Outside the village of Brampton, Cambridgeshire, a handful of archaeologists huddle with a small group of local volunteers. Some of these professionals have been working here for two years and are all that remain of one of the largest archaeological teams ever assembled in Britain. They are in the final stages of excavating a small medieval hamlet called Houghton and have invited members of the public to join them for their final few weeks. Houghton was once a bustling little settlement, its dozen or so properties arranged around a broad central track. The scattered postholes and pits from this long-forgotten village are emblematic of the entire landscape, which has seen waves of people come and go over the past 6,000 years. Each has left an imprint upon the terrain.

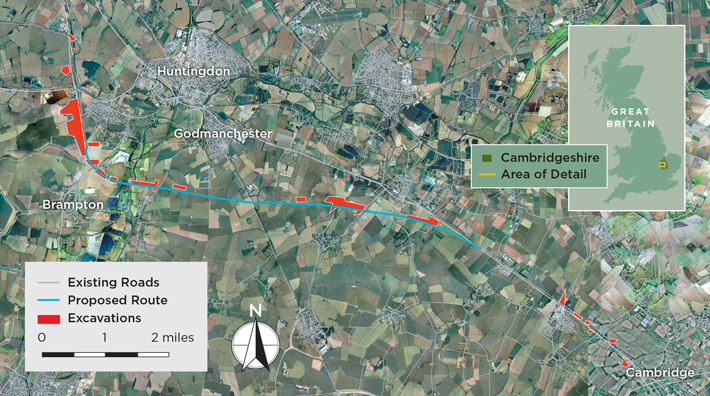

Dump trucks, bulldozers, and other heavy equipment rattle away behind the archaeologists, kicking up the dust that seems to perpetually hover above the mostly flat farmland that forms the backdrop to this once bucolic countryside. As it happens, the 800-year-old settlement is in the middle of a construction zone, a huge infrastructure project to upgrade and extend a 21-mile stretch of the A14 roadway between the towns of Cambridge and Huntingdon. Houghton is one of the final sites that must be cleared before the archaeologists’ work is complete and they surrender this tract of land to the advancing army of road builders.

England is so archaeologically rich that hardly any construction project takes place without encountering at least some evidence of its deep historical past. But, unlike what they encounter during most preconstruction or rescue excavations, here the archaeologists aren’t investigating a single site from a single time period, but dozens of sites spanning nearly the entirety of English history. According to Highways England’s Steve Sherlock, archaeology manager for the A14 excavations, the dig’s scale is unprecedented. “It’s the biggest road archaeological project in the country and the largest project of this nature that has ever been undertaken here,” he says.

