On a balmy July afternoon, archaeologist Roos van Oosten strides through a muddied plot of land near the center of the Dutch city of Leiden and takes an exploratory sniff. The plot, bordered on all sides by apartment buildings, will soon be part of a housing development known as the Meelfabriek, but, for now, van Oosten and a team of excavators from RAAP Archaeological Consultancy are studying the remnants of a 400-year-old neighborhood.

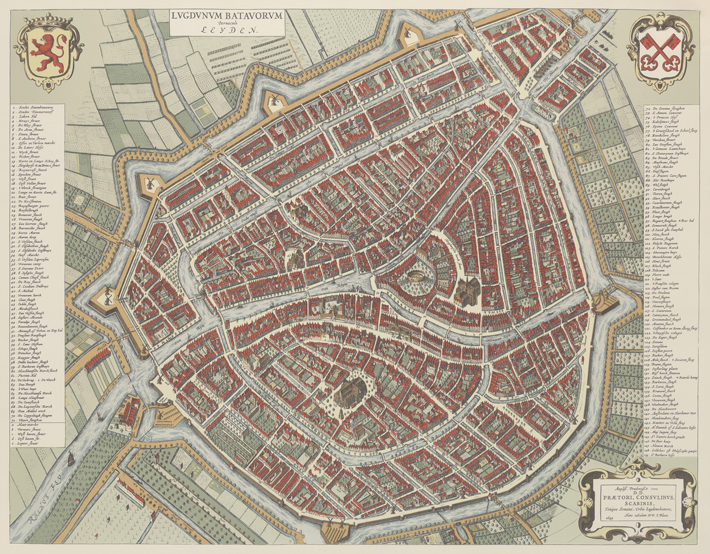

With another sniff, van Oosten gestures to a brick-lined pipe, half obscured with mud. A backhoe rumbles to life and swings its toothed bucket down on the pipe, cracking it open. It is a sewer. Exposed to all present is a stew of squelching, midnight-black muck—excrement that has been brewing for four centuries. Released into the air is an eye-watering aroma, a smell so concentrated and forceful it seems to take shape as a cloud. The excavators stagger back a step, turning their cheeks as though they’ve been slapped. Van Oosten peers down into the muck, and, with a lilt in her voice, says, “Jackpot!” She scribbles notes on a small pad. From her backpack she pulls a laminated map of Leiden showing the layout of the walled city in the mid-seventeenth century. She moves her finger across the map, following the route of the sewer pipe.

Van Oosten is a connoisseur of muck. She has spent the last decade sifting through the cesspits and sewers of medieval European cities, studying how people of the late Middle Ages managed their waste. In society’s relationship to its so-called “foul matter,” she has uncovered surprisingly intimate details of medieval life. In long-overlooked municipal archives on sanitary infrastructure, she has tapped into civic attitudes to dirt and waste. With a latrine’s-eye view of history, van Oosten, along with other scholars, is now challenging the popular vision that the streets of late medieval Leiden—or London, or Paris, or Bruges, or any other sizable city of the time—were dark, gloomy quagmires. In fact, van Oosten says, the humble brick cesspits that characterized urban medieval life in cities such as Leiden were relatively hygienic. It wasn’t until cesspits gave way to sewer-based infrastructure in the early modern era that the relationship between the citizens of Leiden and their waste turned truly foul.

Today, Leiden is a small, placid city of 125,000, where rows of narrow, ivy-covered townhouses line a jigsaw of canals. Situated near the North Sea between The Hague and Amsterdam, it is home to the oldest university in the Netherlands—Leiden University—where researchers have made some of the greatest discoveries of modern science, from the recognition of the Big Bang to the concept of superconductivity. It’s a place that has been featured in documentaries about urban planning and efficient infrastructure, where unhurried cyclists glide back and forth over bridges, and boaters on the canals stop to enjoy dockside picnics.

While the excavators sift through the muck at the Meelfabriek in search of artifacts, van Oosten pedals her bicycle through the streets of the city. As she rides over the cobblestones, she points out vestiges of medieval Leiden that have survived the intervening centuries. Leiden was once a hub of the textile industry, she explains, a place where fabric of all types was processed and then distributed throughout Europe. Down one passage, lining the shaded bank of a canal, were the homes of spinners, weavers, and tuckers, the artisans who manufactured the textiles. Down another street was the Laecken-Halle—the “Cloth Hall”—the guild house of the wool merchants, where fabric was inspected before being put to market. The medieval city, she says, was a bustling place, far denser than it is today, where neighbors were living one on top of the other.

