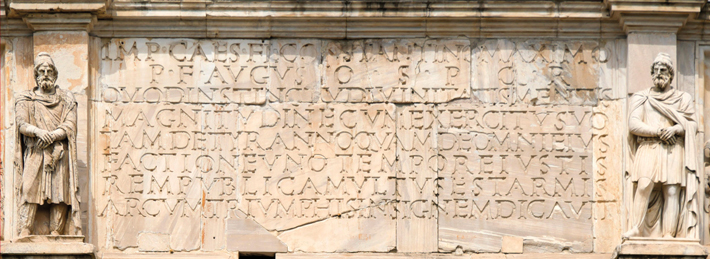

For the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantine the Greatest, pious blessed Augustus, because by inspiration of divinity, in greatness of his mind, from a tyrant on one side and from every faction of all on the other side at once, with his army he avenged the republic with just arms, the Senate and Roman People (SPQR) dedicated this arch as a sign for his triumphs.—Dedicatory inscription, Arch of Constantine, Rome

The pinnacle of an ancient Roman general’s or emperor’s military career was to be awarded the right to parade through the streets of Rome to celebrate his victories on the battlefield and flaunt the spoils of war in an extravagant display known as a triumph. During these grand spectacles, Romans watched as senators clad in brilliant white togas trimmed in purple made their way through crowded, noisy streets, followed by trumpeters and scores of other musicians, bulls to be slaughtered for feasts, and exotic animals captured in far-off conquered lands. Shackled prisoners, many of whom would later be executed, were hauled through the city, and heaping mounds of booty—gold and silver, marble statues, and more—were piled high on wagons pulled by draft animals. People craned their necks as the victorious general rode by in a four-horse chariot covered in laurel, the symbol of victory, holding a scepter and wearing a purple tunic, a decorated gold toga, a laurel wreath, and a gold crown. He was followed by his troops, whom ancient sources describe as singing loudly and shouting victory chants. Celebrating great military victories did not always end there. On occasion, the Senate also voted to build a monumental arch to celebrate the commander’s conquests. There were once 57 triumphal arches in Rome and more across the empire. Yet little is known about the vast majority of these monuments from contemporaneous or later sources, and no remains of them survive. Only three of the city’s triumphal arches still exist, the largest of which is the Arch of Constantine.

The arch celebrates the emperor Constantine’s (r. A.D. 306–337) victory over the usurper Maxentius (r. A.D. 306–312) at the Milvian Bridge just outside Rome on October 28, A.D. 312. For six years, the two had reigned as co-emperors. This battle brought an end to nearly a century of civil war and cemented Constantine’s place as the sole ruler of the Western Roman Empire. Sole rulership of the Eastern Empire would come 12 years later, at which time he became the ruler of the entire empire. The monument rises 69 feet high and measures 85 feet wide, and its decorations represent three centuries of imperial history. It has long been clear to scholars that much of the arch’s sculpture came from monuments dedicated to the earlier emperors Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–138), and Marcus Aurelius (r. A.D. 161–180). Other decorative elements of the arch were created at the time it was built. These include the dedicatory inscription along the top of both sides of the structure, as well as the winged victory figures flanking the central passageway and several reliefs inside the central passageway, some of which depict the sun god, Sol. The monument was topped by a gilded bronze statue of the emperor in his chariot.

Scholars have always believed that the six slabs of the frieze, which are above the two small arches at both the monument’s front and back, as well as on each of its two sides, are also Constantinian-era components. But University of Pennsylvania archaeologist C. Brian Rose has a different idea. “I always wanted to look into the problem of why the emperor’s heads were clearly re-carved and why the legs and feet of so many people depicted on the frieze are missing,” he says. “The more I read, the more interested I became and the more I thought these reliefs must be reused elements from some other monument.” This would, says Rose, mean rethinking more than a century of scholarship and creating a new biography of the arch.

In reconsidering the monument’s creation, scholars are also investigating how ancient viewers would have experienced it, and indeed this entire quarter of the city, which was packed with monuments dating from all periods of Rome’s past. By Constantine’s time, Rome had a 1,000-year history, and very little space remained in the city center for his architects to honor him. How they solved this problem and created a uniquely Constantinian space is a testament not only to their skill, but also to their understanding of the complex realities of the late Roman Empire, where awareness of the past was one way to ensure success in the future.

