If every home tells a story, then Knole House is a tome. By any measure one of the five largest houses in England, this country estate in Sevenoaks in west Kent has seen six centuries of British history, and the reigns of some 30 monarchs. Knole House has been the backdrop for all the ups and downs of the English aristocracy and for the lives of the countless tradesmen, butlers, maids, cooks, and footmen who kept dwellings like it running.

Located just 30 miles outside London, the house occupies four acres, surrounded by 26 acres of gardens and fields, and another thousand that make up a medieval deer park. If the house sprawls, it is with good reason. From Sir James Fiennes to the Archbishop of Canterbury to King Henry VIII to many generations of the Sackville family, each new owner has added to its size and complexity, which has resulted in a multilevel labyrinth. It is difficult even to get an accurate count of all the rooms—the best estimate is around 420, connected to courtyards, staircases, attics, and seemingly miles upon miles of corridors. “Knole has almost always had too many rooms,” says archaeologist Matthew Champion. “Each owner kept adding to it to increase their status, but they could never keep on top of using them all.”

Vita Sackville-West, the early-twentieth-century writer and inspiration for Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, grew up in the home and described it as resembling “a medieval village with its square turrets and its grey walls, its hundred chimneys sending blue threads up into the air.” Today, one wing is occupied by Robert Sackville-West, 7th Baron Sackville, and his family, but the house is owned and managed by the National Trust, to whom it was donated in 1947 by the 4th Baron, Charles. Supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Trust is conducting a major five-year program of restoration that is offering an unprecedented look at the house and grounds, its construction, and the lives of many of those who passed through its halls.

The project involves lifting floorboards, inspecting rafters, and repointing walls—an excavation of the house itself. Archaeologists have found, behind the walls and across the gardens, stories of the house’s occupants and employees, stories that reflect the changing moods of the country through time: the economic impact of the War of the Roses, the paranoia following the Gunpowder Plot, England’s obsession with sport, the arrival of modern technology—and, of course, generations of family intrigue.

The history of the site of Knole House goes back to well before the first block of dark-gray local Kentish ragstone was laid in 1445. Within the parkland around the estate are what appear to be the remnants of Bronze Age fields, patterns of irregular plots around one acre in size, according to Al Oswald, a landscape archaeologist from the University of Sheffield. A low hill in front of the house, called Echo Mount, may even be topped by a Bronze Age burial mound. “There’s been lots of speculation about which ‘knoll’ the place name refers to,” says Oswald. “I just wonder if this burial mound is the knoll, the local landmark, from which the house took its name.

Next to Knole and thought to predate the house is a whopping great medieval stone barn, some 30 feet tall, enclosing an area the size of two tennis courts, that shows off the size of Knole’s agricultural estate even before there was a manor house to boast of. In the surrounding parkland, Oswald has also found “lynchets,” or terraces formed by plowed soil. The fields likely date to the same time as the barn, but wouldn’t have provided anywhere near enough grain to fill it. “It suggests that the barn was used to gather the harvest from a much wider area,” says Oswald. The estate appears to have already been productive when Sir James Fiennes, swashbuckling soldier and cunning politician (and distant ancestor of English adventurer Ranulph Fiennes), began to build a house in 1445 as a way to spend his ill-gotten spoil from the Hundred Years War. Alas, he was beheaded before he could finish the house, and his son sold it in 1456 to Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury, who completed the building works.

The archaeologists and architectural historians working on the house have found, to their delight and surprise, that much of Bourchier’s original structure survives. “The original building has been swamped and swallowed up by accretions, but it is still there,” says James Wright, a buildings archaeologist from Museum of London Archaeology.

Documentary evidence records that the Pheasant Court building, named for the small courtyard adjacent to it, is one of the oldest structures in Knole House, and that the Chapel adjacent to it was built in 1460. Wright was able to confirm this when he discovered a decorative molded gable at the end of the Pheasant Court building that had been obscured by the later construction of the Chapel. Dating of the timbers reveals that Bourchier, a staunch Yorkist in the War of the Roses, halted construction on the house between 1460 and 1461. “This period coincides with when the Yorkists were losing the battle,” says Wright, “and the rapid extensions from 1461 onwards fit with when they were winning the war.”