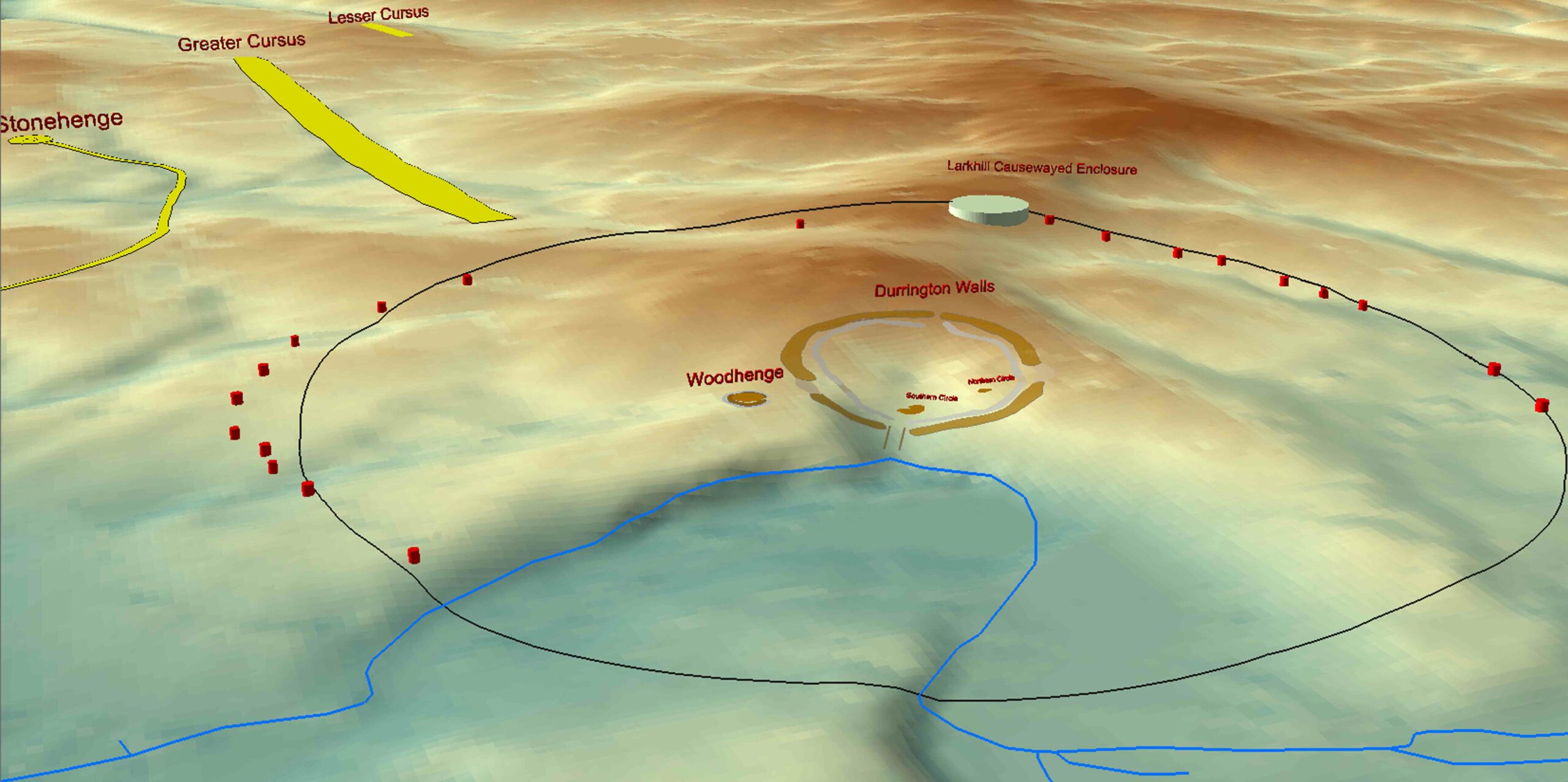

Since it would be nearly impossible to conduct fieldwork along all of the A14 construction corridor, archaeologists conducted intensive preliminary geophysical work, field assessments, and exploratory excavations that included an astounding 17 miles of test trenches to see where potential sites might be located. They finally homed in on a targeted area of 1.4 square miles to fully excavate, an expanse slightly larger than New York’s Central Park. Ultimately, this epic endeavor would require a team of more than 250 archaeologists.

England’s long history is marked by a series of transformative events. Some of these are hard to pinpoint, such as the adoption of bronze or iron technology. Others are more easily recognizable, such as the Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman invasions. All of this history played out on the Cambridgeshire countryside, creating a giant palimpsest that has been built upon, erased, and built upon again, over a millennia-long cycle. As the roadwork has slowly cut a swath through the county, it has become possible to imagine how the landscape might have looked at different periods, almost like turning the pages of a flipbook. “The preliminary work suggested there was a lot here,” Sherlock says, “but there have been tremendously exciting surprises along the way.”