When van Oosten first arrived at Leiden University in 1998 to embark on an undergraduate degree in archaeology, she carried a mental image of medieval urban life that is widely held in contemporary culture. “Most people think of cities of the time as chaotic, dirty, and full of disease,” she says. “It’s the stereotype of the ‘urban graveyard.’” This is a vision largely created by Victorian-era authors, who were writing on the heels of the Industrial Revolution. To take one example among many, nineteenth-century antiquarian Augustus Jessopp, an authority on the Middle Ages at the time, described life within the walls of a medieval city as “a dense slough of stagnant misery, squalor, famine, loathsome disease, and dull despair” where the inhabitants “quietly rotted and died.” The physician George Newman, a contemporary of Jessopp’s, described “a society that knew little of decency, cleanliness, and order,” which was characterized by “total neglect of all hygienic or sanitary laws.” The Victorians gave root to a very specific image of late medieval urban life. Cities were cast as brutish, uncivilized places, ruled by negligent governments entirely indifferent to the health and well-being of their citizens. Butchers tossed entrails and offal into the street. People emptied buckets of excrement out of their windows. City dwellers were said to have trudged to market through drifts of rat-infested garbage and waded through rivers of their neighbors’ feces. Few people bathed, of course, as everyone lived in ignorance of or indifference to their own stench. In Victorian descriptions of the time, medieval life was an altogether precarious ordeal, where people lived forever a sneeze away from death.

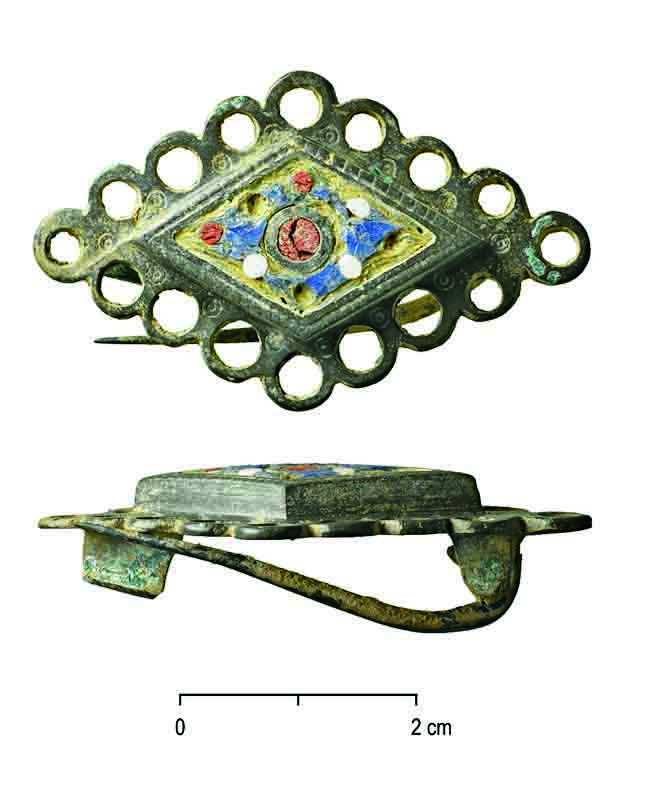

It was when van Oosten began her research on waste that her vision of medieval cities underwent a shift. It began more or less by accident, when she was a graduate student and writing her dissertation on Dutch ceramics such as cooking pots and water jugs. In searching for the best-preserved artifacts, she found that city dwellers would often discard their old kitchenware in the household cesspit—the underground privy located in the backyard of a private home—where it would be mixed in with the family’s communal muck. She spent many hours studying the artifacts dredged up from cesspits. “The boggy environment,” she says, “provided the perfect conditions for preservation.” This allowed her to study centuries-old ceramics that looked like they had been made the day before.

