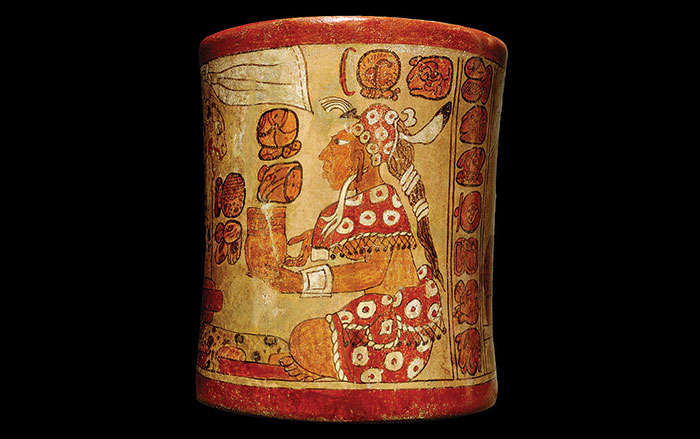

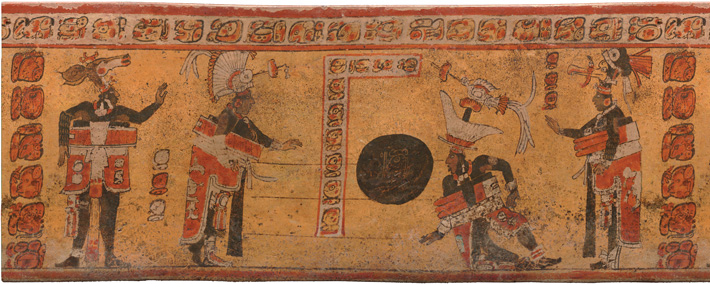

In Classic Maya society, the head was the center of a person’s identity and the animating force that defined them. Thus, there is great variety in Classic Maya headdresses, as different roles, occupations, and ceremonies required distinct sets of headgear. Ballplayers and warriors, for example, are both depicted wearing elaborate animal headdresses. It is possible the Maya thought that adorning oneself with a particular animal head allowed the wearer to take on some of that animal’s characteristics. The animal someone wore may also have correlated with their rank. A Late Classic (A.D. 600–900) vase from the Peten region of Guatemala shows a ball game believed to have been contested between representatives of the cities El Pajaral and Motul de San Jose. The kings’ plumed headdresses are topped with hummingbirds, while their auxiliaries wear a comically depicted deer and vulture, respectively. In a Late Classic mural at Bonampak in Chiapas that illustrates the aftermath of a great battle, the most important participants wear jaguar headdresses.

Maya kings and queens are typically shown wearing flamboyant headdresses bedecked with masks, quetzal feathers, and jewels as they conjure their ancestors or perform other important rites. However, the most significant element in a ruler’s headdress was among its simplest. “A bark-paper headband adorned with a diadem of jade or shell was bound to the heads of rulers the day they acceded to the throne,” says anthropologist Alyce de Carteret of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. This simple white headband was the signature attire of Huun Ajaw, one of the mythical Maya Hero Twins. The pair is described in the Popol Vuh, the epic of the K’iche’ Maya of Guatemala, as having defeated a range of monsters and evil gods, allowing for the rebirth of their father, the Maize God. The diadem on these headbands often took a form scholars have named the “jester god,” after the resemblance of its three-pointed head to the cap of a medieval jester. This god appears to have had its roots in representations of the maize plant. Maize was the foundational staple of the Maya diet and, according to the creation story told in the Popol Vuh, the substance from which the gods formed early Maya ancestors. Thus, it came to be seen as a symbol of royal authority. “We know that headdresses were immensely potent items, perhaps best exemplified by the exception that proves the rule,” de Carteret says. “Captives are often shown nude, their disheveled hair falling to their shoulders. It’s the ultimate expression of shame. Without a headdress, they are without power or protection.”