Such older portions of the house display a number of unusual building techniques. For example, most English buildings of the period used “jowl posts,” or posts that balloon out at the top to support the weight of the roof. In the East Range of the house, which dates back to the early sixteenth century, after Bourchier had died and bequeathed it to the See of Canterbury, Wright found no evidence of jowl posts. Equally puzzling were the unusual decorative molded timbers, each hewn from a single hunk of oak, providing structural support at either side of the windows. “Time and again we find unconventional and sometimes questionable techniques in use at Knole,” he says, “which is surprising for such a high-status house.”

That status only increased with time, as, in 1538, King Henry VIII claimed the house as a royal country palace. The monarch is known to have been a designer and architect in his own right, and there is debate about how much input he had at Knole. Circumstantial evidence, such as the style of the architecture, hints that he might have been responsible for adding a new range to form a courtyard, the Green Court, in front of the original house, but there is little supporting documentary evidence for this. The house passed through various hands connected to Henry VIII’s successors until 1566, when Queen Elizabeth I granted freehold of the estate to her cousin, Thomas Sackville.

Between 1566 and 1604, Sackville could not afford to live in the house, so it was leased out. It is during this period that archaeologists believe another feature, the manor’s 26-acre walled garden, began to take shape. It was long thought that the layout of the garden was the result of careful planning. According to documentary sources, one of the lease-holders in this period, John Lennard, built the first garden wall in 1574 to protect four freshwater springs supplying the house. However, landscape archaeologist Oswald’s analysis of the garden’s features suggests an even more pragmatic explanation.

The far end of the walled garden, known as “The Wilderness,” has been densely wooded for the last 200 years, though it was once formal orchards. Curving paths lead visitors into the woodland, past the springs, by a sunken garden (once the site of an ornamental canal), and along an embanked avenue known as Causeway Walk. The woodland also conceals an irregular hollow in the ground, around five acres in size and up to 12 feet deep. It was assumed that all these features had been carefully designed. Oswald studied changes in soil type and the lay of the land, and now believes that the hollow was originally a sand quarry, likely for glassmaking, which Lennard is known to have done. The springs may have emerged when quarrying penetrated the water table, he thinks, and the canal and causeway were later attempts to disguise the eyesore. “The garden gives the impression of a carefully thought-through design, but looking closer shows that in fact it was a bit of a superficial ‘garden makeover,’” he says, “making the best of the industrial mess the Sackvilles inherited.

By 1604, the fortunes of Thomas Sackville, English statesman and Lord High Treasurer, had improved. He bought out the Knole lease from Lennard’s son, and his family has lived there ever since. Like all the previous owners of the house, the Sackvilles continued to build onto the manor and shape the grounds. Some of these changes began immediately, including the construction of a suite of rooms, the King’s Rooms, that are thought to have been prepared specially for a visit from King James I, a visit that never occurred. The current restoration effort has looked closely at the Upper King’s Room, peeking behind walls, under floorboards, and above ceilings. There, Wright came across a series of strange patterns inscribed into the floor joists and around the fireplace, including burn marks, cross-hatch patterns, and W-shaped symbols that symbolize the “virgin of virgins,” or the Virgin Mary. These are known as apotropaic marks, also called “witchmarks” or “demon traps,” placed there to protect the occupant from sorcery or possession.

The direction of the burn marks shows that the symbols were placed before the timber was laid, and tree-ring analysis dates the timbers to between 1605 and 1606—around the time of the Gunpowder Plot, when conspirators (including Guy Fawkes) attempted to blow up Parliament and kill King James I. According to Wright, “These marks give us an insight into the mindset of ordinary people at that time,” a time of suspicion and even hysteria.

But times eventually calmed, and the succession of Sackvilles who inherited the house—all men, as specified in Thomas’ will—sometimes had more leisurely pursuits on their minds. Oswald spotted one of these interventions while walking through the parkland on a winter’s day, when a line of unmelted frost indicated a low embankment running parallel to the front of the house. He followed and mapped the feature and found that there had once been perfectly square, leveled lawns flanking a drive to the Outer Wicket Tower, a later addition that served as gatehouse to the Green Court.

In historical records, Oswald found a note of a payment to three laborers in 1612, for “beating & rowling the green before the gate to make it even,” suggesting the leveled area was a pair of bowling greens. Interestingly, they strongly echo the symmetrical bowling greens laid out by previous Knole House owner King Henry VIII in front of the only palace he designed and built from scratch: Nonsuch, in Surrey. Perhaps the hand of that royal designer was responsible for these as well. “I love the fact that these slight, grassy humps and bumps can tell us things about the building that the building itself can’t tell us,” says Oswald. “In this case we can see that the bowling greens match the extent of the Green Court [that may have been designed by the king] and echo Henry’s work at Nonsuch.”

