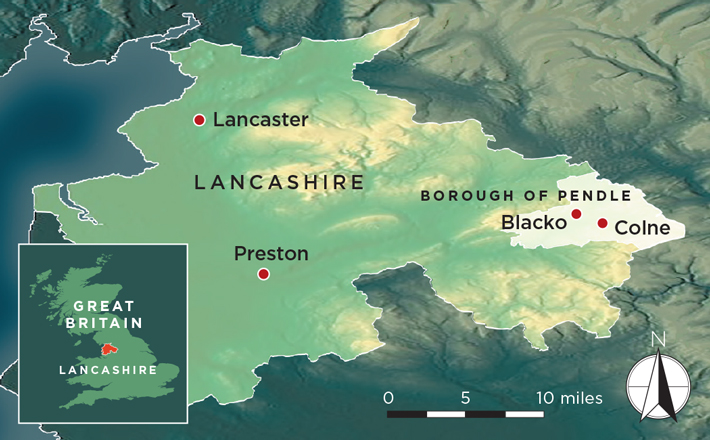

In the fields belonging to Malkin Tower Farm, outside the village of Blacko, in Lancashire’s borough of Pendle, stands a solitary tree where small charms, fruit, and even the odd dream catcher are known to appear. These offerings are left behind by amblers on countryside strolls who are aware of the farm’s association with the notorious Pendle witch trials. In 1612, nearly a dozen people from this scenic region of hilly pastureland were accused of witchcraft, convicted, and hanged in the nearby city of Lancaster. Though they took place more than 400 years ago—nearly a century before the better-known witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts—the trials continue to captivate an eclectic mix of scholars, tourists, and neo-pagans. Researchers now conducting excavations at Malkin Tower Farm are hoping to find archaeological evidence of the witches themselves. The task is a daunting one, since material remains of magical practice are often ephemeral and difficult to distinguish from everyday objects. It also requires an understanding of the Lancashire in which the condemned lived, which was beset by religious and social upheaval, as well as substantial changes in traditional modes of rural life.

The team, led by archaeologist Charles Orser of Ontario’s Western University, chose to investigate Malkin Tower Farm because it shares the name of a property where the family most closely associated with the trials, the Devices, are known to have lived. The location Orser selected is only one of the possible locations for their home. No standing buildings from the seventeenth century—and no tower—survive at the site, and the exact location of the Device family home was never recorded. But in this part of the world, where farms are handed down over generations, place-names persist. “The names of individual fields, in particular, can be very ancient in this area,” says Malkin Tower Farm owner Andrew Turner, who, with his wife Rachel, operates holiday accommodations at the property. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the name ‘Malkin’ is actually quite a bit older than the 1612 trials.”

