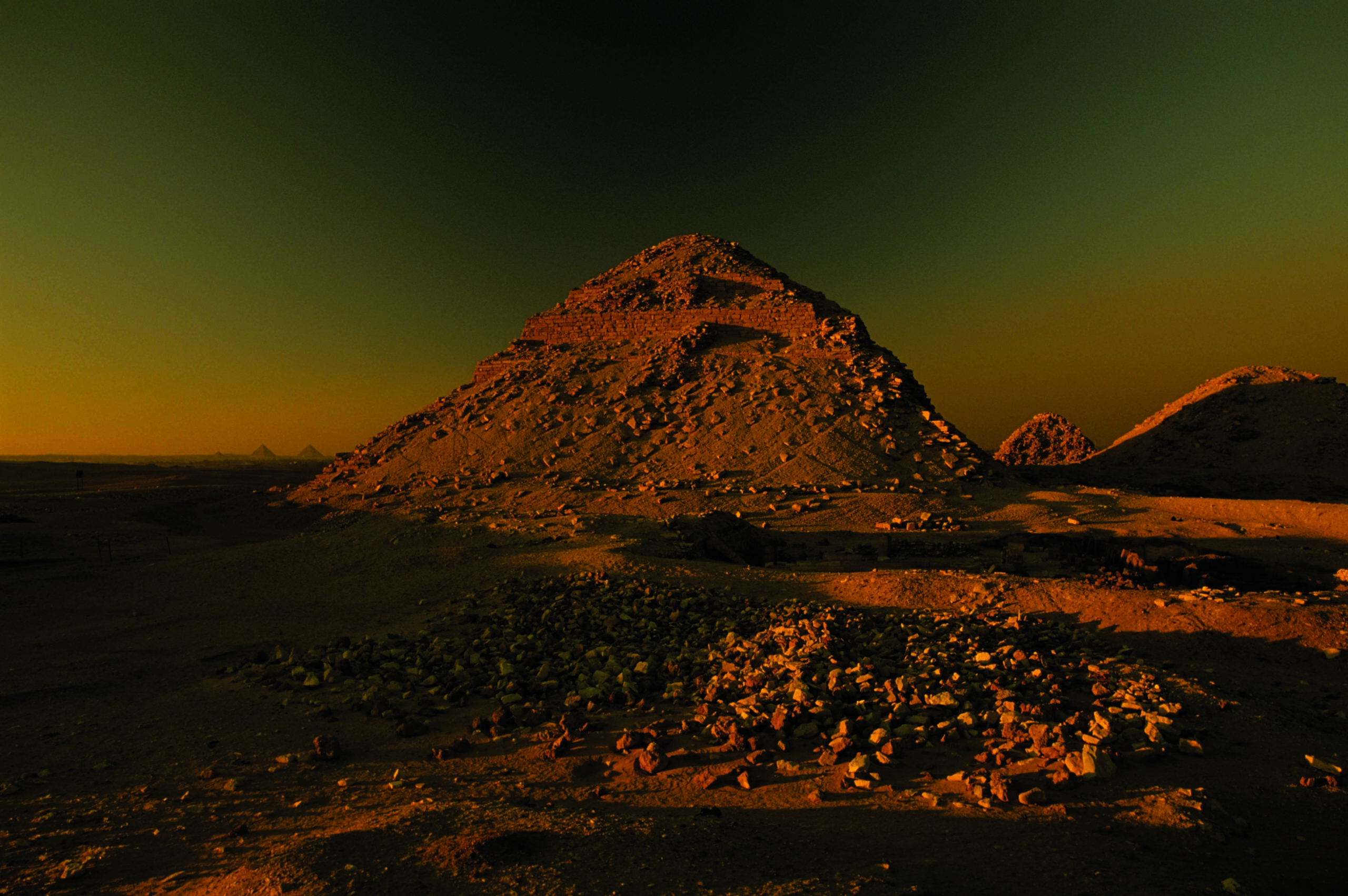

Not far from the foot of Mount Carmel and the industrial port city of Haifa on Israel’s Mediterranean coast sits a grassy mound dotted with ruins of buildings and walls, the accumulation of more than three millennia of settlement. From the top of the mound, or tel, a view of the sea stretches out. Birds and fishermen perch on the numerous rocks that dot the shallow water, which is navigable only by the smallest of boats. Since the first excavations in the 1960s, archaeologists have found the site, called Tel Shikmona in Hebrew, or Tell es Samak, “Hill of the Fish,” in Arabic, curious. They couldn’t understand why, beginning in the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1200 B.C.), through the Iron Age (ca. 1200–550 B.C.), and continuing more than 1,000 years into the Byzantine period, people would settle somewhere with such a rocky, shallow coastline and no harbor, a place where farming and trade would have been difficult. But now, 50 years later, archaeologists examining artifacts from Tel Shikmona stored in a local museum have determined that its residents used the location to their advantage in an entirely different, and very lucrative, way.

Among the stored artifacts and original handwritten documents from digs at Tel Shikmona in the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists Golan Shalvi and Ayelet Gilboa, both of the University of Haifa, have found dozens of pottery vessels and sherds covered with purple and blue stains, evidence that people were producing a coveted dye using liquid extracted from the glands of murex sea snails at the site. Until now, such evidence from the Bronze and Iron Ages has been limited to scattered pieces of stained pottery and heaps of murex snail shells found at several sites in modern-day Lebanon and Israel.

In the ancient world, textiles colored with this dye were worth their weight in gold and were often listed along with precious metals in trade and tax records. These textiles bestowed prestige, royal status, and even sacredness on those who wore or were buried in them. The dye is referenced in the Hebrew Bible, in which its purple and blue colors are called argaman and tekhelet, respectively, and instructions are given to hang strings dyed in the tekhelet shade from the corners of garments. In the twelfth century B.C., according to contemporaneous administrative documents, the kingdom of Ugarit in northern Syria paid tribute to the occupying Hittites in the form of purple wool. A ninth-century B.C. inscription attributed to the Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III records that he received purple wool as an incentive to form an alliance with the seafaring traders known as the Phoenicians. Purple wool is also listed among the war spoils taken by Tiglath-Pileser, the Neo-Assyrian king who conquered ancient Syria and Palestine in the eighth century B.C. Much later in history, the dye was responsible for the distinctive purple togas worn by high officials of the Roman Empire. “We are talking about one of the most important industries in the Iron Age and across the ancient world,” says Shalvi. “Now we finally know what would bring people to such a place.”

Shalvi is part of an interdisciplinary project led by Gilboa. They are attempting to better understand the cultural identities, economic activities, and trade relations of the people who lived at Tel Shikmona during the Iron Age. The site was first excavated by Israeli archaeologist Joseph Elgavish in the 1960s. Amid its ruins, which include Iron Age buildings, defensive walls, and olive presses, as well as remains from the sixth through fourth centuries B.C. and from later periods, too, Elgavish collected thousands of artifacts. These include the stained pottery, weaving and spinning equipment, carved figurines, and hundreds of storage vessels. He portrayed the site as a residential Israelite city that flourished in the tenth century B.C. After sorting through the artifacts and documents, however, Shalvi and Gilboa view it differently, seeing Tel Shikmona not as a city but as an industrial site focused on the dye industry, especially between the tenth and sixth centuries B.C. Further, they believe that defining the site as exclusively Israelite does not reflect the region’s complexity. Some archaeological layers also contain evidence of the Phoenicians, whose coastal territories lay to the north of the Israelites’ settlements.

Shalvi and Gilboa believe their research may help track regional power shifts in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., a tumultuous time during which the fearsome Neo-Assyrian Empire expanded from its base in Mesopotamia. While the Israelites fell to this new power, the Phoenicians maintained some control over their cities, colonies, trade routes, and territories, likely including Tel Shikmona. The dye industry there would have given them—or anyone else—access to a highly desirable commodity. “You can’t understand the region without understanding Tel Shikmona,” says Gilboa. “Controlling this site would have meant economic and political power.”