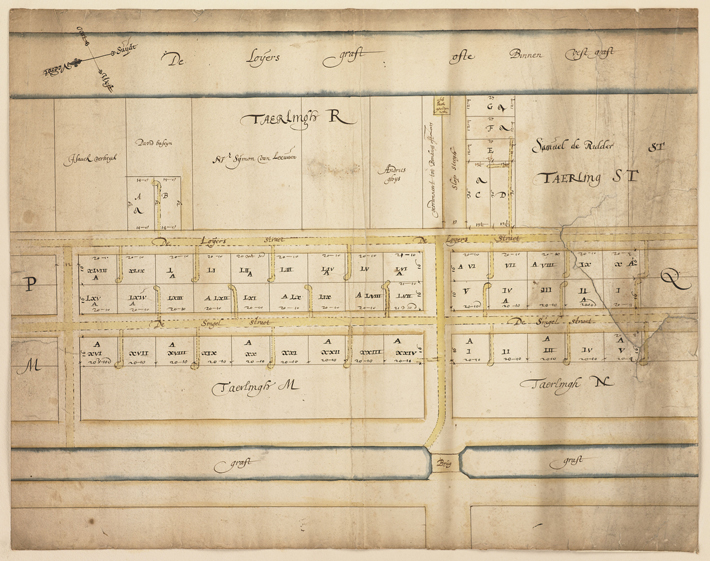

Over the years, she studied dozens of cesspits in Leiden and dozens more in surrounding cities such as Haarlem. She learned that in the fourteenth century, when regular plots for house construction were first established, cesspits were introduced to these cities in large numbers. In fact, in Dutch urban excavations, archaeologists find cesspits in nearly every plot. As she spent more time examining these sunken brick pits and documenting their contents, she became less interested in the ceramics they contained and more interested in how people of the Middle Ages thought about the cesspits, how they fit into the daily life of the city. She saw that cesspits and other sanitary infrastructure opened an unexpected window into how cities governed themselves.

Not far from the Castle of Leiden, a rounded stone structure erected in the eleventh century, van Oosten locks up her bike and heads into a stately brick building that holds the city’s archives. In a hushed room, surrounded by scholars cloistered in study carrels, she lays out a series of pamphlets on a table, each of them centuries old, yellowed and brittle at the edges. They bear such names as “Inspection of the Ordinances on the Subject of Privies” and “Rules and Orders on Privy-Cleaners and Nightworkers.” By examining documents such as these and amassing a large database of excavated cesspits—104 from Leiden alone—van Oosten has been able to reconstruct the intricacies of waste management in vivid detail.

In the archives for an almshouse in Leiden called Sint Agnietenhof, she discovered 34 written permits, each of which describes the cleaning out of a private cesspit by a team of nightmen. The 400-year-old paper trail reveals a fastidious process, each step of which was administered with precision. On September 20, 1603, she reads, in the backyard of a small house on the Rapenburg Canal in the center of the city, a nightman named Baernt Robberechtsz removed 95 tubs of waste from the cesspit of an aging widow by the name of Sara de Haen. According to city regulations, Robberechtsz and his team would have guided their barge into the city after 10 p.m., so as not to offend the sensibilities of the citizenry. Upon mooring at the bank of a canal, the nightmen proceeded to the backyard of Sara de Haen’s home. The “hole-man” climbed down into the privy and scooped out waste—known as “night soil”—which two men on the surface transferred to a wooden tub or barrel. The “tub-men” then undertook the task of carrying the vessel and its sloshing contents back to the barge. Robberechtsz and his crew followed a path through the streets and alleys so exact that their salary was calculated according to how many steps they took. Finally, the crew entered the barge by way of a gangplank and by the light of an oil lantern in order to prevent any spillage in the river. And they did so quietly—if the nightmen were loud, drunk, or sloppy with the night soil, they could be prosecuted. Records show that unscrupulous nightmen in Leiden were punished on at least two occasions. Upon completing the job, before they could be paid, their supervisor checked the cesspit to make sure it had been properly emptied. Even centuries later, it is clear that such punctilious lawmaking and record keeping were not the work of a society ignorant of decency, cleanliness, and order.

As it turns out, archives all over Europe hold documents that reveal long-ignored systems of public health and hygiene. In cities throughout the Netherlands, going back as far as the thirteenth century, so-called mud officials patrolled the streets, doling out fines to citizens who disposed of their waste inappropriately. Other cities benefited from the services of “waste citizens,” who were enlisted to clean specific places in the city in exchange for citizenship. The Belgian city of Antwerp employed men who monitored the city’s freshwater supply, while a brigade of “dung carriers” (moosmeiers) in Bruges removed waste from cesspits to beyond the boundaries of the city. London was voided of its waste each night by so-called gong farmers.