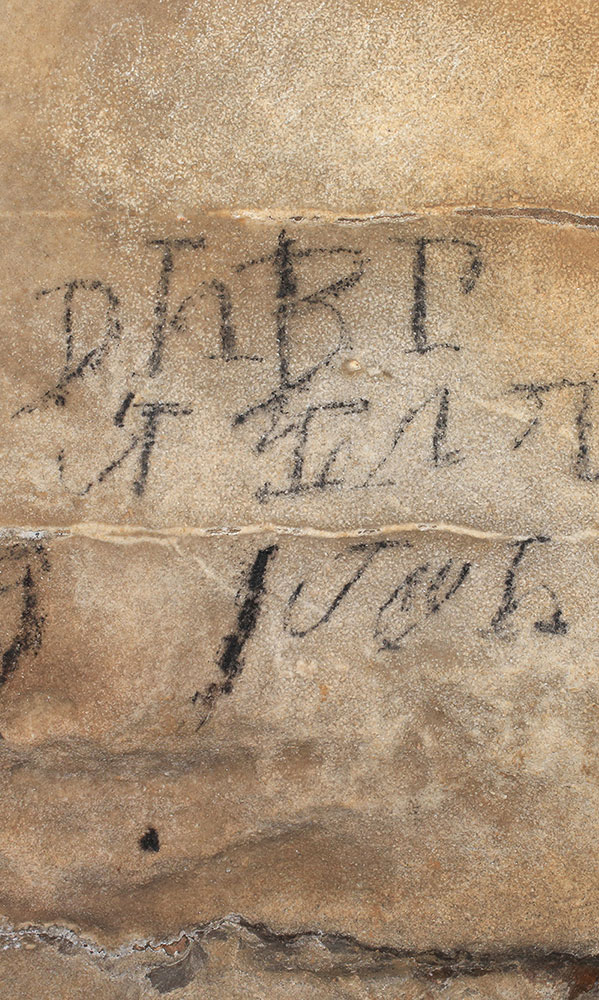

The farm’s current cottages, which sit on the lower slopes of a hill and look out over a vista of pastures, stone walls, and small lakes, date to the eighteenth century. Orser chose to investigate a field directly behind them, hoping to find evidence of earlier buildings. A 2018 field season based on geophysical surveys didn’t turn up much, but the team has now encountered what Orser says are the remnants of a demolished residence. “Clearly where we’re excavating now is a tumbled house, there’s no question about it,” he says. “And I can imagine that the local authorities would have wanted to demolish a house that they believed was associated with evil.”

The story of how Malkin Tower came to be associated with the devil’s work is recorded in a 1613 volume entitled The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster. The history was written by Thomas Potts, a clerk at the Lancaster Assizes, the court where the Pendle witches were charged and condemned. The narrative, whose bias toward the prosecution is clear, describes the events as follows: On the 21st of March 1612, a young woman named Alizon Device was begging on the road leading to the village of Colne when she met a traveling peddler named John Law. She asked Law for some metal pins. He declined and, shortly after his refusal, suffered a collapse of a sort that would now likely be diagnosed as a stroke. Law recovered well enough to make it to the local inn, or to a house nearby, where he told of his encounter. He claimed that, before his collapse, the young woman had cursed him. Deciding to take the case to the authorities, Law and his family contacted the local justice of the peace, Roger Nowell, who took statements from Alizon; her mother, Elizabeth Device; her brother, James Device; and Law’s son, Abraham. The initial examination must have piqued Nowell’s curiosity. Seeking other local reports of witchcraft, he questioned Alizon’s grandmother Elizabeth Southerns—who was in her 80s, blind, and known in the community as “Old Demdike”—as well as another octogenarian, Annie Whittle, nicknamed “Old Chattox.”

By April 4, according to Potts’ history, Nowell had heard enough. He committed Alizon Device, Old Demdike, Old Chattox, and Old Chattox’s daughter, Anne Redferne, to prison in Lancaster Castle to await trial. Fears of a witch conspiracy came to a head when reports reached Nowell that, on April 10, fellow witches and friends of the Devices and Old Chattox attended a meeting at Malkin Tower. There, they were said to have plotted a prison break, discussed spells and hexes to cast against the authorities, and planned to blow up Lancaster Castle. Nowell extracted confessions to the effect that the meeting was not a one-off, but rather a regular witches’ “sabbath” held at Malkin Tower. He then arrested several more people on suspicion of participation. The accused were alleged to have used forms of malevolent magic to curse humans and animals to cause them disfigurement or death, to have created clay effigies representing victims, and to have cultivated supernatural entities, called “familiars,” that were said to appear in the guise of animals, to do their evil bidding. The trials were held on August 18 and 19, 1612, by which time Old Demdike had died in jail. In the end, Alizon, Elizabeth, and James Device, Old Chattox, and six others were found guilty and executed.

Documentary evidence of the Device family essentially disappears after the executions, even though the youngest member, a small girl named Jennet, survived the trials. Jennet was probably around seven or eight at the time and is thought to have been forced to give evidence against her sister, brother, mother, and grandmother, a rare example of a young child’s testimony being admitted in an English trial. It entered common law as a precedent that is still studied by legal scholars today.

Once Orser had identified archaeological evidence of a domestic dwelling, his next task was to determine what artifacts might possibly be related to magic. “One of the problems is that you are often really just looking for mundane, quotidian objects,” he says. “You might be lucky and find, say, a specific type of German stoneware jug made during the period called a bellarmine, which was used as a protection device against witchcraft. Or you might find the pins sometimes put in those bottles, such as the kind Alizon Device supposedly asked John Law for.” More often, though, he explains, archaeologists look for artifacts arranged in certain ways, or objects that have marks on them that might be symbolic.

