Los Angeles’ first Chinatown was settled starting around 1880, south of the city’s historic center, the Los Angeles Plaza. Over the next two decades, the densely populated neighborhood expanded to the northeast and became home to a range of Chinese-owned businesses. These included markets that sold fare such as plum sauce for seasoning roast meat and restaurants that served up delicacies such as bird’s nest soup and century eggs. Like all Chinese immigrants to the United States, Chinatown’s residents suffered from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred most Chinese laborers from entering the country and led to harsh scrutiny of those already present. Its population peaked around the turn of the twentieth century and then began to decline, as it was provided almost no municipal services. The enclave was largely razed in 1934 to make way for a new railway terminal. A few years later, a pair of competing projects—China City and New Chinatown—were established about a mile from the old neighborhood, and later merged to form the Chinatown that exists to this day.

Construction of a subway station in the late 1980s to early 1990s offered a team led by archaeologist Roberta Greenwood of Greenwood and Associates the opportunity to excavate a portion of the city’s original Chinatown. The team uncovered a vast array of artifacts, including ceramics, glass, metal, plant remains—and 4,506 animal bones that offered clues to what people in the neighborhood ate. The evidence suggested that pork was by far the most widely consumed meat—and many of the pork bones had been chopped into one- to three-inch lengths suitable for grasping with chopsticks.

While researching other Southern California Chinatowns at the San Bernardino County Museum in 2022, archaeologists Jiajing Wang of Dartmouth College and Laura Ng of Grinnell College came across boxes of animal bones from the Los Angeles Chinatown excavation. “I opened one box and found lots of pig jaws,” says Wang. “I knew we could do some sort of residue analysis on the teeth.” In the late nineteenth century, the completion of the transcontinental railroad and introduction of refrigerated railcars enabled countrywide distribution of pork raised on large Midwestern farms. However, there was some evidence that butcher shops in Los Angeles’ Chinatown—and possibly even Chinatown residents themselves—raised their own pigs for slaughter. By analyzing plaque on the pigs’ teeth, which often includes food remains, Wang and Ng hoped to find out what the animals had eaten and thereby determine where they had been raised.

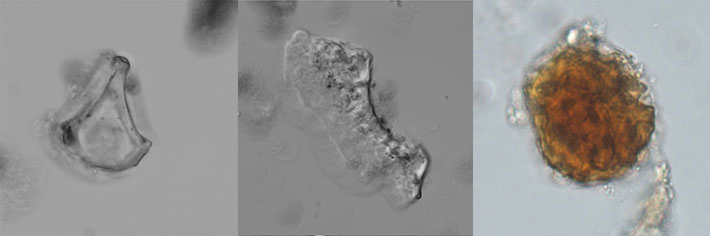

Wang selected specimens from 10 different pigs that had been found in two trash deposits. In the tooth plaque, she found microscopic plant particles called phytoliths that indicated the pigs had eaten rice husks and leaves. She also found eggs of parasitic roundworms. However, there was no evidence that the pigs had eaten corn, meaning they could not have come from industrial Midwestern farms, where corn was the preferred feed. Instead, the pigs had likely been raised locally. “Evidence of rice husks means the pigs were consuming rice grains,” says Wang, “but the presence of rice leaf phytoliths is really interesting, because that means there had to be rice plants available in the area.” Indeed, the researchers found newspaper reports from the early 1900s of rice farms in the Sacramento Valley owned by Chinese people. “There seems to have been an interesting social network here, with Chinese people farming rice in other parts of California, and the byproducts of rice farming being sent to Chinese households or ranches for feeding pigs,” says Wang.

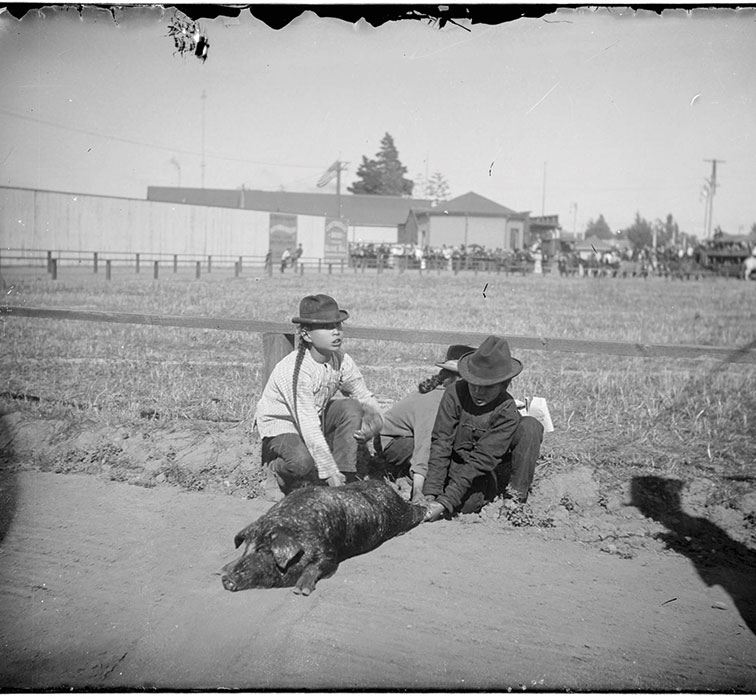

It’s unclear exactly how pigs would have been raised in the heart of Los Angeles. In her research on Chinese Exclusion Act case files, Ng found a 1902 interview in which an employee of one of the Los Angeles Chinatown butcher shops referred to a ranch where another employee slaughtered hogs for the store. In her excavation report, Greenwood says that pigs were commonly raised in whatever space was available—thus, individuals or households may have kept pigs as well. This could explain the presence of roundworm eggs on the pigs’ teeth, which may have resulted from consuming household waste.

When Greenwood’s team cataloged the types of bone they excavated three decades ago, they observed that the meatier cuts of pig were underrepresented. Wang and Ng believe that choice cuts were likely sold at a premium to consumers outside the neighborhood while Chinatown residents ate the less expensive parts. “In Chinese cuisine, we eat all parts of the pig, from the hoofs to the ears,” says Ng, “whereas Euro-Americans, especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, typically ate parts they were familiar with, like pork chops and pork butt.” It seems that Chinese residents found a way to both fill their bellies and line their pocketbooks through rearing pigs. They sourced their feed from Chinese-owned farms, raised the animals on ranches or in backyards, sold the expensive parts to outsiders, and then feasted on the cheaper parts themselves.