A century later, another sporting feature came into shape. In the parkland northeast of the house is Knole’s private cricket pitch. Oswald believes it may be the oldest purpose-built cricket ground in England. Until now it has been assumed that the Vine cricket pitch in Sevenoaks, on what was once a Knole estate vineyard, was England’s oldest, with the earliest documented match occurring in 1734. But Oswald has found circumstantial evidence to suggest that a pair of cricket-mad Sackville brothers—Charles and John—may have honed their skills closer to home. “We know that this area was plowed during the food shortages of the English Civil Wars in the later seventeenth century, and we have a fleeting reference to the deliberate leveling of the plow ridges in 1720,” says Oswald. “For what purpose, if not the creation of the cricket pitch?

Any estate of the size and complexity of Knole House needs more than owners to keep it running. An army of servants, groundskeepers, housemaids, craftsmen, and more lived and worked in and around the house. While most of the remains in the house reflect the desires and tastes of its owners, others who spent their lives in service of Knole left evidence of their presence too. Long, narrow, dusty attics span the breadth of the house (about the length of a bowling lane), and archaeologist and graffiti expert Matthew Champion has found vast collections of graffiti scrawled there, on walls, rafters, and eaves.

Most of the graffiti currently visible begins around 1890—when the walls were last given a coat of limewash. But it is clear, Champion says, that the practice goes back much further. “We have found some earlier inscriptions in places that missed the 1890 limewash, including one dating to 1758,” he says. They run from the personal to the purely utilitarian. For example, Eileen Joyce Knight, an underhousemaid in the 1940s, had the habit of declaring her presence by writing her name in a variety of locations.

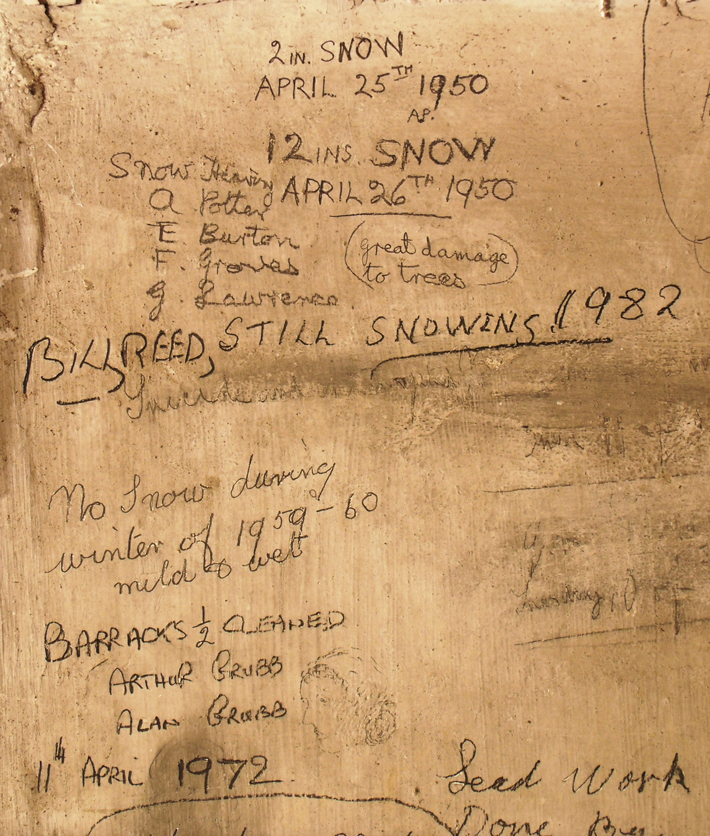

Elsewhere, above part of the house known as the South Barracks, rain drains off the roof via a series of internal gutters. Snowmelt can make the gutters overflow, causing water to pour down into a gallery room below. To prevent flooding, servants were sent up to clear snow from the roof. On the wall in the associated attic area, those servants made a complete record of snowfall from the 1890s to the 1990s, including date and depth.

In other cases, the walls served as a kind of notepad, where workers jotted down what they were doing. One inscription reads, “Temprey Gasspipe for Grate Hall Hunt Ball January 6th 1895.” “It tells us about the technology being used at Knole and the importance of these social events,” says Champion. “Weeks and weeks of preparation, installing a temporary gas supply to power gas lights, just for one evening!”