Amid the ruins of the house at Malkin Tower Farm, the team has unearthed what they believe is a hearth area and, in the same vicinity, a mostly intact pipe bowl. Orser hopes the bowl will soon be confirmed by specialists to date to the early part of the seventeenth century, the very time that the Device family may have been living there. The researchers have also discovered a substantial assemblage of coarse earthenware vessels that would have been used for serving food and drink, as well as for collecting and storing milk. Many of these fragments appear to date from the same period as the pipe. While nothing Orser can point to as being overtly magical has yet been found, some intriguing possibilities have begun to emerge. “In addition to the well-preserved pipe bowl, we found a piece of ceramic that is almost mirror-like,” Orser says. “If you’re familiar with scrying, a practice of looking into a surface to get visions, that’s what this will make you think of.” For reasons still debated by scientists, many people report hallucinations upon staring into a mirror, or a similarly reflective surface, for an extended period. “This fragment could be the right age, and I’ve never seen anything like it,” Orser says. “It practically reflects.”

In Potts’ account of the trials, he makes much of the allegation that Old Demdike and the rest of the Device family created effigies, called “pictures,” out of clay, which they used to manipulate and cause pain to their victims. On the west side of the house, Orser’s team has uncovered a number of nuggets of pure clay. “There were hunks of something like modeling clay that were clearly distinct from natural clay deposits,” Orser says. “It was very unusual in terms of the surrounding soil.”

The large volume of coarse earthenware Orser has recovered may be a result of the site’s use as a dumping ground following the demolition of the house. The number of later eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ceramics indicates the former homestead may have been a trash heap for at least 100 years after the building was razed. “We just can’t figure out exactly where all of this stuff could have come from,” Orser says. “There’s a tavern nearby, which may have been contemporaneous with the 1612 trials, but it’s a long way to bring your trash.” He suggests the placement of the dump might be due to lingering negativity in the minds of local people, even generations removed, resulting from the witch trials. To Orser’s surprise, one excavation layer contained a nearly intact, handblown glass bottle, for which he now hopes to obtain a date.

To look out from Malkin Tower Farm today is to survey a landscape of neatly divided fields that has not changed substantially in almost 400 years. The last time it did, Old Demdike was alive to see it. The latter part of the sixteenth century was a tumultuous period in the Pendle area. Common lands were rapidly being converted into private pastures, a policy called “enclosure” that began in the late Middle Ages and was widespread across Britain by 1612. Many people in Lancashire also provoked the ire of both the Crown and the Church of England for their stubborn refusal to abandon Catholicism.

Local Pendle historian John Clayton has spent years consulting property deeds, legal documents, and municipal records held in the Lancashire Archives. He says that the social, religious, and economic environment of the time may have created an atmosphere conducive to a witch hunt. “There was currency inflation throughout the 1500s, as well as a series of weather-related crises in the agricultural system,” Clayton says. A 1507 law had given local landowners the opportunity to acquire land in Pendle on lifetime leases. The tenants who managed to acquire newly enclosed lands immediately became the haves, while smallholders and those living on the margins became the have-nots. A century later, in 1607, King James I (r. 1603–1625) added fuel to the fire by decreeing existing leases invalid, provoking a scramble on the part of landowners to legally repurchase their property. “This meant that only the wealthiest landowners had the opportunity to officially take on their land,” Clayton says. “and that they also had the opportunity to take on the land of their poorer neighbors.”

Clayton is among those who do not think that the current Malkin Tower Farm is associated with the Device family. Based in part on place-names referenced in the law clerk Potts’ account, he is beginning to explore an alternative site a few miles away. He suggests the owners who built the current Malkin Tower Farm in the eighteenth century may have appropriated the Malkin Tower name, perhaps because of a similarly named field already existing at the property. Clayton and Orser do agree, however, that archaeologists should be looking for a dwelling that was probably demolished and subsumed by a larger estate. “It’s possible Demdike was on a holding her family had held for a generation or two,” Clayton says. When they couldn’t afford to pay the extra money to buy the land after James I canceled all leases, he suggests, it may be that another family took over the land and allowed the Devices to stay in the building, which was called Malkin Tower.

Clayton points out that other communities across England faced similar tensions over property ownership at the time, and thus resentment over access to land resources is not enough to explain accusations of witchcraft. Additionally, while tens of thousands of people are estimated to have been executed in continental Europe during witch persecutions from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries, in England that number appears to have reached only into the hundreds. That witch scares were relatively uncommon in England raises the question of what specific circumstances might have been to blame in Pendle and for other witch hunts that occurred intermittently over the seventeenth century.

