One October morning in 336 B.C., the small theater at Aigai, the ceremonial center of ancient Macedonia, began to fill with honored guests. They had come from across Greece and the Balkans to attend the wedding celebrations of King Philip II’s daughter. A day of entertainment was to follow the wedding, and every seat was taken well before dawn. As the sun rose, a royal procession entered. With the atmosphere reaching fever pitch, Philip finally made his entrance. This was meant to be a triumphal moment, the pinnacle of his career. Philip was already the most successful Macedonian king ever. During his 24-year reign, he had invigorated the army, built up the kingdom’s infrastructure, and expanded Macedonian control across the northern Aegean. Now, he was poised to invade Persia. But then, an assassin struck. A rogue bodyguard rushed the king and drove a knife into his chest. Philip fell to the floor, dead. In the tumultuous aftermath, a new king was proclaimed: Philip’s son Alexander. The new king was young, only 20 years old, but he had already led armies and founded his first eponymous city. During his father’s exceptional reign, Alexander had accrued all the skills and experience necessary to make his own mark upon history. He would come to be known as Alexander the Great.

Alexander, who ruled from 336 to 323 B.C., is renowned for his 11-year campaign in Asia, during which he conquered the Persian Empire before dying mysteriously in its capital city of Babylon at the age of just 32. Little is known about Alexander’s early life in Macedonia. Ancient sources provide the story’s bare bones, but a series of archaeological discoveries in northern Greece, which today encompasses the territory of ancient Macedonia, is transforming scholars’ understanding of this kingdom and, with it, the story of the young Alexander.

The capital of ancient Macedonia, and Alexander’s birthplace, was Pella, which now lies many miles inland but was originally a port, connected to the Aegean Sea via a lagoon. Archaeologists have been excavating in Pella since the early twentieth century and have revealed sprawling townhouses, broad avenues, lavish bathhouses, sanctuaries overflowing with offerings, and a huge agora, or marketplace, one of the largest in the ancient world. Some of the richest houses, including the House of Dionysus, were adorned with intricate river-pebble mosaics depicting hunts and mythological scenes. These findings indicate that, at its height, Pella rivaled the grandeur of other great cities of the Hellenistic age (323–31 B.C.)—Alexandria in Egypt, and Pergamon and Antioch in Anatolia, or modern Turkey. But much remained to be discovered.

In 2021, archaeologists from the Ephorate of Antiquities of Pella and the University of Michigan launched the Pella Urban Dynamics Project. Through new surveys and excavations, they hope to further investigate the city’s history and understand how its inhabitants lived. They are also studying Pella’s wider connections. “How did the city work in relation to the larger region?” asks archaeologist and project codirector Lisa Nevett of the University of Michigan. “How did it relate to peer cities with which it was interacting? We’re trying to get away from viewing these places as just sites and see them as cities.”

The majority of Pella’s visible ruins date to the Hellenistic period. A goal of the project is to find evidence of the city dating to the Classical period (480–323 B.C.), the Pella that Alexander would have known. Over the past few years, the team has used geophysics in the hunt for answers. “We started by surveying the area south of the Hellenistic city, where, according to the ancient sources, there was a lagoon or wetlands in the Late Classical period,” says archaeologist and project codirector Elisavet Tsigarida of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Pella. “The results were very good. We’ve been able to reconstruct the south coastline and a small island, Phacos, that was connected to the city by a wooden bridge.” Phacos, according to the Roman historian Livy, was the site of a citadel and treasury. The island was one of Pella’s most recognizable features, and the team believes that the core of the Classical city was located on the mainland facing it. Alexander’s Pella appears to have been small in comparison to its later Hellenistic incarnation and was focused around the waterfront. More than two millennia ago, it would have been alive with the sights and sounds of harbor life—fishers hauling in their daily catch, ships unloading their wares, merchants selling everything from metalwork to wine.

The team has also begun to investigate Pella’s royal palace—Alexander’s likely childhood home. This vast complex, covering nearly 20 acres, was located on a low hill and included numerous buildings terraced into the slope. In 2017, they started to excavate and conserve the buildings. But their work has been far from straightforward. “The poor preservation of the buildings is the biggest challenge,” says Tsigarida. This, she explains, is primarily due to pillaging by the Romans in the second century B.C., the use of the area throughout the Byzantine period, and plunder of buildings in modern times. Despite the state of the ruins, archaeologists have determined that two adjoining courtyard buildings at the center of the complex, both dated to the mid-fourth century B.C., were among the palace’s most important structures. “So far, the project has finished excavating one building where the king received representatives of other cities or states, and where he performed rites for the continuity and well-being of the state,” Tsigarida says. This was also the building where the huge andron, a hall for symposia, or drinking parties, was located and where all royal decisions were made. Excavations are underway in the other courtyard building and in the palace’s palaestra, or exercise yard, where a large swimming pool has recently been discovered. It may soon be possible to walk Pella’s corridors of power, as the young Alexander once did.

