When the Romans conquered Egypt in 30 B.C., the country’s system of temples, which had sustained religious traditions dating back more than 3,000 years, began to slowly wither away. Starved of the funds that pharaohs traditionally supplied to religious institutions, priests lost their vocation and temples fell into disuse throughout the country. The introduction of Christianity in the first century a.d. only hastened this process. But there was one exception to this trend: In the temples on the island of Philae in the Nile River, rites dedicated to the goddess Isis and the god Osiris continued to be celebrated in high style for some 500 years after the Roman conquest. This final flowering of ancient Egyptian religion was only possible because of the piety and support of Egypt’s neighbors to the south, the Nubians.

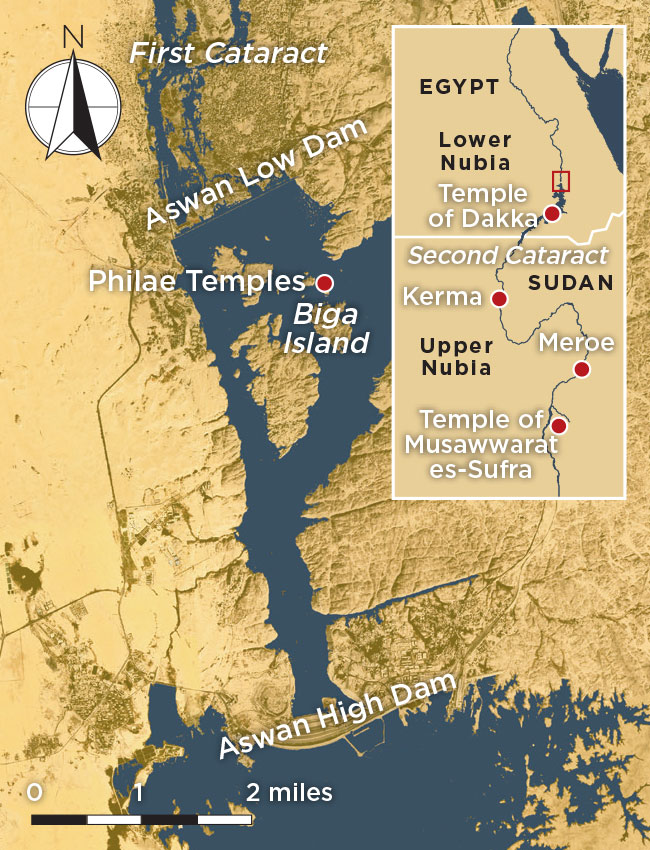

Philae lies just south of the Nile’s first cataract—one of six rapids along the river—which marked the historical border between ancient Egypt and Nubia, also known as Kush. In this region of Kush, called Lower Nubia, the temple complex at Philae was just one of many that were built on islands in the Nile and along its banks. Throughout the long history of Egypt and Nubia, Lower Nubia was a kind of buffer zone between these two lands and a place where the two cultures heavily influenced one another. “Often official Egyptian texts were demeaning to Nubians,” says Egyptologist Solange Ashby of the University of California, Los Angeles. “But this cultural arrogance doesn’t reflect the lived reality of Egyptians and Nubians being neighbors, intermarrying, sharing cultural and religious practices. These were people who interacted for millennia.”

From 300 B.C. to A.D. 300, Nubia was ruled from the capital city of Meroe. The Meroitic kings took a special interest in Philae, where the most important Egyptian temple dedicated to Isis was located. In part this may have been because the island had been significant to the Nubians for centuries. Even its ancient Egyptian name, Pilak, which means “Island of Time” or “Island of Extremity,” may have been of Nubian origin. And while many of the other temples on Philae were built by Egypt’s Ptolemaic kings, Greek rulers who held sway from 304 to 30 B.C., the continued survival of the religious practices there owed much to the Meroitic kings. They, and later other Nubian rulers, funded annual celebrations at Philae and devoted resources to maintaining its temples in the centuries before Christianity finally eclipsed Egypt’s ancient traditions.