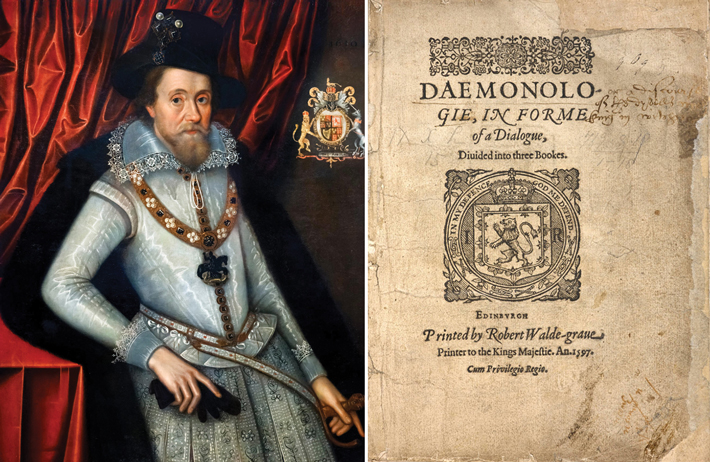

Part of the answer lies in the personal beliefs of and laws passed by James I, who, in 1590 (when he was King James VI of Scotland, but not yet king of England) attended witch trials in North Berwick, East Lothian. In 1597, he published Daemonologie, a treatise on various forms of black magic. In ensuing years, the monarch became obsessed, for a time, with stamping out witchcraft, during a period that coincided with the Church of England’s general policy of repressing English Catholics, a large community of whom lived in Lancashire. “Possibly the whole 1612 trials, and surely the Potts account of them, were specifically designed with James I in mind, to show support for his views and to curry favor at court,” says Orser. Government and church officials had only to find a way to conflate what they considered heresy with witchcraft. “These families living on the fringes in rural Lancashire were hanging on to Catholicism. They may not have even been doing it as a protest but just because it was the way things were,” Orser says. “In some instances, what are referred to as ‘spells’ are pieces of old Latin prayers.”

Another explanation for the Pendle witch trials may lie in forgotten folk practices that often go unmentioned in official historical documents. Seventeenth-century Britons were mostly illiterate, lived by the rhythm of the agricultural calendar, and fought illness without the assistance of modern medicine. For decades, many historians subscribed to the notion that as Christianity replaced indigenous pagan religious systems in the British Isles from the late Roman period onward, magical superstition died out. Archaeologists, however, do find objects, markings, inscriptions, and other evidence of rituals and practices that should, they say, be considered magical. “When people start talking about magical invocations, they rarely try to define magic,” says archaeologist Christopher Fennell of the University of Illinois. “One definition of magic is that it is any kind of personal supplication from a once-dominant religious system which got pushed off center stage by a new system.” Christianity, Fennell says, by way of example, marginalized paganism in England, but individual rituals surviving from those belief systems continued to be carried on in private spaces. “The problem for archaeologists,” Fennell says, “is when it’s private and for personal reasons, you have tremendous opportunity for variation, and it’s hard to know what to expect.”