Alexander was born in 356 B.C. and grew up in a world that was rapidly changing. His father’s reign, which began in 360 B.C., brought wealth and prestige to Pella. Macedonian kings could be polygamous, and Philip pushed the custom to extremes, taking seven wives in all. Olympias, Alexander’s mother and Philip’s fourth or fifth wife, was a Molossian princess from Epirus in present-day northwestern Greece. Her position in the ultracompetitive royal household relied on Alexander, her only son, remaining the favored heir. Macedonian succession could often be highly contested and depended on who had the strength, experience, and support to seize the opportunity. There were other royal male children, and the prospect that more could be born was ever-present. Philip’s extensive military campaigning also put him at constant risk of death.

The young prince’s education began when he was around the age of seven. He was surrounded by an army of tutors who taught him the Greek staples of reading, writing, music, and athletics. Homer’s epics were already established classics, and Alexander had a special relationship with the Iliad—his mother’s family asserted that they could trace their ancestry back to the Greek hero Achilles. A properly educated Macedonian prince was also required to be proficient with horses, and Alexander became a gifted equestrian. The first-century A.D. biographer Plutarch reports that, on one occasion, when Alexander was 11 or 12, he tamed a stallion called Bucephalus, a feat no one else had accomplished. Philip witnessed this event and, according to Plutarch, responded with the prophetic words, “My boy, you must find a kingdom which is your equal. Macedonia is too small for you.”

A few years later, Alexander embarked on his secondary education. At this time, he likely entered the school of the royal pages, a Macedonian institution that brought aristocratic boys from across the kingdom to court, where they were educated at the state’s expense. (See “Time for School.”) The school was either founded or reformed by Philip and combined liberal studies with intensive military training that aimed to produce men who were of use to king and kingdom. At any one time, there were around 150 boys between 14 and 18 years of age in attendance. During this period in his life, Alexander was tutored for some time by the Greek philosopher Aristotle. In his biography of Alexander, Plutarch writes that their lessons took place at the nymphaeum, or sanctuary of the nymphs, in Mieza, a Macedonian city some 35 miles west of Pella.

The sanctuary was discovered in the 1960s, hidden amid lush vegetation and bordered by a fast-running stream. At the time, it was thought to be the site of the school of the royal pages. The nymphaeum consists of a large outcrop of volcanic rock that was deliberately carved away. There are remnants of a covered walkway, parts of columns, and three natural caves. But, archaeologist Angeliki Kottaridi, director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, is not convinced that the sanctuary functioned as the royal school. “I’m sure you can’t teach, feed, and house 150 students there,” she says. Kottaridi also believes that Alexander’s time at the school was far different from that idealized in the ancient sources. “It’s a very romantic approach to envision Aristotle and his student sitting and discussing metaphysics,” she says. “It wasn’t so. It was a very harsh education intended to produce warriors, and above all to produce officers capable of commanding the army.”

Kottaridi suggests the school may actually have been housed in a massive courtyard building to the northeast. This structure was excavated in the 1980s, and at first, Kottaridi explains, the archaeologists thought they were investigating a sanctuary of Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine. Then, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, researchers thought they were exploring a market, until it came to their attention that they were outside the city limits. “We didn’t find any housing, the theater is there, and we have graves,” Kottaridi says, all indications of a location outside the city walls. She believes this structure is a type of school building known as a gymnasium. The size of the complex, some 500,000 square feet, suggests that it was more than just an exercise facility. Usually situated outside city walls, gymnasiums played a key role in adolescent education in the Greek world—the Academy in Athens, where Plato taught, and the Athenian Lyceum, where Aristotle taught, were public gymnasiums. The Mieza complex includes a grand entranceway, banqueting rooms, and a suite of oblong halls that may have been used as barracks. Based on pottery found at the site and the complex’s architectural style, archaeologists have dated it to the mid-fourth century B.C. and believe it was the setting for Alexander’s time under the tutelage of Aristotle.

