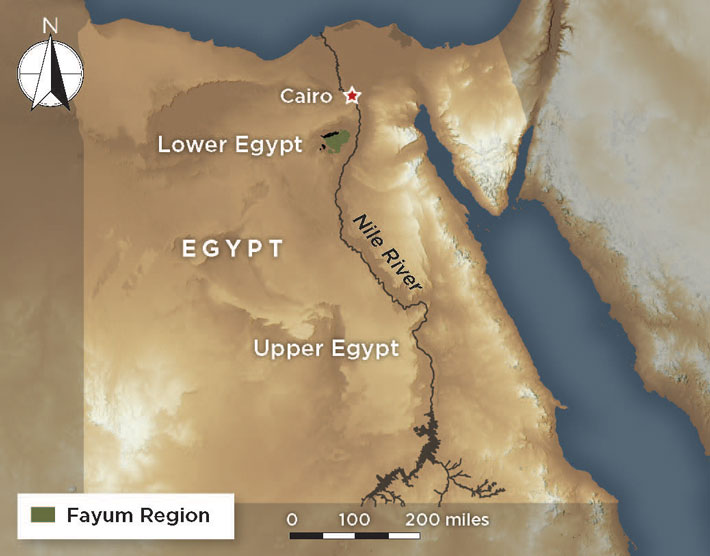

More than 1,000 mummy portraits, painted on wood panels or cloth shrouds between the first and third centuries A.D., are in museums today. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, archaeologists unearthed scores of these portraits, primarily at cemeteries in and around the Fayum region of Lower Egypt. Excavators often removed the panels or shrouds from the mummies, discarded the bodies, and sold the portraits to institutions throughout Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States. As a result, scholars have almost exclusively studied the portraits as works of art divorced from their archaeological and funerary contexts. They have focused their efforts on researching stylistic elements and establishing the identities and ethnicities of the deceased, whose names and biographies rarely survive. Few researchers have investigated how the paintings were made.

Nearly a decade ago, J. Paul Getty Museum antiquities conservator Marie Svoboda launched a project that would use materials science to study mummy portraits in collections around the world. “Because the panels are so well preserved, there is so much evidence of materials still present on them,” says Svoboda. “I’m interested in understanding the portraits in terms of ancient working practices.” To date, she has enlisted colleagues from 49 international institutions to collaborate on a project called APPEAR (Ancient Panel Paintings: Examination, Analysis, and Research).

Svoboda and her colleagues are examining panels using noninvasive techniques such as X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and broadband spectral imaging, as well as sampling tiny pieces of wood, to identify the types of timber, binding agents, and pigments at the ancient artists’ disposal. Thus far, they have studied one-third of all known mummy portraits. For the first time, scientists can now compare visual elements of the paintings as well as the materials and techniques artists used to create them. “By looking at large numbers of portraits, we can learn something more than from a one-off study,” Svoboda says. Little is known from ancient texts about funerary portrait painters and their practices, and archaeologists have uncovered few traces of painting workshops. By studying what remains on the paintings’ surfaces—and what lies beneath—APPEAR researchers are learning where artists obtained their materials, investigating how economic considerations might have motivated the choices of patrons and painters, and even revealing hidden brushstrokes that offer a glimpse of how artists created their work. In the future, their research may provide insights into regional differences among the portraits and into how people chose to represent themselves in death.

Beginning as early as the mid-third millennium B.C., Egyptians practiced artificial mummification as a way to preserve the bodies of deceased pharaohs and other wealthy individuals and convey them to the afterlife. In addition to being wrapped in cloth, bodies were often encased in elaborately decorated coffins featuring stylized masks. Over the millennia, these funerary traditions persisted, even as an increasingly cosmopolitan Egypt came under the control of foreign powers.

The Ptolemies, a dynasty of Macedonian royals who ruled Egypt from 304 to 30 B.C., when the Romans conquered it, opened new areas of the fertile Fayum for cultivation. As a result, many Greek settlers, who were granted land by the Ptolemies, flocked to the region. “A lot of immigrants came from all over the Greek East, including parts of Asia Minor, Cyprus, and other zones where Ptolemaic influence was strong,” says archaeologist Jennifer Gates-Foster of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Under the Romans, Fayum towns continued to prosper by supplying grain that fed the city of Rome.

