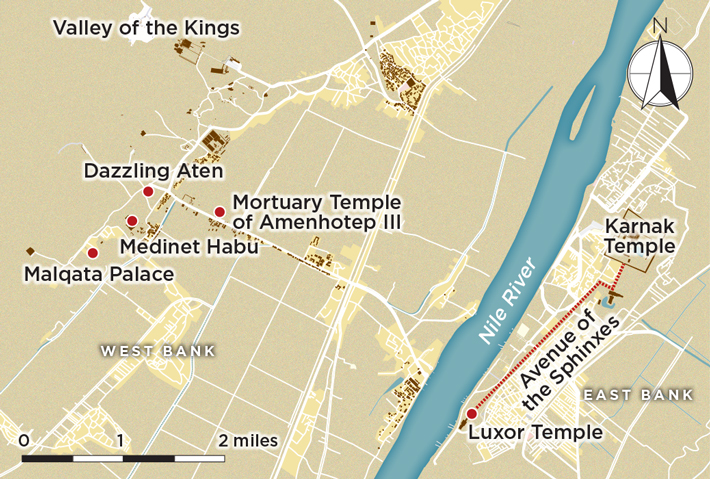

The banks of the Nile River in modern-day Luxor are strewn with so many ruins of Egypt’s illustrious past that the area is sometimes called the world’s largest open-air museum. Luxor was once ancient Thebes, the erstwhile capital of Egypt, and for more than 1,000 years, the pharaohs erected temples, monuments, and sculptures there as testaments to their power, wealth, and piety. The New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.), which many scholars believe was the cultural and artistic zenith of Egyptian civilization, was an especially prolific period. Among the archaeological sites on the Nile’s east bank are two of the largest and most important temples in all of Egypt, the Karnak Temple, called the “most selected of places” by ancient Egyptians, and the Luxor Temple, known to them as the “southern sanctuary.” These two massive religious complexes, both of which celebrated the holy Theban trinity of Amun-Ra, the greatest of gods, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu, still boast reminders of their former glory—ornate columns, giant statues, soaring obelisks, and expertly carved reliefs. The complexes were connected by an almost two-mile-long grand processional way known as the Avenue of Sphinxes, lined with more than 600 ram-headed statues and sphinxes carved in stone.

The most prominent archaeological remnants on the west bank, an area known to scholars as the “city of the dead,” are a group of mortuary temples built by some of the New Kingdom’s most notable rulers, including Hatshepsut (r. ca. 1479–1458 B.C.), Ramesses II (r. ca. 1279–1213 B.C.), and Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.). Mortuary or funerary temples were not where pharaohs were entombed, but where they were commemorated and worshipped for eternity after their deaths, alongside other Egyptian gods. Dwarfing all these complexes was the one known to have been built by Amenhotep III (r. ca. 1390–1352 B.C.).

Amenhotep III presided over Egypt during an unprecedented time that is often referred to as the Egyptian Golden Age. The pharaoh initiated an extraordinary building campaign that spurred urban growth in his capital of Thebes. He commissioned monumental structures such as his mortuary temple, the scale of which is only just beginning to be understood as a result of archaeological research over the past two decades. The picture of Amenhotep III’s “golden” Thebes has only been enhanced by the recent chance discovery of a previously unknown city built during his reign, now buried amid the monuments of the west bank. Some archaeologists consider this city one of the most important discoveries of the past century in Egypt. The remnants of both the temple and the city now stand as potent reminders of an era of peace and prosperity that preceded one of the most tumultuous periods in Egyptian history.

A century ago, in the autumn of 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter stunned the world with images of a tomb he had discovered in the Valley of the Kings on the Nile’s west bank. The photographs showed a small burial chamber filled with some 5,000 objects stacked nearly floor to ceiling, many of them made of gold. The tomb held the remains and funerary goods of Tutankhamun (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.), a relatively unheralded pharaoh who became Egypt’s ruler at the age of nine and reigned for only a decade.