Alexander emerged as Philip’s most capable son and was fast-tracked to power. At just 16 years old, in 340 B.C., he was appointed regent, empowering him to rule in Philip’s absence. Around this time, Alexander conducted his first campaign, marching into newly conquered territory in Thrace (modern Bulgaria), where he subdued rebellious natives and founded a city he called Alexandropolis. By age 18, he had established himself in the army and helped his father win a decisive victory over Athens and Thebes at Chaeronea in the Greek region of Boeotia. Two years later, in 336 B.C., he attended his sister’s fateful wedding celebrations at Aigai.

Today, the village of Vergina overlaps the ancient site of Aigai, or the “place of the goats.” Aigai was the first capital of ancient Macedonia and remained an important ceremonial center despite being supplanted by Pella. Less than 10 percent of the site has thus far been excavated, but nevertheless, significant archaeological remains have been uncovered. These include a sprawling prehistoric necropolis, dated to between 1000 and 700 B.C.; clusters of royal tombs, dated to the sixth to third century B.C.; and two sanctuaries, a theater, and a huge royal palace, all dated to the fourth century B.C. The palace has been undergoing large-scale restorations since 2007, and among a host of new revelations emanating from this work is the redating of the complex to Philip’s reign.

The palace is among the largest buildings known from Classical Greece and was designed to impress. At the eastern end, a huge temple-like entrance provided access to a great courtyard, surrounded by columns and lined with grand banqueting rooms. Two of these rooms at the southern end are decorated with pebble mosaics, one depicting a spiraling floral motif, and the other the god Zeus in the guise of a bull abducting the maiden Europa. The western set of rooms is the most expansive in the palace. Its square vestibule, with a five-columned entrance, could seat more than 500 and was perhaps where the king conducted business.

The theater adjoined the palace to the north and it was here that the royal family celebrated in October 336 B.C., until the assassin’s knife cut short the wedding festivities. With Philip dead, an assembly proclaimed Alexander the new Macedonian king. His hold on the throne was tenuous at first. There were divisions in court and among Philip’s allies, and many subjugated peoples were on the verge of rebellion. It was against this uncertain backdrop that the king’s funeral was staged. Ancient sources pass over that event, giving little detail, but nearly a half century ago, it was vividly brought back to life by one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made in Greece.