After centuries of intermarriage, Greco-Egyptians made up a sizable portion of the Fayum’s population. “The Romans recognized the Fayum as a place that had this older connection to Greek identity,” Gates-Foster says. They established a new citizenship category for people who could demonstrate a certain amount of Greek ancestry, which afforded them favorable tax status and other civic rights.

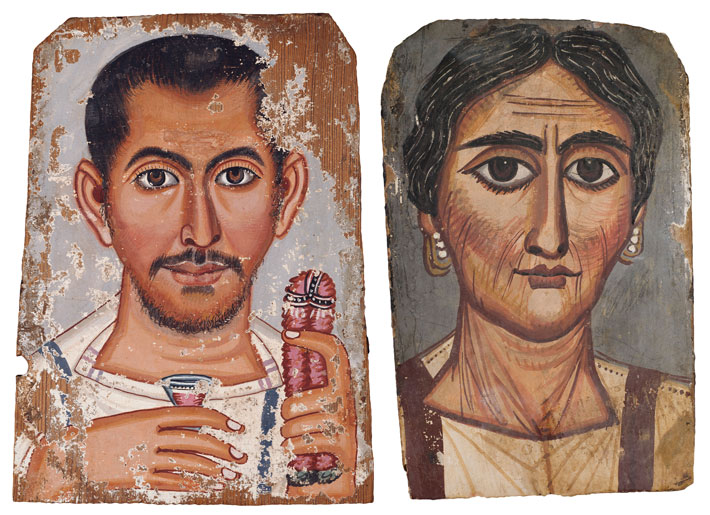

These changes in Fayum society are reflected in Roman period mummy portraits. “Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits represent a melting pot of cultures,” says Svoboda, noting that they blend the traditional Egyptian practice of mummification with Mediterranean stylistic elements. In contrast to the more stylized mummy masks of Egypt’s pharaonic period, which remained in vogue in more conservative Upper Egypt, Lower Egyptian portraits from the Roman period are more naturalistic, seemingly individualized depictions of the dead. The linen wrappings containing the body were often painted as well. And while many elite members of Fayum communities chose to have portraits included on their mummies, others opted for different types of burial depending on their personal wishes and financial means. “This is not a form of burial that would have been available to everyone,” Gates-Foster says. “It would certainly have been expensive and required a kind of cultural knowledge and access to craftspeople.”

APPEAR researchers are currently investigating the creative preferences and economic factors that might have motivated artists’ choices. For the painters who created mummy portraits, the task involved multiple stages, from picking the type of wood and choosing a painting technique to securing their desired pigments. First, an artist selected and prepared the wood. “Since most of the panels were curved to fit over the face of the mummy, you needed a wood that’s quite flexible,” says Caroline Cartwright, a senior research scientist at the British Museum. Thus, wood that could be cut into thin panels was desirable, though by no means always available. In earlier periods, trees had grown plentifully along the Nile’s banks, but high-quality wood was a rare commodity in Roman Egypt. Dowel holes, nails, and drill marks on some portrait panels are evidence that artisans occasionally recycled pieces of wood—some already hundreds of years old at the time they were reused—to use as canvases for new paintings.

In the past, curators were hesitant to permit researchers to analyze mummy portrait panels because accurate identification of the wood species required taking samples measuring more than two centimeters long. Advances in technology over the past few decades, however, have made the process much less destructive. “With the advent of scanning electron microscopes, which can offer huge magnifications of up to 300,000 times, samples are restricted to the size of a pinhead,” explains Cartwright, who has examined wood specimens from 195 panel portraits. Only 20 percent of the wood samples she has identified are native Egyptian species. Of those, most are made from the sycomore fig (Ficus sycomorus), a tree whose wood is lightweight, low quality, and susceptible to insect attack. During Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), the tree and its fruit were associated with the goddess Nut and played a role in funerary practice, which Cartwright believes may account for its use as a base for Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits. Other local woods, such as tamarisk (Tamarix aphylla) and sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi) are easy to work with, but only grew in certain areas and ecological zones.