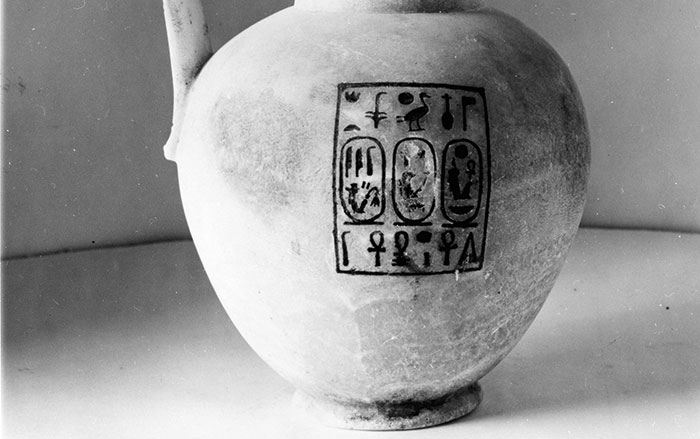

Archaeologists believed that, like several other 18th Dynasty (ca. 1550–1295 B.C.) pharaohs, Tutankhamun likely had a mortuary temple somewhere along the Nile’s west bank—but they had been unable to find it in such a vast area dotted with ruins. However, a clue to the temple’s location may have been buried with the pharaoh himself. Among the golden chairs, beds, and chariots was a relatively simple pottery vessel with an inscription suggesting that Tutankhamun’s temple was located near a place on the west bank known today as Medinet Habu. “The inscription indicated that the mortuary temple was built in the most sacred area of the god Amun, which is Medinet Habu,” says Egyptologist Zahi Hawass. “I thought further investigation was needed in this area.”

Following this small but promising piece of evidence, in 2020 Hawass began his quest to find the temple just north of Medinet Habu, near the site of the mortuary temples of Ay (r. ca. 1327–1323 B.C.) and Horemheb (r. ca. 1323–1295 B.C.), two of Tutankhamun’s successors. As the excavations unfolded, Hawass’ team failed to turn up definitive evidence of Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple, but instead found something unexpected. As they began removing layers of debris amassed over thousands of years, they gradually exposed a network of well-preserved mudbrick walls that seemed to extend in every direction. Eventually they revealed streets, houses, storerooms, artists’ workshops, and industrial spaces, along with at least 1,000 artifacts. Some of the walls still stood to a height of 12 feet. Yet the settlement was an enigma as no ancient records mention it. Scholars wondered when it was founded, who built it, and what it was called. The answers became apparent when Hawass uncovered a series of wine jars. Mudbrick seals used to close the vessels were inscribed with hieroglyphs that spelled out the name of the city—Tehn Aten, or “Dazzling” Aten, a name that unequivocally pointed to one ruler: Tutankhamun’s grandfather, the pharaoh Amenhotep III. “I originally called it the Golden City or the Lost City because it dates to the reign of Amenhotep III, which was the Golden Age of ancient Egypt, and because nothing was known about it,” Hawass says.