Repurposing pieces of architecture or architectural sculptures, often called spolia, or spoils, in new buildings was extremely common in ancient Rome. “There were monuments all over the city that either were torn down, falling down, or were never completed,” says Rose. “Pieces from these monuments were often warehoused and reused later.” This was especially the case after a fire devastated the city in A.D. 198. The greatest challenge for the senators who voted to fund the construction of Constantine’s arch was that they had only three years to complete it after the emperor’s victory over Maxentius so it would be ready for his decennalia, the celebration of 10 years of rule. “I think they used spolia because they wanted to do it quickly and cheaply,” Rose says. While the arch itself was purpose-built for the emperor, the builders would have searched their warehouses for scenes to showcase his virtues and military prowess. They eventually located nearly all they required.

The eight statues along the top of the arch were taken from the Forum of Trajan in Rome and depict enemy soldiers captured during his victorious early second-century A.D. campaigns against the Dacians in what is now Romania. Four slabs just under the arch’s roof and in its central passageway also depict scenes of the Dacian Wars. Between the Dacian soldiers, there are sculpted panels from a monument to Marcus Aurelius, possibly a triumphal arch. On the south side, the panels portray the emperor undertaking military duties such as welcoming an allied king, addressing his troops, and carrying out sacrifices before battle. On the north side, the panels include images of the victorious general returning to Rome accompanied by Mars, the god of war, and distributing funds to the populace. The eight sculpted roundels, or circular panels, on the arch were originally part of a monument built for Hadrian and show him hunting and performing sacrifices to Silvanus, the god of the woods; Diana, the goddess of the hunt; the god Apollo; and the semidivine hero Hercules. All the heads of Hadrian in these roundels were recut to transform them into a young Constantine. Although the ancient builders had these elements in hand, there was still the frieze for them to consider. Rose believes that, like the other sculptures, its panels were there for the taking.

The Arch of Constantine’s frieze is composed of six carved marble slabs depicting different scenes, five of which include the emperor: his adventus, or formal entry into Rome; an oratio in which he delivers a speech in the forum; a liberalitas in which he gives money to his subjects; a battle by a river; and troops besieging a walled city. The sixth shows a marching army.

When viewed from afar, these scenes are easily recognizable. Upon closer examination, however, four of them reveal some puzzling details—namely that the emperor’s heads were carved separately and that the legs and feet of many of the people depicted in the reliefs are missing. If the panels were carved expressly for Constantine’s monument, Rose reasons, why would the emperor’s head have been crafted separately, something that Roman sculptors never did? “The carving of heads as part of a relief’s surface is a feature of every imperial relief that has ever been found,” Rose says. “If they were carved separately, they would have been much less likely to remain attached.”

Rose suggests that at least four of the panels on the arch—the river battle, adventus, oratio, and liberalitas—were, in fact, taken from an unfinished triumphal monument, likely an arch, commissioned for the vicennalia, or 20 years of rule, of Diocletian (r. A.D. 284–305) in A.D. 303. During construction of the new arch, Rose argues, Diocletian’s heads were removed and replaced with heads of Constantine, which, not incidentally, have now fallen off these four panels. And as to the missing legs and feet? Rose believes they were cut off in the process of removing the panels from the existing monument before being reinstalled on the new arch. “I think that when they cut them off, they did it relatively rapidly,” he says. “They knew that it didn’t really matter if they had feet because it would be so high up no one would see this from the ground anyway.”

It is unusual, too, Rose explains, that the frieze’s scenes do not form a continuous narrative, as is the case on every other known triumphal arch. “An arch’s frieze normally shows a triumphal procession,” he says. “I wouldn’t expect that there would be six scenes from different places at different times if they were made for the arch.” The scenes depicting Diocletian were easily adapted to show Constantine. The Battle of the Margus River, which pitted Diocletian against his rival emperor Carinus (r. A.D. 283–285) in what is now Serbia—the first civil war scene ever included on a Roman triumphal monument—was transformed into the conflict at the Milvian Bridge pitting Constantine against Maxentius several decades later. And the scenes of the victorious emperor’s arrival in Rome, his speech, and his largesse, says Rose, were as appropriate for Constantine on his tenth anniversary as they had been for the earlier emperor on his twentieth.