Meanwhile, another team from the University of Haifa, led by archaeologist Michael Eisenberg, is investigating the Roman and Byzantine areas of the site. There, over the years, archaeologists have uncovered villas, churches, and mosaics dating to the third to fifth century A.D. More recently, they have unearthed industrial pools and murex shells, tantalizing evidence that the dye industry may have been resurrected to produce brilliantly colored textiles to feed the appetite of yet another powerful empire.

Shades of purple and blue are abundant in the sea and sky of the Levant, but were uncommon in the clothing, jewelry, and art of the ancient world. “Blue is incredibly rare,” says Baruch Sterman, a physicist and cofounder of Ptil Tekhelet (“A Blue Thread”), an Israeli organization that studies and produces murex dye for modern Jewish religious garments. He explains that, in order to appear blue to the human eye, an object must absorb red light, something few naturally occurring materials do. Among the handful of blue materials available in antiquity were stones, including lapis lazuli from what is now Afghanistan, and plants such as indigo, which grows in warm climates like India and Africa, and woad, which grows around the Mediterranean. Ground-up lapis lazuli can be used to make paint, but not to dye textiles. And, while indigo and woad can color fabric, they eventually fade. Part of what made murex dye so valuable was that its colors remain brilliant. For example, 2,000-year-old pieces of murex-dyed wool found in caves near the Dead Sea are still vibrant today.

Some aspects of the dye-making process remain unknown, but it involved breaking open sea snail shells, removing the hypobranchial gland, and harvesting the clear fluid inside. In a process taking several days, this liquid was then heated and dissolved in an alkaline solution believed to have been made from urine or certain plants. This eventually produced a yellow fluid, into which yarn was dipped. Upon being exposed to light or oxygen, the yarn turned a rich hue. At least three species of murex sea snails produce the color-changing liquid, and the dye’s final shade depends on the species used, the length of exposure to the elements, and the type of fabric. “It’s more of an art than a science,” says Julie Mendelsohn, a textile expert at the University of Haifa who works on materials found at Tel Shikmona. It takes thousands of snails to produce just a small amount of the dye, and the Talmud, as well as Greek and Roman historians, describe the dye-making process as messy, malodorous, and tedious. “The small fish are crushed alive, together with the shells, upon which they eject this secretion,” Pliny the Elder writes in his first-century A.D. Natural History. “The smell of it is offensive.”

For more than 2,000 years, historical sources have credited the discovery of this process to the Phoenicians, who, starting around 1500 B.C., settled a stretch of the Mediterranean coast in present-day Lebanon, Israel, and Gaza. They founded city-states such as Tyre, controlled key trade and shipping routes throughout the region, and established numerous colonies in places including Cadiz in modern Spain and Kition on Cyprus. According to a second-century A.D. account from the Greek historian Julius Pollux, a dog belonging to the Phoenician king Heracles of Tyre accidentally discovered the dye’s source by biting on a seashell. In fact, the word “Phoenician,” a moniker first bestowed by the Greeks, means purple.

Despite the long-standing association between the Phoenicians and murex dye, however, scholars believe they probably were not the first to develop it. Instead, evidence increasingly points to the island of Crete as its origin. There, from about 3000 B.C. until the mid-fifteenth century B.C., the Minoans established extensive maritime trade networks around the Aegean. Ancient tablets from the Minoan palace at Knossos refer to the royal use of purple textiles. And, in 2016, chemical analysis of residue in stone vats and vessels from a Minoan-era dye installation on the nearby island of Pefka identified biomarkers of murex snails, along with lanolin, which was used to prepare raw wool for dyeing. This indicates that as far back as 1800 B.C.—at least 300 years before the rise of the Phoenicians—people there colored textiles using murex dye. Andrew Koh, an archaeologist and historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who conducted residue analysis of pottery and stone dyeing installations from Pefka, says the rugged shorelines of Crete and nearby islands were especially suitable for murex snails, which thrive along shallow, rocky coastlines. “In terms of pure numbers [of snails] and ecological conditions,” he says, “chances are this industry was invented in Greece.”