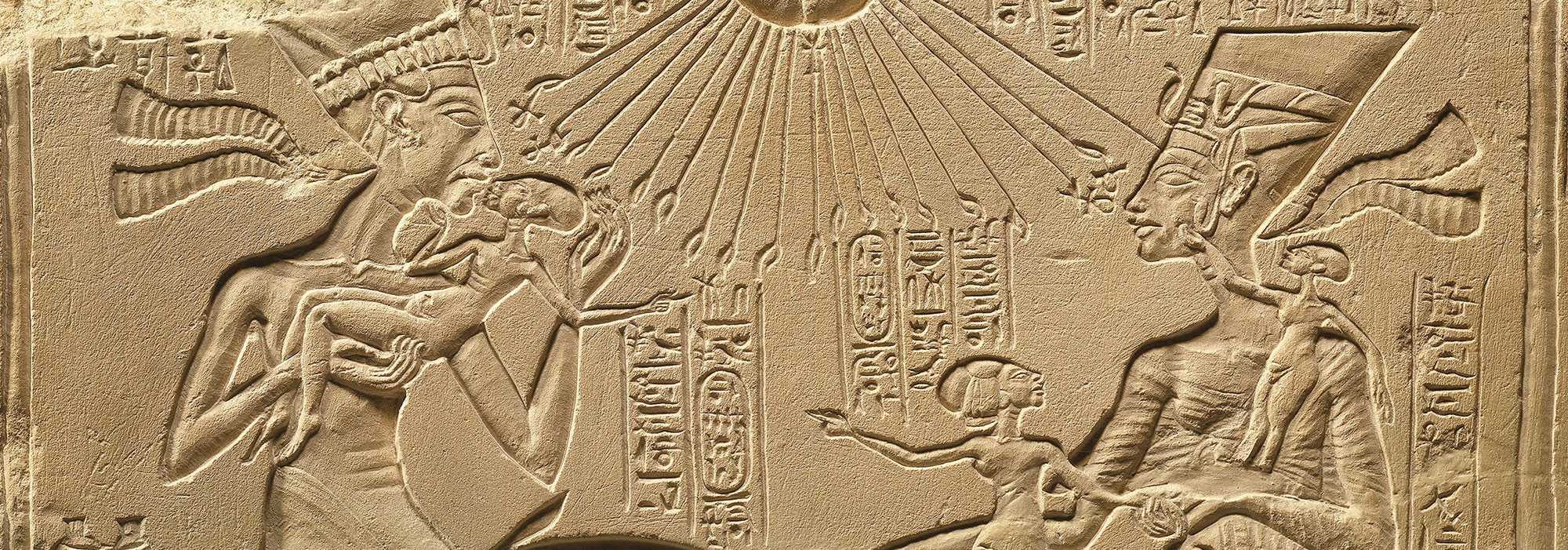

During the New Kingdom—with one brief interlude—Amun (or Amun-Ra), the supreme god, was worshipped as first among the Egyptian gods. Over time, however, Amenhotep III increasingly began to portray himself as a sun god and promoted a new aspect of the deity known as Aten to prominence. Aten was the disk of the sun, the giver of light and life, and Amenhotep III adopted the epithet “the dazzling Aten” for himself as well.

The city of Dazzling Aten was just one part of the extensive building program Amenhotep III carried out throughout Egypt. The pharaoh was responsible for commissioning some of the grandest monuments Egypt had ever seen, and he ruled during a period when Egyptian artists were extremely prolific—more statues of Amenhotep III survive today than of any other Egyptian pharaoh. Through his excavations, Hawass has discovered that Dazzling Aten was linked to Amenhotep III’s greatest project of all: his enormous mortuary temple.

Amenhotep III was the ninth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, one of ancient Egypt’s most storied bloodlines. Among its rulers were conquerors such as Ahmose (r. ca. 1550–1525 B.C.) and Thutmose III (r. ca. 1479–1425 B.C.), military commanders including Horemheb, the controversial king Akhenaten (r. ca. 1349–1336 B.C.), his renowned wife Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun, perhaps Egypt’s most famous ruler. The 18th Dynasty was the first dynasty of the New Kingdom and began when its founder, Ahmose, drove out the Hyksos, foreign kings who originally hailed from the Levant and who had ruled parts of northern Egypt for more than 200 years. Ahmose’s reunification of Egypt ushered in a period of unparalleled prosperity.

Amenhotep III achieved some military success by launching campaigns into Nubia early in his reign and benefited greatly from the martial exploits of his great-grandfather Thutmose III. He inherited a territory that stretched across more than 1,000 miles from modern Sudan to Syria. The gold that poured into his coffers from this great empire and the relative peace the country enjoyed enabled Amenhotep III to employ an army of expert architects, builders, painters, sculptors, and artisans who expressed the glory of his age in art and architecture. He commissioned the construction of and sponsored the restoration of temples and monuments up and down the Nile and transformed the capital of Thebes. On the east bank, he carried out extensive additions and renovations to the Karnak and Luxor Temples, as well as to smaller religious complexes. On the west bank, the pharaoh built himself a vast sprawling estate at the site of Malqata. This lavish complex was the largest residence in Egypt and included an artificial harbor measuring one and a half miles long.

