In 1976, paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey discovered the oldest known hominin footprints. The footprints, in Laetoli, Tanzania, have been dated to around 3.66 million years ago and are thought to have been left by members of the species Australopithecus afarensis. They consist of two parallel tracks: undisturbed prints from a single individual and a set of overlapping prints from at least two ancient primates.

In the decades since the discovery, attention has focused on the undisturbed prints, in part because the overlapping ones have been considered too fragmentary to study. Experts have estimated that the individual who left the undisturbed prints stood just over four feet, three inches, and walked at around 1.4 miles per hour. However, there has been extended debate over how efficiently this individual’s feet worked compared with those of modern humans. Formulating answers to this question has been complicated by the limited sample size—a single track from just one individual.

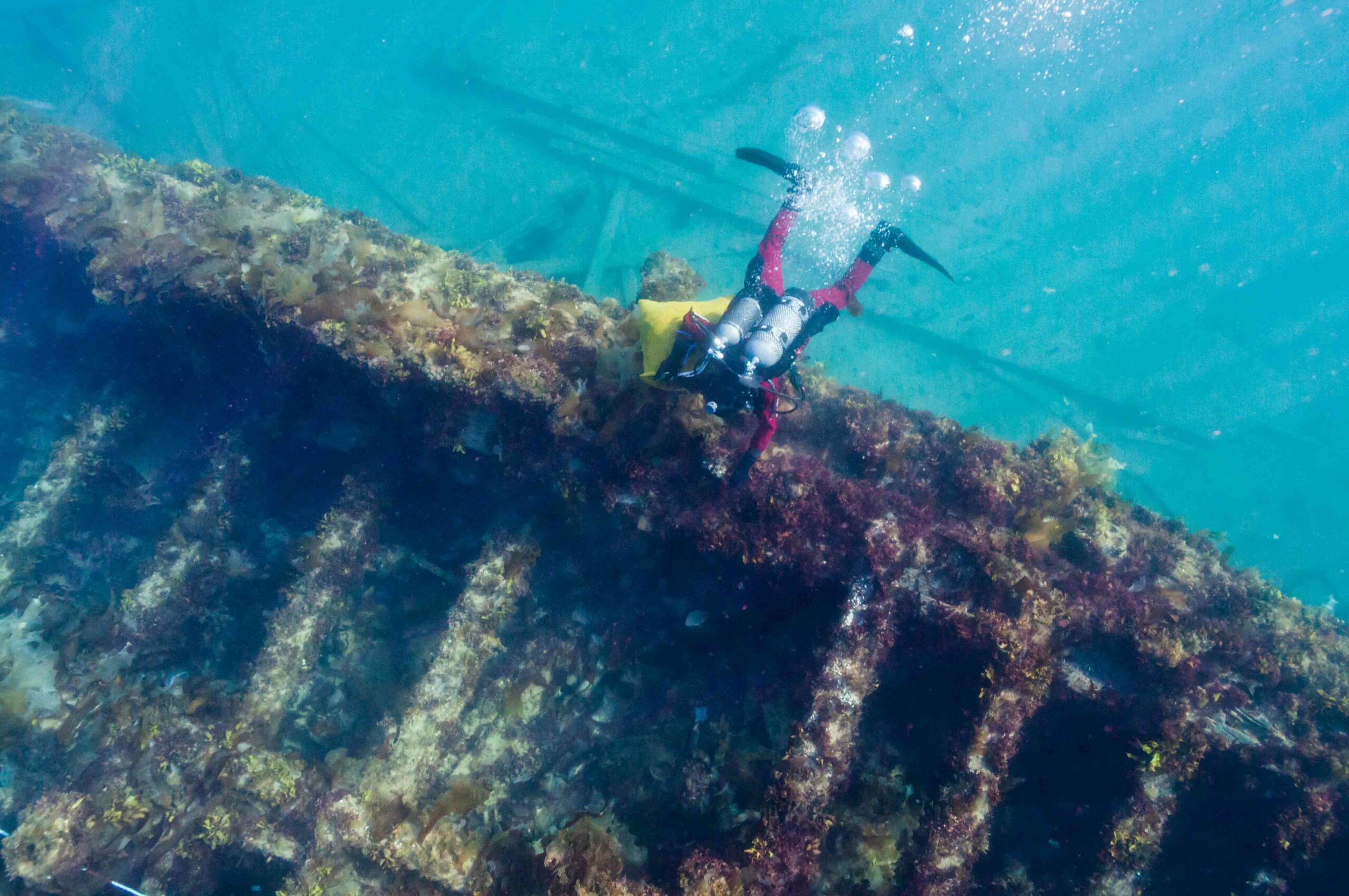

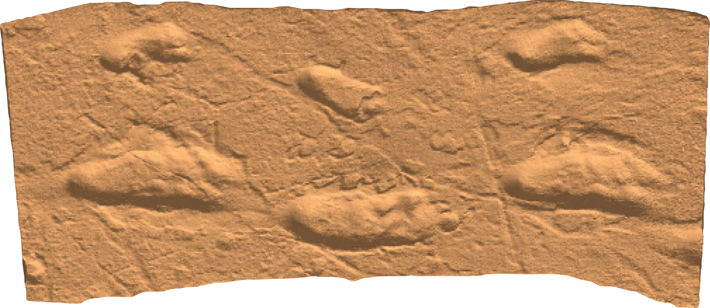

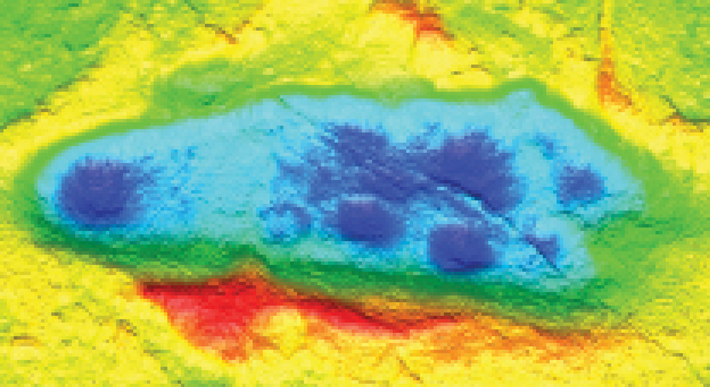

But now, a team at Bournemouth University in England has developed a software package called DigTrace and created a digital model of the footprints left by one of the other individuals. The team used the software, which is also being applied to modern crime scene analysis, to create 3-D scans of the overlapping footprints and isolate one set. They estimate that the individual who left these was around five feet tall, and walked at approximately the same pace as the individual who left the undisturbed prints. Team leader Matthew Bennett says that comparison of the two sets of footprints suggests that the feet of these individuals worked at a level of efficiency similar to that of modern humans. “This debate has raged for 40 years based on the gait of one individual representing an entire species,” Bennett adds. “Now, at least, we’re making the debate on the basis of two individuals.”