Other cultures, including the Phoenicians, eventually learned of the murex dyeing technique through trade relations, Koh suggests, and he and Gilboa agree that the Phoenicians likely improved on the Minoans’ techniques and expanded the dye’s reach. Says Koh, “It’s clear that by the eighth century, the Phoenicians have the hold on this industry.”

In the 1960s, when Elgavish began exploring Tel Shikmona, he uncovered evidence of habitation going back to the Bronze Age. But in his limited publications, he focused mostly on his discovery of the four-room house and olive presses, which he identified as typical of tenth-century B.C. settlements belonging to the ancient Israelites. He did mention finding a few scattered pieces of Phoenician pottery and vessels common in Cyprus, but said nothing further about them. Most of the finds were then stored at the nearby National Maritime Museum.

In 2016, Shalvi and Gilboa began to study these finds. They uncovered substantial evidence of a Phoenician presence at Tel Shikmona, including figurines and pottery, and enough purple-stained sherds to determine that it had been a major murex dyeing installation at various times between the tenth and seventh centuries B.C. A few of the sherds had been tested for murex in the 1990s, but until the current project, the extent of the collection was unknown. “It was the volume of purple sherds that was surprising,” Shalvi says. “It’s considered extremely rare to find even one piece of such pottery. We found about thirty.”

Naama Sukenik of the Israel Antiquities Authority, together with researchers from Bar-Ilan University, has analyzed residue on the Tel Shikmona sherds and concluded that the stains were made by the Hexaplex trunculus snail. Hexaplex trunculus provides a greater quantity of dye-making liquid than the other two color-producing species, Bolinus brandaris and Stramonita haemastoma, and is found widely in the Mediterranean. Soot marks have also been identified on the outer layers of the stained sherds discovered at Tel Shikmona, indicating that the thick-walled jars were heated as part of the dye-making process. Sukenik says the vessels likely had narrow openings to control the amount of air the yarn was exposed to during the process.

The storeroom cache contained an additional surprise: more than 200 loom weights and 60 spindle whorls, disc-shaped stone objects that speed up the process of hand-spinning raw wool. These artifacts indicate that a substantial workforce at the site was making wool into yarn, which was then dyed purple. “This is really a large number of spindle whorls,” Mendelsohn says, adding that the high quality of some of the objects, and the fact they may have been made from stone imported from Cyprus or Greece, suggests that those who used them were skilled professionals possibly connected with or originally from these places, which had long traditions of murex dyeing. “It seems Tel Shikmona wasn’t a residential site at all, at least not at this time,” says Shalvi. “It was a factory.” He adds that the fact that the settlement was surrounded by a defensive wall underscores how valuable the dye industry was.

Murex dyeing at Tel Shikmona appears to have ceased for a short time toward the end of the eighth century B.C. Archaeological layers from that period uncovered by Elgavish and analyzed by Shalvi contain no purple-stained vessels or sherds. This suggests that the Israelites may have taken Tel Shikmona over as part of their broader northern expansion, Gilboa says, ushering in a period of political instability and economic uncertainty that could have disrupted the dye industry. She adds that it’s quite possible that the Israelites did not use murex for dyeing.

About 100 years later, in the mid-seventh century B.C., the purple dye industry at Tel Shikmona underwent a resurgence. More stained sherds date to this period, and the pottery once again appears more typically Phoenician than Israelite. By then, the Assyrians had conquered much of the area that had been under Israelite control. However, the Phoenicians, who are known to have paid tribute to the Assyrians in exchange for some degree of independence, appear to have kept control of Tel Shikmona, or at least maintained a strong presence there. In the late seventh century, all evidence of dyeing at the site once again disappears, although archaeological layers from this period are difficult to study because construction later in antiquity disrupted them. It’s possible that economic turmoil resulting from the Assyrian invasion of the region and a later Babylonian invasion, around 597 B.C., are responsible, Shalvi suggests, although no signs of destruction have been found at the site. “Maybe they lost their markets for purple,” he says.