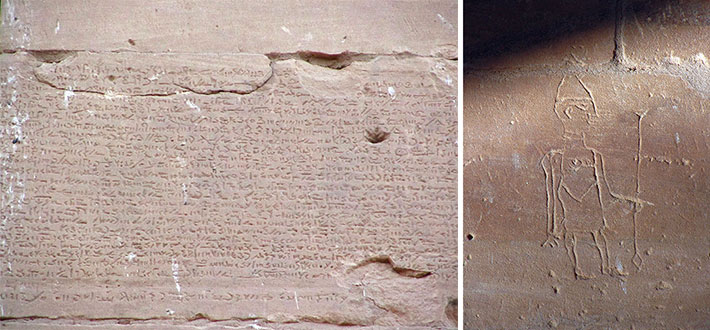

Recent research has highlighted the deep and enduring nature of this connection. Ashby has studied a corpus of ancient inscriptions recorded at Philae in the early twentieth century by British Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith and, more recently, by the late Egyptologist Eugene Cruz-Uribe of Indiana University East. Among these, she identified at least 98 inscriptions that were written on the walls of the temples at Philae on behalf of Nubians. These are mainly in the form of prayers offered to the gods. These inscriptions were written mostly in Greek and Demotic, a script used for writing ancient Egyptian, though some were also written in the Nubians’ own Meroitic script, which remains largely undeciphered. Ashby expected the inscriptions to have been commissioned by Nubian pilgrims to Philae, but she found that many were left by Nubians who had a much deeper connection to the island. “High-ranking priests, temple financial administrators, and officials were sent to Philae as representatives of the king in Meroe,” says Ashby. “Those Nubians eventually held power in the temple administration.”

By exploring the millennium-long presence of Nubians at Philae, Ashby and other researchers are asking questions not only about how Nubians celebrated their own beliefs and combined them with traditional Egyptian religious practices, but also about how they kept Egyptian rituals dedicated to Isis and Osiris alive long after they had died out elsewhere in the land of the pharaohs.

Today, the island of Philae lies submerged as a result of the construction of the Aswan High Dam. All the complex’s structures were moved to higher ground on the nearby island of Agilkia in the 1960s and 1970s. These include the island’s main temple, dedicated to Isis, and its entryway of two monumental sets of pylons, as well as a number of smaller temples dedicated to other gods. Archaeological excavations on the island prior to the flooding showed that, for much of Egyptian history, Philae was not a major Egyptian religious site along the lines of Thebes or Memphis, but that it did seem to have long-standing significance to Nubians. This may have had to do with its proximity to the island of Biga, where Nubians worshipped Hathor, a goddess who took the form of a cow. Hathor was especially revered in Nubia, where many people were pastoralists.

The earliest clear evidence of the Nubian connection to Philae dates to the reign of the Kushite kings who invaded Egypt in the eighth century B.C. and ruled it for nearly a century as the 25th Dynasty. One of the dynasty’s mightiest pharaohs, Taharqo (r. 690–664 B.C.), oversaw the construction of new temples and a revival of ancient Egyptian culture in the Nile Valley. This included commissioning a complex at Philae dedicated to Amun, a chief ancient Egyptian and Kushite deity closely associated with kingship. Blocks from this temple inscribed with Taharqo’s name were unearthed in the twentieth century before the island was submerged.

A number of extant small temples in the forecourt of the temple of Isis that were dedicated to Nubian gods provide further evidence that Philae was significant to Nubians. One such temple was devoted to Arensnuphis, a local god of Lower Nubia who is often depicted as a desert hunter and companion of Isis, and who sometimes appears as a lion. Another small temple, in the form of a kiosk, or a colonnaded pavilion, was built at Philae during the reign of the pharaoh Nectanebo I (r. 380–362 B.C.), founder of the 30th Dynasty, the last native-born Egyptian dynasty. Cruz-Uribe proposed that the building was used as a shrine for a hybrid Nubian-Egyptian god known as Thoth Pnubs, whose name links him to the ancient Nubian city of Kerma, which was known as Pnubs to the Nubians. There was also a small temple at Philae dedicated to the Nubian deity Mandulis, a sun god associated with the nomadic people known as the Blemmyes, who lived in the deserts to the east of Egypt and Nubia. “There are all kinds of Nubian religious activities that happened before the Ptolemaic Isis temple was erected,” says Ashby.

