The 1996 discovery of the 9,000-year-old remains of a hunter—known as Kennewick Man—near the Washington-Oregon border presented an intriguing puzzle to archaeologists studying the peopling of the Americas. While he was clearly an early American, he had a larger skull and a narrower face that projected farther forward than those of modern Native Americans. These physical discrepancies led scientists to question whether he was a direct ancestor of modern Native Americans, or if a different group of people migrated to the Americas and gave rise to them.

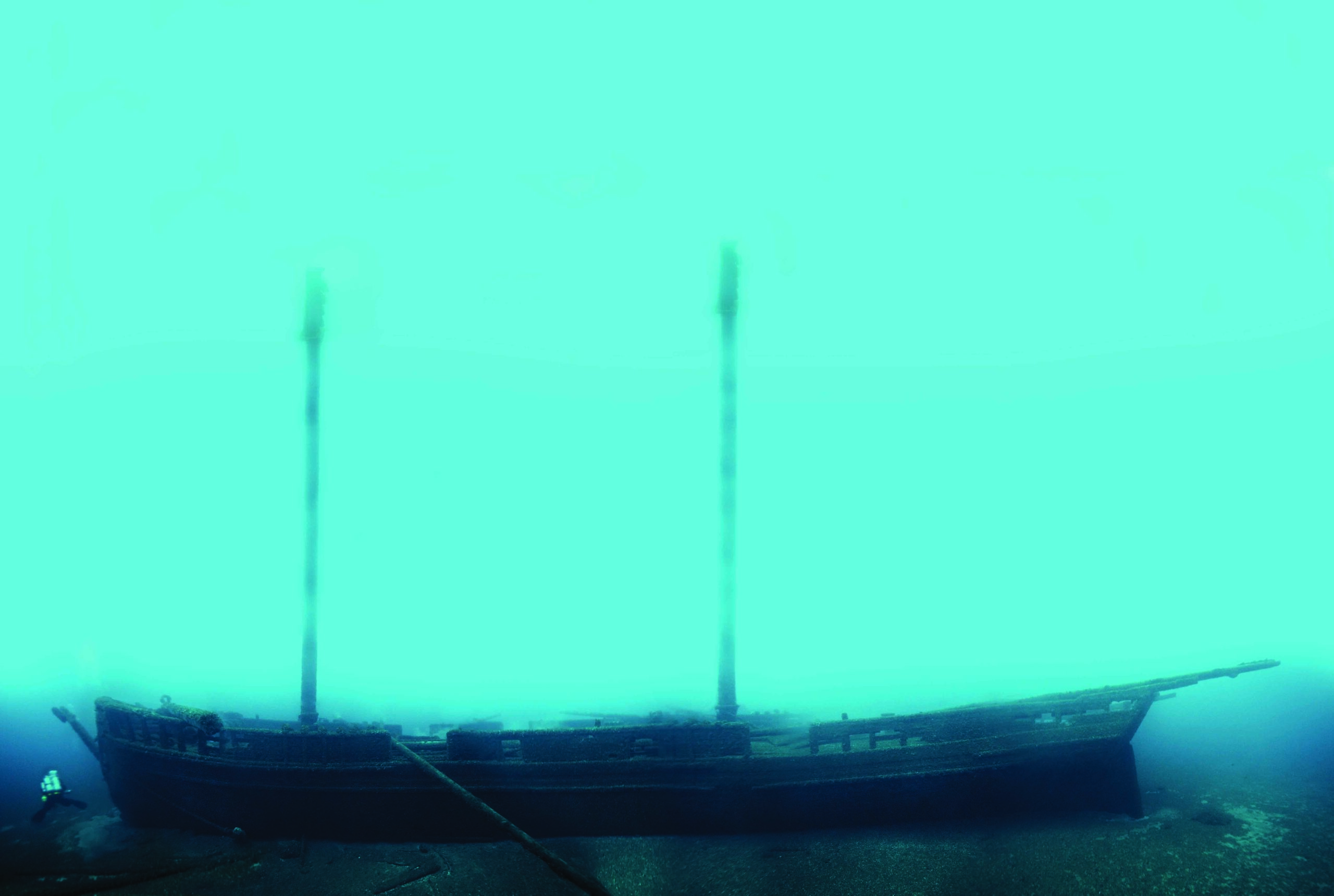

An answer might have been found in a 150-foot-deep water-filled trench known as Hoyo Negro (“black hole”) in an underwater cave system in Mexico’s Yucatán. There, in 2007, divers found the nearly intact skeleton of a 15- to 16-year-old girl they called Naia (for the Greek water nymph). This year, scientists announced what Naia’s remains revealed.

Multiple methods used to date her teeth and bones suggests that she lived between 12,000 and 13,000 years ago, making her one of the earliest humans ever found in the Americas. Analysis of her mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mother to child, show that she had a constellation of genes that is common among modern Native Americans. Her skull construction is also similar to that of Kennewick Man.

“She has the physical characteristics we expect to see in Paleoamericans, and the genetics say she and modern Native Americans share ancestry,” says James Chatters, an archaeologist who has studied both Naia and Kennewick Man.

These two ancient Americans—and modern Native Americans—can likely all trace their heritage back to the same source population, a group that is thought to have been isolated for thousands of years in Beringia, the land mass that once connected Asia and the Americas. Researchers now believe that adaptations over the past 13,000 years in the Americas produced changes in appearance, leading to the features we commonly see among today’s Native Americans.