In other places, carpenter’s marks are visible, sometimes in a way that reflects the fortunes of the Sackvilles, which rose and fell as is common among such old families. Wright examined roof timbers on the eastern side of the house and saw unusual patterns. “We found that the carpenter’s marks—the numbers that carpenters scored into the timbers to remind them which piece went where—are all out of sequence,” he explains. The timbers are, surprisingly, a hodgepodge recycled from at least five different earlier roofs. During the eighteenth century, when these changes were made, there was likely some financial need to reuse older materials.

The twentieth century brought a great deal of change to the English nobility, and the Sackvilles, by then the Sackville-Wests, were no exception. They are not a direct inspiration for the fictional Crawley family of Downton Abbey, but their scandals, dramas, and angst should be familiar to viewers of the show. The 2nd Baron Sackville, Lionel, for example, fathered seven children with a married Spanish dancer, Josefa de la Oliva, known as Pepita. One of these sons claimed to be the rightful heir, but was denied by the courts, and ownership of Knole passed to another Lionel, a nephew. This Lionel, in turn, married his first cousin, Victoria, another of the 2nd Baron’s children with Pepita. Their only child was Vita Sackville-West, famed writer affiliated with the Bloomsbury Group, who wrote Knole and the Sackvilles about the experience of growing up there. She, of course, couldn’t inherit the estate, so it passed to her uncle Charles, who made the gift of Knole House to the National Trust. Then, in 1962, his son Edward, known as Eddy, became 5th Baron Sackville.<

In 1925, the notably rather eccentric Eddy had been given a suite of rooms in the Outer Wicket Tower, thought to have been built in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. Eddy was musically gifted as a child and became a noted music critic (and middling novelist) and proponent of British composers. Up a steep set of spiral stairs, in the music room of the Outer Wicket Tower, which would have contained Eddy’s Steinway baby grand piano, faint marks on the walls indicate the site of a significant set of shelves. “The spacing and arrangement of the shelves suggest that they were specially designed to house his extensive gramophone record collection,” says Vicky Patient, a research volunteer. Eddy is credited with helping to found BBC Radio 3, the United Kingdom’s premier classical music radio station.

Vita remained bitter that she had no claim as heir to Knole, and described Eddy “as floppy as an unstaked delphinium in a gale.” Peeling paintwork, in “Bloomsbury set” colors, including dusky pink, striking turquoise blue, and pale sea green, in his private suite, would have been chosen by Eddy himself. “We’ve been able to date the paintwork by looking behind the electrical wiring,” explains Knole curator Emma Slocombe. “We know that Knole had electricity installed in 1906.”

Following Eddy’s death as a bachelor in 1965, another cousin named Lionel became 6th Baron. He presided over a major restoration of the grounds following a disastrous storm in 1987, and had five daughters. Again the house passed by them to a cousin, Robert, the current Baron Sackville, a publisher and author of two additional books about the family and home. He lives in a portion of the house that is not open to the public and, unlike several of the Barons, has a son. Britain has been a busy place for thousands of years, and much of its history has been lost as stones are reused, fields plowed, and housing estates and industrial complexes built. There are only a few places like Knole, from the ancient paths that still crisscross the estate to the hidden stories behind its walls, where history accretes, layer upon layer, generation upon generation. And surprising even to the archaeologists is the breadth of the memories these stately homes can store, from the impacts of world-changing events and social shifts to the details of the lives of the house’s illustrious occupants to the rarer remnants left by ordinary, oft-unheard servants.

Slideshow: England's Grand Estate

Knole House, in Sevenoaks, Kent, is one of the largest homes in England, and has been witness to six centuries of British history. The National Trust is currently conducting a major five-year program of restoration that is offering an unprecedented look at the house and grounds, and glimpses into the lives of many who passed through its halls—from aristocrats and eccentrics to footmen and housemaids. Each owner of the house, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, King Henry VIII, and many generations of the Sackville family, has added to its size and complexity. The new project, which involves lifting floorboards, inspecting rafters, and repointing walls, is like an excavation of the house itself. While Knole House wasn’t a direct inspiration for Downtown Abbey, its architecture and the dramas of the Sackville family will be familiar to fans of the show. Below is a slideshow of images that illuminate the history of this majestic home.