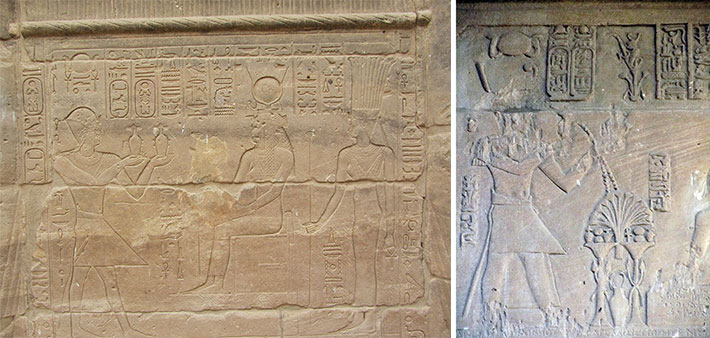

Another piece of evidence linking Nubian religious practices to Philae is found on some of the massive reliefs in the island’s temples that depict Ptolemaic pharaohs and other important religious officials offering libations to gods, often Isis and Osiris and their son Horus. In Egyptian mythology, Osiris was killed and dismembered by his brother Seth. Their sister and Osiris’ wife, Isis, managed to reassemble his body and he was brought back to life as the god of the underworld. The Egyptians offered libations, usually water or wine, to Osiris during rituals intended to symbolically aid in his rebirth. At Philae, depictions of this ritual include examples that show Ptolemaic pharaohs offering Osiris water in two small bottles, as was customary in Egyptian practice. However, others appear to show them offering Osiris libations of milk, which they pour out before the god from a situla, a long narrow vessel with a looped handle. This, Ashby believes, was a distinctly Nubian practice. “What we see at these temples is this different type of libation, which is to pour out a stream of milk that goes over offerings laid out on an offering table,” she says.

Egyptologists have debated for a century whether or not these scenes are intended to depict milk libations or offerings of wine or water. “I say this is milk,” says Ashby. She points to a scene inside the temple of Isis at Philae depicting Ptolemy VIII (r. 170–116 B.C.) offering a libation to Osiris, with Isis standing behind the god. “The hieroglyphs around him say this milk comes from the breast of the goddess Hesat,” Ashby explains, referring to a celestial cow goddess. Some scholars have argued that even if the depictions show milk libations, they must represent an Egyptian tradition. For Ashby, even though the depictions of the milk libation occur in Ptolemaic temples, the ritual is a purely Nubian practice. “I suggest they adopted it from Nubian worshippers,” she says. She points out that the earliest depictions of milk libations are found in Lower Nubia at the temple of Dakka, in a sanctuary that was built by the Meroitic king Arkamani (r. 275–250 B.C.). Milk libations are also depicted in royal funeral chapels farther south, in Upper Nubia, which is part of modern-day Sudan. At the temple of Musawwarat es-Sufra, for example, reliefs depict herdsmen preparing milk offerings for the Nubian lion-headed god Apedemak. But there are no such depictions in temples north of the first cataract, in Egypt proper.

Hieroglyphs at Philae’s temple of Isis refer to milk as ankh-was, or “life and power.” “Milk seems to be infused with this magical element of transferring life and power to the one who is deceased, much in the way that the breast milk of a mother keeps her infant alive and growing,” says Ashby. “There seems to be this connection in the mind of Nubians.” For the Nubians, then, milk would have been the ideal offering to aid in the rebirth of Osiris.

Milk libation rituals would have been performed during annual funerary rites for Osiris. Known as the Festival of Entry, this ceremony was held during the month of Khoiak, in the early fall, when the Nile flooding reached its peak. Gilded statues of Isis and Osiris were taken from the Isis temple at Philae to boats moored outside a structure known as the Gate of Hadrian. They were then rowed across the Nile to the island of Biga, where Osiris was thought to have been buried. There, at a sanctuary known as the Abaton, milk libations were offered to the god.

Ashby notes that, until quite recently, milk played a central role in rituals surrounding death in Nubia. Within living memory, a widow would traditionally pour milk on her husband’s grave on the second day after his death, a distant echo, perhaps, of the milk libations offered to Osiris.

EXPAND

The Enduring Cult of Isis

The earliest mention of the Egyptian goddess Isis occurs in the late 5th Dynasty (ca. 2465–2323 B.C.), in the funerary writings known as the Pyramid Texts. As the wife and chief mourner of Osiris, the god of the dead, Isis played a central role in Egyptian, and later Nubian, concepts of royal power and in rites celebrating the dead. As the mother of the god Horus, she was considered the embodiment of perfect motherhood.