Ancient portrait painters and the clientele who commissioned them, it seems, had a marked preference for imported types of wood. About 70 percent of the panels Cartwright has examined are made of lime wood (Tilia europaea), which came from Europe. Given its strength and elasticity, Cartwright says, this was a sensible choice for panel portraits. “Lime wood has an even texture and grain, and the cells are pretty uniformly sized,” she says. “It’s very suitable for applying really fine pigments.”

Artisans’ reasons for selecting other species of imported wood are less clear and were perhaps influenced by cultural and economic considerations. “There was a long history, particularly during the Middle Kingdom, of importing cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) to make both ordinary and high-status coffins,” Cartwright says. “I wonder if its use for mummy portraits represents a fusion of old and new traditions.” Artists also occasionally used oak (Quercus). Though strong, oak has to be cut thicker and thus isn’t flexible enough to curve over a mummy’s face. Cartwright thinks that imported oak might have been less expensive than imported lime wood, and that at least some panels were made in Europe and exported to Egypt as either semifinished or finished products. Both imported and local woods’ different properties, including varying degrees of flexibility, may suggest that some portraits were not intended solely to adorn mummies. Archaeologists believe that some may have been displayed in people’s homes before being incorporated into their mummy wrappings.

Once a portrait canvas, either wood or cloth, was selected and prepared, artists used different techniques and materials to apply pigments. One technique was tempera, which includes a quick-drying binding medium such as animal glue or plant gum. Another was encaustic, a method in which artists mixed pigments with molten beeswax and used heated tools to manipulate the resulting paint. “Panel painters probably had a preference for a certain medium and a setup for a particular painting technique,” says Svoboda, “and they had access to different types of binding media and pigments.”

Artists then applied pigments to a wooden panel or linen wrappings. The large number of mummy portraits from Roman Egypt has afforded APPEAR researchers an unusually broad view of the pigments, both naturally occurring and synthetic, that painters employed. Using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, researchers can map the chemical elements on a painting’s surface, which can help indicate which pigments were used. They can also examine the portraits using broadband spectral imaging techniques, which capture bands of light invisible to the naked eye. By employing a camera with special filters and light sources dialed to different wavelengths in the visible, ultraviolet, and infrared spectrums, researchers are able to characterize specific pigments by observing their luminescence, light absorption, and reflectance.

Ancient painters had a fairly small choice of colors in their palettes, so they often mixed them to create a wider range. “These artists were masters of their pigments,” Svoboda says. “They understood how to produce and use them, and how to achieve colors and illusions they wanted with the materials available to them.” One commonly used pigment was Egyptian blue, which had to be manufactured since naturally occurring, affordable blue pigments were rare. APPEAR researchers have found that Egyptian blue was a far more versatile material than they initially realized, and that painters used it to render garments and eyes, and even to create ruddy flesh tones. “Artists added a little bit of Egyptian blue to white pigments to make them more intensely bright or to add cool shadow tones,” says Svoboda. “They also mixed it with other colors to produce greens and purples, such as the famous Roman imperial purple.”

Another pigment frequently used in ancient Egypt was madder. A pink textile dye, it was also used for painting. While examining the garments in several portraits that were painted with madder, Svoboda and her colleagues noticed tiny fibers in the pigment. She thinks artists might have used wash water from the textile dyeing process to make the colored paint. “They were very economical and efficient in how they produced these portraits,” Svoboda says. “Maybe madder produced by the dye industry was more affordable.”

Artists were not limited to pigments that could be obtained locally. The linen wrappings of a fully intact mummy belonging to a young man named Herakleides are painted red, a ritually important color in ancient Egypt that evoked the setting sun and signified death and rebirth in the afterlife. Scientists from the Getty Conservation Institute detected this same red lead pigment on seven other mummy shrouds in museums affiliated with the project, including that of a woman named Isidora. “They discovered that this pigment was imported from southern Spain,” Svoboda says. This could indicate that the mummies were the work of a single painting workshop. Svoboda explains that lead’s toxicity suggests that painters also understood the science behind the materials they used. “To preserve something into the afterlife,” she says, “it makes sense to use a toxic material that would deter biological deterioration and pests such as insects or rodents.”