When completed, the massive arch stood proudly near the end of the Triumphal Way, the ancient route of triumphal processions, amid a multitude of other imposing structures. These included earlier triumphal arches, the Colosseum, which dates to the first century A.D., and Hadrian’s Temple of Venus and Roma, Rome’s largest temple. This was one of the most heavily trafficked intersections in the city, and the arch was likely one of the most viewed monuments in Rome.

Past scholars have interpreted the reliefs as intended to link Constantine with the so-called good emperors—including Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius—of the second century A.D., a period of peace and stability. But Rose doesn’t believe the average viewer would have been sensitive to this messaging or have been disturbed by, or even aware of, the reuse of parts of a monument to Diocletian, an emperor who reigned at the end of the chaos and turbulence of the third century A.D. “I very much doubt if anyone who saw the arch would have known all of the monuments from which the sculptures came,” says Rose. “The heads were recut, and the point was to convey the virtues of the new emperor, not link him to any specific emperors of the second century.” Art historian Elizabeth Marlowe of Colgate University agrees that while they may not have recognized the particular monument from which a sculpture or panel came, nevertheless people would have been aware that they were taken from an earlier structure. “I think people would have known that those reliefs were older,” she says. “Constantine did so much in this part of the city to connect old Rome with the new Rome under his rule that I think this was a space where a viewer would expect to see that.”

Constantine decided not to clear out room in this highly symbolic area of the city to create his own forum, as many of his predecessors had. “He was the first emperor to see the center of Rome as a historical landscape and to think of it as an inherited architectural heritage to preserve and, when appropriate, to make his own,” Marlowe says. “Constantine was picking pieces of Rome’s long, imperial history and repackaging it—and himself—in a self-conscious way.” For example, the massive basilica built by the emperor’s rival Maxentius not far from the Colosseum was rededicated to Constantine, its entrance and orientation shifted, and a huge, seated statue of the new emperor placed in the structure to “offer the spectator a totally new, Constantinian experience of the building,” says Marlowe. This stands in stark contrast, for example, to the treatment given to the Domus Aurea, or Golden House, the gargantuan private palace built by the emperor Nero (r. A.D. 54–68) on the Palatine and Esquiline Hills overlooking this part of the city. After Nero’s suicide, his successors largely covered over the Domus Aurea and turned the new space into a public park. Other parts of the palace were torn down to make room for the Colosseum.

Marlowe believes Constantine also fashioned another very deliberate link to Rome’s past when selecting the location of his arch. To accommodate the arch in this densely packed, monument-filled area, Constantine’s architects made the unusual decision to erect it in an open space next to the Colosseum, at an odd angle to the Triumphal Way, not straddling it, as many previous arches had. “We think of the Roman notions of space as right angles and grids and symmetry,” Marlowe says. “The idea that they would build this monument even a little bit off-center radically defies our ideas of what Roman architecture and city planning were about.” Because the arch was not centered on the road, Marlowe explains, the emperor was able to mark the location with a Constantinian stamp.

At the time, a 125-foot-tall gilded bronze statue stood just over 350 feet from where the arch was to be erected. The colossus had originally been created to loom over the Domus Aurea and depicted Nero, or perhaps Nero as the sun god, Sol. It was moved to its location near the Colosseum by Hadrian during construction of the Temple of Venus and Roma. Rather than tear down the statue, which by that point had stood for 250 years and was likely a beloved landmark and symbol of pride for the city, Marlowe says that Constantine sited his new arch—itself a monument jammed with references to the past—so that a passerby walking down the Triumphal Way would see the immense statue framed by the new monument. “At some point the colossus would have been perfectly framed by the arch’s center passageway and would have lined up directly with a huge gilded bronze figure of Constantine in his chariot on the arch’s roof,” she says. “As you got closer, the glowing statue would have appeared to almost be descending until it completely filled the space of the arch. This would have gone a long way toward reassuring Romans and the Senate that Constantine respected the past, and toward cementing his relationship to Sol, a long-revered deity with whom he wanted to be identified.” When one finally reached the arch, it would have come as no surprise, then, to see Sol represented in many locations on the arch along with Constantine and the previous emperors. “The arch is something new and old at the same time,” Marlowe says. “It is, in fact, a microcosm of the whole city and its history.”