Though Isis was the most powerful magician and healer among the gods, she did not have her own dedicated temples until late in ancient Egyptian history. Nectanebo II (r. 360–343 B.C.), the last native Egyptian pharaoh, was the first king to commission a temple dedicated to Isis, choosing to build her sanctuary at the site of Behbeit el-Hagar in the Nile Delta. The Macedonian pharaohs of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (305–30 B.C.) dedicated many more to Isis throughout Egypt, including those on the island of Philae.

The worship of Isis at temples in the seaside Ptolemaic capital of Alexandria drew the attention of seafarers from across the Mediterranean. They adopted her as a patron goddess and spread her cult throughout the Greco-Roman world, where she was assimilated with goddesses of fertility such as Demeter and Venus. Outside of Egypt and Nubia, where she retained her queenly status, she eventually lost her association with royal authority. From Britain to Afghanistan, the cult of Isis may have especially appealed to women and slaves.

Temples to Isis were also built across the classical world. One of the best preserved is the Temple of Isis at Pompeii (see “Digging Deeper into Pompeii’s Past”), whose vivid murals depicting the goddess were widely celebrated when they were first unearthed in the eighteenth century. Some scholars believe the temple so impressed Mozart, who visited in 1769, that it heavily influenced the composition of his most mystical opera, The Magic Flute.

As Christianity began to displace the worship of traditional gods throughout the Roman Empire, the cult of Isis also withered, enduring at Philae thanks to the patronage of Nubian royalty. As late as A.D. 452, the Nubian Blemmye people demanded in a treaty with Rome that they continue to be allowed to worship the goddess at the temples of Philae and retain the right to take a sacred statue of Isis to Nubia once a year.

Traditionally, the death knell of the worship of Isis—and ancient Egyptian religion at large—is dated to A.D. 536, when the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. A.D. 527–565) sent a military contingent to Philae to arrest the priests of Isis, stamp out pagan worship, and take the island’s treasures back to Constantinople. But the goddess’ presence endured long after the temples at Philae were closed. Indeed, many scholars believe that early images of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus were heavily influenced by depictions of Isis nursing the baby Horus.

During a rebellion against Ptolemaic rule in southern Egypt that lasted from 205 to 186 B.C., Meroitic rulers seized control of Lower Nubia and took possession of Philae’s temple precincts. Once Ptolemaic forces regained control of the region, the Nubians were forced to pay an annual tax to the priests at Philae. This ensured they would be allowed to continue visiting the island to worship their own gods. Prayer inscriptions left on the walls of the temples during this period were made by Greek and Egyptian officials and pilgrims, but none were left by Nubians.

That changed once the Romans annexed Egypt and temple revenues began to dwindle. Ashby has identified several inscriptions at Philae dating to between 10 B.C. and A.D. 57 associated with the names of Nubians who were active there. Their titles indicate they were local Nubians who were leaders of cult organizations or village elders. Written in Demotic, the inscriptions were left mainly on the walls of temples dedicated to Nubian gods. They record mandatory donations to singers at temples or to specific temples, including those honoring the Nubian gods Arensnuphis and Thoth Pnubs. During this period, the forecourt of the temple of Isis was expanded, probably to accommodate the numbers of Nubians coming to worship on Philae. While there do not seem to have been Nubian priests at Philae during the early Roman period, Nubians were involved in the temple administration, and were perhaps in a position to monitor how their tithes were being spent.

A second group of inscriptions Ashby has identified date from A.D. 175 to 275 and reflect the pinnacle of Nubian influence at Philae. Many of these inscriptions were commissioned by Nubians who, by this point, were active as priests at the top of the religious hierarchy. The inscriptions, which were made populain the most restricted areas of the temples, show that Nubians were claiming the loftiest religious titles, such as prophet or purity priest, as well as Meroitic titles such as the King’s Son of Kush and the Royal Scribe of Kush. The inscriptions also refer to the Nubian priests’ astronomical knowledge and imply that they were fluent in Egyptian, Greek, and Meroitic. Most prominent in the inscriptions are five generations of a Nubian family known as the Wayekiyes, who were powerful priests and who had both religious and military obligations.

Many of the inscriptions in the most sacred spaces refer to the annual Festival of Entry celebrations that honored Osiris and Isis. While some Egyptian names do appear in references to the festival, most of the participants appear to have been Nubian, in particular members of the Wayekiye family, says Egyptologist Jeremy Pope of the College of William and Mary. “In addition to being a focus of sincere piety, theological reflection, and communal bonds,” he says, “the worship of Isis would also have been important to elite Nubian families like the Wayekiyes as an occupation, a mark of social status, and thus a source of political power.”