Imaging technologies are also providing rare evidence of painting practices. Under a microscope, researchers have been able to see preliminary drawings in white gypsum chalk on nine portraits from the same necropolis. One panel the researchers examined using infrared light was found to contain instructions written in Greek for completing the portrait. With a lighting tool called a CrimeScope, typically used by forensic scientists, Svoboda and her colleagues examined three other portraits and identified brushstrokes on them that appear as bright luminescent bands under layers of paint. Svoboda was able to see that, for a portrait of a young boy on linen, the painter layered a madder-based pigment under a darker red pigment to create the soft, fleshlike pastiness under his eyes. “The artist wasn’t just rendering with flat painting,” she says. “They were really trying to create shading, depth, and a subtle beauty in their style.”

Even though commissioning a mummy portrait was largely the preserve of the wealthy in the Roman period, the range of materials used and the variety in the quality of painting reflect differences even within the privileged ranks of society in Lower Egypt. For example, the expert painting and expensive pigments on the encaustic portrait of Isidora reveal that she was a woman of great financial means and social standing. “She is painted exquisitely and represented wearing very high-quality jewelry,” Svoboda says. “The artist had mastery of the materials and knew how to manipulate the wax.” By contrast, a roughly contemporaneous portrait of another woman is painted using tempera on a recycled wood panel. “Here we see a more simplistic style that indicates she was of a different class,” says Svoboda. “But the artist was still very creative with the pigments they used.” Instead of the gilding seen on Isidora’s portrait, this woman’s jewelry is painted with orpiment, a much more cost-effective pigment made from a mineral that looks and reflects like gold.

Although the identities of most of those represented in the mummy portraits are unknown, the individuals whose names are recorded are mostly Greek, including Herakleides and Isidora, and their portraits emphasize their Greek identity. At the same time, the paintings often underscore the mix of cultures that defined the communities in which they lived. “People are presenting themselves on a local stage,” says Gates-Foster, “but also desire to show themselves taking part in the broader provincial culture of the Roman Empire.” While most men are depicted wearing Greek-style garments that were common for prosperous, landowning men of the era, Roman citizens are painted in their traditional togas. Women are often shown with popular Roman hairstyles of the time, wearing vibrant clothing and lavish jewelry. Men, women, and children are often portrayed with various objects of personal, family, or religious significance. For example, many hold a pink flowered wreath to identify themselves as members of the cult of the goddess Isis; others show their affiliations with Serapis, the Greco-Egyptian god of the sun.

Although artists painted their subjects with some individualized facial features, they appear to have employed a relatively narrow range of stylistic conventions and characteristics in nearly all extant portraits. These include portraying people with a front-facing posture and large, prominent eyes. In many ways, the portraits represent idealized, aspirational depictions of individuals. Gates-Foster explains that the opulent jewels seen on women in the paintings, for example, certainly do not reflect accessories they wore on a daily basis. In fact, they might not even have owned such items. “In Roman Egypt, people constructed their mortuary iconography to meet certain criteria that, in the Egyptian understanding of the afterlife, were meant to preserve the body in its most beautiful form,” Gates-Foster says. “We’re not looking at a life portrait, but at an image that was intended to predict and support a reborn form of the individual.”

This, and the lack of actual bodies, makes it difficult for researchers to determine a person’s age at death simply by looking at their portrait. “Some studies have claimed that the portraits were painted in the prime of people’s lives, in their twenties or thirties, and were incorporated into their wrappings when they died,” says Svoboda. She does not think this was the case, however, at least not in every circumstance. There are surviving portraits of children and a handful of paintings depicting older individuals, with graying hair and wrinkles. CT scans of several mummies with portraits still attached, such as that of the 18-to-20-year-old Herakleides, have shown that the ages of those deceased individuals match the approximate ages at which they are depicted. “Most likely,” Svoboda says, “these portraits were painted at the time of death and represent a reflection of the person’s life.” Although scholars continue to debate the extent to which the paintings are intended to be accurate portrayals, they agree that they present a version of the deceased. “They can’t just be anybody, any face or individual,” Gates-Foster says. “There has to be something essential that they communicate about a person for their journey to the afterlife.”