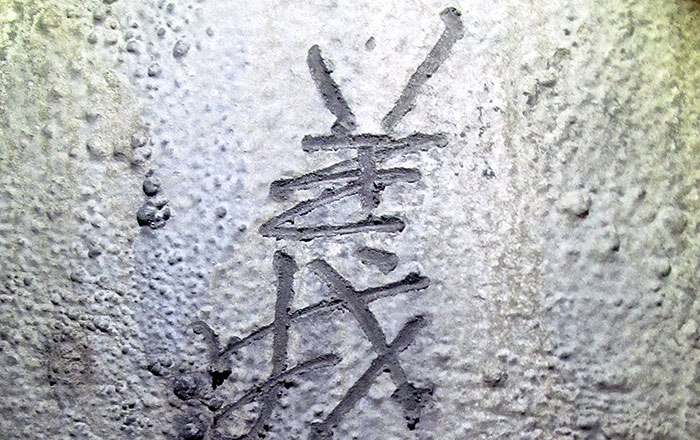

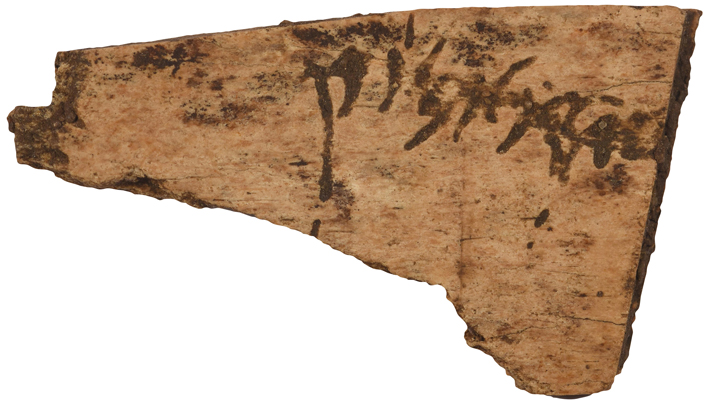

In all, the A14 team discovered three Neolithic henges, 300 burials in seven cemeteries, dozens of small Iron Age and Roman farmsteads, 40 Roman pottery kilns, three Anglo-Saxon villages, and the abandoned medieval hamlet of Houghton. They have amassed seven tons of pottery, five tons of animal bones, and 140 tons of environmental soil samples. Among the 8,000 excavated artifacts are Bronze Age stone tools, pieces of Iron Age weaving equipment, and, from the Roman era, copper brooches, jet jewelry, a soldier’s belt buckle, and even a fragment of a bone tablet with cursive Latin writing. Taken all together, it is an almost incomprehensibly large archaeological haul. “It’s kind of blown our minds,” says Emma Jeffery, senior archaeologist at MOLA Headland Infrastructure, a consortium formed by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) and the contract firm Headland Archaeology, which is responsible for the A14 project. “Our sense of scale, and everything else, has been completely warped by it all.”

One of the many questions the A14 archaeologists are investigating is why this particular strip of land attracted so many different groups of people over such a long period of time. The key draw may have been the natural trade and communication routes that crisscross the region, in particular the River Great Ouse, which snakes its way across the A14’s path, linking this inland area with the North Sea. “I think it has a lot to do with the transport networks,” says Jeffery. “You’ve got the Great Ouse, as well as other tracks and routes through the landscape that I think helped.” Sections of the new A14 partially follow the route of a Roman road that once connected the ancient towns of Godmanchester and Cambridge.

Sherlock suggests that the region’s geology may have been an even more important enticement to settlers. Much of Cambridgeshire is flat and its lower-lying areas are prone to flooding. But along the A14 corridor, there are pockets of land that contain gravel substrata, which drain more easily, and thus are more suitable for habitation. “The geology is fundamental, really,” explains Sherlock. “You could farm or raise livestock in the wetter areas, but people always chose the places where there are gravels and thus drier land to live on.”

When archaeologists began clearing the A14’s proposed route, it became readily apparent that the Roman imprint on the area was profound—but this was to be expected. The emperor Claudius invaded Britain in the mid-first century A.D., and for the next 400 years, until the end of the empire, the Romans radically transformed the island by building roads, towns, and military outposts as part of an all-encompassing imperial administrative system. Finding the Romans anywhere in Britain is not difficult, especially when digging along the course of a Roman road. But, given the extent of the excavations, researchers now have a much more complete view of how this area was organized during the period.