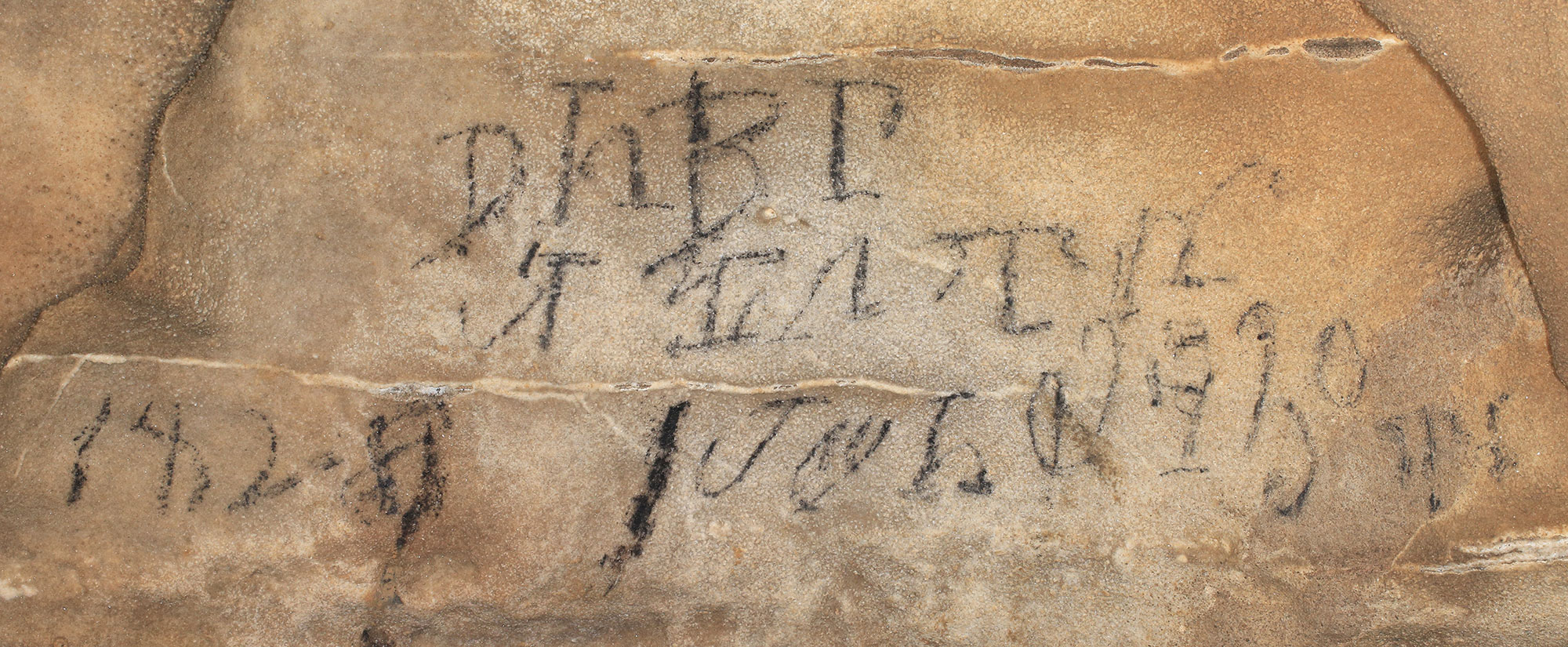

Adding to the difficulty for Orser and his team is that the overwhelming majority of magical evidence is found in surviving buildings and not in the ground. “If you’re excavating in a house, or doing a preservation survey, you’re more likely to find something,” Orser says. Commonly documented practices in England include the deliberate caching of shoes in walls, or the etching of markings of three—an allusion to the Holy Trinity—into fireplace mantels to ward off accidental blazes. “There’s a chance you could find something like that in the soil, like a cat skeleton or horse head buried under the threshold of a building,” Orser says. “But otherwise, how can one tell certain mundane objects from other mundane objects that were used in magical or spiritual ways?”

It is impossible to know just how effective people thought these practices were, but their neighbors clearly believed that Old Demdike and Old Chattox had some kind of power, as they both made their living traveling from farm to farm to heal sick livestock. “Farmers didn’t necessarily understand why their cattle were ill, and believed these women had the ability to cure them,” Orser says. “The other side of that coin, of course, is that if you can cure, you can curse, too.” A sudden outbreak of disease in a community or a spate of personal misfortune could easily be blamed on such a healer, known in the parlance of the time as a “cunning woman.” There needn’t even have been any evidence of malevolent intent, Fennell says, for such traditional folkways—even if they were widely accepted in the community—to be recast as evil. “You have people who are practicing folk religion without concerning themselves with Christian concepts of Satanism or diabolism,” he says, “but they’re in danger if they’re practicing their own folk religion at a time when tensions arise within their community.” All that may have been required for any folk magic practices the Device family was engaged in to be misconstrued as witchcraft was for an authority figure, such as justice of the peace Nowell, to become involved. “Beginning in the late 1500s,” Fennell explains, “both ecclesiastical and civil authorities completely reconceptualize everything and persecute anyone they find problematic, often elderly women who weren’t necessarily thinking about going against Christianity, but were engaging in traditional practices intended to manipulate spiritual forces, whether to protect or to harm.”

Determining whether a family of witches lived at Malkin Tower Farm will require a careful cataloging of the hundreds of objects Orser and his team have recovered from the hillside. Even when this work is complete, arriving at a definite conclusion may never be possible. And who is to say that even if some incontrovertibly magical artifact were to appear in the ground, another such object wouldn’t also appear at the next farm over, and the next, and the next after that.