This would not, however, prove to be the end of murex dye. In the following centuries, the ascendant Persians, led by Cyrus the Great, who had wrested control of the region from the Babylonians, and later the forces of Alexander the Great, challenged the Phoenicians’ dominance of the Mediterranean sea trade. Although the excavated areas of Tel Shikmona don’t contain any sign of a dye industry during this era, archaeological evidence shows that purple dye production and textile dyeing continued widely around the Mediterranean, says Annalisa Marzano, an archaeologist at the University of Reading. As more people began to acquire purple and blue garments as part of a trend toward increased availability of luxury goods, Marzano says, “Settlements that did not have other resources could prosper on the production and export of purple dye and dyed textiles.” In another sign of more widespread consumption, the quality of the dye also began to vary, and certain areas became renowned for their superlative product. “In Asia the best purple is that of Tyre,” writes Pliny the Elder, “in Africa of Meninx [in modern Tunisia] and the parts of Gaetulia [in northern Africa] that border the Ocean, and in Europe that of Laconia [in Greece].”

As the dye became more widely available, various Roman rulers, starting with Julius Caesar (r. 46–44 B.C.), attempted to maintain its exclusive status by restricting its use to society’s elite. The emperor Nero (r. A.D. 54–68) is known to have fined those who wore certain shades of murex-based purple clothing without permission or who sold it to commoners. In the third century A.D., the Historia Augusta, a collection of emperors’ biographies, records that the industry had become tightly controlled by the government.

In his excavations of the Roman and Byzantine areas of the site, Eisenberg has identified soil from an industrial pool complex dating to the third and fourth centuries A.D. that is stained various shades of red and purple. Recent analysis of pollen samples taken from the plaster coating the pools indicates the presence of flax, which was often dyed with murex. There are also heaps of murex shells and a shallow pool carved from the rocks that features a dam on two sides. “This would have been a perfect place to capture and keep snails,” Eisenberg says, noting that in order to produce high-quality dye, the creatures would have been kept alive until just before their shells were cracked open. Luxurious fourth- and fifth-century A.D. villas originally uncovered by the Israel Antiquities Authority in the 1990s suggest Tel Shikmona’s inhabitants had grown wealthy, possibly on profits from the dye industry. This evidence has led Eisenberg to question the identity of the site during the late Roman period. “I think this is actually a place called Porphyreon,” he says, referring to a Roman town whose name means purple. A few texts, including the sixth-century A.D. account of a pilgrim named Antonini Placentini, indicate that Porphyreon was located in this region along the Carmel coast.

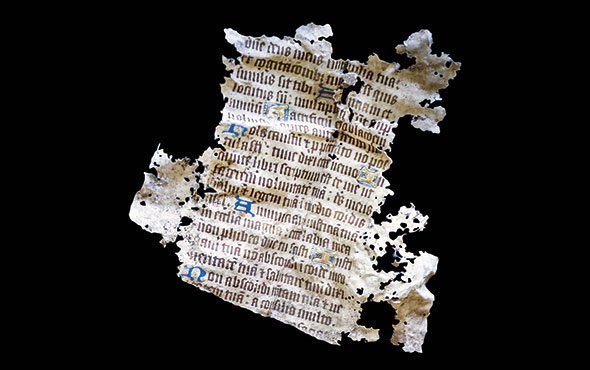

By the seventh century A.D., Tel Shikmona had been abandoned. In one of many parallels between the dye industry at the site and the fortunes of the region, broader use of murex dye also began to fade at this time, spurred partly by the rise of cheaper alternatives. The dye finally disappeared altogether in the fifteenth century, when its last major consumer, the Roman Catholic church, switched to a less expensive, insect- and plant-based dye to produce its clerical vestments.