The city of Ghent—one of the larger urban centers of the late medieval period, with a population of 40,000 by the seventeenth century—employed an especially versatile sanitary official known as the “King of Dirt.” As decreed by the city, the King of Dirt, along with a group of underlings known as the “King’s Children,” would patrol the city, punishing citizens for unsanitary behavior. City logs show that one Janne Lanenman held the office of King of Dirt between 1339 and 1348. Clad in a striped yellow tunic—the position’s standard uniform—he and his minions were responsible for chasing vagrant pigs out of the street and doling out stiff fines to their owners, ensuring that butchers correctly disposed of carcasses, hunting down the source of wayward and noxious aromas, and shooing prostitutes from the city square after sundown. University of Amsterdam historian Janna Coomans has studied the position of the King of Dirt and says that the office demonstrates “a sense of civic responsibility. It shows that there were systems in place to clean waste, that it was not chaos.”

As evening approaches, van Oosten emerges from the archives, unlocks her bike and begins walking along a canal bank toward the city center. Baskets attached to a row of iron streetlamps spill over with bright red geraniums. She peers down at a cluster of lily pads bobbing in the water of the canal at her feet. Today, the canals of Leiden are clean, models of the modern Dutch commitment to water quality, but at the end of the medieval period, they turned toxic.

The sewer pipe van Oosten saw cracked open at the Meelfabriek site helps explain how this happened. The excavation there exposes a moment in the history of Leiden when the city shifted away from the cesspit system. In the early seventeenth century, at the behest of the dominant, expansion-minded textile barons, officials began to install brick sewer infrastructure that was much cheaper to maintain than cesspits. Archaeologists have unearthed more than two dozen of these brick sewer lines in Leiden’s city center. They ran from privies in the backyards of houses, down streets, and emptied into canals. The communal sludge that had been so efficiently managed by nightmen was now flowing directly into the city’s stagnant canals. Though this period coincides with the prosperous era known as the “Dutch Golden Age,” public health in Leiden fell off steeply. As city dwellers drank beer brewed with contaminated water, an epidemic broke out: Between June and December of 1669, 40,000 people fell ill and 2,000 people died from what was known at the time as “the fevers,” but was probably cholera, or the “blue death.” It also gave rise to an epic stench. One Leiden resident, Adam Thomasz Verduyn, wrote in 1670 that the installation of sewers had turned his city into a “stinkhole” that reeked like a “common privy.” Van Oosten refers to this as the “Great Dutch Stink.” The Dutch Golden Age, then, not the medieval era, was when Leiden transformed into the foul city of Victorian imagination.

The pattern is thrown into even sharper relief, van Oosten says, when she compares Leiden to the city of Haarlem, where the primary industry was breweries, whose owners were deeply concerned with water quality. Because of this, officials in Haarlem did not fill in their cesspits and replace them with sewer infrastructure. Neither epidemic nor great stink occurred in Haarlem, where the era of cesspits lasted until the nineteenth century.

Van Oosten—along with Coomans and other colleagues—now participates in a multidisciplinary research initiative called Premodern Healthscaping. The project aims to reveal the sophistication of public health and sanitation in late medieval cities. They strive to counter the “smear campaign” carried out by the Victorians on medieval urban life. (The project motto: “Less mud-slinging and more facts.”) Contributors to the effort have archaeologically documented the ubiquity of public baths in late medieval cities, where people of every class came to wash themselves on a regular basis. They have shown that soap-making guilds were part of a booming economy, that late medieval urbanites were lovers of perfume, and that they valued clean teeth. Literary scholars have shown that medieval poets championed the joys of bathing and that knighting ceremonies culminated in scented baths.

None of this is to suggest that any late medieval city was necessarily a paragon of salubriousness, certainly not by today’s standards. A stroll through the center of medieval Leiden, or any other city at the time, would deliver an olfactory experience powerful enough to buckle the knees of most modern people. But life in these cities transcended hygienic unpleasantries. “It’s not that there wasn’t disease and dirt,” says van Oosten. “But cities weren’t disorganized, they weren’t urban graveyards. People weren’t indifferent. They cared about their environment.”