Travelers following that Roman road from Cambridge to Godmanchester during the first few centuries A.D. would have recognized the telltale signs of the Roman economic, industrial, and administrative machine at work. Along the journey, they would have seen large villas and small farms scattered across the landscape, as well as an agricultural supply depot with an artificial pond. A network of small trackways linked the depot to outlying satellite farms. Closer to Huntingdon, near the western banks of the Great Ouse, they might have passed one of the dozens of Roman pottery kilns, evidence of the area’s ceramics industry, which was enabled by the river’s abundant clay deposits. According to Sherlock, the area had all the necessary resources to support a booming pottery trade. “You’ve got your clay, you’ve got your Roman road, you’ve got the Great Ouse, and you have Godmanchester,” he says. “The material, the transport links, and the demand are all together.”

As archaeologists moved across the landscape over the past two years, they also exposed an unexpected history more than 4,000 years older than the Romans. Sherlock and his team now know that the earliest evidence of human occupation in this part of Cambridgeshire dates to the Neolithic period (4000–2500 B.C.), one of the most revolutionary eras in England’s history. As farming became widespread for the first time, forests began to disappear. People all across Britain began to construct the island’s first large-scale monuments—A14 archaeologists have discovered three circular earthen henges, the largest of which measures 165 feet across. Most scholars believe that this type of henge was used for ritual gatherings and ceremonies, suggesting that this area may have had sacred meaning to those who lived here as long as 6,000 years ago. Even though the sacred connotations these enigmatic enclosures once possessed may not have carried over to subsequent eras, they continued to be respected landmarks. “These monuments survived as large physical features from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age, through the Roman era, and were still visible in the Anglo-Saxon period,” says Sherlock. Buildings that were constructed centuries, or even millennia, later seem to have been carefully arranged around the henges, as if not to disturb them. “They were probably still being used in some sort of way, maybe as a place that at certain times of the year you would come and meet and celebrate,” Sherlock adds.

For the next 4,000 years, technological advances marked the advent of new epochs, including the Bronze Age (2500–800 B.C.) and the Iron Age (800 B.C.– A.D. 43). During these periods, too, Cambridgeshire’s inhabitants reshaped their landscape. The A14 archaeologists have found Bronze Age fields demarcated by large ditches that served as territorial boundaries. The researchers have also unearthed a large Bronze Age funerary barrow containing 65 burials near the Great Ouse. Another barrow, containing 50 more burials, was identified a few miles away. In total, 150 Bronze Age human burials have been found scattered throughout the project’s purview.

The team has located as many as 15 farmsteads and settlement sites dating to the Iron Age. Among these, they have unearthed evidence of daily life, including weaving combs, loom weights, agricultural tools, and coins. Microscopic soil analysis has indicated that Iron Age farmers were cultivating spelt and barley in the surrounding fields. And there is even evidence, in the form of charred and fermented grains, that the farmers were brewing beer, the earliest indication of this practice in Britain.

While the discoveries of sites dating to the Neolithic, Bronze, Iron, and Roman Ages were exciting, as they helped reimagine the first 4,500 years of human history here, archaeologists were perhaps most surprised by the evidence of post-Roman life in this part of Cambridgeshire. After the collapse of Roman Britain in the mid-fifth century A.D., a new era was ushered in when groups of Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from northern Europe invaded the island. Once again, the English landscape was transformed as many Roman settlements and institutions, and even elements of the remaining infrastructure broke down and were abandoned. Very little is known about this period in Cambridgeshire because there is a paucity of archaeological evidence, but the A14 construction is beginning to change that. “Across the whole project the Saxon discoveries were the most remarkable of all,” Jeffery says. “We expected the Roman settlements, the Iron Age settlements, and everything else, because they have been found elsewhere across Cambridgeshire. We have known about them through geophysics and crop marks. But the number of Saxon buildings, and the intensity of Saxon activity, really was unexpected.”