Yet no building project of Amenhotep III’s compared to his mortuary temple, one of the grandest religious structures ever built. The entire temple precinct was once surrounded by a painted mudbrick wall that enclosed more than four million square feet, or around 95 acres. The first pylon, or main entrance, was guarded by two colossal statues of the seated king. A grand processional way then led through two additional elaborate pylons, the gates of which were flanked by a pair of giant statues of Amenhotep III as well. It then entered a great peristyle court with a forest of columns shaped like bundles of papyrus where hundreds of free-standing statues were installed. Near the rear of the complex was a temple dedicated to Amun-Ra, as well as the mortuary temple proper of Amenhotep III, where the dead king received the gifts and offerings that would sustain him in his journey through the afterlife.

Although Amenhotep III, like other pharaohs, called his mortuary temple the House of Millions of Years, in actuality it only lasted for a century and a half. Around 1200 B.C., a devastating earthquake reduced it to ruins. Its stones, bricks, statues, and other materials were carted off to be reused in nearby construction projects and to adorn new temples, especially those of the pharaohs Ramesses II and Merneptah (r. ca. 1213–1203 B.C.). What was left was periodically flooded, until most of the sanctuary was covered in six to 10 feet of alluvial deposits. The greatest temple in ancient Egypt had all but disappeared.

All that remained were the two gargantuan statues of Amenhotep III sitting at what had once been the temple’s main entrance. The northern statue was named Memnon by the Romans who associated it with the Ethiopian Trojan War hero-king Memnon, these behemoths each weigh more than 720 tons and rise to a height of nearly 70 feet. For more than 3,000 years, they towered above the Nile plain, but little else of the original structure was visible—that is, until the late 1990s, when Egyptologist Hourig Sourouzian began to lament the condition of the ruins and wonder what might still be buried beneath the surface. “The colossi were all you saw,” she says. “There were some column bases and fallen fragmented sculptures, but it looked like a field. I said, ‘I wish someone could do something to save this ruined temple.’” Sourouzian, with Rainer Stadelmann of the German Archaeological Institute and a few colleagues, made a proposal to the Egyptian authorities. They founded the Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III Temple Conservation Project, of which she is the current director. Over the past two and a half decades, her team has grown from a few scholars and a handful of workers to a total of more than 300. Their goal is to save the last remains of the temple from further degradation and to at least partially restore the parts that were felled by the earthquake or damaged by the passage of time.

The focus of Sourouzian’s project is mainly conservation rather than excavation, but she has occasionally found it necessary to dig in certain areas. “We have emergency cases to solve, but in order to conserve, we have to excavate to identify the objects that need to be conserved,” she says. “While cleaning and digging, we discovered so much. In the beginning, I could have never imagined there were so many things left to discover.” Within the temple precinct, Sourouzian and her team have unearthed tens of thousands of sculpture fragments that attest to the grandeur of the temple’s artistic program. Its halls and courts once teemed with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of statues. “Because Amenhotep III’s reign was so prosperous and because they had so many brilliant sculptors and artists in the workshops, they could produce so many sculptures,” says Sourouzian. “And each of them is an all-time masterpiece.”