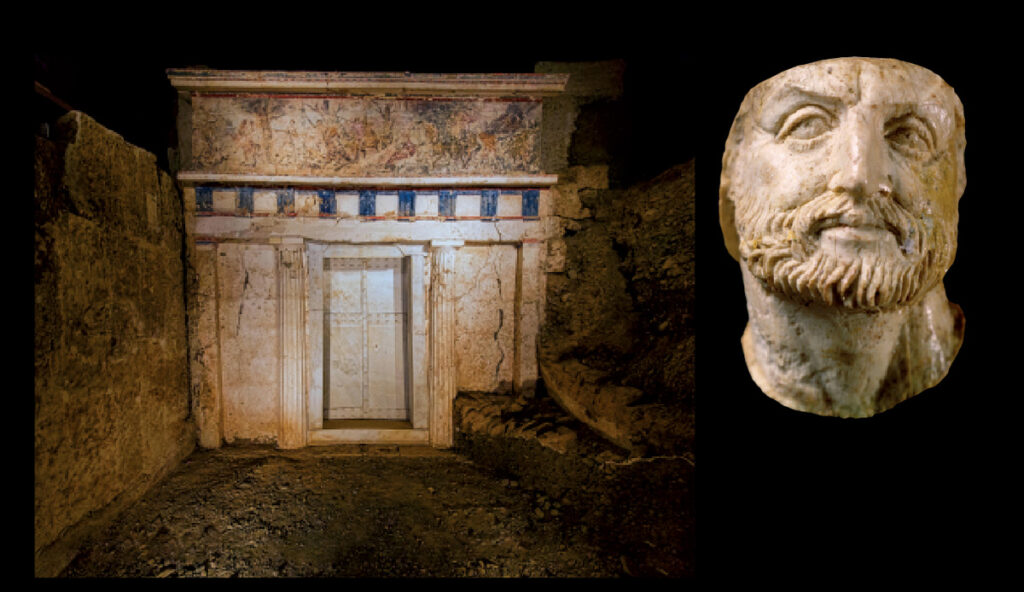

Archaeologist Manolis Andronikos of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki had been investigating the Great Tumulus in Vergina for decades without much to show for it. It was the largest burial mound in the region and its size had proved an obstacle to his investigations. Finally, in fall 1977, with the help of a mechanical digger, Andronikos began to uncover some ancient structures within the mound. Slowly, he revealed a shrine and a box-shaped cist tomb, and then a much larger tomb with a painted facade and masonry burial chamber. Both the shrine and cist tomb had been looted in antiquity, and Andronikos suspected that the larger tomb had suffered the same fate. On November 8, his team lifted a keystone at the back of the barrel-vaulted burial chamber. Andronikos put his head through the small hole and shone a flashlight down onto the tomb’s floor. He saw the glint of silver drinking vessels, the rusted remains of weapons and armor, and, directly below, a small marble sarcophagus. Andronikos was amazed to find that the tomb had never been robbed.

EXPAND

Time for School

Archaeologists opened a window into the lives and appearances of the pages who attended the prestigious royal school of ancient Macedonia during excavations carried out decades ago. On the edge of the Greek village of Agios Athanasios, they discovered a large tomb dating to the last quarter of the fourth century B.C., whose facade is adorned with murals. A painted frieze depicting a drinking party runs along the facade’s upper section. In the image, six men recline on couches, their heads wreathed, a feast laid out before them. They enjoy wine from elaborate drinking vessels and music played by two female courtesans. On the right, several young men arrive at the party. They are attired in the distinctive dress of Macedonian soldiers—a cap called a kausia, a short cloak known as a chlamys, and tough leather boots called krepides. Scholars have identified the young men as either royal pages or new recruits to the army. Flanking the tomb’s door are two more young Macedonians, who stand guard over the dead. Each holds a sarissa, the distinctive type of long spear wielded by the Macedonian infantry, and visibly mourn the deceased. These are images of members of the generation that expanded Macedonian control across the known world under the leadership of Alexander the Great (reigned 336–323 B.C.).

When the sarcophagus was opened, the tomb’s greatest treasure was revealed—a solid gold larnax, or ossuary, emblazoned with a star or sunburst on its lid. Inside the larnax were the cremated remains of the deceased, a large oak and acorn gold wreath folded up and squeezed in beside them. But the finds didn’t end there. The tomb’s antechamber had, until this time, remained sealed. Andronikos removed a block from the partition wall and wriggled through the opening. He was confronted with another sarcophagus. Looking around the chamber he saw additional opulent grave goods, including a golden myrtle-leaf wreath, a pair of gilded greaves, and a golden gorytos, or quiver covering, of a type commonly used by mounted Scythian warriors of the steppe. Inside this second sarcophagus was another, smaller gold larnax. It, too, held cremated human remains, and the gold and purple cloth used to wrap the bones was preserved. There was also an extraordinary golden diadem. The dating of the grave goods to the mid-fourth century B.C. and the size of the tumulus led Andronikos to propose that the tomb belonged to Philip II and one of his wives, a theory that is largely accepted today.

Aside from the golden ossuaries, armor, and wreaths, among the most impressive finds from the site are the remains of the king’s cremation pyre, which were found above the burial chamber. The pyre was monumental, recalling those of Homeric heroes. It contained offerings including food, drink, and sacrificed hunting dogs and horses. The facade of Philip’s tomb was painted a ghostly white, with blue, red, and green highlighting some of its reliefs. Across the upper part of the facade is a large painted frieze depicting a royal hunt. On the far right of the scene, a hunter appears about to thrust his spear at a snarling lion. This is the climax of the action—the lion was the royal quarry—thus, this crucial moment’s relegation to the side of the composition may at first appear strange. However, the identity of a figure who is rushing in on horseback to help explains the scene’s arrangement. This figure wears a purple chiton, or short tunic, and an olive wreath. Scholars believe he is the new king, Alexander, and that the hunting scene is an allegory for his assumption of power, a political statement emphasizing his preparedness to take on the kingship.

In spring 334 B.C., a year after burying Philip, Alexander invaded the Persian Empire, following through on his father’s plans. He defeated King Darius III (reigned 336–330 B.C.) in a series of battles and assumed rule over Darius’ former territory. In order to secure his newly won empire, Alexander campaigned in modern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Pakistan, where his faithful horse Bucephalus died. Alexander built a city around the horse’s tomb, naming it Alexandria Bucephala. By the summer of 323 B.C., Alexander was in Babylon planning further conquests when he suddenly became sick and died. He had designated no heir, and when his companions asked to whom he had left his empire, he replied with his final breath, “To the strongest.”