One of the reasons Anglo-Saxon settlements are rarely excavated is that many of them have been continuously occupied, and remain so today, rendering them inaccessible. “We might find a couple of buildings if we are lucky,” explains Jeffery, “but we don’t get them too often because they are under modern villages and we just can’t reach them.” Even when Anglo-Saxon sites are located in more rural areas, they can be difficult to identify. Since they were predominantly constructed of timber and other perishable materials, Anglo-Saxon buildings leave very little archaeological signature once they are abandoned and the materials decompose. “The problem with these structures is that they don’t necessarily show up in the geophysics because what remains of them is so small,” Sherlock says. “Ephemeral things, such as a line of postholes, may not appear in a magnetometer survey, so you don’t find them until you strip large areas.”

Stripping large areas is precisely what the A14 roadwork entails. As a result, at least three Anglo-Saxon settlements dating to between the fifth and tenth centuries have been revealed. The largest once had as many as 50 buildings, including houses and workshops spread across 15 acres. It is one of the biggest sites of its kind ever found in the region. The Anglo-Saxon period in Britain is often referred to as the Dark Ages because it is perceived to have lacked culture, especially when compared to the preceding Roman period. But for Sherlock, some of the new evidence tells a much different tale. For example, a finely crafted Anglo-Saxon bone flute–like musical instrument, one of only about 30 that have ever been found in Europe, speaks to a more refined population. “These weren’t primitive people living here,” says Sherlock. “They were literate and had music and art.”

Directly adjacent to one of the newly uncovered Anglo-Saxon sites is the abandoned medieval village of Houghton. Although the town’s name appears on old maps, no physical traces of its existence had previously been found. Since it is not directly in the path of the roadway, and all other essential work had been completed, archaeologists were allowed to investigate the site at a less hurried pace.

The abandonment of towns and villages in England during the medieval period was not uncommon, especially in the late fourteenth century when the Black Plague ravaged the country, killing as much as 60 percent of the population. Yet Houghton was deserted decades before the plague’s arrival. “We were particularly excited because it’s a slightly earlier village, so it’s not like the deserted medieval villages that you find elsewhere,” Jeffery says. She has learned that the fate of Houghton’s residents was determined by a particular set of circumstances. They were not, in fact, victims of disease but, instead, of cruel medieval politics.

The village’s only road, which excavators have dubbed “Houghton Lane,” ran through its center and connected villagers to a wooded area known as Brampton Wood. Brampton Wood was vital to Houghton’s residents. “The villagers would have used the forest for food, for fuel, and for other resources,” says Jeffery. But sometime after Henry II (r. 1154–1189) ascended the throne of England, the king claimed the whole county of Huntingdonshire, of which Brampton Wood was part, as his exclusive hunting grounds. This essentially prohibited Houghton’s villagers from accessing and using the forest upon which they had become dependent. “At that point the woods were basically fenced off, so people lost their economic viability,” Jeffery says. Suddenly barred from the land that had sustained them, the villagers had no choice but to pack up and move elsewhere.

Although the team has uncovered most of the village’s footprint, there does not appear to have been a church or even a manor house. This may indicate that there were no church officials or local nobles who might have been able to speak up on the villagers’ behalf and resist the crown’s declaration. “There was nobody here to say, ‘No, I’m not giving you this bit of land,’” Sherlock says. “It’s just a small hamlet, so the king could dispossess the people a lot more easily and move them on.”

The A14 excavations have elucidated the ebb and flow of thousands of years of settlement in this small stretch of southeastern England. They have shown that people have come and gone, whether through natural circumstances, because another group usurped their territory, or because they were forced from their land by the sovereign. Soon, all traces of this massive archaeological undertaking will be gone—artifacts, monuments, houses, tombs, streets, and entire settlements will have been removed from the ground, reburied, or paved over. In the coming months and years, millions of people will speed through this countryside along the newly built A14, most of them likely oblivious to the 6,000 years of human history just outside their car windows.