To date, the team has reconstructed part of the peristyle court, which was once adorned with two huge stone stelas recording Amenhotep III’s accomplishments, as well as dozens of statues of the pharaoh and sculptures depicting sphinxes, a crocodile, a hippopotamus, falcon gods, and other deities. They have also discovered hundreds of statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet that once lined the court’s walls and passageways. Discovering such a great number of representations of the goddess is extraordinary, explains Sourouzian. “That our project would find so many was really a surprise,” she says. Scholars continue to question why effigies of the goddess were present in such great numbers in Amenhotep III’s temples; some suggest a plague may have ravaged Egypt at some point during his reign or perhaps Amenhotep III himself was ill and needed Sekhmet’s protection, Sourouzian says, because besides being a goddess who spreads illness, she also cures. Sourouzian believes that the abundance of statues may have also had to do with Sekhmet’s and Amenhotep III’s shared close connection with the sun. “After thirty years of reign, we know that this king celebrated his first jubilee, and later two more, and when he does that, he is assimilated to Ra and becomes a sun god,” she says. “Sekhmet is the manifestation of the daughter of Ra and she lights fires to annihilate the enemies of the sun. So Amenhotep surrounded himself with Sekhmets. You will find that the king made this monument to serve the gods, to be beneficial to them. The most important thing was to perform his piety.”

One of the project’s most daunting endeavors has been to reerect the temple’s enormous statues. In a painstaking process, each of the hundreds of fragments of a given statue is cleaned, conserved, and joined to neighboring pieces. Then, these massive stone figures, each weighing hundreds of tons, must be carefully lifted and set back in their original positions. “It’s hard work,” says Sourouzian, “but we are constantly fascinated by this extraordinary heritage and we are strengthened every day by knowing we have saved these ruins from oblivion and destruction.”

Thus far the team has successfully raised numerous sculptures within the peristyle court as well as the two 45-foot-tall striding statues of the pharaoh that were once positioned at the temple’s Northern Gate. Their largest undertaking has been reconstructing the pairs of colossi that once flanked the second and third pylons along the grand processional way. Before the project started, it was not known how much, if any, of these gigantic works had survived. To the excavators’ delight, they found that most of the statues’ bulk was still buried where the figures had fallen during the earthquake—and that both their state of preservation and their artisanship were awe-inspiring. Sourouzian was especially moved when she first saw the renderings of Amenhotep III’s wife Tiye, whose figure was carved next to the right leg of the pharaoh in each of the seated statues. “Four times I was surprised and joyful when we discovered the statues of the queen hidden under the four colossal statues of the pharaoh that we uncovered,” Sourouzian says. “It is unforgettable and I will always keep those moments in my eyes and heart.”

After decades of work, the splendor and grandeur of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple can finally begin to be imagined. Sourouzian believes that there would not have been a great deal of open space within the enormous enclosure. Instead, it would have been filled with smaller temples, courtyards, processional ways, gardens, pools, storerooms, and priests’ quarters. Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple would have rivaled the great Karnak Temple across the river, but that complex was added to and built up over a period of 2,000 years until it eventually became the largest religious complex in the world, a distinction it retains. By contrast, Amenhotep III’s temple was completed during his 39-year reign. “Each Egyptian king liked to say they had done things that had never been seen before and that they surpassed all that was done in the past,” says Sourouzian. “But Amenhotep III really did surpass many things that were done before him. It’s a fantastic achievement which corresponds to the height of Egyptian civilization.”

Evidence of one way the pharaoh was able to accomplish this may lie just a few hundred yards away from his mortuary temple. The logistics of supplying and maintaining a complex of this size would have been extremely complicated and involved thousands of people. It would have required its own support city, one that, in fact, eventually rose just beyond its gates—the city of Dazzling Aten. Hawass’ ongoing excavations have thus far uncovered parts of three separate districts surrounded by serpentine walls. These districts were likely part of an even more extensive settlement—which may have reached the gates of Amenhotep III’s Malqata Palace to the southwest and Deir el-Medina to the north, where the workers who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings lived. For Hawass, this new discovery dispels the misconception that, unlike other contemporaneous cultures, ancient Egypt lacked major metropolises. “It is the largest ancient Egyptian settlement ever found,” he says. “Egypt was not a civilization without cities.”