Ashby says that Nubian inscriptions tend to be clustered together at Philae in particular buildings, such as the Gate of Hadrian and a room in the temple of Isis known as the Meroitic Chamber. She notes that Nubians seem to have been especially interested in leaving inscriptions near depictions of milk libations, reinforcing their importance in Kushite rituals. The Nubian expressions of piety also differ from those left by Greeks, which are short, often one-line inscriptions, and by Egyptians, which tend to be dry and repetitive. “They are much more heartfelt, longer, and more reverent toward Isis,” says Ashby. “They often have very dramatic phrases, such as ‘I am bending my arm, I am calling out to you, Isis!’” It’s likely that Nubians recited these prayers aloud in front of the reliefs and statues depicting Isis and Osiris.

The inscriptions are not just filled with pious expressions. They also detail particulars of the annual voyage made by envoys from the kings of Meroe to the Festival of Entry, such as the amount of gold the Meroitic rulers sent to Philae. The longest such inscription was written on behalf of one of Meroe’s envoys to Rome, a man named Sasan. Dating to April 10, A.D. 253, this is not just the longest Demotic inscription at Philae, but the longest known in Egypt. Its 26-line text suggests that Nubian pilgrims and priests journeying to Philae played both political and religious roles at the temples. In the inscription, Sasan discusses how he was commanded by the king of Meroe to set aside funds and throw a party for the entire district. “When these Nubian priests came, the local population would have been so excited to see them arriving on their majestic ships down the Nile,” says Ashby. “They knew that the Nubians were coming with pounds and pounds of gold, and that part of that money would be used to buy and slaughter animals and to provide beer, music, and dancing.” The entire district, the inscription says, celebrated for eight days in the forecourt of the Isis temple at Philae. From a long colonnade along the west side of the island, people could watch as Sasan crossed the Nile with his entourage to the Abaton sanctuary on Biga to worship Osiris. Another festival sponsored by the kings of Meroe was nearing its end, and Philae’s coffers were replenished for another year.

Nubian sponsorship of the temples at Philae ensured the continued survival of the worship of ancient Egyptian gods for centuries. But by the fourth century A.D., Christianity had begun to win many converts in the region. Around this time, Meroe fell to the Axum Empire, based in modern-day Ethiopia, ending Nubia’s contribution to the rites at Philae. Christians and adherents of traditional Egyptian and Nubian religions, however, continued to share the island for at least another 100 years. Ashby has found that a number of Nubian inscriptions date to this period, from about A.D. 408 to 456. These were made by priests representing the kings of the Blemmyes and included religious officials known as the prophets of Ptiris, a crocodile-like Nubian god. A Nubian family known as the Esmets served at Philae as priests for three generations, and its members eventually attained the rank of First Prophet of Isis. But the inscriptions they left were in isolated and marginal areas of the temple complex, suggesting that the priests no longer had access to the most sacred spaces. They even made inscriptions on the roof of the Isis temple, probably placed there to avoid scrutiny by Christians. One Demotic inscription, on the western wall of the temple of Isis, refers to “an abominable command,” possibly an allusion to the A.D. 435 edict of the Roman emperor Theodosius II (r. A.D. 408–450) that called for the destruction of all pagan temples in the empire. The last Demotic inscription was written in A.D. 452 on the roof of the temple of Isis, and the last pagan Greek inscription was made in A.D. 456.

The Nubians continued practicing their traditional religion at Philae until the Byzantine emperor Justinian (r. A.D. 527–565) outlawed pagan worship on the island. Perhaps nothing better illustrates the manner in which the Nubians preserved these ancient traditions than a hieroglyphic inscription inside the Gate of Hadrian that accompanied a depiction of the sun god Mandulis. The inscription was made by Esmet-Akhom, a member of the Esmet priestly family, and refers to words spoken by Mandulis “for all time and eternity.” It dates to A.D. 394 and is the latest hieroglyphic text known anywhere. “This final hieroglyphic inscription was made for a Nubian god,” says Ashby. For her, it comes as no surprise that the site where the last Egyptian hieroglyphs were written was, in fact, a sacred Nubian space.