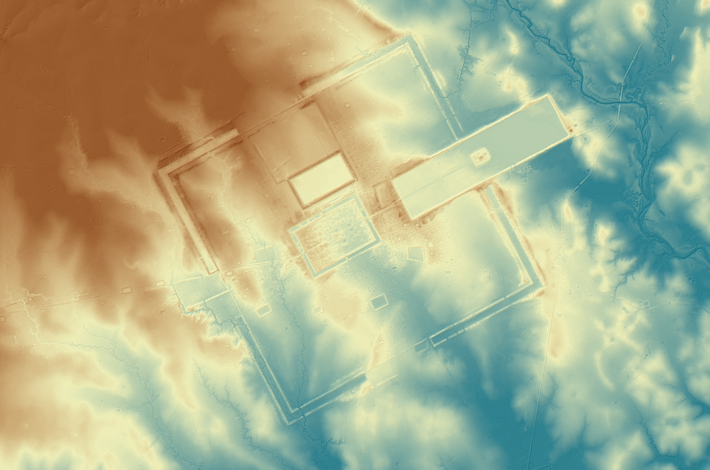

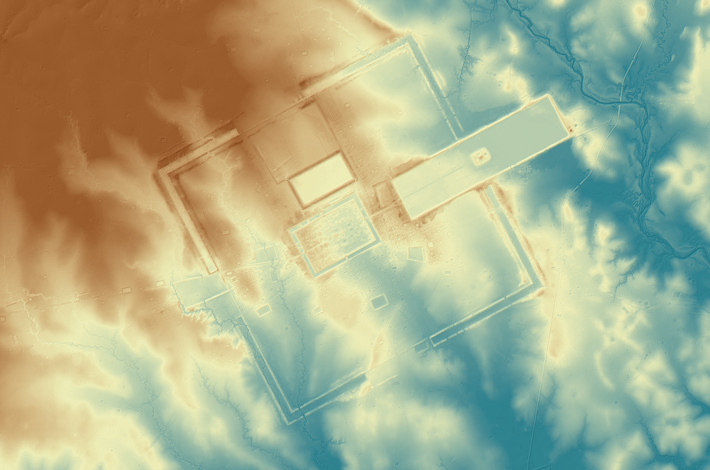

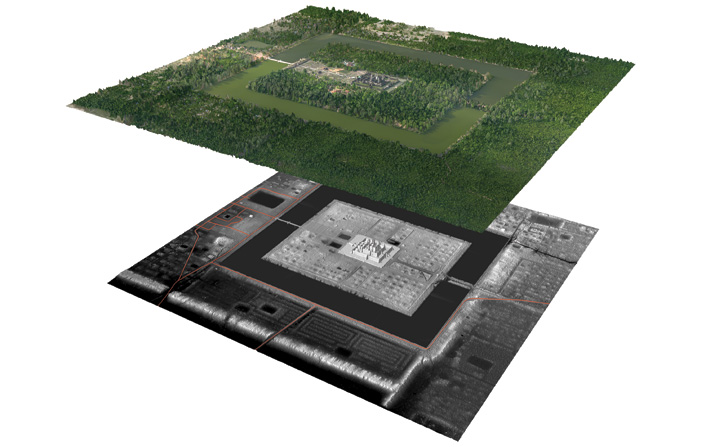

Airborne laser sensing peered beneath vast stretches of centuries-old tree cover to reshape archaeologists’ understanding of the ancient Angkor region, once the epicenter of the Khmer Empire. Previously, scholars believed Khmer cities and temple complexes were enclosed spaces with walls or moats surrounding gridded “downtowns.”

Using lidar, a team led by Damian Evans, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Sydney, showed that these grids extended beyond the fortifications, creating much bigger urban landscapes. For instance, the mapping project turned up evidence of urbanization on both sides of Angkor Wat’s famed moat. Meanwhile, the twelfth-century A.D. Khmer capital Angkor Thom has now quadrupled in size. Imaging showed that its city-block structure extended far beyond the three-and-a-half square miles contained within its walls. It actually encompass more than 13 square miles of formally planned urban space, including within it Angkor Wat, which predated Angkor Thom by 100 years and sits a mile south of the city’s center.

The findings lend support to the theory that Angkor fell because it grew beyond its means. “What you have is an urban structure that is analogous to the giant, low-density megacities that have developed in the twentieth century with the advent of the car,” Evans explains, “a dense urban core surrounded by a vast lower-density periphery, or ‘sprawl.’”