Dazzling Aten had residential and administrative quarters, where people lived and royal officers carried out official business, but perhaps its most telling characteristic was its industrial space. There were numerous workshops producing faience jewelry, clothes, sandals, leather goods, food, and even toys for children living in the Malqata Palace. “The city really existed to provide the palace and the temples with what they needed,” Hawass says. Most recently, a large lake was discovered north of the city that provided fresh water not only for drinking and cooking, but also for the city’s booming mudbrick industry, which manufactured the materials for Amenhotep III’s building projects.

There is even evidence that sculptors working and living in Dazzling Aten created the hundreds of statues that once decorated the great peristyle court of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple. “We have uncovered a workshop where the statues of Sekhmet were crafted,” Hawass says. “I believe they were all built in this city.” It’s also likely, he says, that some of the extra-ordinary objects that would be entombed with Tutankhamun just a few decades later were originally crafted by Dazzling Aten’s artisans. “It was the Golden Age of the New Kingdom,” says Hawass, “but if anyone closes their eyes to imagine the magnificence of this area with the palaces and the city of Dazzling Aten and the funerary temple, it goes beyond that, especially in the architecture and statuary.”

The city changed drastically after Amenhotep III’s death, as his son, Amenhotep IV (r. ca. 1353–1349 B.C.), enacted radical religious changes that brought great turmoil to Egypt. Although Amenhotep III had been the first ruler to favor the sun disk Aten as a god, he was careful not to neglect the other popular gods and goddess of ancient Egypt. His son did not follow his example. Amenhotep IV elevated Aten to a position as Egypt’s sole and superior deity, denigrating Amun and the other Theban gods, and introducing a type of monotheism that was anathema to the Egyptians. Five years into his reign, he changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning “Effective of the Aten.” He also named his son Tutankhaten, the “Living Image of Aten.”

Akhenaten slighted the powerful class of temple priests, which put him in a very tenuous position in Egypt’s capital at Thebes, the holy city of Amun. Rather than take on the priests in their power center, the pharaoh founded a new capital, which he built on virgin desert around 250 miles north. He called it Akhetaten, or “Horizon of the Aten”; today it is known as Amarna. In Thebes, Dazzling Aten, which had been home to so many workers and craftspeople whose livelihood depended on royal employment, was deserted nearly overnight. “The people picked up, went to Amarna, and left the city as it was,” says Hawass. “Some even closed and boarded up their houses, which is why the city was found completely intact.”

Archaeologists are still searching for evidence of whether Dazzling Aten was reoccupied after Akhenaten’s young son abandoned his father’s city and restored Thebes as Egypt’s capital and Amun as the supreme god. He dropped the Aten from his name and changed it to Tutankhamun, the “Living Image of Amun.” This did not, however, stop his eventual successor Horemheb from trying to wipe Tutankhamun from the historical records along with his father for their perceived heresies, scarring the family legacy. The 18th Dynasty, which had ruled Egypt on the strength of a single family and its allies, finally came to an end after two and a half centuries, but not before its members, and especially Amenhotep III, had changed the face of Egypt forever.

-

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty September/October 2022

The Divine King and His Queen

(bpk Bildagentur/Egyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung Staatliche Museen/ Berlin/Germany/Art Resource, NY)

(bpk Bildagentur/Egyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung Staatliche Museen/ Berlin/Germany/Art Resource, NY) -

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty September/October 2022

Who Was Tut’s Mother?

(Ken Garrett)

(Ken Garrett) -

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty September/October 2022

Tut the Antiquarian

(Griffith Institute, University of Oxford)

(Griffith Institute, University of Oxford) -

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty September/October 2022

The Pharaoh’s Daughters

(Ken Garrett)

(Ken Garrett) -

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty September/October 2022

Who Came Next?

(HIP/Art Resource, NY)

(HIP/Art Resource, NY) -

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty September/October 2022

A Foreign Affair

(Scala/Art Resource, NY)

(Scala/Art Resource, NY)